If hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is not treated in time, this increases the risk of local and systemic complications. The s2k guideline published in 2024 is intended to help reduce diagnosis latency and improve treatment outcomes. Some important innovations have been incorporated at both the diagnostic and therapeutic level.

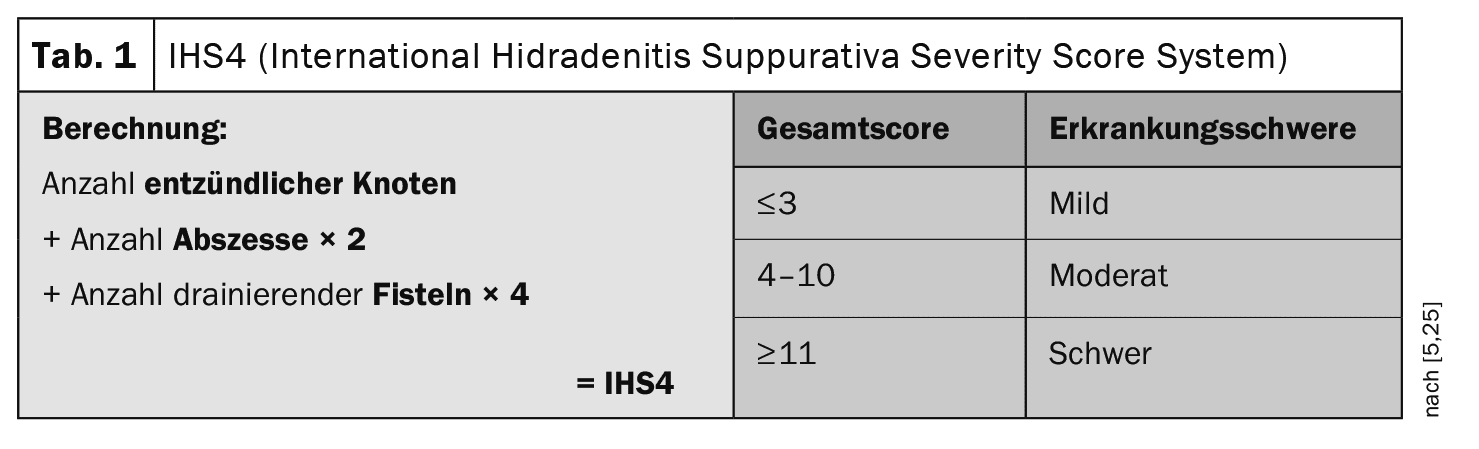

The primary efflorescences of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as “acne inversa”, are inflammatory nodules, abscesses and fistulas. According to current studies, HS is diagnosed with a delay of 7.2±8.7 years [1,2]. Phenotypically, a distinction is made between a non-inflammatory and an inflammatory form. Clinical scores are used to assess the severity and document the course of the disease. While the intensity of the inflammatory form can be divided into mild, moderate and severe HS using the IHS4 (International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Scoring) classificationand treated with medication accordingly, the Hurley classification (grades I–III) is used for the predominantly non-inflammatory form as a basis for deciding on possible surgical treatment [2,3]. While the Hurley classification was first described in 1989, the IHS4 has only been around for a few years [4,5]. “The IHS4 makes our lives easier,” says PD Dr. med. Florian Anzengruber, Senior Physician and Head of Dermatology/Allergology, Cantonal Hospital Graubünden [6]. It is a very simple score to use. Correct classification and assessment of disease activity is an important basis for decision-making when selecting treatment.

Counteract local and systemic complications

Early diagnosis and treatment of HS is a key factor in achieving good control of disease activity and preventing systemic complications.

- Acute local complications are mainly cutaneous superinfections. Chronic local complications, which may develop in particular due to prolonged anogenital inflammation, include lymphoedema, including scrotal elephantiasis. Concurrent reactive lymphadenopathy is usually associated with late-stage disease, sometimes as a result of secondary infections [7]. In severe HS and Hurley grade III in particular, scarring, contracture and blockage of the lymphatics can lead to accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the interstitial tissue and/or proximal saccular dilatation of the lymphatic vessels. Scarring in severe HS can lead to restricted movement (especially in axillary manifestations) due to the resulting scarring. Genitoanal localization can lead to strictures of the urethra, anus and rectum and occasionally pararectal and paraurethral fistulas can be observed.

- Chronic, systemic complications can significantly impair the patient’s quality of life [8]. Systemic complications include chronic pain and, less commonly, systemic amyloidosis with subsequent renal, cardiac and central nervous system damage, anemia and hypoproteinemia. Patients with severe HS should be screened for microalbuminuria or proteinuria and a renal biopsy should be considered if necessary.

- Squamous cell carcinoma occurs as a complication of chronic, untreated HS and shows androtropism (78%), an early, high risk of metastasis (54%) and a poor prognosis (59% mortality) [9]. In addition, HS can be a severe psychological burden, accompanied by restrictions in social contacts and social withdrawal of patients [10]. HS patients have an increased risk of depression.

Drug therapy: utilizing “windows of opportunity”

Treatment depends on the severity of the HS. The guideline emphasizes that the earlier the disease is detected, diagnosed and treated, the greater the chance of successful treatment. One aim is to prevent further extensive scarring and associated local and systemic complications [6].

Topical and intralesional therapies: Regular skin care is important to improve the barrier function in the affected areas. Topical therapy with clindamycin 1% solution should be recommended for mild HS and as an adjunctive medication to systemic or surgical therapy for moderate to severe HS. Topical therapy with resorcinol peeling 15% may be considered in patients with mild to moderate HS. Intralesional injections with corticosteroids can achieve temporary improvement of individual lesions [11]. Intralesional corticosteroid therapy should be recommended for the treatment of acute inflammatory lesions. On the other hand, intraoperative intralesional gentamycin is not recommended.

Classic systemic therapies: The guideline points out that the mechanism of action of systemically applied antibiotics in HS is less about reducing the colonization of the hair follicles with bacteria and more about modulating inflammatory processes. Clindamycin is one of the most frequently used antibiotics in HS. Rifampicin, for example, is suitable for the treatment of granulomatous infections. Ertapenem is an active substance from the carbapenem group. The treatment recommendations are shown in Table 2 [1]. In the case of treatment with systemic antibiotics, a review of the appropriateness and possible switch to another form of treatment (biologics, surgical excision) should be recommended after three months at the latest. Laboratory tests (blood count, liver values) can be considered before antibiotic therapy. During treatment with rifampicin, regular checks of the liver and kidney parameters as well as the blood count should be recommended.

In addition to antibiotics, immunosuppressants are also among the classic systemic treatment options for HS. Systemic corticosteroids lead to an initial improvement, but a deterioration can occur if the dose is reduced or discontinued. Oral systemic therapy with corticosteroids (e.g. Ciclosporin A) can be considered. The use of methotrexate or azathioprine is not recommended.

Systemic oral therapy with apremilast may be considered in patients with moderate to severe HS. The guideline contains recommendations on a whole range of other systemic active substances such as hormonal antiandrogens, retinoids, metformin, dapsone and zinc gluconate. Oral systemic monotherapy with colchicine and intramuscular human immunoglobulin are not recommended.

Biologics – extended spectrum: The guideline recommendations for the use of biologics in inflammatory HS are shown in Figure 1. The number of clinical studies with biologics is constantly increasing and the range of available active substances has expanded. In addition to the TNF-alpha inhibitor adalimumab, the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (s.c.) has also been approved in Switzerland since 2023 and bimekizumab (s.c.) – an IL-17A/F inhibitor – has also been approved for the treatment of HS in other countries. IL-17 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy is based on the fact that several studies have shown an increased number of Th17 cells and overexpression of IL-17 in HS [12–14].

- Secukinumab (s.c.) 300 mg every 2 weeks achieved a HiSCR response of 45% and 42.3% after 12 weeks in the randomized Phase III studies SUNSHINE and SUNRISE compared to 33.7% and 31.2% with placebo [15]. Administration of the same dose of secukinumab at 4-week intervals achieved HiSCR responses of 41.8% and 46.1% after 12 weeks compared to 33.7% and 31.2% with placebo. In both studies, treatment with both secukinumab regimens was generally well tolerated. The recommended dosing regimen is as follows: secukinumab 300 mg with starting doses at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4, followed by monthly maintenance doses. Based on the clinical response, the maintenance dose can be increased to 300 mg every 2 weeks.

- Bimekizumab was investigated in a randomized controlled phase II study with 90 patients [16]. At week 12, of the 46 patients receiving bimekizumab at a dose of 320 mg every two weeks, 57.3% achieved HiSCR compared to 26.1% of the placebo group. Bimekizumab was associated with an improvement in IHS4 (16.0; SD** 18.0) compared to the placebo group (40.2; SD 32.6). At week 12, 46% of bimekizumab-treated patients reached HiSCR75 and 32% reached HiSCR90, while 10% of placebo-treated patients reached HiSCR75 and none reached HiSCR90.

** SD = standard deviation

Surgical interventions and laser therapy: Surgical therapy is a therapeutic option or complementary treatment modality in all stages of HS [17]. Depending on the stage, the available spectrum ranges from the individual removal of cysts, so-called deroofing (opening of the abscess cavity with a punch or scalpel) to the complete treatment of entire areas. In the case of acute abscess formation, incision and drainage are sensible options, followed by obligatory medical or further surgical treatment. In more severe HS, extensive, complete removal of the damaged tissue is indicated, especially in the predominantly non-inflammatory form [18]. There are several surgical techniques that are currently used [19–22]. The general surgical approach is to remove all irreversibly damaged tissue.

Laser procedures can sometimes be used as an alternative to surgical interventions. According to the guideline, ablation of HS lesions with theCO2 laser should be recommended as an alternative to traditional surgery. The use of the long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser can be recommended both as an alternative anti-inflammatory therapy and for the destruction of hair follicles as secondary prevention.

Further interventions incl. lifestyle: In addition to the therapeutic interventions mentioned, the guideline discusses other treatment options, including off-label options. Pain therapy and lifestyle modification are important accompanying measures. The latter primarily includes weight reduction and smoking cessation, as smoking and overweight/obesity have an additive effect on HS [23]. Over 40% of HS patients suffer from metabolic syndrome and over 60% from abdominal obesity. The metabolic syndrome (obesity, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension and/or hyperglycemia) appears to be pathogenetically relevant for HS and studies show pathogenetically relevant links between obesity and HS [24]. Smoking is also an established trigger factor for HS. The guideline recommends examining HS patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, physical inactivity, smoking, overweight/obesity and dyslipidemia and advising them accordingly [1].

Congress: SGDV Annual Congress

Literature:

- Zouboulis CC, et al: S2k guideline on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa (ICD-10 code: L73.2). 2024: AWMF registry no.: 013-012. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/013-012l_S2k_Therapie-Hidradenitis-suppurativa-Acne-inversa_2024-08.pdf,(last accessed 28.11.2024).

- Saunte DM, et al: Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol 2015; 173: 1546-1549.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: Hidradenitis Suppurativa/Acne Inversa: Criteria for Diagnosis, Severity Assessment, Classification and Disease Evaluation. Dermatology 2015; 231: 184-190.

- Hurley HJ: Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach In: Dermatologic Surgery: Principles and Practice (Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH, eds). New York: Marcel Dekker 1989; 729-739.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 1401-1409.

- “Empowering patients, enhancing care: new guidelines and patient insights in HS management”, satellite symposium, SGDV Annual Congress, Basel, 20.09.2024.

- Nazzaro G, et al: Lymph node involvement in hidradenitis suppurativa: Ultrasound and color Doppler study of 85 patients. Skin Res Technol 2020; 26: 960-962.

- Yuan JT, Naik HB: Complications of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2017; 36:79-85.

- Sachdeva M, et al: Squamous cell carcinoma arising within hidradenitis suppurativa: a literature review. Int J Dermatol 2021; 60: e459-465.

- Ooi XT, et al: The psychosocial burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in Singapore. JAAD Int 2023; 10: 89-94.

- Revuz J: Hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23: 985-998.

- Schlapbach C, et al: Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD 2011; 65: 790-798.

- Kelly G, et al: Dysregulated cytokine expression in lesional and nonlesional skin in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2015; 173: 1431-1439.

- Moran B, et al: Hidradenitis Suppurativa Is Characterized by Dysregulation of the Th17:Treg Cell Axis, Which Is Corrected by Anti-TNF Therapy. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 2389-2395.

- Kimball AB, et al: Secukinumab in moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa (SUNSHINE and SUNRISE): week 16 and week 52 results of two identical, multicentre, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trials. Lancet 2023; 401: 747-761.

- Glatt S, et al: Efficacy and Safety of Bimekizumab in Moderate to Severe Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Phase 2, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 1279-1288.

- Schwarz B: Hidradenitis suppurativa/Acne inversa: Challenges of outpatient care. Dermatology Practice 2024; Vol. 34, No. 4: 6-15.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: What causes hidradenitis suppurativa ?-15 years after. Exp Dermatol 2020; 29: 1154-1170.

- Mikkelsen PR, et al: Recurrence rate and patient satisfaction ofCO2 laser evaporation of lesions in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study. Dermatol Surg 2015; 41: 255-260.

- Cuenca-Barrales C, et al. : Patterns of Surgical Recurrence in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatology 2023; 239: 255-261.

- Ovadja ZN, et al: Recurrence Rates Following Reconstruction Strategies After Wide Excision of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dermatol Surg 2021; 47: e106-110.

- Riddle A, et al: Current Surgical Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dermatol Surg 2021; 47: 349-354.

- Cesko E, Korber A, Dissemond J: Smoking and obesity are associated factors in acne inversa: results of a retrospective investigation in 100 patients. Eur J Dermatol 2009; 19: 490-493.

- Sabat R, et al: Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with acne inversa. PLoS One 2012;7: e31810.

- Tzellos T, et al: Development and validation of IHS4-55, an IHS4 dichotomous outcome to assess treatment effect for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023; 37(2): 395-340.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2024; 34(6): 25-27 (published on 13.12.24, ahead of print)

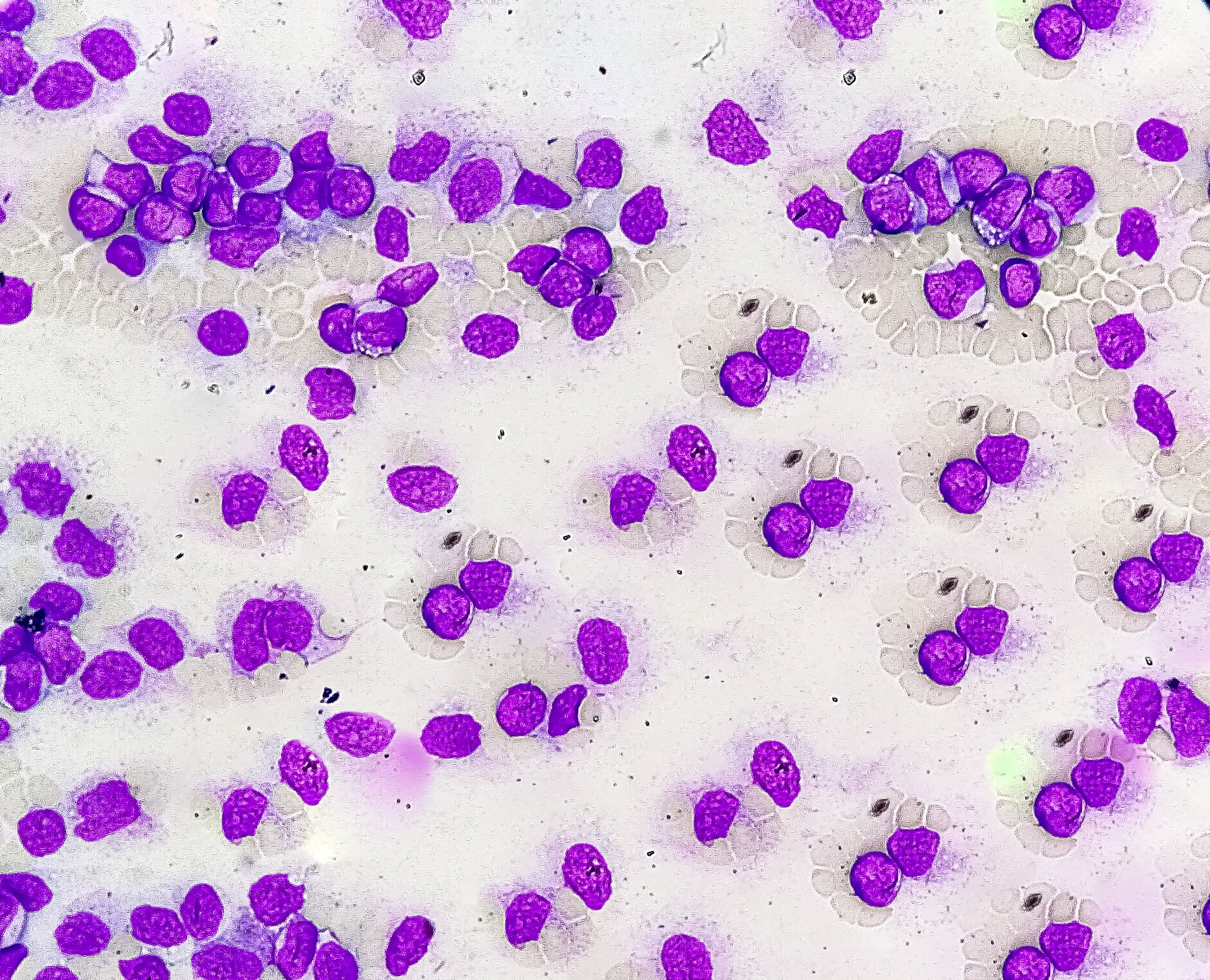

Cover picture: Acne inversa, Hurley stage II; © Dr. Thomas Brinkmeier, wikimedia