For the majority of melanoma patients, much more effective therapies are available today than a few years ago. This also applies to adjuvant melanoma treatment. Many new therapeutic approaches have been established and are being successively investigated in larger and smaller studies. This includes the interim analysis presented at this year’s ADF Annual Meeting.

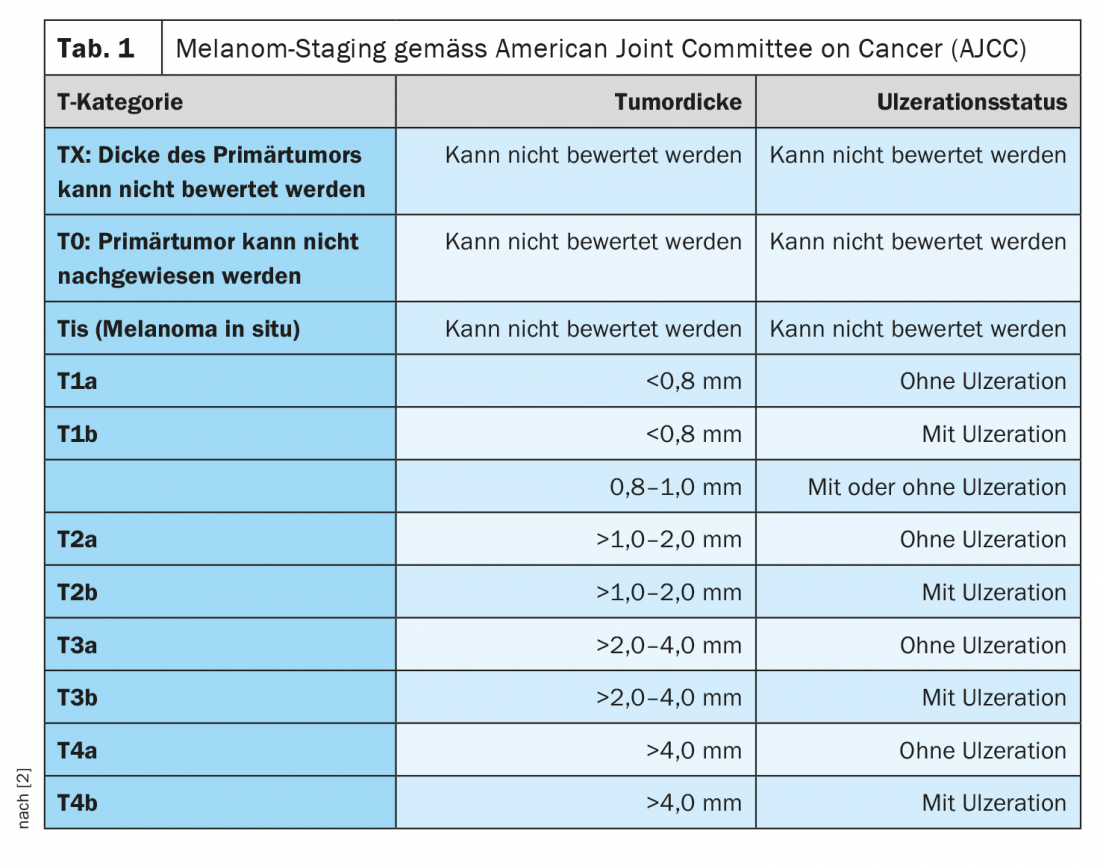

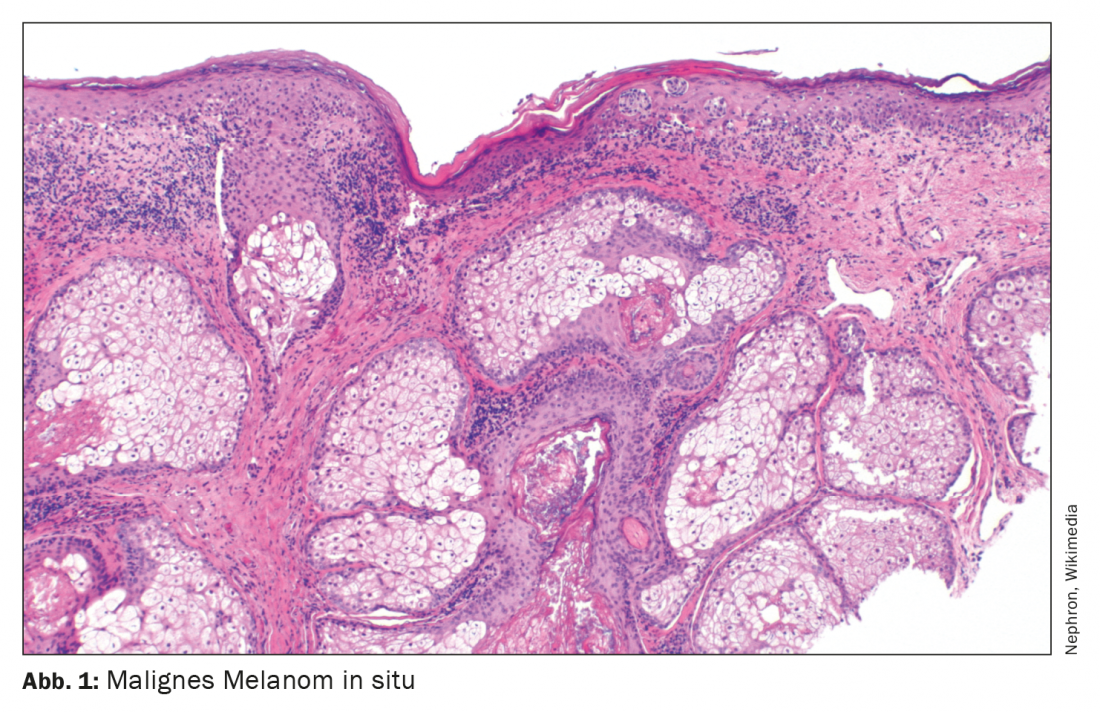

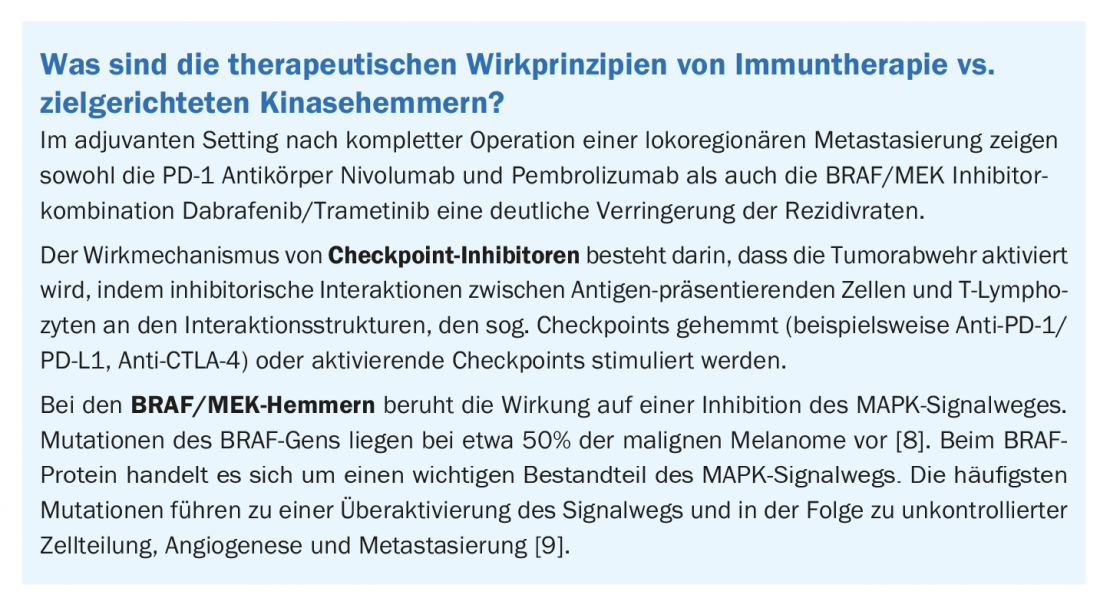

Each year, it is estimated that approximately 200,000 people worldwide develop malignant melanoma [1]. The incidence has steadily increased during the past decades. The median age of onset is approximately 60 years for women and 64 years for men. Classification and staging of malignant melanoma are currently based on the eighth edition of the AJCC classification (Table 1) [2]. In addition to tumor thickness according to Breslow, the presence of ulceration and lymph node involvement at initial diagnosis are considered important prognostic criteria [1]. Until a few years ago, the standard of care for advanced and metastatic melanoma was palliative with a median survival of 6 to 12 months. Chemotherapies were considered the standard of care. The launch of highly effective treatment options from the field of checkpoint inhibitors as well as targeted kinase inhibitors such as BRAF and MEK inhibitors has significantly improved the life expectancy of patients with completely resected melanoma.

Checkpoint inhibitors were the pioneers – what about today?

Since the launch of ipilimumab in 2011, further progress has been made in the field of immunotherapy for melanoma patients. With regard to adjuvant treatment, this is documented, among others, by the KEYNOTE-054 trial [3], in which nivolumab showed a significant advantage for recurrence-free survival compared to ipilimumab. And in the Checkmate-238 trial, pembrolizumab proved superior to placebo in terms of relapse-free survival [4]. The risk reduction was 35% for nivolumab vs. ipilimumab and 43% for pembrolizumab vs. placebo, respectively. The randomized trial conducted with nivolumab versus ipilimumab also demonstrated a significant improvement in distant metastasis-free survival (HR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.55-0.95]. With regard to the risk-benefit profile, the current AWMF guideline states that, despite a latent risk of potentially serious side effects, the benefit of a risk reduction speaks in favor of the use of this therapy option. [5].

BRAF and MEK inhibitors expand the spectrum of highly effective substances

For adjuvant therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors, the current S3 guideline includes a randomized-controlled, double-blind phase III trial of dabrafenib/trametinib called. Patients in stages IIIA (minimum diameter in affected lymph node >1 mm) to IIIC with a BRAFV600E or V600K mutation received dabrafenib 150 mg 2× daily and trametinib 2 mg 1× daily, or comparable placebo treatment, for a total of 12 months [6]. After a median follow-up of 2.8 years, the 3-year probability of relapse-free survival was 58% for the treatment arm and 39% for the placebo arm (HR for relapse or death 0.47; 95% CI: 0.39-0.58; p<0.001). According to the current S3 guideline, the use of these therapy options is to be advocated despite a relatively high side effect-related discontinuation rate in view of the proven benefit: risk reduction of 53% for recurrence-free survival and 43% for melanoma-related death.

Interim results of a cross-regional data set of the DACH region.

At this year’s ADF Annual Meeting, data were presented from an interim analysis of a retrospective study in which melanoma patients from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (DACH) received pembrolizumab and nivolumab (anti PD-1) or dabrafenib/trametinib (BRAF/MEK inhibition) as adjuvant therapy from 1/2017 to 2/2020 [7]. In September 2020, data from 524 patients of the total 1039 study participants were analyzed. The two adjuvant treatment options were compared in terms of 12-month PFS and other relevant outcome parameters.

Patient characteristics of the subpopulations treated with BRAF/MEK inhibition vs. anti PD1 therapy were comparable with respect to demographic variables and tumor characteristics. The majority of patients received adjuvant PD1 therapy (n=439; 83.8%; Nivo=69.2%; Pembro=30.8%). The average follow-up period was 13.1 months. The time interval from complete resection to start of adjuvant treatment was 2.5 months (SD=1.55) for BRAF/MEK inhibition and 2.7 months (SD=2.62) for anti-PD1 therapy. The mean duration of therapy spanned 7.4 months (SD=4.4) for both treatment regimens. Statistical analyses revealed a 12-month PFS of 81.2% for the anti-PD1 subgroup and 90.4% for study participants treated with BRAF/MEK inhibition (OR 2.001; 95% CI: 1.045-3.830; p=0.036). No difference in PFS was seen between patients receiving nivolumab vs. pembrolizumab.

In both the BRAF/MEK inhibition and anti-PD1 treatment groups, ulceration, greater tumor thickness, and more metastatic lymph node involvement were negative predictors of PFS. Positive predictors of more favorable PFS were higher BMI (25-30) and male sex in patients receiving BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy. PFS did not differ depending on complete lymph node dissection vs sentinel lymph node biopsy.

The safety profile of all investigated active substances proved to be comparable to previous studies. The rate of drug-associated adverse events (drAE) and immune-related AEs was similar among nivolumab compared with pembrolizumab (64.2-63.7% and 33.3-33.8%, respectively). Among patients treated with BRAF/MEK inhibition, the proportion of drAE was 87% in this study. The authors do not provide further details on the nature of the side effects. To find out more about the patient characteristics and tumor characteristics that correlate with a favorable response to anti-PD1 vs BRAF/MEK inhibition as adjuvant therapy regimens, further analyses are planned.

Congress: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Forschung 2021

Literature:

- Lamos C, Hunger RE: Checkpoint inhibitors-indication and use in melanoma patients [Checkpoint inhibitors-indications and application in melanoma patients]. Z Rheumatol 2020;79(8): 818-825.

- Gershenwald JE, et al; for members of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(6): 472-492.

- Weber J, et al: Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(19): 1824-1835.

- Eggermont AMM, et al: Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(19): 1789-1801.

- AWMF: S3 Guideline on Diagnosis, Therapy and Follow-up of Melanoma Version 3.3 – July 2020 AWMF Registry Number: 032/024OL

- Long GV, et al: Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(19): 1813-1823.

- Schumann K, et al: P048 Adjuvant melanoma treatment: real-world data from the DACH region, 47th Annual Meeting of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Forschung (ADF) Virtual, 04.03.-06.03.2021.

- Schadendorf D, et al: Melanoma. Lancet 2018; 392: 971-984.

- Arozarena I, Wellbrock C: Overcoming resistance to BRAF inhibitors. Ann Transl Med 2017; 5: 387

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(4): 44-45 (published 8/18-21; ahead of print).