Often dismissed as a disease of affluence, sufferers suffer the physical and social consequences of their obesity. However, elaborate diets and expensive fitness subscriptions do not always bring the desired weight loss. Obese patients can be supported by primary care physicians. This is especially true if the obesity is associated with consequential comorbidities.

Healthier lifestyle, more physical activity and more balanced diet. These are the first buzzwords that pop into your head when an obese patient presents to the family doctor’s office looking for help. Goal: weight reduction. However, many obese patients have already had several unsuccessful weight loss attempts at this point. What is behind the problem of obesity?

Problem obesity

In Switzerland, 41.9% of all people over 15 years of age in 2017 were affected by overweight (BMI >25) or obesity (BMI >30) [2]. This results in annual costs of around eight billion Swiss francs in Switzerland (as of 2012) [3]. Obesity in particular, i.e. severe overweight, is often associated with a high level of suffering. This is because obesity causes many secondary diseases, which can be categorized according to the 4M system:

- Metabolic concomitant diseases (lipid metabolism disorders, polycystic ovary syndrome, diabetes mellitus type 2)

- Mechanical concomitant diseases (arterial hypertension, sleep apnea, orthopedic problems).

- Concomitant mental disorders (depression, eating disorders)

- Monetary (social) problems (impairments in the context of job search or partnership, discrimination) [4].

Fat distribution

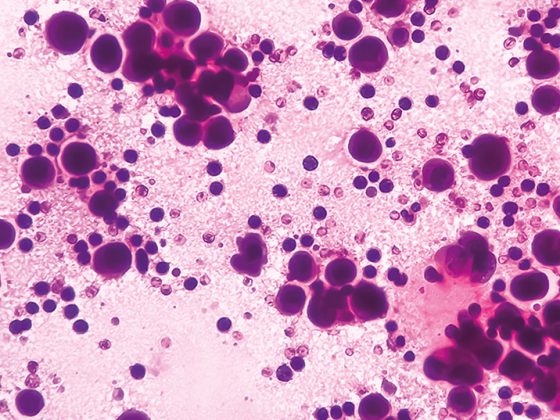

The determining factor for the occurrence of complications of obesity is fat distribution. A distinction is made between visceral, i.e. intra-abdominal, and subcutaneous fat. A high visceral fat content is critical, as this decreases insulin sensitivity. The underlying pathophysiology is complex. Histologically, visceral fat shows hypertrophic adipocytes with immune cell infiltration. Due to the increase in size of adipocytes, obesity results in persistent tissue expansion. In the process, more adipocytes die than usual. An inflammatory reaction is triggered, which is why histologically increased immune cells are visible, first and foremost the so-called Adipose Tissue Macrophages (ATM). The ATMs in turn release increased cytokines and extracellular RNA, leading to a maladaptive immune response. In the process, the physiological metabolism of the adipocytes is disturbed. They become insulin resistant.

Subcutaneous fat, on the other hand, often contributes little to the development of comorbidities. Therapeutically, this is relevant in that liposuction that reduces only subcutaneous fat has no direct effect on the development of sequelae.

Obesity diagnostics

How far is it worth going when evaluating obese patients? Diagnostically, looking at BMI is not enough. This is because BMI alone says nothing about the tissue composition of the body mass. For the assessment of cardiovascular and metabolic risk, waist circumference measurement is more informative, since fat distribution can be indirectly assessed. A waist circumference greater than 102 cm in men and greater than 88 cm in women is considered too high [4]. In certain indications, such as infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or suspected metabolic syndrome, more extensive laboratory diagnostics are recommended.

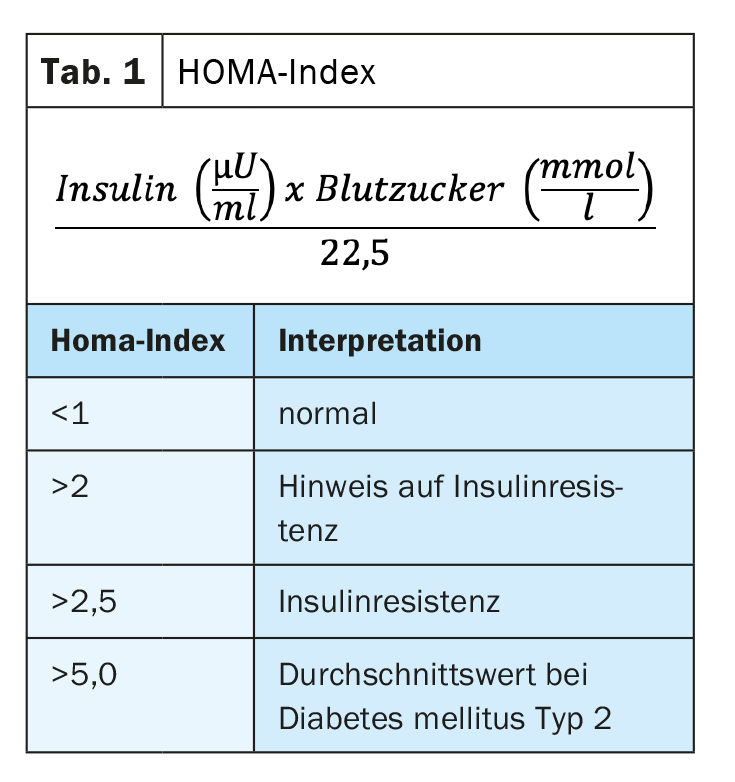

To assess insulin resistance, the HOMA index can be determined (Tab. 1). Care should be taken to use fasting values (at least eight hours of food abstinence).

Insulin resistance is a high risk factor for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), arterial hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, to assess the state of metabolic syndrome associated with mild chronic inflammation, it is recommended to take the following laboratory parameters:

- Kidney values

- Microalbumin (spontaneous urine)

- Liver values

- HDL cholesterol and triglycerides

- CRP (and hCRP)

- HbA1c

- SHBG (for fertility clarification)

Microalbuminuria provides an indication of whether the vasculature is involved and microangiopathy is beginning to develop.

At obesity centers, additional bioimpedance analysis is often available as another useful diagnostic tool. Bioimpedance analysis examines the electrical conductivity of tissue to infer tissue composition. This is especially useful if you want to make a history measurement. This is because it is crucial whether patients lose predominantly fat mass or at the same time a considerable proportion of metabolically active muscle mass. If the loss of metabolically active cell mass is too high, weight gain in the course, a so-called yoyo effect, is pre-programmed. Severe new weight gain can generally be prevented by adequate protein intake and increased physical activity.

Therapy options

For obesity, first line therapy consists of nutritional counseling and exercise enhancement – in other words, caloric negative balancing. For this purpose, there are practical models of nutritional consultations, in which professionals visit the practice upon request. In this way, time-consuming consultations with primary care physicians can be avoided. In addition, there are modern approaches such as nutritional counseling via app, so that continuous coaching is ensured.

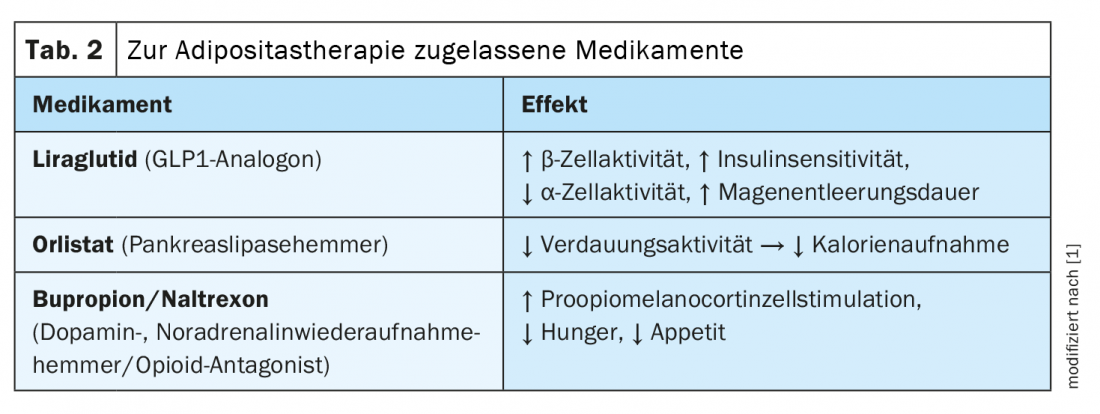

If conservative therapy does not bring the desired success, there are helpful medications that facilitate weight loss. The following drugs are approved for obesity treatment in Switzerland: Liraglutide, Orlistat and Bupropion/Naltrexone (Tab. 2).

Liraglutide and orlistat can be administered for up to three years if the indication persists, while the combination preparation bupropion/naltrexone can only be administered for up to three years with certain additional training. There is always the possibility of prescribing the medication at your own expense. Furthermore, the GLP1 analogue semaglutide, which achieved twice as good results in studies as the substance-class related liraglutide, is about to be approved.

The last pillar of therapy is bariatric surgery. In 60-70% of cases, satisfactory results are achieved over several years. Even with this invasive, but very effective method, successful long-term results are only ensured if a lifestyle adjustment takes place in parallel with the intervention.

Task of the family doctor

Important in the care of bariatric patients is shared goal setting. First, it should be noted that as a primary care physician, it is not BMI that is treated, but the comorbidities of obesity. Then it is recommended to define together an approximate target weight. Here it is important to remain realistic. Normally, a weight reduction of around ten percent is already sufficient to slow down the development of secondary damage in the long term. In certain patients who are in psychosocially stressful situations, for example, even stopping weight gain can be considered a success. Accordingly, the therapy goals can be adapted to the individual needs of the patients.

When you ask obese patients if they want to lose weight, hardly anyone denies it. However, many patients need additional motivation to make the arduous journey out of metabolic syndrome. Left to their own devices, nearly 95 percent fail. Achieving the goal usually only succeeds through continuity. This does not have to be provided by the primary care physician alone. Continuity can also be provided by fitness coaching or nutrition counseling. As a primary care physician, you can show objectifiable progress with simple tools such as monitoring weight progress. When patients suggest jumping on fitness trends like the currently prevalent Intermittent Fasting, you should use that as well. The trend can be supplemented selectively with therapy suggestions from the GP side, if this seems to be more target-oriented. As with many chronic diseases, patience and understanding of the patient’s suffering is important. Even though weight reduction often presents itself as a Herculean task, it is possible.

Congress: WebUp

Literature:

- Monika Schmid (Oviva), Susanne Maurer, MD (adimed), Obesity Treatment in Family Practice, WebUp in Focus 02.05.2022.

- Swiss Health Observatory, https://ind.obsan.admin.ch/indicator/monam/uebergewicht-und-adipositas-alter-15, accessed 06/06/2022.

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH, www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/gesund-leben/gesundheitsfoerderung-und-praevention/koerpergewicht/uebergewicht-und-adipositas/kosten-uebergewicht-und-adipositas.html, accessed 06.06.2022.

- Quoted verbatim from: S. Maurer, Non-surgical therapy of obesity. Medinfo Publishing: The Informed Physician, 10-13 (2017).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(6): 41-42