In some patients, chronicizing symptoms develop after the acute phase of Covid-19 infection. In the S1 guidelines on Long-Covid published by various professional societies, this is highlighted from an interdisciplinary perspective. Covid-associated skin changes or hair loss are self-limiting according to the current state of knowledge; symptom-targeted therapy is advised if the patient suffers from the condition.

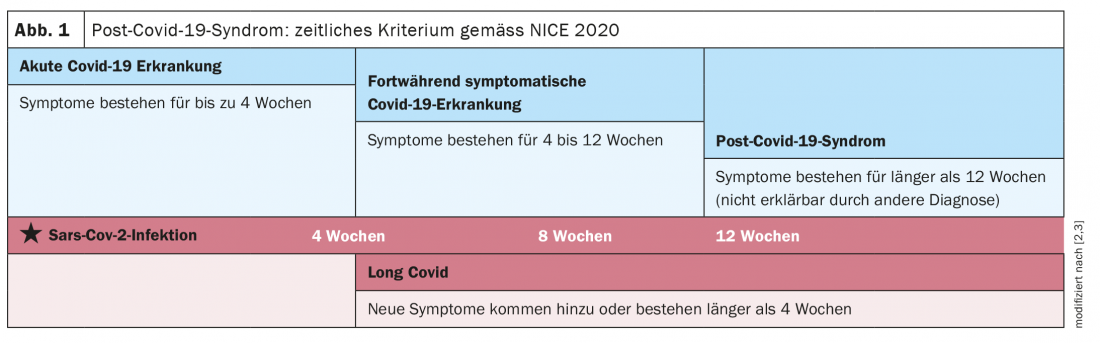

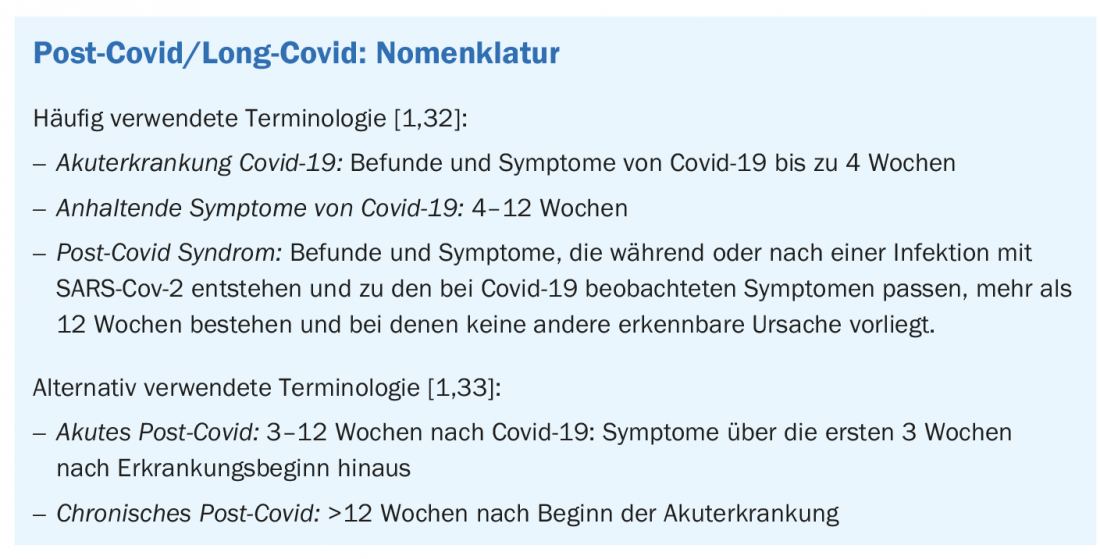

Long covid/post covid is still a young disease or complaint, the classification of which is in a dynamic stage [1]. In the English-language literature, the terms “post-acute sequelae of Covid-19,” “chronic covid syndrome,” or “Covid-19 long-hauler” are also commonly used. In the S1 guideline by Koczulla et al. 2021 Long-Covid/Post-Covid is defined as follows: “The diseases with the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) are called Covid-19. This particularly affects the lungs, but other organs may also be affected. In approximately 10% of those affected, symptoms last longer than four weeks. This condition is called long covid or post covid. Whether long/post covid syndrome is a disease in its own right is still unknown” [2]. The temporal criterion is the presence of symptoms beyond 4 weeks after the onset of disease (box, Fig. 1) [1,3]. Different organ systems may be affected. Causes of the subacute and chronic manifestations are still unclear. Various mechanisms, such as functional limitations of multiple organ systems due to tissue damage, as well as postviral autoimmunity, are discussed [5]. Data on the incidence of long-covid problems vary in the literature depending on the data source or the particular study population examined (e.g., previously hospitalized, non-hospitalized, and mixed samples) [1]. That younger patients with mild disease can also be affected is shown by a web-based survey study in which more than half of 30-60-year-old respondents with low-risk factors had persistent covid symptoms four months after suspected or proven covid 19 disease, which included signs of damage to multiple organs [7,8].

Covid-associated skin manifestations have attracted a great deal of interest, according to a Google Trends analysis. According to the guideline by Koczulla et al. up to a quarter of patients report skin changes after having undergone Covid-19 infection [2,9–12].

What is known about skin changes after Covid infection?

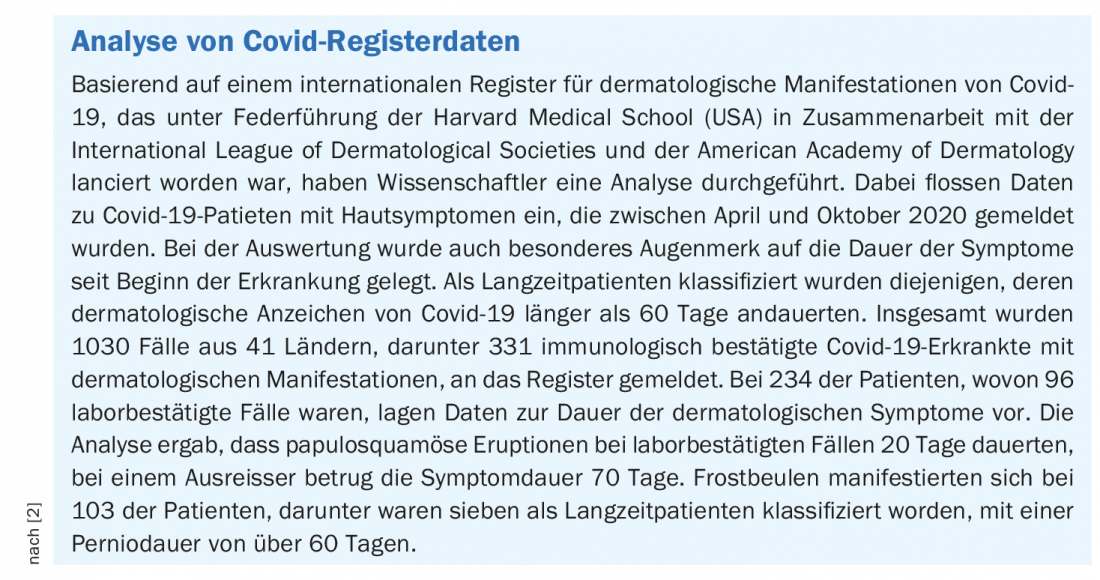

The spectrum of symptoms is relatively heterogeneous, ranging from maculopapular and livedo reticularis/racemosa-like skin lesions to urticarial and erythema multiforme-like to varicelliform skin lesions [2]. So-called covid toes have also been observed, which occur mainly in younger and barely symptomatic patients. These are bluish, cushion-like thickenings over the small joints of the toes and fingers that look very similar to a Pernio or Chilblain lesion, but are often asymmetric and sharply demarcated, and local detection of SARS-CoV-2 is often unsuccessful [13,14]. From an analysis of a US registry of dermatologic manifestations of Covid-19 , pernio lesions persisted for more than 60 days in 7 of 103 patients with frostbite (box) [15]. In addition, increased hair loss extending for weeks to months after infection is reported in up to 25% of cases [17]. Occasionally, hyperesthesia as well as rhagades and exsiccosis of the hands (in the sense of toxic hand eczema) were observed [18,19].

What should be considered with regard to diagnostics?

If a Covid-19-associated skin disorder is suspected, the first step is to detect an acute or a recent infection. However, a negative result does not preclude an association. In addition to SARS-CoV-2, it is reasonable to rule out drug-induced genesis [20,21]. Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that there is an exacerbating correlation between Covid-19 and chronic inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus, which are characterized by pro-inflammatory cytokines and autoimmune responses [10]. Especially in patients with immunosuppressive treatment, specialist dermatological and, if necessary, rheumatological clarification is recommended [22–24].

What do the pathophysiological concepts say?

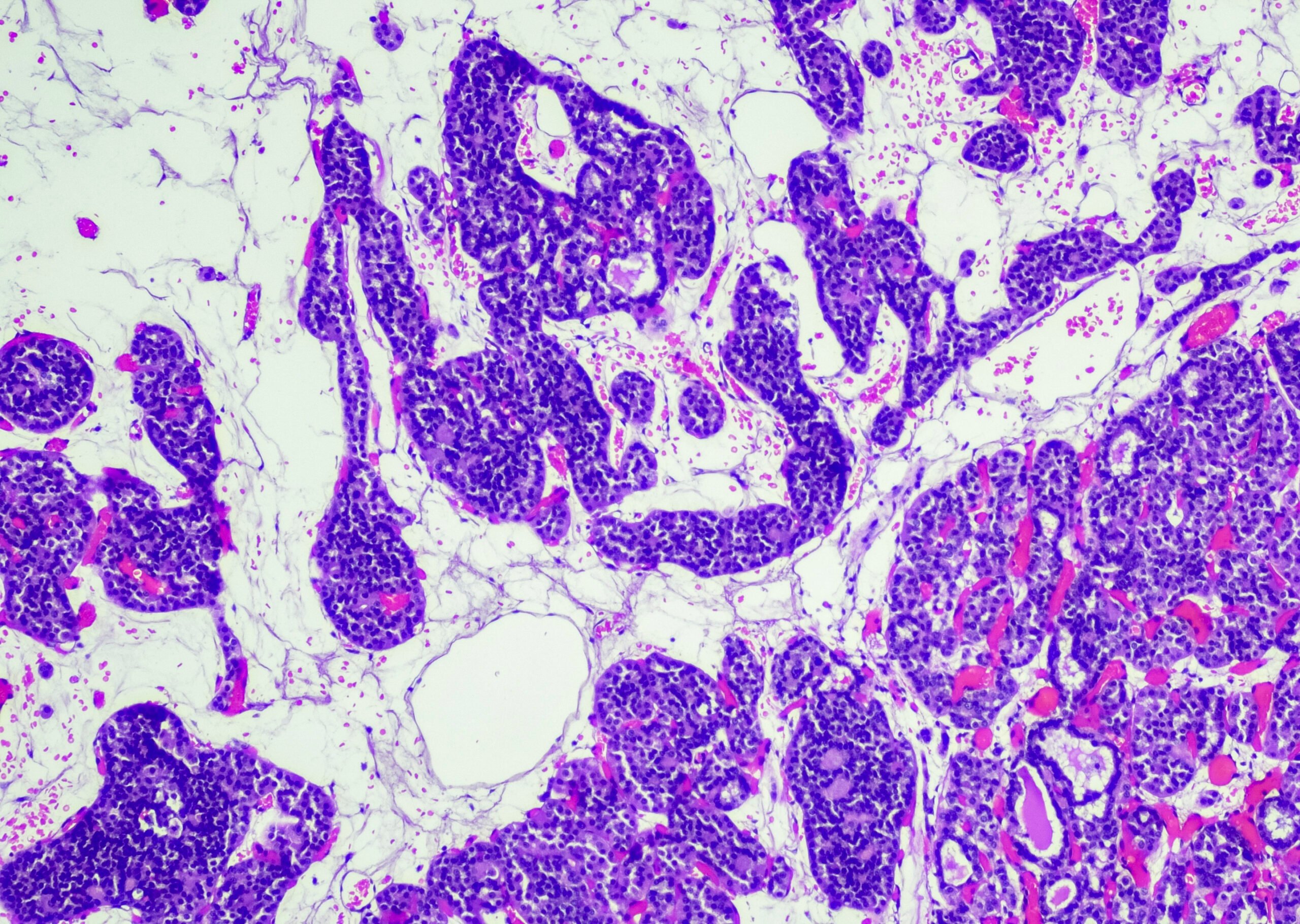

Analogous to autoimmune diseases, Long-Covid is thought to involve T- and B-cell dysregulation [1]. Histologically, there is partial evidence of thromboembolic/thrombotic events in small skin vessels, presumably underlying viral-loaded antigen-antibody immune complexes (e.g., perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates or intradermal edema) [11,25–28]. As the disease progresses, fibrosing transformation of the dermal tissue may develop [29]. Acetylcholinesterase 2 (ACE2) is expressed by epidermal and follicular keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells in skin and expression correlates with inflammatory parameters such as natural killer cells, cytotoxic T cells and B cells [30]. Regarding livedo reticularis/racemosa and vasculitis, a relationship with hypercoagulability status is suspected in Covid-19 [16].

Symptom-guided treatment recommended

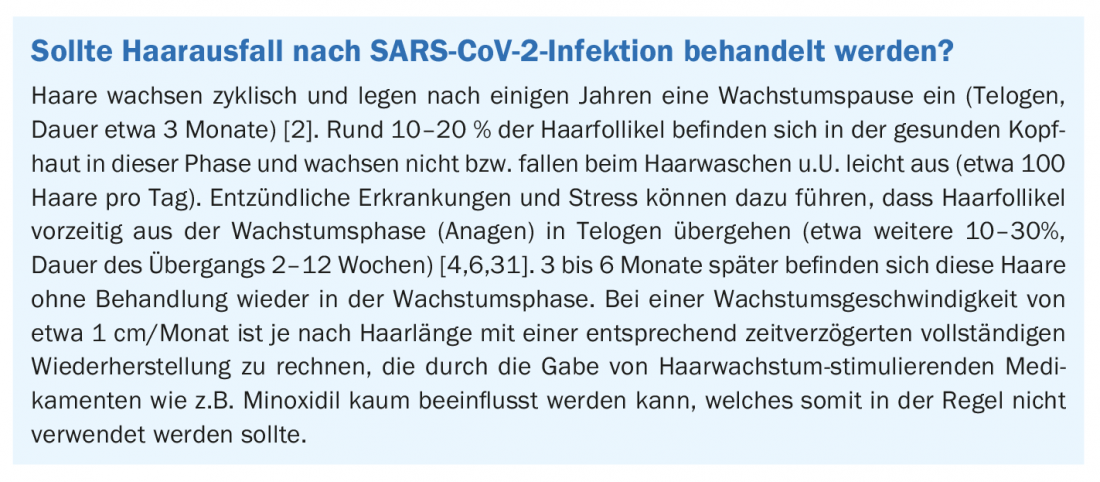

In the S1 guideline by Koczulla et al. it is pointed out that most skin lesions described in connection with Covid-19 heal spontaneously and without specific treatment in a few weeks [2]. In patients with a condition requiring treatment, such as excruciating itching or disfiguring lesions, symptom-directed treatment is advised. For this purpose, for example, antihistamines or cooling and covering externals as well as lesional and local short-term corticosteroids can be used. In cases of exsiccosis, the use of refatting and moisturizing externals is recommended. If symptoms cannot be controlled and if skin is destructive (e.g., necrosis), consider specialist referral. If there is evidence of psychological distress related to the skin lesions (e.g., pronounced fear of disfigurement with hair loss, compulsive hand washing), psychosomatic co-care may be useful. Patients should be informed that complete remission of skin lesions and hair loss is likely to occur after a period of time. Hair grows in cycles, and disease and stress can lead to reversible disorders (box) [2].

Literature:

- Rabady S, et al: Guideline S1: Long COVID: Wien Klin Wochenschr 2021; 133: 237-278.

- Koczulla AR, et al: S1 Guideline Post-COVID/Long-COVID. AWMF Register No. 020/027, as of 12.07.2021.

- Sivan M, Taylor S. NICE guideline on long covid. BMJ 2020; 371: m4938. DOI:10.1136/bmj.m4938

- Trüeb RM, et al: Experimental Dermatology 2021; 30: 288-290.

- Puta C, Haunhorst S, Bloch W: Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2021; 37(3): 214-225.

- Peyravian N, et al: J Inflamm Res 2020; 13: 879-881.

- Dennis A, et al: Medrxiv 2020, 2020.10.14.20212555.

- Iacobucci G: BMJ 2020; 371, m4470.

- Criado PR, et al: Inflamm Res 2020; 69: 745-756.

- Silva Andrade B, et al: Viruses 2021; 13. DOI: 10.3390/v13040700 60.

- Peiris S, et al: PLoS One 2021; 16: e0250708.

- Esen-Salman K, et al: Dermatol Ther 2021; 34: e14895.

- Kashetsky N, Mukovozov IM, Bergman J: J Cutan Med Surg 2021; 12034754211004575.

- Baeck M, Herman A.: Int J Infect Dis 2021; 102: 53-55.

- McMahon DE, et al: Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21(3): 313-314.

- Funke-Chambour M, et al: Praxis (Bern 1994) 2021; 110(7): 377-382.

- Lopez-Leon S, et al: Res Sq 2021; rs.3.rs-266574. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-266574/v1.

- Krajewski PK, Maj J, Szepietowski JC: Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 101: adv00366.

- Kendziora B, et al: Eur J Dermatol 2020; 30: 668-673. DOI: 10.1684/ejd.2020.3923.

- Gisondi P, et al. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2021; 39(5): 1099-1107.

- Martinez-Lopez A, et al: JAAD 2020; 83: 1738-1748.

- Zahedi Niaki O, et al: JAAD 2020; 83: 1150-1159.

- Landeck L, et al: Immunotherapy 2021; 13: 605-619.

- Thanou A, Sawalha AH: Curr Rheumatol Rep 2021; 23: 8.

- Yilmaz MM, et al: Am J Dermatopathol 2020. DOI: 10.1097/DAD.00000000001827.

- Zaladonis A, Huang S, Hsu S: Clin Dermatol 2020; 38: 764-767.

- Garg S, et al: Dermatol Ther 2020; e13859. DOI: 10.1111/dth.13859

- Cazzato G, et al: J Clin Med 2021; 10. DOI: 10.3390/jcm10081566.

- Birlutiu V, et al: Int J Infect Dis 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.058.

- Kaplan N, et al: Mol Cell Endocrinol 2021; 111260. DOI: 10.1016/j.mce.2021.111260.

- Peters EMJ, et al: PLoS One 2017; 12: e0175904. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175904 80.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE guideline (NG188): COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. 2020.

- Iqbal FM, et al: EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36: 100899.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(1): 22-23