A lot has happened since the first tissue transplant. Not only that complete organs are now being transplanted. The transplantation was also put on legal footing.

The donation and transplantation of organs, tissues and cells has only been regulated at national level in Switzerland since 2007 – by the Transplantation Act and the Transplantation Ordinance [1,2]. But what are the legal aspects regarding donation as well as allocation of organs from deceased donors in detail, what criteria are used and what adjustments have been made over time?

The basic principle of legislation in the allocation of organs is formulated in Art. 17 of the Law on Transplantation: No one may be discriminated against in the allocation of an organ. Since 2007, this has been carried out by the Swisstransplant National Allocation Office according to the criteria of medical urgency, medical benefit, equal opportunity and waiting time. The formulation of these criteria varies depending on the organ and is set out in detail by the legislator in two further ordinance levels, the Organ Allocation Ordinance and the Organ Allocation Ordinance of the Federal Department of Home Affairs (FDHA) [3,4].

On the donor side, extended explicit consent currently applies. The basic principle is formulated in Art. 8 of the Transplantation Law: organs may be removed from a deceased person only if he or she has consented to removal (and death has been established) before his or her death. If there is no documented consent or refusal, the next of kin should be asked if they are aware of a declaration of donation. This request can be made only after a decision has been made to discontinue life-sustaining measures. If no such declaration is known from the deceased person, organs can only be removed if the next of kin consent to removal. In making their decision, these must take into account the presumed will of the deceased person. If there are no next of kin or they are not available, the removal is not permitted. The will of the deceased person always takes precedence over that of the next of kin [1].

However, documented consent or refusal (usually in the form of an organ donor card or living will) is rarely found in practice. According to unpublished data from Swisstransplant, this was the case in only 19% of all individuals considered for donation in 2017. This means that in over 80% of the conversations with relatives, the will of the deceased person is either not documented or completely unknown. Swisstransplant assumes that this is one of the reasons why the consent rate for discussions with relatives in Switzerland is very low. The 40% surveyed in 2017 is just about half the level of agreement that respondents report for themselves in surveys [5]. Swisstransplant has therefore developed an electronic register in which everyone can document their will regarding organ and tissue donation. The national organ donor registry has been online since October 1, 2018, and all hospitals can check with Swisstransplant if a potential donor has an entry. April 2019, around 55,000 people have already registered.

In addition, Swisstransplant supports a popular initiative that would like to introduce the so-called extended contradiction solution (also “presumed consent”) in place of the current extended explicit consent regulation. In the case of presumed consent, the organs of a deceased person may be removed if the deceased person did not object during his or her lifetime and the relatives also have no knowledge that the deceased person would not have wanted to donate. The relatives will therefore also be involved in the contradiction solution – in contrast to today, however, they would no longer have to decide on organ donation on behalf of the donor. Swisstransplant is convinced that this would relieve both the relatives and the medical professionals in a difficult situation and increase the rate of consent during discussions with relatives. What many do not know: By the time the national legislation came into force, 17 of 26 cantons already knew the extended contradiction solution [6]. The “Promote Organ Donation – Save Lives” initiative was formally submitted in the spring of 2019.

Organization of organ donation and transplantation

The six Swiss transplant centers are located at the five university hospitals in Basel, Bern, Geneva, Lausanne and Zurich, as well as at the Cantonal Hospital in St. Gallen. Each center focuses on transplantation of specific organs. Hospitals require a permit from the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) for each transplant program (Fig. 1).

The donation process has also been nationally regulated since 2007 and is now organized on three levels. At the national level, Swisstransplant is mandated by the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Health (GDK) to coordinate the tasks of the cantons as laid down in the Transplantation Act throughout Switzerland, to establish national standards and to exploit synergies. On behalf of the FOPH and the cantons, Swisstransplant also supports hospitals in the identification, notification and medical clarification of potential organ donors [7].

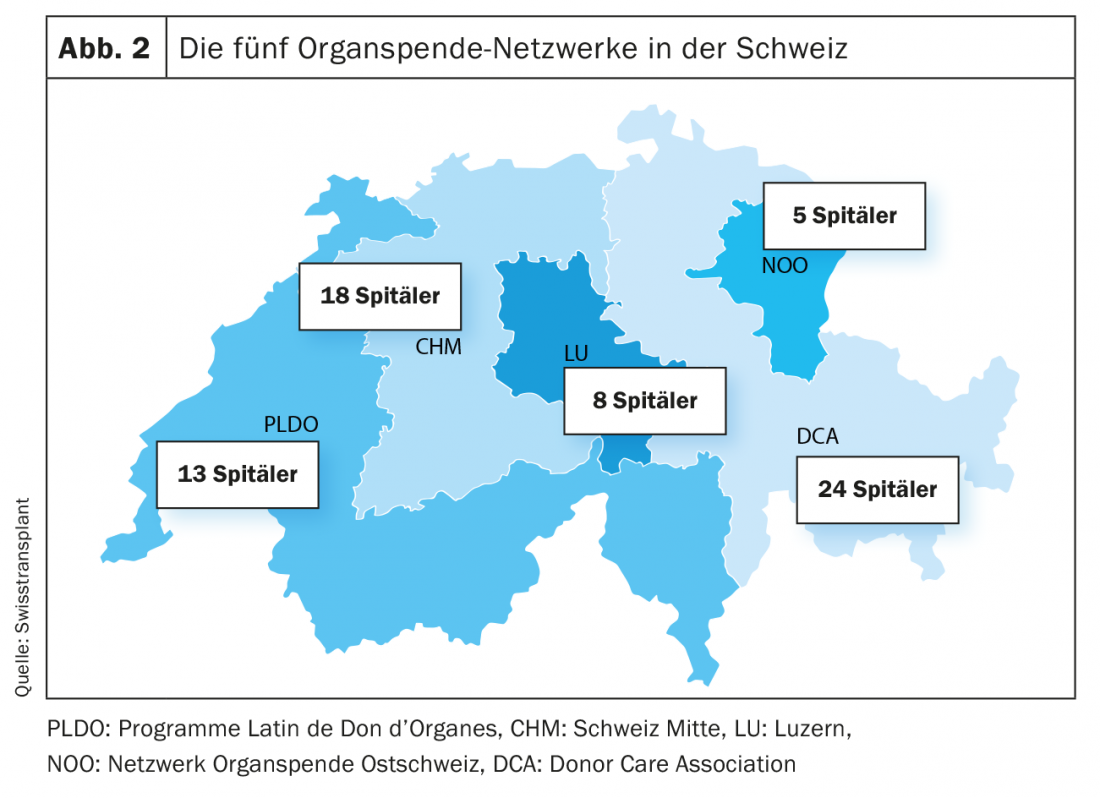

At the regional level, there are now five so-called organ donation networks (Fig. 2). These support the hospitals within their network in identifying potential donors, providing them with medical care, and supporting their families and relatives. Another important task of the organ donation networks is the education and training of the professional staff in the hospitals [7].

Allocation of organs

In order for a patient to be allocated a donor organ, she or he must be on the national waiting list for that organ. The requirements for admission and remaining on the waiting list (medical indication, no permanent contraindication, no other medical reasons jeopardizing the success of transplantation) are regulated in Article 3 of the Allocation Regulation. In addition, written informed consent must be obtained from the patient [3].

The Swisstransplant National Allocation Center maintains the waiting list. Hospitals and transplant centers report to Swisstransplant every deceased person who meets the requirements for organ donation, including all data required for allocation. Swisstransplant uses the donor data, the data of patients on the waiting list and the allocation criteria to determine the possible recipients for each organ and establishes a ranking among them. The criteria needed to create the ranking list are stored as algorithms in database software specially developed for this purpose. The so-called Swiss Organ Allocation System (SOAS) supports the Foundation and enables a rapid and legally compliant allocation of all organs throughout Switzerland. Swisstransplant allocates the organ to the patient with the highest priority and the responsible transplant center must then evaluate the organ offer within a 60-minute time window. If the transplant center cannot perform the transplant or rejects the donor organ, Swisstransplant allocates the organ to the patient with the next highest priority [3].

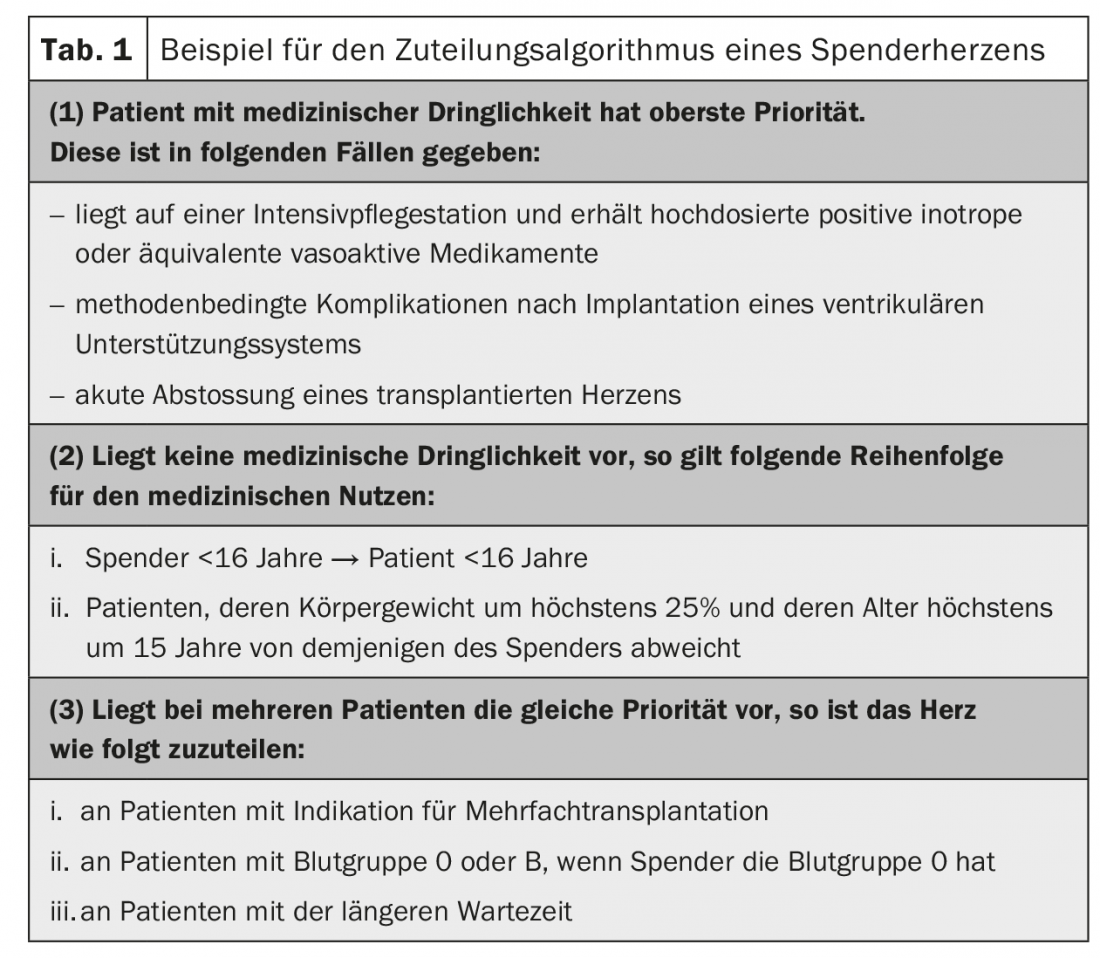

The allocation criteria and priorities are set out in detail in the Allocation Ordinance FDHA: For each organ, the medical urgency is defined, the order of medical benefit as well as other criteria to determine the order. The latter are used when multiple recipients meet medical urgency status or the same medical benefit has been calculated for multiple patients (Table 1).

Continuous review and adjustment of the allocation criteria

Compliance with the principles of organ allocation is periodically monitored, in particular whether they meet the requirement of fair allocation. Adjustments may be proposed to the FOPH as needed. Regular evaluation of the allocation criteria is very important because it allows medical developments and technical advances to be reflected promptly in the legislation and applied in practice. The evaluation of the allocation criteria is performed by the Comité Médical (CM), a Swisstransplant medical committee in which all transplant centers, the national reference laboratory for tissue characteristics and the National Allocation Center are represented. To this end, the CM establishes standing working groups of medical experts in individual organs or other specialties to advise the CM.

As of June 1, 2015, for example, at the request of the Swisstransplant Liver Working Group (STAL), the liver allocation criteria were adjusted to allow liver split transplantation, particularly for children. For adult livers, there is a possibility that the left liver lobe will be used for a child (<25kg) and the right, larger liver lobe will be used for an adult recipient. Both lobes of the liver have the ability to continue to grow in the recipient. Prerequisites for liver splitting are sufficiently good quality, i.e. minimal steatosis, good liver values especially with regard to the kinetic indicator reaction and no underlying diseases. With the adjusted regulation, unless there are patients with medical urgency on the waiting list, livers from donors between the ages of 18 and 49 must be allocated first to patients weighing up to 25 kilograms. This adjustment was essential to improve the situation of children on the waiting list without simultaneously discriminating against adult recipients [8].

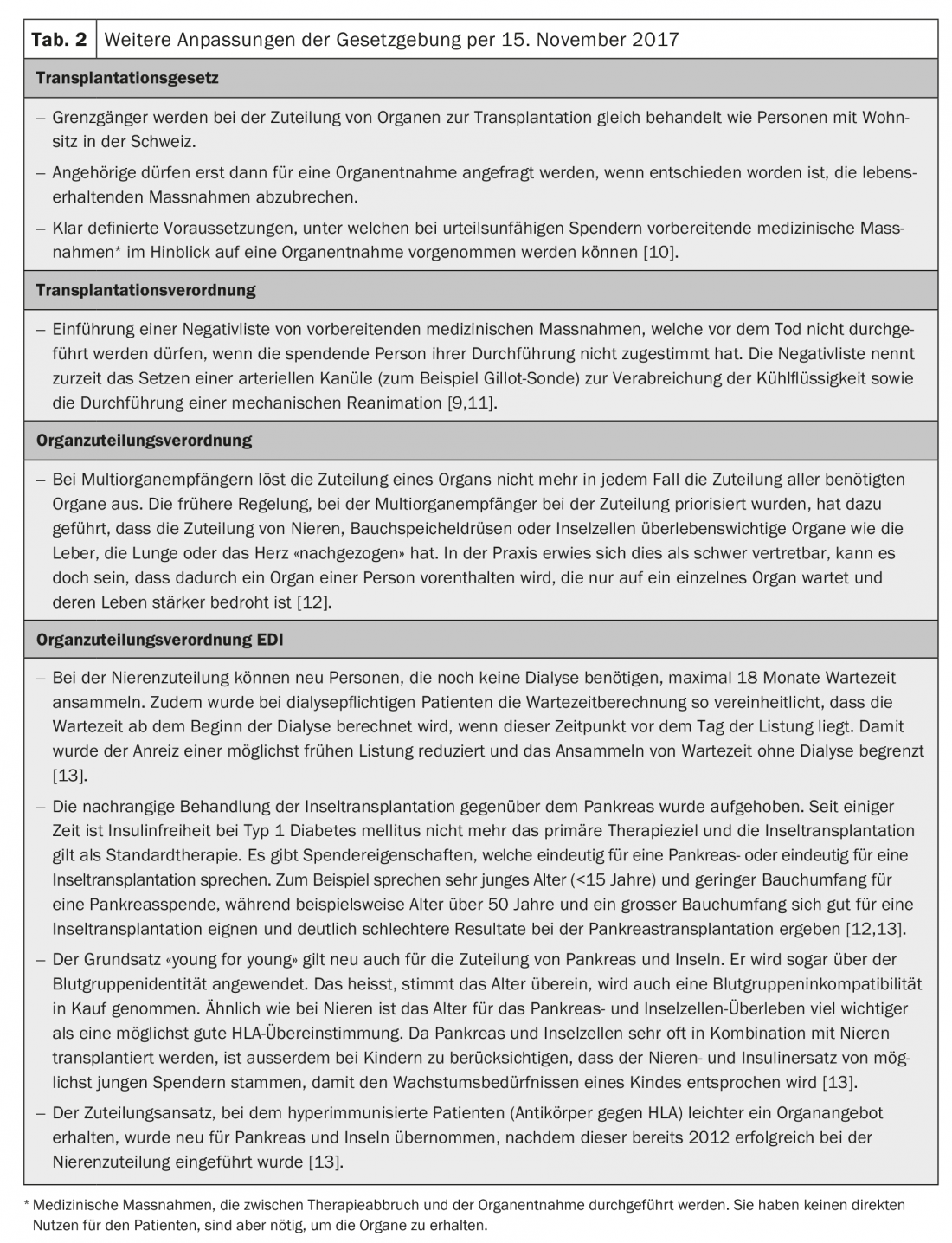

As of November 15, 2017, the Transplantation Act has been partially revised and adjustments have been made to all ordinances. An important change, which has been in force since then, concerns the organs of donors who have previously been successfully treated with “direct acting anti-viral agents” (DAAs) against hepatitis C and no longer show any detectable viremia. Based on a request from Swisstransplant, these organs may now also be transplanted to recipients who are not infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). The prerequisite for this is, on the one hand, a non-reactive HCV nucleic acid test (HCV-NAT-) in the donor (whereby the test result for hepatitis C antibodies is no longer relevant) and, on the other hand, a signed consent from the recipient (informed consent). The same applies to organs from donors in whom spontaneous recovery has been demonstrated [9].

In life-saving situations, transplantation of organs from HCV-NAT+ individuals to recipients in whom the virus has not been detected has also been allowed since November 15, 2017. In this case, of course, the risk of HCV transmission is very high. However, it is assumed that hepatitis C is now a well-curable disease thanks to the new therapeutic options with DAAs and that, against this background, HCV transmission can be accepted in life-saving situations [9]. Table 2 provides a brief overview of the other changes as of November 15, 2017.

Equal opportunities through uniform conditions

With the entry into force of national legislation in 2007, much has changed for the better in the organ donation and transplantation landscape in Switzerland. For the first time, a uniform framework was created for all transplant centers, and since then the same allocation criteria have applied to all patients on the waiting list. The fundamental principle of equal opportunity for all patients has been strengthened and enshrined at the national level.

In ten years since the national legislation came into force, the lowest ordinance level alone, in which the allocation rules are set out in detail for each institution, has already been amended seven times. This shows that the supervisory function is performed by the Swisstransplant working groups and that in the field of organ transplantation the legal basis is adapted comparatively quickly to new findings and medical progress.

However, with national legislation, the overall organ donation side has also gained significantly more weight. The law was drafted with foresight, recognizing that it was necessary not only to regulate organ allocation but also to address the availability of organs for transplantation. This subsequently enabled the establishment of today’s nationwide network structure, the establishment of national specialist training for medical staff and created the conditions for standardized and optimized work processes and quality controls. This is the case, for example, with the identification and notification of potential organ donors, the medical treatment of donors or the care of their relatives. Even if the standardization of workflows and documents in a traditionally federally organized system is a Herculean task that will continue to occupy Swisstransplant in the future, national legislation has clearly led to a professionalization on the organ donation side as well, which can be substantiated with figures. From 2008 to 2017, the annual number of organ donors increased from 91 to 145 (+59%). The reintroduction of donation after death following sustained cardiovascular arrest in 2011, which already accounted for 27% of all donors in 2017, also contributed to this [14].

Literature:

- The Federal Assembly of the Swiss Confederation: Federal Law on the Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells, 810.21, July 1, 2007.

- The Swiss Federal Council: Ordinance on the Transplantation of Human Organs, Tissues and Cells, 810.211, 1. July 2007.

- The Swiss Federal Council: Ordinance on the Allocation of Organs for Transplantation, 810.212.4, July 1, 2007.

- The Federal Department of the Interior. Ordinance of the FDHA on the Allocation of Organs for Transplantation, 810.212.41, 1. July 2007.

- Weiss J, et al: Attitudes towards organ donation and relation to wish to donate posthumously. Swiss Med Wkly 2017; 147: w14401.

- Weiss J, Immer FF: Organ donation in Switzerland – explicit or presumed consent? Schweiz Ärzteztg 2018; 99(5): 137-139.

- Swisstransplant: Annual Report 2017. National Foundation for Organ Donation and Transplantation, Bern, 2018.

- Always FF: Legal aspects of organ allocation – light and shadow. Schweiz Ärzteztg 2015; 96(48): 1780-1782.

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Explanatory Report on the Amendment of the Transplantation Ordinance of 18.10.2017. Legislative projects in transplant medicine/revision of the transplant ordinance.

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Revision of the Transplantation Act. Legislative projects in transplant medicine. Cited November 5, 2018.

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS): Determination of death with regard to organ transplantation and preparation for organ removal 2017.

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Explanatory Report on the Amendment to the Organ Allocation Ordinance of 18.10.2017. Legislative projects in transplant medicine/revision of the Organ Allocation Ordinance.

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Explanatory Report on the Amendment to the Organ Allocation Ordinance FDHA of 19.10.2017. Legislative projects in transplant medicine/revision of the organ allocation ordinance FDHA.

- Weiss J, et al: Deceased organ donation activity and efficiency in Switzerland between 2008 and 2017: achievements and future challenges. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18(1).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(7): 12-16