Therapy for non-small cell lung cancer is individualized and based on tumor stage, histology, and predictive molecular markers, taking into account the patient profile. To maximize the therapeutic outcome for each individual patient, coordination of the various therapeutic modalities by a tumor board is essential. This applies to curative but also to palliative situations.

The diagnosis, staging, and treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) require collaboration between multiple disciplines. The different therapeutic modalities have to be combined for an individual therapy regime. The Tumor Board is the central coordination platform for this. It would be desirable if all patients were presented to and discussed in a tumor board prior to initiation of curative or palliative therapy in order to determine an individualized and thus optimal therapeutic concept by coordinating the various therapeutic modalities. For this purpose, the factors of stage, histology, molecular analyses, comorbidities, quality of life and personal wishes and needs of the patient must be included. Pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, radiotherapists, pathologists, radiologists, and nuclear medicine specialists develop a joint decision that defines the therapy. Such close cooperation is also important during the course of a disease in order to be able to offer the best individual therapy again in the event of a new disease situation, such as a relapse.

The tumor board discussion for new diagnosis of non-small cell lung carcinoma can be described as follows: Tumors confined to the lung are resected primarily. Neo- or adjuvant therapy should always be discussed in cases of mediastinal lymph node involvement and/or infiltration into the surrounding area. In local advanced stages, patients are treated with multimodality approaches, i.e., combined chemotherapy followed by surgery or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. For metastatic lung cancer, therapy is determined based on histology and molecular characteristics.

Staging by PET-CT

Assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes: In early stages of the tumor, mediastinal lymph node staging with high sensitivity and specificity should be requested, as its result has high relevance for the further procedure. The clinical significance of PET-CT for lymph node staging is its high negative predictive value. If PET-CT is negative, further invasive lymph node diagnostics can be omitted.

In contrast, the positive predictive value is lower. PET-positive mediastinal lymph nodes consequently require further evaluation. For this purpose, bronchoscopic punctures are now used as the primary, less invasive techniques (endobronchial sonography [EBUS], endosonography [EUS]), or if necessary, mediastinoscopy.

Extrathoracic manifestations: Another strength of PET-CT is the ability to detect extrathoracic metastases. For adequate staging of the CNS, MRI of the skull should be performed if clinical suspicion or mediastinal lymph node metastasis is detected [1].

Therapy early stages

Non-small cell lung carcinoma confined to the lung without extrathoracic metastases can be treated by surgical resection with curative intent. The median survival after surgery is 46 months – without therapy only 14 months – but depends significantly on the initial tumor size and lymph node involvement. The most important criterion for a good treatment result is the experience of the treating team. It has also been shown that centers with many operations (>150 per year) can achieve better overall survival than those with fewer cases (<70 per year) [2].

In stages I and II, lobectomy including mediastinal lymphadenectomy is attempted. The 30-day mortality after lobectomies is low (1%) and not increased even in elderly patients with comorbidities when carefully selected. The operation can be performed minimally invasively by thoracoscopy.

Pneumonectomies are only necessary in exceptional cases today, but may have a place in an overall curative concept [3]. They can be prevented by selective cuff resection of affected bronchi or arteries and reanastomosis of remaining lung tissue (cuff resection, “sleeve resection”). Such resections are becoming increasingly common. Example: In the case of a central upper lobe carcinoma, the remaining middle and lower lobes are reanastomosed to the main bronchus after its resection.

Other lung tissue-sparing procedures, such as segmentectomies, are recommended only for small, peripheral tumors (<2 cm) without lymph node metastases (N0) [4].

Minimally invasive (thoracoscopic) lobectomy is considered as a surgical technique for localized bronchus carcinoma and is used in specialized centers at earlier stages. Patients after thoracoscopic lobectomy have 5-year survival comparable to (or in some studies better than) after open lobectomy [5]. In addition, adjuvant chemotherapy is tolerated earlier and better.

In patients with small tumors and significant comorbidities, curative intentional radiotherapy should be considered, with a dignity diagnosis made in advance whenever possible. Tissue harvesting is particularly important in order to later offer further optimal therapy based on the molecular characteristics of the tumor. Stereotactic radiotherapy (SBRT) and high-precision techniques (e.g., Gamma Knife®, LINAC) are used in this setting, allowing good local tumor control with limited radiation toxicity [6].

Therapy of locally advanced stages with curative intention

In patients with stage IIIA (N2) tumors, defined by the presence of ipsilateral mediastinal lymph node metastases, a multimodal curative approach can be developed if the patient is in good general health.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be recommended in the sense of induction chemotherapy if the situation is judged to be potentially operable. Since chemotherapy is an important component of the therapeutic regimen in this situation, neoadjuvant administration ensures that systemic therapy can be given without dose reduction while being well tolerated [7, 8].

Definitive radio-chemotherapy may be recommended for patients with unresectable primary tumors, with concomitant radiation/chemotherapy recommended for patients in good general status [9].

Currently, a study in Switzerland is investigating whether the addition of preoperative radiotherapy in combination with cetuximab to chemotherapy is beneficial in far advanced non-metastatic situation (IIIB) (SAKK 16/08).

Adjuvant therapy after surgery

In patients after complete resection of stage II and III non-small cell lung cancer, four cycles of adjuvant cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy are now considered standard therapy. Based on retrospective analyses (CALGB 9633), adjuvant therapy can be recommended even in stage IB and tumor size greater than 4 cm.

In patients after complete tumor resection in stage IB-IIB, three large randomized trials now demonstrate a significant prolongation of survival with adjuvant platinum-based combination chemotherapies [10–12].

Post-operative radiation therapy (PORT) remains controversial. Again, studies are underway to better describe the value. For example, the LungART trial is testing PORT for patients with N2 involvement after complete resection (Abstract 7658, ASCO 2007).

However, only a proportion of those treated benefit from adjuvant treatment. Thus, the question arises of biological characteristics that could allow the identification of such patients in advance. Currently, we are investigating the extent to which gene expression signatures can be used to identify subgroups with different prognosis and whether this can be used to focus adjuvant therapies on patients with unfavorable prognosis (CALGB-30506). Alternatively, pharmacogenomic studies are also used to try to predict whether certain chemotherapeutic agents can influence the tumor. However, no predictive markers have yet been characterized.

Palliative therapy based on histology and molecular biology

Therapeutic strategies in palliative care have changed in recent years. The new strategies are based on the “rediscovered” relevance of differential morphology and on new molecular findings. The generic term “non-small cell lung cancer” is no longer sufficient for the treatment decision. The term “non-small cell” summarizes histologically and molecularly extremely heterogeneous entities. It no longer meets the needs of modern drug selection individually tailored to morphology and molecular biology.

Targeted therapy according to exact histology and, in the case of adenocarcinomas, the mutation status of the “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor” (EGFR) and the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) translocation status (EML4-ALK positive) has become established in everyday oncological practice. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can be used here with therapeutic benefit.

Crucial: The mutation status of the tumor cells

Today, non-small cell lung carcinomas should be tested for their mutation status before initiating palliative therapy. All non-squamous cell lung cancers need to be dissected for the presence of EGFR mutations. Mutations can lead to activation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase of EGFR, giving tumor cells a permanent growth signal. This is called an activating mutation. These mutations are most common in nonsmokers [13]. The most relevant of the EGFR mutations are a deletion in exon 19 and the point mutation L858R (exon 21) and G719X (exon 18). However, there are also mutations such as T790M (exon 20) that confer resistance to TKI therapy. Drugs that can be used are gefitinib and erlotinib, which inhibit the tyrosine kinase of EGFR [14]. Afatinib is already approved as a second-line treatment in the US and EU. Afatinib blocks “Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2” (HER2/ErbB2) and ErbB4 in addition to the “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor” (EGFR/ErbB1). In patients with known activating EGFR mutation, tyrosine kinase inhibitor should be used in the first line.

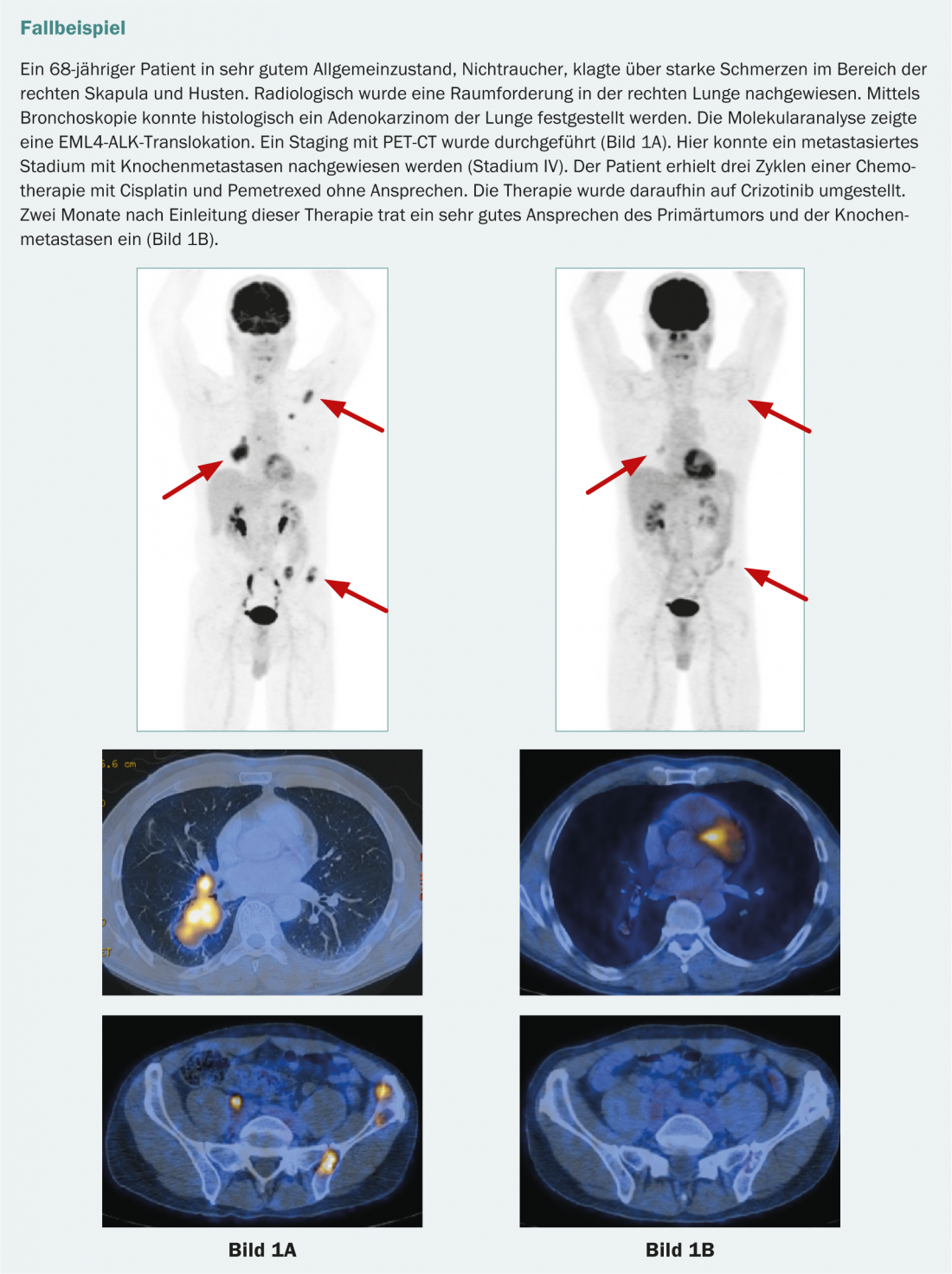

Likewise, in adenocarcinoma of the lung, there may be a pathological fusion protein consisting of “anaplastic lymphoma kinase” (ALK) and “echinoderm micro-tubule-associated protein-like 4” (EML4). This also leads to an uncontrolled growth signal in the tumor cells. This mutation occurs much less frequently (approx. 4-7%). It primarily affects non-smokers and almost never occurs in combination with other mutations [15]. Patients who are EML4-ALK positive benefit from treatment with crizotinib. Currently, crizotinib is approved in Switzerland as second-line therapy in patients with ALK translocation.

Other rare mutations for which potential tyrosine kinase inhibitors exist involve the EGF-2 receptor (HER2) and BRAF. Almost exclusively in adenocarcinomas of smokers, mutations of the KRAS oncogene (G-to-T transversion) are also observed. The presence of a KRAS mutation correlates with an overall poorer prognosis. At the moment, however, no therapeutic consequence can be drawn from this mutation [16].

Histology points the way to chemotherapy

The histologic classification of adenocarcinoma of the lung was renewed, replacing the ambiguously defined term “bronchio-alveolar carcinoma (BAC).” Small pre-invasive lesions are now referred to as “adenocarcinoma in situ”. Invasive lesions >5 cm are referred to as “lepidic carcinoma”. Carcinomas between 3 and 5 cm are referred to as “minimally invasive” [17].

Furthermore, platinum-containing combination chemotherapy – with agents such as vinorelbine, gemcitabine, pemetrexed, and paclitaxel – should be considered the standard or first-line therapy for advanced bronchus carcinoma [18].

Despite great efforts, it has not yet been possible to define reliable predictive markers for chemotherapeutic agents 19, 20].

Pemetrexed is approved for the treatment of non-squamous cell carcinoma. Pemetrexed is a new member of the folic acid antagonist family. In 2008, a randomized trial showed that patients with non-plate epithelial histology benefited better from combination therapy with pemetrexed and cisplatin compared with the gemcitabine/cisplatin combination. The side effect profile of the new combination also proved superior in terms of hematologic toxicity and febrile neutropenia [21].

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy is approved in Switzerland for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with non-squamous histology. This was based on two randomized trials: On the one hand, the addition of bevacizumab to the carboplatin/paclitaxel combination improved tumor response and prolonged median survival by 12.3 months – i.e. more than chemotherapy alone (10.3 months) [22]. On the other hand, bevacizumab in combination with cisplatin/gemcitabine achieved significantly higher tumor response [23]. However, this did not result in a prolongation of overall survival [24].

Maintenance therapy

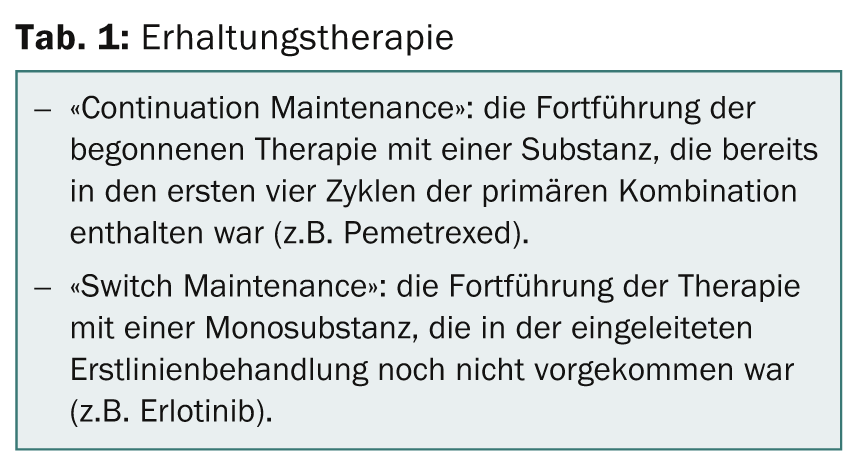

Treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer was usually with four (to a maximum of six) platinum-containing chemotherapy cycles. The results of new randomized trials showed for the first time that in certain situations, continuation of treatment with downstream maintenance therapy can prolong survival. Two forms of maintenance therapy are distinguished (Table 1) . For “continuation maintenance”, data are available for gemcitabine [25] and pemetrexed plus bevacizumab [26], which showed an advantage in terms of progression-free survival. Switch maintenance tested positive for pemetrexed [27], docetaxel [28], erlotinib [25], and gefitinib [29].

Metastasis surgery

In metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, i.e. stage IV, surgery has a limited role and is always a case-by-case decision. In appropriate cases, neurosurgical resection is performed for a singular brain metastasis of operable bronchus carcinoma. This is followed by whole brain irradiation and surgical resection of the primary tumor if there are no other metastases elsewhere. With radical resection, this procedure achieves a 5-year survival rate of approximately 40%.

In special situations with isolated organ metastases, especially adrenal metastases, surgical resection with curative intent has also been evaluated [30]. Such interventions are usually combined with adjuvant or neo-adjuvant systemic therapy.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Accurate staging, histologic diagnosis, and molecular analysis are key to individualized therapy and thus to optimized therapeutic outcomes.

- The term “non-small cell lung cancer” encompasses morphologically and molecularly many different entities that should be accurately described in one diagnosis.

- Today, individualized, palliative first-line therapy is possible according to precise histological differentiation and according to mutation status. After completion of four cycles of first-line platinum-containing therapy, maintenance therapy improves progression-free survival and may result in improved overall survival. Patients with stabilized disease and a good general condition seem to benefit most.

- Minimally invasive (thoracoscopic) lobectomies are now preferred for localized bronchus carcinoma. For centrally located tumors, lung tissue-preserving cuff/sleeve resection is increasingly chosen.

- Adjuvant cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy is now an integral part of therapy after resection of tumor stages IB (>4 cm), II, and IIIA.

PD Ulf Petrausch, M.D.

Alessandra Curioni-Fontecedro, M.D.

Literature:

- Silvestri GA, et al: Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143(5 Suppl): e211S-50S.

- Luchtenborg M, et al: High procedure volume is strongly associated with improved survival after lung cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(25): 3141-3146.

- Riquet M, et al: A review of 250 ten-year survivors after pneumonectomy for non-small-cell lung cancer. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery 2013.

- Yendamuri S, et al: Temporal trends in outcomes following sublobar and lobar resections for small (≤2 cm) non-small cell lung cancers – a Surveillance Epidemiology End Results database analysis. The Journal of surgical research 2013; 183(1): 27-32.

- Lee PC, et al: Long-term survival after lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer by video-assisted thoracic surgery versus thoracotomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery 2013; 96(3): 951-960; discussion 960-961.

- Powell JW, et al: Treatment advances for medically inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer: emphasis on prospective trials. The lancet oncology 2009; 10(9): 885-894.

- Scagliotti GV, et al: Randomized phase III study of surgery alone or surgery plus preoperative cisplatin and gemcitabine in stages IB to IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(2): 172-178.

- Strauss GM: Induction chemotherapy and surgery for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: what have we learned from randomized trials? J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(2): 128-131.

- Auperin A, et al: Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(13): 2181-2190.

- 10. Winton TL, et al: A prospective randomised trial of adjuvant vinorelbine (VIN) and cisplatin (CIS) in completely resected stage 1B and II non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Intergroup JBR.10. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22(14): 621s-621s.

- 11. le Chevalier T, et al: Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. NEJM 2004; 350(4): 351-360.

- Pignon JP, et al: Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(21): 3552-3559.

- Rosell R, et al: Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2009; 361(10): 958-967.

- Rosell R, Bivona TG, Karachaliou N: Genetics and biomarkers in personalisation of lung cancer treatment. Lancet 2013; 382(9893): 720-731.

- Shaw AT, et al: Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(26): 4247-4253.

- Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE: KRAS Mutation: Should We Test for It, and Does It Matter? J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(8): 1112-1121.

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Riely GJ: New pathologic classification of lung cancer: relevance for clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(8): 992-1001.

- Schiller JH, et al: Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. NEJM 2002; 346(2): 92-98.

- Cobo M, et al: Customizing cisplatin based on quantitative excision repair cross-complementing 1 mRNA expression: a phase III trial in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(19): 2747-2754.

- Bepler G, et al: Randomized international phase III trial of ERCC1 and RRM1 expression-based chemotherapy versus gemcitabine/carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(19): 2404-2412.

- Scagliotti GV,et al: Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(21): 3543-3551.

- Sandler A, et al: Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. NEJM 2006; 355(24): 2542-2550.

- Reck M, et al: Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(8): 1227-1234.

- Reck M, et al: Overall survival with cisplatin-gemcitabine and bevacizumab or placebo as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised phase III trial (AVAiL). Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO 2010; 21(9): 1804-1809.

- Perol M, et al: Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(28): 3516-3524.

- Barlesi F, et al: Randomized phase III trial of maintenance bevacizumab with or without pemetrexed after first-line induction with bevacizumab, cisplatin, and pemetrexed in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAPERL (MO22089). J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(24): 3004-3011.

- Belani CP, et al: Quality of life in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer given maintenance treatment with pemetrexed versus placebo (H3E-MC-JMEN): results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncology 2012; 13(3): 292-299.

- Fidias PM, et al: Phase III Study of Immediate Compared With Delayed Docetaxel After Front-Line Therapy With Gemcitabine Plus Carboplatin in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(4): 591-598.

- Zhang L, et al: Gefitinib versus placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (INFORM; C-TONG 0804): a multicentre, double-blind randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology 2012; 13(5): 466-475.

- Salah S, Tanvetyanon T, Abbasi S: Metastatectomy for extra-cranial extra-adrenal non-small cell lung cancer solitary metastases: Systematic review and analysis of reported cases. Lung Cancer-J Iaslc 2012; 75(1): 9-14.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2013; 1(1): 16-21.