Patients with operable renal cell carcinoma must continue to be followed after nephrectomy. According to a study from the renowned Mayo Clinic in Rochester, the necessary duration of follow-up after nephrectomy can be determined adequately and individually with the help of a risk model [1]. The question is: At what point does the risk of death elsewhere (unrelated to renal cell carcinoma) exceed the risk of recurrence? The researchers investigated this using the parameters of age, tumor stage, recurrence site, and comorbidity. There were surprising differences within the patient groups. Another study presented at the 67th Congress of the DGU was dedicated to the prognostic differentiation of patients with stage pT3 renal cell carcinoma [2].

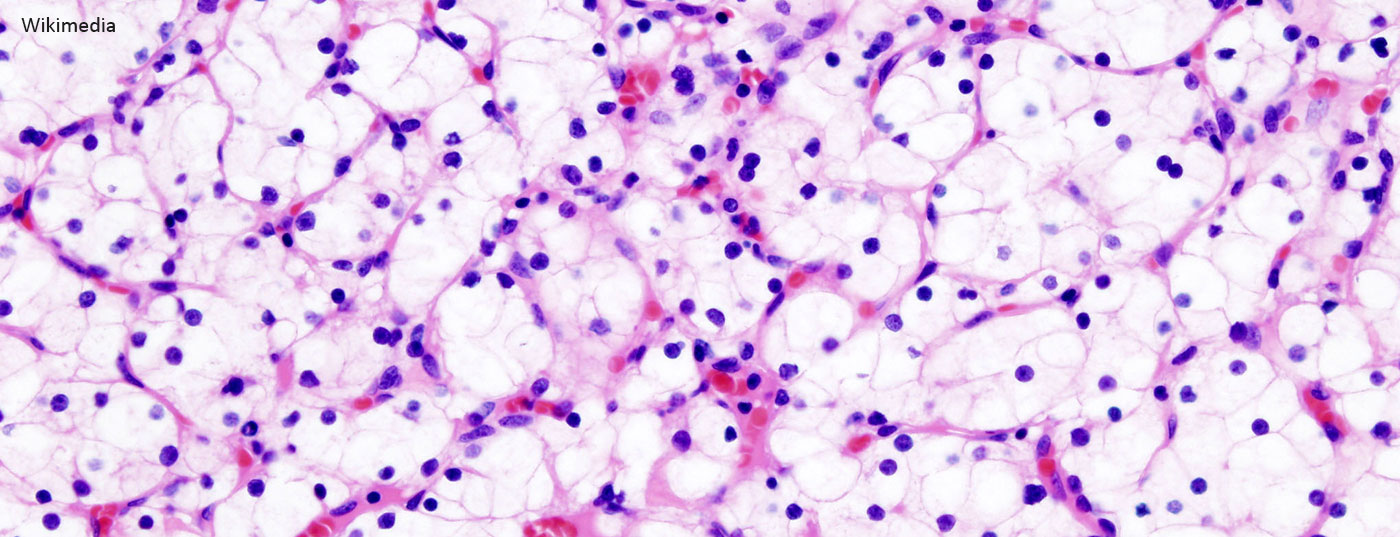

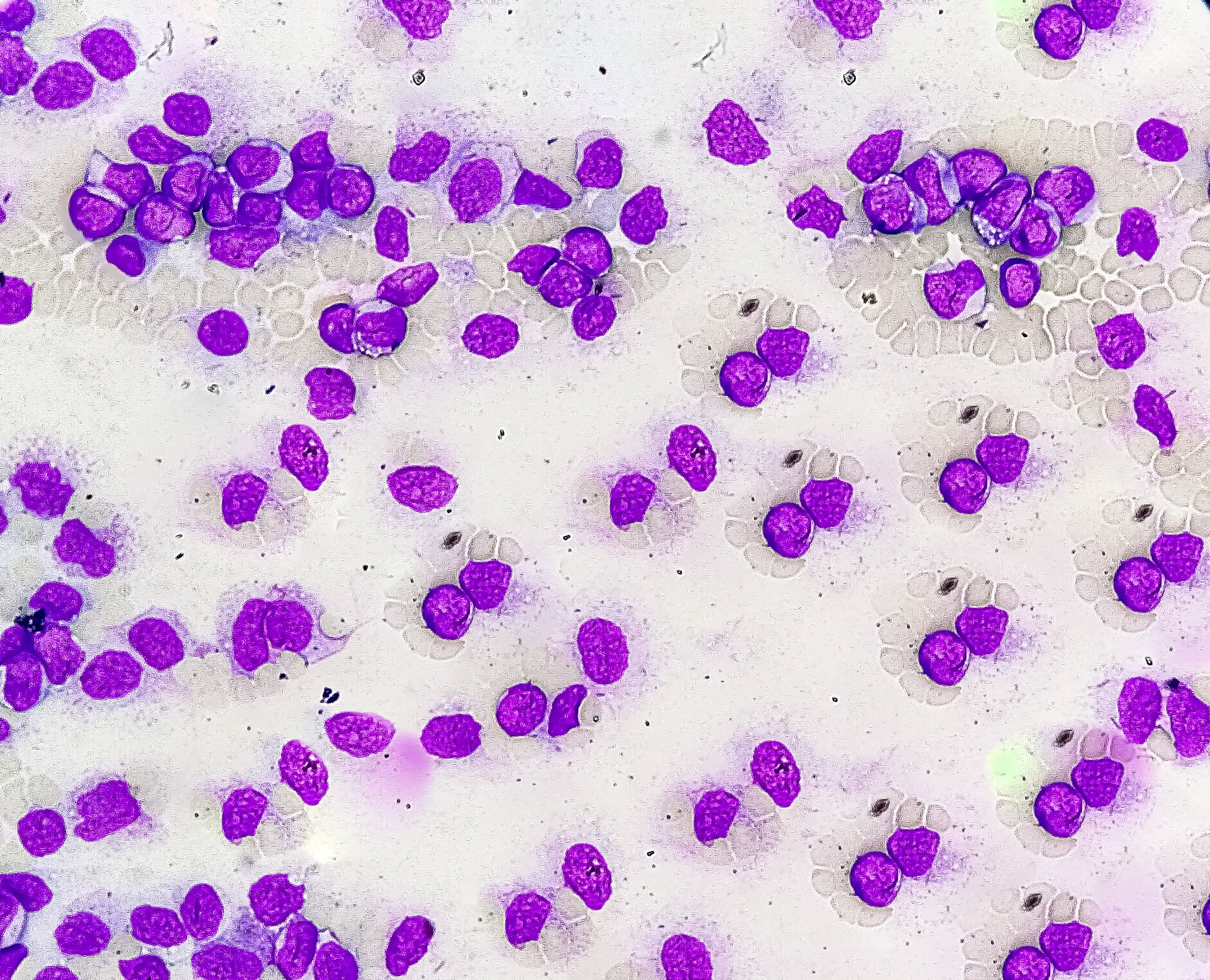

The standard therapy for renal cell carcinoma is nephrectomy with complete surgical removal of the tumor tissue. However, after surgery, recurrence is imminent, which is why follow-up care is crucial.

Generally, the first two to three years after surgery are considered critical, as most recurrences occur during this period. However, the appropriate duration of follow-up after radical or partial nephrectomy remains unclear, with a lack of evidence to support current recommendations and guidelines.

Risk for recurrence and death

A study published in September in the Journal of Clinical Oncology takes a new, risk-adjusted approach in this regard: it contrasts the risk of recurrence with the risk of death elsewhere.

The interplay of various risk factors indicates at what point the risk of other death exceeds that of developing a recurrence. Up to this point, the benefits of follow-up justify the resources devoted to it by the medical system, and thus the optimal duration of follow-up could be set here.

After that, other health factors of the patient exert a greater influence on survival than the renal cell carcinoma, and thus follow-up that is “only” limited to this tumor would from then on always fall short and no longer be worth its cost. Of course, ethical aspects are left out of such considerations, since they are based exclusively on statistical values.

Large differences regarding optimal duration

Patients were stratified by age, tumor stage, recurrence site, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, the likelihood of dying from a comorbidity in the next few years.

In total, they used data from 2511 people with M0 renal cell carcinoma who had undergone surgery between 1990 and 2008. After a median follow-up of nine years, 676 of the patients developed a recurrence. There were significant differences in the risk model. A weighty factor – as is so often the case – was age:

- Patients younger than 50 years with stage pT1Nx-0 carcinoma and a score on the CCI of ≤1 had a higher risk of recurrence (abdominal) than other death for an average of more than 20 years after surgery. Only then did the risk of death not associated with renal cell carcinoma exceed that of recurrence. It is therefore possible that follow-up care would have to be extended to a longer period than is usual today.

- In contrast, patients aged 80 years or older with stage pT1Nx-0 carcinoma and a score on the CCI of ≤1, on average, had a higher risk of recurrence than other death only up to six months after surgery. Thereafter, the risk of death not associated with renal cell carcinoma already exceeded that of recurrence. From this point on, the benefit of routine follow-up would no longer statistically justify the effort and cost to the medical system. Other health factors are now more likely to demand attention.

- Almost self-explanatory, an increasing value on the CCI also rapidly shortened the time span: in patients with a tumor pT1Nx-0 but a CCI of ≥2, the other risk of death exceeded the risk of recurrence in the abdomen as early as 30 days after surgery – and remarkably, this was independent of patient age. So perhaps no routine follow-up is indicated in this group at all?

What now?

No definitive conclusions can be drawn from the study, but it does provide food for thought. The data show that certain patients require longer follow-up than is allowed by the guidelines. For others, however, a shorter period is justified – at least statistically. Nevertheless, clinical judgment and experience in dealing with individual patients must remain mainstays of decision making, as the authors also repeatedly emphasize. Compared with past practice, however, their approach can at least provide a more stable basis on which to base clinical decisions. So the discussion about the optimal duration of follow-up care will not die down anytime soon.

Prognostic differentiation with the TNM classification

A retrospective study presented at the 67th Congress of the DGU [2] took a critical look at two items from the seventh edition of the TNM classification:

In substage pT3a, the two factors perirenal fat infiltration (PFI) and renal vein invasion (RVI) are combined, although it is unclear whether their prognostic impact is actually comparable.

Furthermore, the prognostic discriminability of stages pT3a and pT1-pT2 is controversial.

Using 7384 patients with stage pT1-pT3a renal cell carcinoma who had undergone (radical or partial) nephrectomy between 1992 and 2010, the researchers addressed the following question: do patients with PFI alone actually have comparable cancer-specific mortality to patients with RVI±PFI?

In multivariate analysis that accounted for age, sex, surgical method, subtype, tumor size, Fuhrman grading, and nodal status, it was found that both patients with PFI alone (HR 1.94) and those with RVI±PFI (2.12) had a significantly higher mortality risk than patients in stage pT1-2. Thus, both factors (PFI and RVI) are independent prognostic factors for cancer-specific mortality.

Again, comparing PFI patients with RVI±PFI patients, there are no significant differences in mortality risk (HR 1.17; 95% CI 0.86-1.61; p=0.316). Therefore, combining PFI and RVI into one staging category seems justified. Both factors have a comparable prognostic impact and both contribute independently to an increase in risk.

Subsumption of pT2 and pT3a tumors ≤7 cm.

Regarding the second criticism, the investigators conclude that patients with pT2 and those with pT3a tumors ≤7 cm (with PFI and/or RVI) have a great prognostic proximity, which would justify their association in one staging category. Therefore, based on the study, the authors propose an alternative staging system: Subsummation of pT2 tumors of any size and pT3a tumors ≤7 cm. Thus, in contrast to the current TNM classification, all stages could be prognostically distinguished without any overlap of the 95% confidence intervals.

Literature:

- Stewart-Merrill SB, et al: Oncologic Surveillance After Surgical Resection for Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Novel Risk-Based Approach. JCO September 8, 2015. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.8009 [Epub ahead of print].

- Brookman-May S: Renal cell carcinoma – analysis of the CORONA database: the 5 main conclusions. Congress newspaper for the 67th Congress of the DGU 2015.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(9-10): 2-3.