This year’s congress of the Swiss Society of Dermatology and Venereology (SGDV) took place in Geneva at the end of August. Apart from the key lectures on important topics and the poster exhibition, the case presentations of the dermatological university clinics were particularly interesting – not only patients were presented, but also diagnostic algorithms and therapy guidelines.

The staff of the Dermatology Clinic at the University Hospital Basel focused their case presentations on lesions of the oral mucosa.

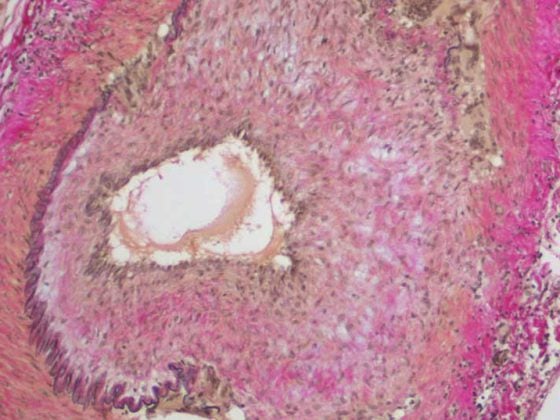

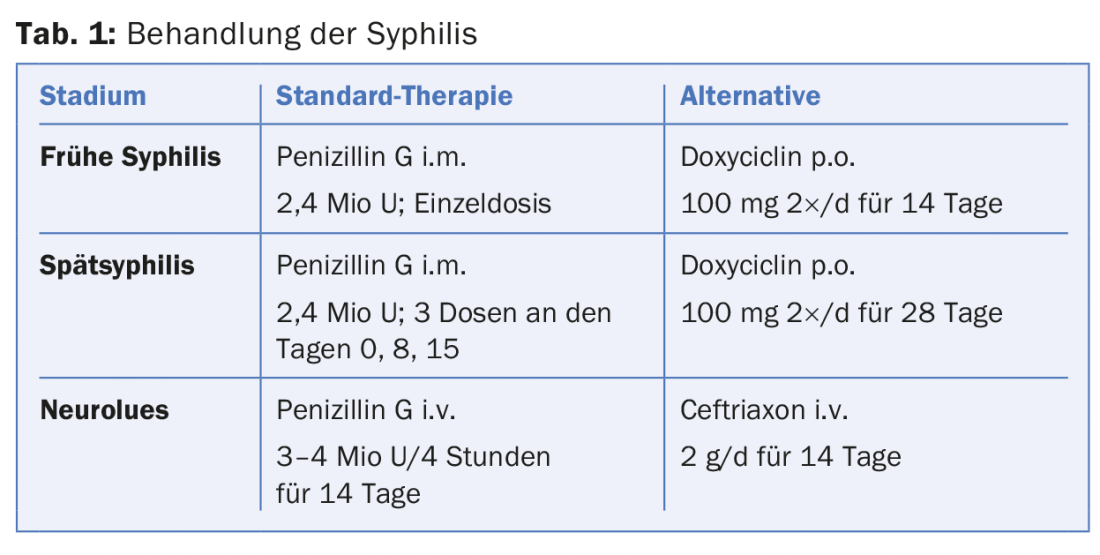

An important differential diagnosis in oral ulcerations is syphilis: 12-14% of all patients with stage I syphilis present with intraoral or perioral ulcers. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are particularly at risk: 54% of patients with syphilis are MSM. If syphilis is diagnosed early, treatment is usually simple (tab. 1). It is important to additionally search for other sexually transmitted diseases, especially HIV.

Candida stomatitis – a chameleon

Oral candiasis is a true chameleon, as lesions may present with white coatings or reddened mucosa, atrophic or inflamed, acute or chronic:

- White candiasis: acute pseudomembranous or chronic hyperplastic (leukoplakia);

- Erythematous candiasis: atrophic redness (burning pain, common in denture wearers), median rhomboid glossitis, angular cheilitis, gingival erythema (common in HIV patients).

In immunocompetent patients, therapy consists of administration of 100-200 mg/d fluconazole for 7-14 days; “single-shot” is no longer practiced. If fluconazole-resistant germs exist, give 100-200 mg/d itraconazole for up to 28 days, plus posaconazole suspension.

Aphthae – harmless or tip of an iceberg?

Aphthae are common lesions of the oral mucosa, but they bring few patients to the doctor. However, recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) can be very troublesome, especially if the aphthae occur several times a month or if there is complex aphthosis (more than three aphthae at the same time). Aphthae are thought to occur because of local immune system dysfunction, triggered by infection, mechanical trauma, hypersensitivity to certain foods, hormonal fluctuations, vitamin or mineral deficiencies, stress, or genetic factors.

Aphthae are also the most common symptom of Behçet’s disease: Aphthae occur as the first symptom in 89% of patients; genital ulcers (14.2%), erythema nodosum (5.7%), and ocular involvement (4.2%) are much less common.

In patients with recurrent aphthae, the first step is to rule out an underlying disease (HIV, inflammatory bowel disease, neutropenia, malnutrition, etc.). Once the diagnosis of RAS has been established, there are various treatment options with different levels of evidence (Tab. 2). First of all, it is important to inform and educate the patient to avoid possible triggers for the aphthae. Local steroids, possibly systemic steroids for a few days to weeks, usually help.

The presenters also advocated a trial of therapy with colchicine: starting with 0.5 mg/d, + 0.5 mg/d every two weeks until dosing of 3× 0.5 mg/d. Blood counts are checked biweekly for the first six weeks, and every three months thereafter. Particular attention must be paid to any renal insufficiency and to interactions with CYP3A4 inhibitors. Signs of intoxication are nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Small pores – big effect

Prof. Yogehavar N. Kalia from the Institute of Pharmacy at the University of Geneva is working on the topical therapies of the future, among other topics. He reported on his current research at the SGDV Congress in a Key Lecture.

The skin forms a very effective protection from the environment, but also keeps therapeutic agents from penetrating. Only lipophilic substances can penetrate the skin. However, the lipophilicity of different active ingredients differs greatly. And the penetration of a drug into the skin does not guarantee that it will reach its destination if, for example, it gets “stuck” in the uppermost layers of the skin. Various strategies have been developed to overcome the skin barrier function: Optimization of the galenic form, application of energy (iontopheresis, photomechanical waves, etc.) and also mechanical as well as physical minimally invasive techniques (microneedles, lasers, thermal applications).

Prof. Kalia’s research group is investigating new technologies that reversibly lower the skin barrier so that molecules that previously could not be applied through the skin can be administered transdermally. One of these technologies is P.L.E.A.S.E.® (Painless Laser Epidermal System). This system uses an Er:YAG laser that creates microchannels (pores) in the stratum corneum by vaporizing water molecules. The more of these pores there are and the deeper they are, the greater the absorption of the active ingredient.

Source: 98th Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Dermatology and Venereology (SGDV), August 25-27, 2016, Geneva.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(5): 34-35