The current diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) allow a very early and specific diagnosis in most cases. When MS is suspected, however, it is always important to consider the most common differential diagnoses and to rule out “mimicks.” The diagnosis of MS-like clinical pictures has therapeutic and, of course, prognostic consequences. If doubts about the diagnosis of MS arise during the course of the disease, there should be no hesitation in renewing differential diagnostic validation.

To date, there are no biological markers for the definitive diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS). No clinical neurological symptom is pathognomonic, as MS foci can occur anywhere in the CNS. The average time that elapses between the often unrecognized initial symptom and the diagnosis is still about two years [1]. As the most common neurological disease of young adulthood, it can cause early disability and threatens premature retirement. In view of the pathophysiological findings and the early start of therapy required today, this is a loss of time that can no longer be made up.

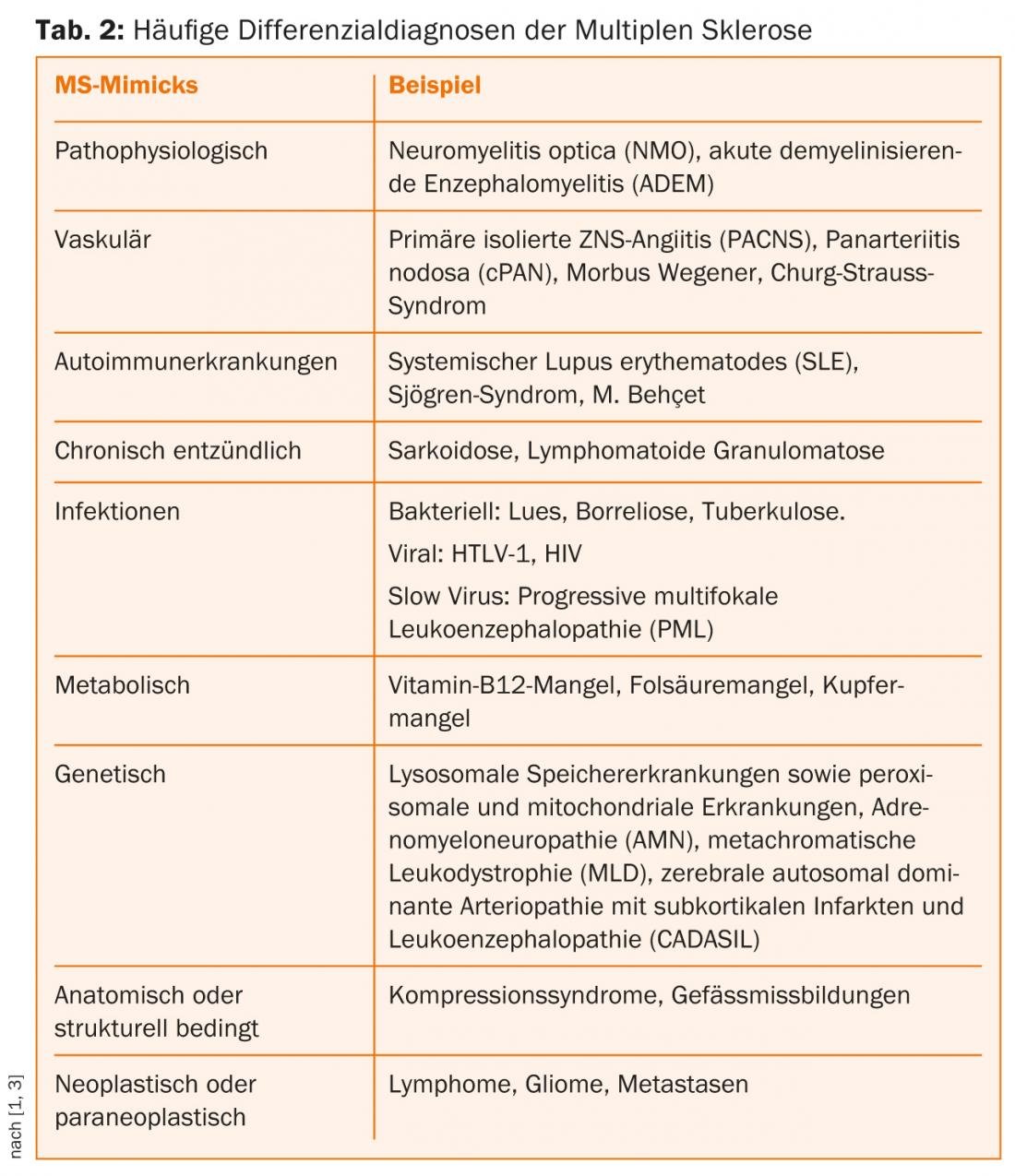

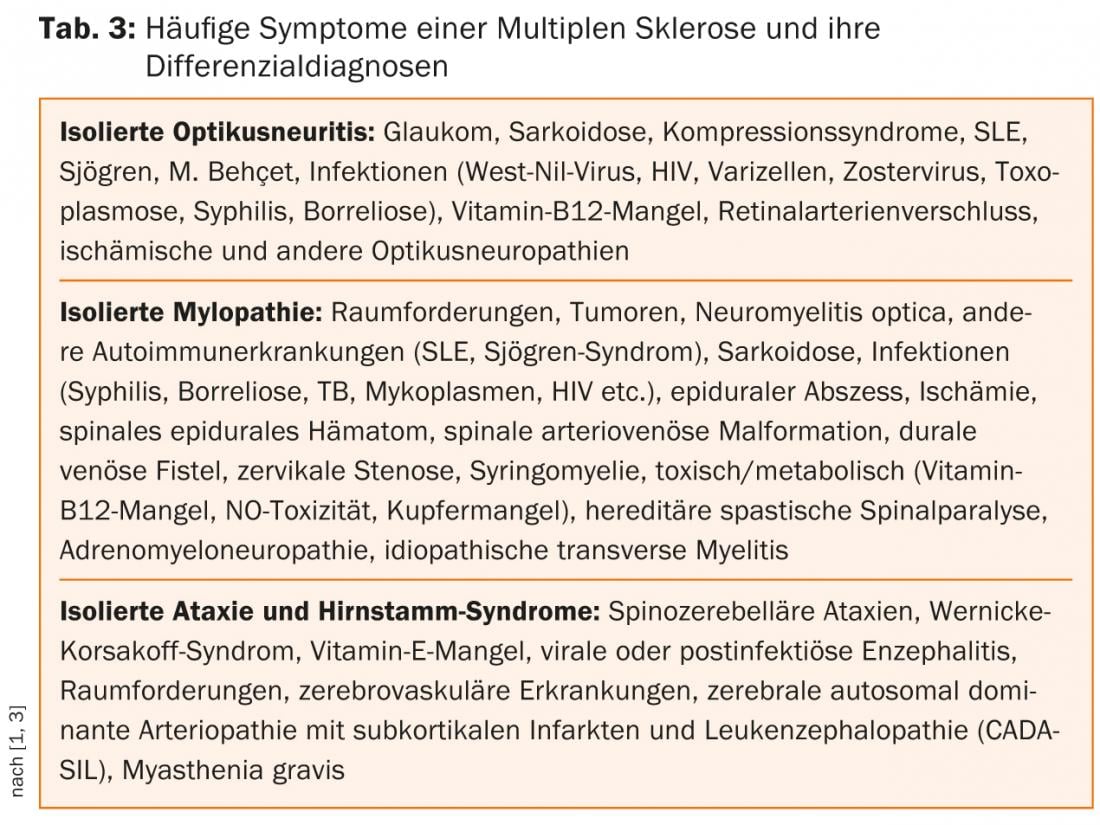

The second revision of the McDonald criteria allows the diagnosis of MS at the first episode and with single-session MRI, but still only with the most careful exclusion of other possible differential diagnoses (Tables 1 and 2) [2–5].

In the sense of a procedure according to the principle “frequently diagnose common”, the differential diagnoses (DD) that are possible in our latitudes and in the “typical”, i.e. younger patient with suspected MS, will be dealt with cursorily in the following.

Age and medical history

The age distribution of MS shows a peak of disease around the age of 30. MS in children and adolescents and first disease beyond the age of 45 are less common. However, there are well-documented individual cases of MS that first manifested in the first decade of life, as well as those that manifested in the seventh decade.

Obtaining an accurate history is essential and is often sufficient to establish a tentative diagnosis of MS. The history should include questions about any past episodes of neurologic deficits that may provide clues to past relapses and may have been previously misinterpreted. The question of other autoimmune diseases in the patient himself or in family members is also important. Questions about complaints and symptoms related to bladder, rectal, and sexual function are important. Hidden symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating and depression, and pain should also be sought (autonomic dysfunction) [3–5]. Common early symptoms of MS include:

- Sensory disturbances such as formication, furry feeling, tingling (>30%)

- Visual disturbances with blurred, foggy, or nebulous vision due to unilateral optic neuritis (about 16%)

- Gait disturbances with frequent load-dependent weakness of the legs and gait unsteadiness (approx. 5%).

Other symptoms include: Vertigo (30-50% of cases), nystagmus (2-4%), intention tremor, bladder and bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, double vision, facial paresthesias, trigeminal neuralgia, ataxia, dysarthria, fatigue (especially at relapse), sleep disturbance, depression, euphoria, cognitive impairment (34-65%), dementia (5%), cerebral seizures (2-3%), and positive Lhermitte’s sign.

Differential diagnosis of MS

The richness of forms of the symptoms of MS makes their differential diagnosis against a whole range of cerebrospinal affections so difficult. Other chronic inflammatory, metabolic, vascular, neoplastic, and/or pathogen-mediated diseases may present with similar symptoms (Table 2) [3–5].

Pathophysiology Mimicks

MS is an immune-mediated chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system that histopathologically results in varying degrees of axonal damage and demyelination. There are a number of other autoimmune diseases involving the central nervous system that are difficult to distinguish from MS because of the variety of symptoms.

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is also an immune-mediated, chronic inflammatory disease of the CNS. “NMO spectrum disorders” (NMOSD) include isolated longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis (LETM), monophasic or recurrent isolated optic neuritis, and distinct forms of brainstem encephalitis. NMO shows a clear preference for the female sex (depending on the cohort up to 9:1) and manifests on average about ten years later (4th decade of life) than MS. Based on the detection of aquaporin-4 antibodies (AQP4-Ak) directed against water channels expressed on astrocytes, NMO was classified in the so-called B-cell mediated autoimmune diseases. Serologic detection of AQP4-Ak and predominantly lymphocytic cell count elevations of >20 to 50 µl in CSF are not uncommon in NMO during an acute episode. In addition, positive oligoclonal bands are found in only about 15-30% of NMO patients. Compared to MS, relapses in NMO are often more severe and lead more rapidly to permanent disability due to usually only incomplete remission [5].

Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and its maximal variant, acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (AHLE), are rare, inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the CNS. Unlike MS, ADEM is more common in childhood than in adults and occurs predominantly in close temporal association with infections or vaccinations. Clearly defined diagnostic criteria for ADEM do not exist. The rare adult cases are a challenge [5].

Angiitis and collagenosis

Primary isolated CNS angiitis (PACNS) is a very rare autoimmune disease characterized by inflammatory damage to small and medium caliber cerebral vessels. It can be considered as a differential diagnosis in the presence of multifocal or diffuse CNS symptoms with a progressive or relapsing-remitting course. MRI and digital subtraction angiography provide clues. If vasculitic changes are present outside the CNS, PACNS is excluded [5].

Systemic (primary) vasculitides are classified according to the size of the affected vessels and their histologic findings. Panarteritis nodosa (cPAN), Wegener’s disease, and Churg-Strauss syndrome are possible differential diagnoses of MS. They are characterized by granulomatous and necrotizing inflammation of the small vessels and the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANCAs).

Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, or Behçet ‘s disease can rarely cause neurologic symptoms due to vasculitis. In principle, in all chronic inflammatory autoimmune diseases, hemorrhages and ischemic infarcts in the supply area of the affected vascular territories can complicate the course and lead to severe neurological symptoms in the PNS and CNS (secondary vasculitides).

Behçet ‘s disease is a systemic vasculitis and predominantly affects men from the Mediterranean region. The peak of the disease is beyond the third decade of life, rarely the first manifestation occurs in adolescence. A strikingly frequent association with the HLA-B51 antigen is found in affected individuals. Recurrent oral and genital ulcerations and skin changes in the form of sterile pustulopapular efflorescences and erythema nodosum are typical. Eye involvement is typical. Rarely, a parenchymal CNS manifestation (meningoencephalitis) occurs, affecting the brainstem in approximately 50% of cases. The neurological appearance varies depending on the affected brain area or vascular structures and can be either relapsing or chronic progressive. Neuro-Behçet is detected by MRI and CSF diagnosis [5].

Infestation of the CNS alone in granulomatous diseases such as neurosarcoidosis is extremely rare; co-infestation is found in approximately 5% of sarcoidosis patients. In CNS manifestations, mostly unilateral cranial nerve involvement (facial nerve, optic nerve, acoustic nerve) is the most common initial event. The further clinical appearance depends mainly on the localization and extent of the granulomas in the CNS.

Infectious causes

Whereas neurolues was the most common DD of MS in 1925, it is now rare, and new infectious causes are more important. Neurologic symptoms of lues caused by Treponema pallidum may present as early viral meningitis (stage 2), lues cerebrospinalis with concomitant cerebral arteritis (stage 3) and progressive paralysis/tabes dorsalis (stage 4) make an appearance. Especially in stage 3, the symptoms vary greatly. Demyelination foci in the brain and spinal cord characterize the stage of tabes dorsalis [5].

Differentially, neuroborreliosis should be considered especially in regions with a high infestation rate of ticks with Borrelia burgdorferi, even though its frequency in people infected with Borrelia is low at 0.3-1.4%. Three stages are distinguished, with stage 1, local erythema migrans, not yet showing neurological symptoms. If left untreated, disseminated infection (stage 2) may develop after weeks to months, involving various organ systems and thus also the CNS and PNS. Acute neuroborreliosis is characterized by segmental, often analgesic-resistant radicular pain without meningeal signs of irritation. In the course of the disease, more than 50% of the patients develop sensory irritations, paresis of the extremities and cranial nerve deficits (facial nerve, abducens nerve). After months to years, symptoms may develop in the sense of chronic progressive neuroborreliosis (stage 3: myelitis, myositis, vasculitis and polyneuropathy). MRI plays a minor role in neuroborreliosis; evidence of inflammatory CSF changes as well as intrathecal Borrelia-specific antibody production is conclusive in this case.

Among viruses, human T-cell leukemia virus 1 (HTLV-1), a human pathogenic retrovirus that predominantly infects CD4+ T cells and in very rare cases causes T-cell leukemia and/or leads to neurologic symptoms. Tropical spastic paraparesis is a very rare disease in our latitudes, with a mainly spinal course. HIV infection can also cause encephalomyelitis in its advanced stages.

Metabolic causes

Funicular myelosis is a vitamin B12 deficiency disease that leads to demyelination of the hindbrain, cerebellar side-strands, and pyramidal tracts, especially in the cervical and thoracic medulla. Similar to vitamin B12 deficiency, disorders of folic acid metabolism can result in a wide range of symptoms in varying degrees of severity. Neurological disorders include seizures, developmental delays, and myelopathic symptoms similar to those of funicular myelosis. Vitamin deficiency diseases are rare in our latitudes (alcohol, malnutrition). Vitamin utilization disorders due to genetic diseases are even rarer.

Genetic causes

In rare cases, monogenic diseases may also share phenotypic similarities with the clinical manifestation of MS. These inherited conditions include lysosomal storage diseases and peroxisomal and mitochondrial diseases such as Leber’s optic atrophy. Since in most cases clinical-neurological manifestations already occur in infancy and childhood, neuropediatricians are required.

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is a peroxisomal storage disease characterized by impaired degradation of overlong-chain fatty acids. It also usually begins in childhood, but there is also a very rare adult form, adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN: spastic paraparesis, adrenal insufficiency).

In the adult form of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD), one of the 30 different lysosomal storage diseases, spastic gait disorders, incontinence, and, more rarely, optic atrophy and eye movement disorders may occur in addition to common neuropsychological symptoms. The decisive factor in the clinical differentiation from MS in MLD is the involvement of the peripheral nervous system in the form of a mostly symmetrical, distally emphasized sensorimotor polyneuropathy.

Paraneoplasias and neoplasias

Patients with neurological symptoms often have a great fear of suffering from a brain or spinal cord tumor or metastases. A relapsing course with regression tendencies speaks against it. Headache, morning sickness, vomiting, changes in demeanor, slowing, and epileptic seizures can occur with both malignant and benign intracranial space-occupying lesions, but are rare in MS.

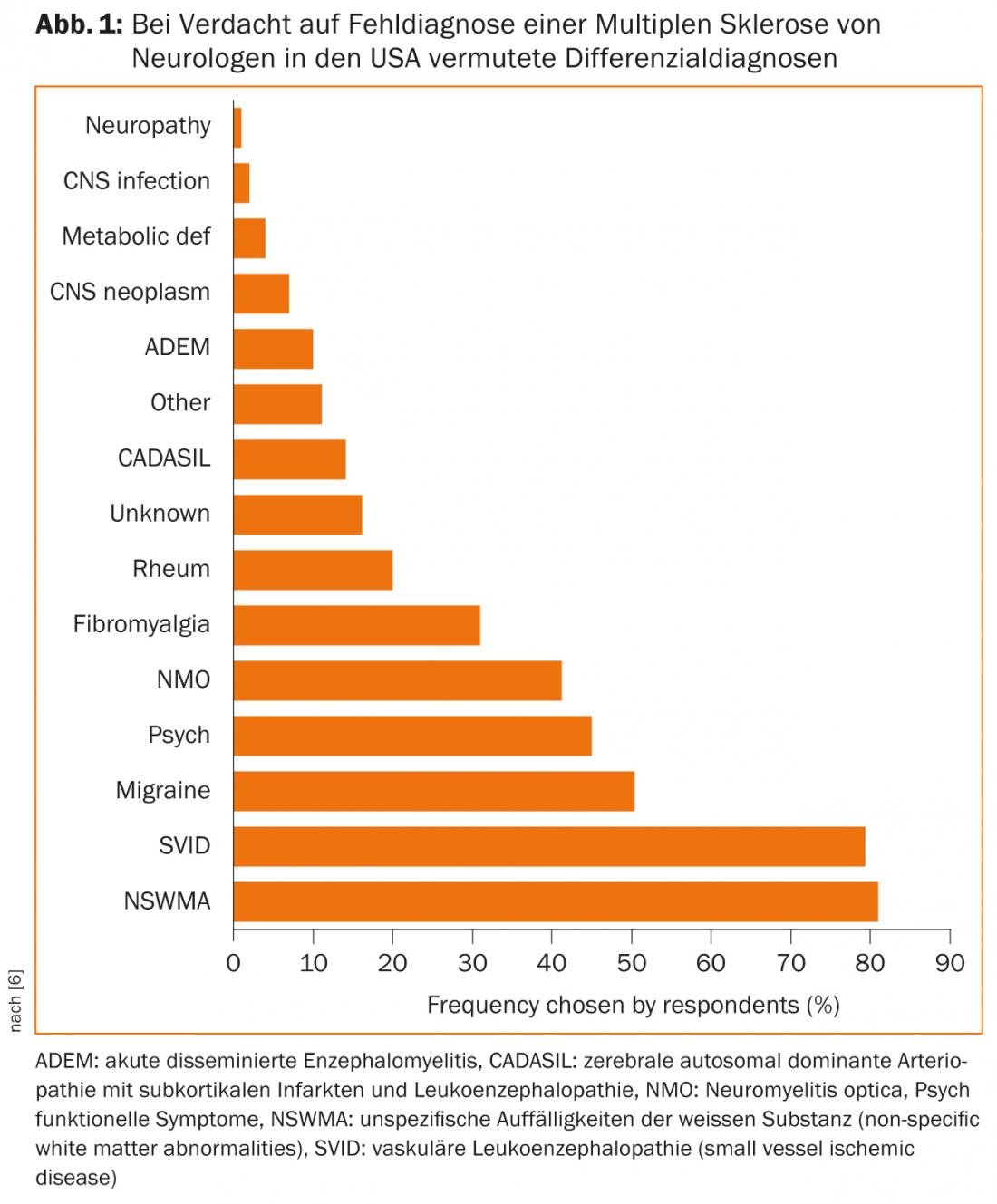

Suspicion of a misdiagnosis?

In cases with an atypical course, lack of response to current therapeutic options, or fulminant symptoms, it is imperative to revisit the differential diagnosis and consult with experts from other disciplines such as rheumatologists and infectiologists, if necessary. A survey of American neurologists shows which DD are frequently suspected when a misdiagnosis is made (Fig. 1) [6].

Prof. Dr. med. Adam Czaplinski

Literature:

- Fernández O, et al: Characteristics of multiple sclerosis at onset and delay of diagnosis and treatment in Spain (the Novo Study). J Neurol 2010; 257(9): 1500-1507.

- Polman CH, et al: Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011; 69: 292-302.

- Marcus JF, et al: Updates on Clinically Isolated Syndrome and Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Sclerosis. Neurohospitalist 2013; 3(2): 65-80.

- www.awmf.de: Multiple Sclerosis Guideline of the DGN AWMF Register Number: 030/050.

- Décard BF, et al: Differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) – MS mimics. Act Neurol 2012; 39: 83-99.

- Solomon AJ, et al: Undiagnosing MS: The challenge of misdiagnosis in MS. Neurology 2012; 78; 1986-1991.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2013; 11(6).