Most hemangiomas do not require therapy due to their large regression potential. Up to an area of about 2× 2cm and a raised area of about 4 mm, electric cryotherapy at -32°C can be performed. Meanwhile, propranolol is considered in the guidelines as the first-choice therapy for complicated hemangiomas with a given indication. The response rate is 98%. Side effects of propranolol therapy are temporary, dose-dependent, and in the vast majority of cases harmless and reversible. Knowing the differential diagnoses of a hemangioma and creating a differentiated individual therapy concept is the real challenge so that ultimately an optimized treatment success and a high patient satisfaction can be achieved for the affected child. Diagnosis and therapy of vascular anomalies require interdisciplinary collaboration of specialized surgeons, pediatricians or dermatologists, as well as radiologists, angiologists, and possibly other disciplines.

Due to the high regression potential, most hemangiomas do not require therapy and it is sufficient to control them during their course. However, in the case of hemangiomas in functionally and aesthetically critical locations and with rapid size progression, early presentation to a specialist consultation and timely initiation of therapy are crucial. The aim of therapy is to stop growth and, if necessary, to initiate premature and rapid regression.

Cryotherapy

Up to an area of about 2× 2 cm and a loftiness of about 4 mm, electric cryotherapy can be performed at -32°C. The duration of a single session is about 8-15 seconds, depending on the localization and age of the infant. The procedure is not painful and repetition is possible. When used correctly, there is no fear of scarring. Sometimes small blisters or crusts are observed after treatment, which can be treated locally with a greasing wound ointment. The goal of therapy is growth arrest and, if necessary, involution induction.

Propranolol therapy

A chance discovery in a clinic in France in 2008 initiated a change in the treatment of hemangiomas. An infant received therapy with corticosteroids due to a facial hemangioma. A side effect of therapy was obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which necessitated therapy with a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol. Under this, there was a significant decrease in the hemangioma within a very short time. As a result, propranolol increasingly replaced the previous drugs, some of which had irreversible and severe side effects.

Previously used procedures such as cortisone therapy, interstitial laser therapy, surgical procedures, and the use of chemotherapeutic agents have become increasingly less important and are now only used in individual cases.

For some time, propranolol has been considered in the guidelines as first-line therapy for complicated hemangiomas with a given indication. In early 2014, approval was granted by the U.S. and European Medicines Agency and shortly thereafter by Swissmedic for an extemporaneous formulation and a branded propranolol solution for the treatment of complicated hemangiomas in infants.

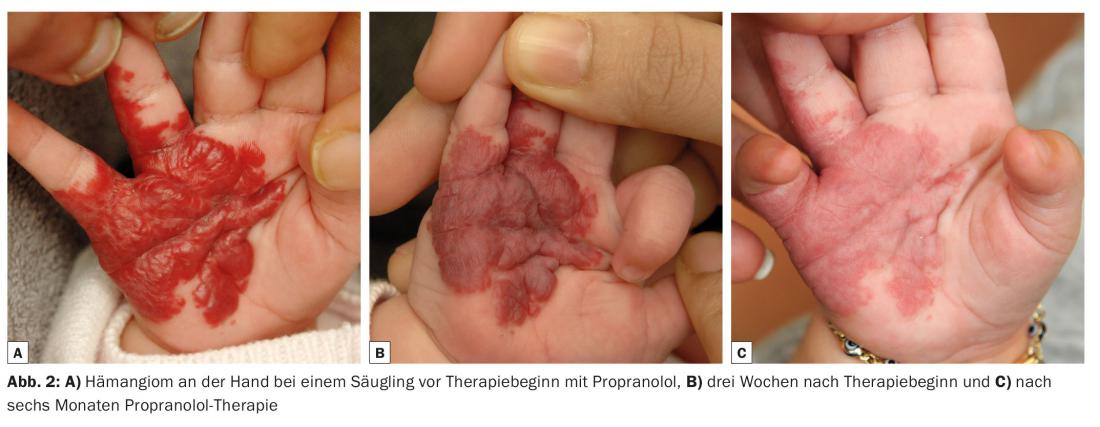

The response rate is 98%. Regression above 75% occurs in 81% of cases within 7.9 months (Figs. 1 and 2).

Side effects include cold hands and feet, sleep disturbances, nocturnal restlessness, diarrhea, and pulmonary symptoms. Bradycardia, hypoglycemia, or hypotension are observed in less than 1% of cases. Pyschomotor developmental disorders have not been demonstrated in studies. The side effects of propranolol therapy are temporary, dose-dependent, and in the vast majority of cases harmless and reversible.

A complete history and family history for congenital cardiovascular disease is required before initiating therapy. In addition to the clinical examination with special focus on cardiac auscultation, an ECG is performed. If the patient’s history or clinical examination is abnormal, further examinations may be necessary in advance. Propranolol is gradually phased in at 2 mg/kgKG/day divided into two to three single doses. Pulse monitoring, blood pressure and blood glucose checks should be performed during dose escalation. During subsequent follow-up visits, it is necessary to ask about possible side effects, check blood pressure and pulse, and adjust the dose depending on the current weight.

The duration of therapy is usually about six to nine months. If, in rare cases, the hemangioma regrows after the end of therapy, propranolol can be given again without any problems, usually for a period of two to three months. It is not necessary to phase out the therapy.

Topical beta blocker therapy

For a few years now, in addition to systemic beta-blocker therapy, there has also been the possibility of topical application. In the guidelines for hemangioma therapy, the recommendation in this regard is still very cautious. This is because there has been only one controlled study of topical use of beta-blockers in infantile hemangiomas.

In the study, timolol gel 0.5% showed a significant size decrease from week 20 and a significant color difference from week 24 compared to placebo. No difference in heart rate and blood pressure was observed. The effect in terms of volume, growth and appearance occurred significantly later and more slowly than with oral propranolol therapy.

Furthermore, there are insufficient pharmacological data on penetration, absorption and systemic effects. The bioavailability of timolol when absorbed through intact skin is not known. Increased uptake is to be assumed especially in ulcerations and in hemangiomas in the vicinity of the mucosa. However, only one patient has been described in the literature to date in the use of a topical beta-blocker for a hemangioma with an adverse reaction in terms of sleep disturbance.

Residuals

After the regression phase, interfering residuals may be observed in a few individual cases. In these cases, surgical resection or dye-pulsed laser therapy is an option. It is recommended to remove the residuals before school entry or in adolescence, because on the one hand a large part of the involution has already taken place and on the other hand the children can share and support the decision about the intervention.

The differential diagnosis is a challenge

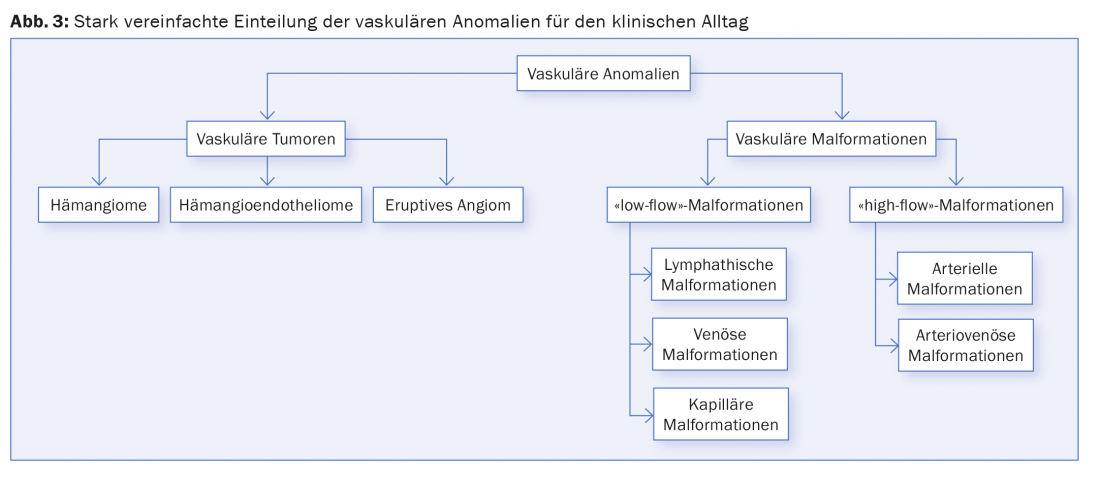

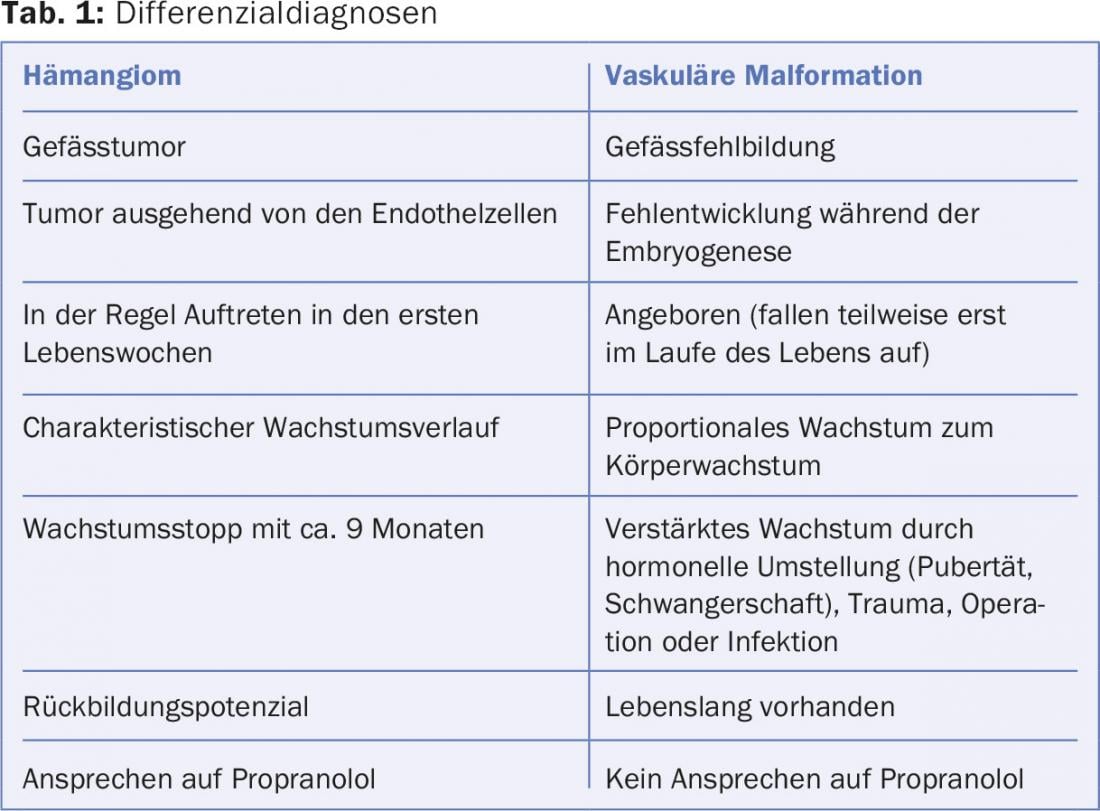

Hemangiomas belong to the complex of vascular anomalies along with other clinical pictures (Fig. 3) .

Their differentiation from other vascular tumors and the vascular malformations is not always easy. However, confusion or lack of knowledge can have fatal consequences for the children concerned. Even a targeted history, the course and the clinic can be helpful and goal-directing (Tab. 1). Another challenge is the differentiation of vascular malformations from each other. Here, too, a detailed medical history is absolutely necessary. Additional diagnostics such as Doppler sonography and/or time-resolved MR angiography usually allow a clear diagnosis.

Vascular tumors

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: Hemangioendothelioma is a vascular tumor that usually occurs within the first year of life. It grows slowly and infiltrates and has a dermal palpation. A complication that may occur is Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (disseminated intravascular consumption coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia). Treatment options differ based on localization and size. Mainly surgical resection or therapy with chemotherapeutic agents is performed. Therapy with propranolol may be attempted.

Eruptive angioma: Eruptive angiomas (also called granuloma pyogenicum) sometimes develop in young children after minor trauma. They appear as a pedunculated, spherical, angiomatous mass (Fig. 4) . Recurrent bleeding and size progression occur, which is why the treatment of choice is removal of the angioma under short anesthesia.

Vascular malformations

Vascular malformations are congenital vascular malformations, which sometimes only become apparent during the course of life, e.g. in the case of increased growth during hormonal stimulation phases such as puberty, pregnancy, as well as through infections, traumas or operations. Otherwise, they grow proportionally to the growth of the body. Clinically/diagnostically, they are differentiated by the velocity of blood flow in the findings into “low-flow” (venous, capillary, and lymphatic) and “high-flow” (arterial, arterio-venous) malformations. They usually occur sporadically and unifocally, and in less than 1% of cases they are multifocally localized.

Capillary malformation: A reddish discoloration of the neck or upper eyelids and forehead is frequently observed in infants (Fig. 5) . Also known as “stork’s bite” or “angel’s kiss” in the population, this is a nevus flammeus neonatorum which completely regresses within the first years of life. In addition, there is the classic “fire mole”, the nevus flammeus, which becomes darker due to capillary dilatation in the course of life. It may be associated with syndromal disease and co-occur with other vascular abnormalities. For example, in Sturge-Weber syndrome with capillary malformation in the area of the first trigeminal branch or in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, where capillary, lymphatic, and venous malformation occurs in one limb along with hypo- or hypertrophy of the affected limb. If an arteriovenous malformation is present, it is called Parks-Weber syndrome.

In the case of a singularly occurring nevus flammeus, dye-pulsed laser therapy can be performed for aesthetic reasons.

Lymphatic malformation: Lymphatic malformations present as a soft swelling. Therapy of choice is surgical resection. If this is not possible due to size or aesthetics, sclerotherapy with OK432, an attenuated pathogen of the Streptococcus pyogenes type, can be performed. Recurrences are unfortunately common. A new therapeutic approach is the administration of sildenafil. Unfortunately, the success is not as pervasive as propranolol for hemangiomas.

Arterial and arteriovenous malformation: this type of vascular malformation is primarily found intracerebrally. If they occur outside, pulsation can sometimes be felt. Complications are frequent and more severe. Pain (including at night), local ischemia, spontaneous spurting hemorrhage, and heart failure occur with large shunt volumes. Unlike hemangiomas, they show infiltrative growth similar to that of a malignant tumor. Therapeutically, resection and/or embolization via the inguinal artery can be performed.

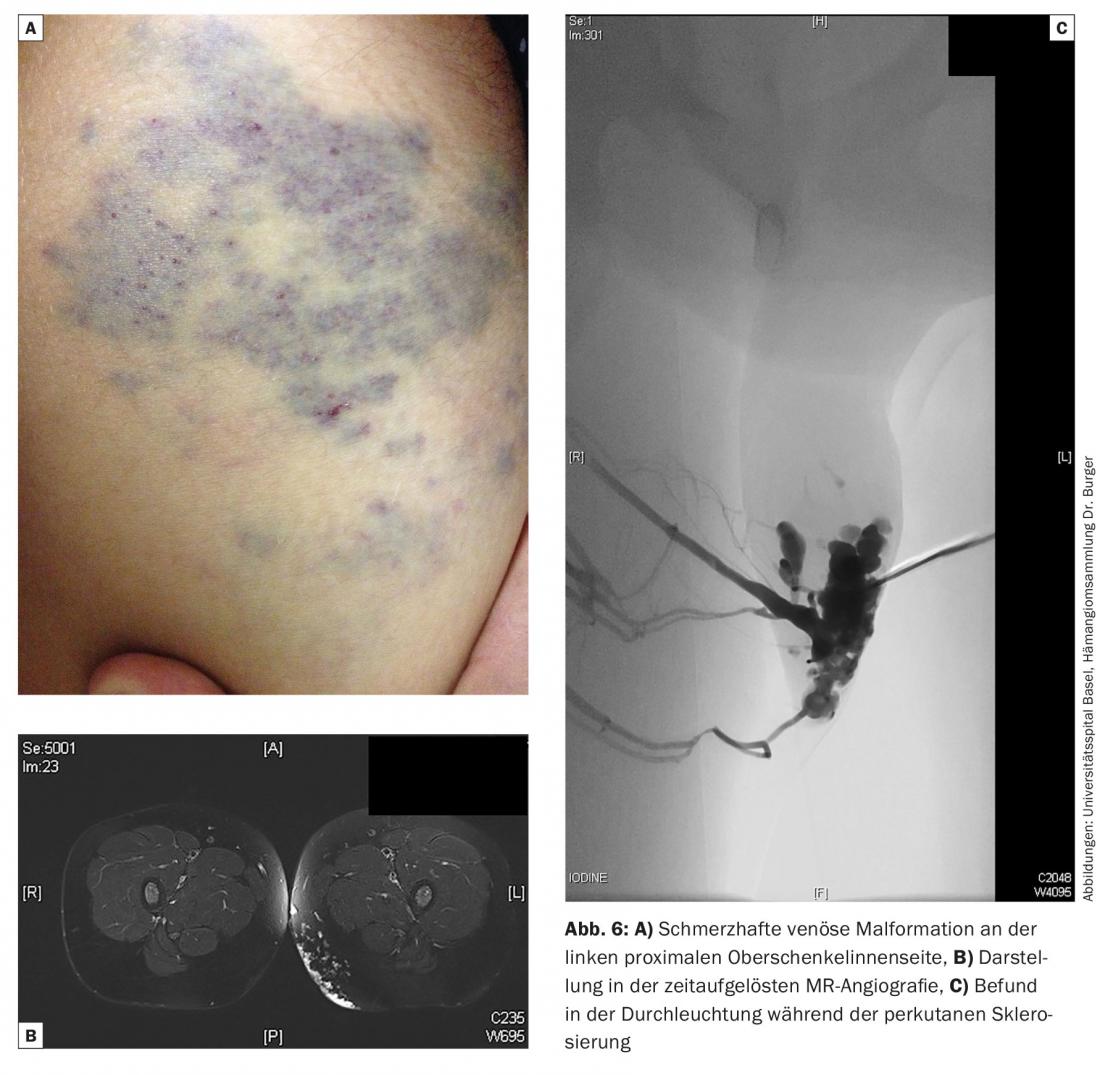

Venous malformation: Clinically, a soft, bluish shimmering, compressible swelling is found in venous malformations. Characteristically, there is an increase in findings with exertion, hanging of the affected body part, and warm showering/bathing. Occurring pain increases during the day and decreases at night. Painful thrombophlebitis may occur as a complication. Venous malformations make up the most common type of malformation, accounting for approximately two-thirds. Symptomatic therapy with NSAIDs and compression (compression stockings class II) can be performed. If thrombosis or thrombophlebitis occurs, a s.c. injection therapy with a low molecular weight heparin (100 anti-Xa IU/kgKG/d) for approx. 20 days can help. Complete surgical resection may be considered as causal therapy. If complete surgical resection cannot be performed, percutaneous sclerotherapy with ethoxysclerol foam or sclerogel should be performed. This may require several sessions (Fig. 6).

Further reading:

- Hemangiomas in infancy and early childhood. Guideline of the German Society for Pediatric Surgery, the German Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, the German Dermatological Society, the Working Group for Pediatric Dermatology and the German Society for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. AWMF Guideline Register No. 006/100, as of 02/2015.

- Schupp CJ, et al: Propranolol therapy in 55 infants with infantile hemangioma: dosage, duration, adverse effects, and outcome. Pediatr Dermatol 2011; 28(6): 640-644.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, et al: Propranolol for severe haemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med 2008; 358 (24): 2649-2651.

- Marqueling AL, et al: Propranolol and infantile hemangiomas four years later: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30(2): 182-191.

- Hogeling M, et al: A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2011; 128(2): 259-266.

- Leaure-Labreze C, et al: Infantile hemangiomas: the revolution of beta-blockers. Rev Prat 2014; 64(10): 1421-1428.

- Chan H, et al: RCT of timolol maleate gel for superficial infantile hemangiomas in 5- to 24-week-olds. Pediatrics 2013; 131(6): 1739-1747.