- Long-term treatment with UPA for up to 5.5 years shows no new safety signals (1).

- UPA has a consistent safety profile in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and axial spondyloarthritis (AS), although the incidence of adverse events varies due to differences in the patient population and disease-related comorbidities (1).

- UPA has a comparable safety profile to adalimumab in RA* and PsA (1).

* With the exception of the already known higher herpes zoster and NMSC events and higher CPK levels.

UPA in rheumatic diseases

RA, PsA, and AS are highly stressful for those affected: the underlying inflammation can cause permanent joint damage and significantly reduce the quality of life of those affected [2, 3]. Upadacitnib (UPA, RINVOQ®) is an oral, reversible Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor that acts specifically on JAK1 and to a lesser extent on JAK2, JAK3 or TYK2. UPA is used at the dosage of 15 mg once daily for RA, AS, and PsA and is also approved for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) [4].

UPA showed strong efficacy in all 9 studies in RA, PsA, AS, and AD. However, safe use is equally critical to treatment [4]. Data from the ORAL surveillance trial, which compared the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor in elderly patients with RA and cardiovascular risk factors, underscore the need to better characterize the safety profile of JAK inhibitors in rheumatic disease therapy, particularly in the context of active comparators. A new publication by Burmester et al. now shows the long-term safety profile of UPA over a period of up to 5.5 years in rheumatic diseases, in which no new safety signals emerged [1].

Long-term treatment with UPA

Overall, the safety of UPA was studied in 6000 patients with RA, PsA, AS, and AD over 15 000 patient-years. In RA, AS, and PsA, a total of 9 phase IIb/III trials were included, i.e., data are available on 4298 treated patients who received at least one dose of UPA (3209 patients with RA, 907 with PsA, and 182 with AS). This corresponds to a total of 11272 patient-years (9079.1 for RA, 1872 for PsA, and 320 for AS, respectively) [1]. The maximum treatment duration was up to 5.5 years for RA, 3.9 years for PsA, and 3.3 years for AS. Approximately 80% of patients in all groups had at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease at baseline (Table 1). Older patients (> 65 years) were more prevalent in the RA population (20%) than in the AS population (6%) [1]. Patients who received at least one dose of ADA or MTX, respectively, were used for comparison. Most patients with RA and PSA taking UPA received concurrent csDMARD therapy – in patients with AS, additional csDMARD therapy was rare [1].

Table 1: Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of UPA, ADA, and MTX in RA patients and UPA and ADA in PsA patients and UPA in AS patients, respectively.

* Disease activity is measured as follows: RA, DAS (Disease Activity Score)-28 (CRP); PsA, DAPSA (Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis); AS, ASDAS (Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score).

†CVrisk factors include history of cardiovascular events, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tobacco/nicotine use, elevated LDL-C, and decreased HDL-C. Adapted from [1]

No new safety signals under UPA

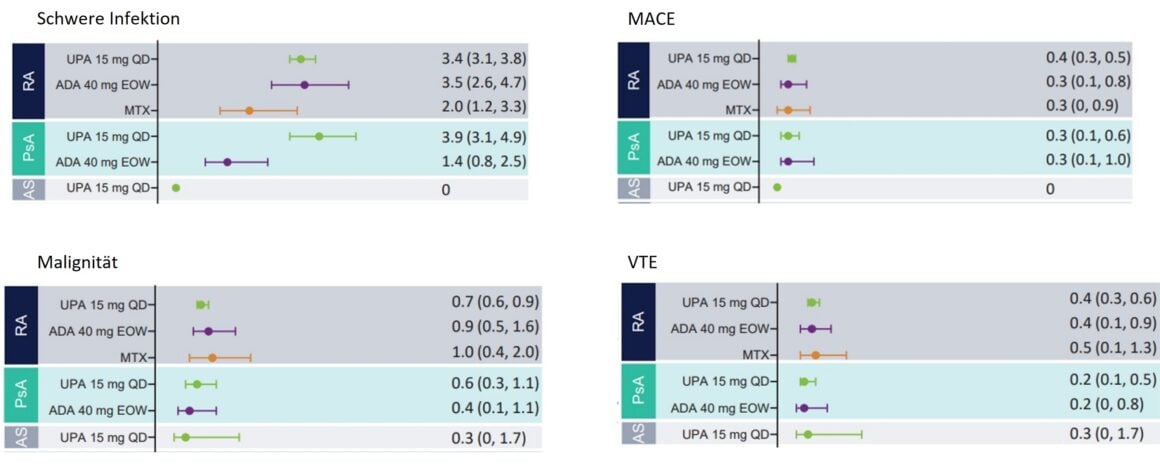

The overall safety profile of UPA was comparable in RA, PsA, and AS. Serious infections have been observed in patients with RA and PsA on UPA treatment (Fig. 1), rarely leading to treatment discontinuation, and were similar in frequency in RA patients on UPA as in patients on ADA therapy. In contrast, no serious infections have been reported in patients with AS receiving UPA therapy. The increased rates of severe infections in patients with PsA under UPA appear to be related to COVID-19 [1].

Malignancies (excluding Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer, NMSC) were reported at all disease stages at a rate up to a maximum of one event per 100 patient-years (≤1.0 E/100 PY) (Fig. 1), which was consistent across all diseases and also between UPA and the active comparator drugs. No significant change in this rate was seen throughout the duration of UPA use. NMSC rates with UPA -therapy (≤ 0.8 E/100 PY) were generally the same for all conditions, with the exception of AS – no malignancies were observed in this patient population [1].

Serious adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were reported in all treatment groups at rates <0.5 per 100 patient-years (PY) (Fig. 1). With the exception of UPA treatment of AS patients, where no cardiovascular events were observed. Overall, the rate of MACE was comparable in patients with RA and PsA receiving UPA, ADA, and MTX therapy. Whereas no correlation between the duration of UPA intake and the occurrence of MACE was revealed. Most patients who suffered MACE had at least one cardiovascular risk factor [1].

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) was observed in patients on UPA at all disease stages at rates of <0.4 E/100 PY in RA or 0.2 E/100 PY in PsA and 0.3 E/100 PY in AS. The number of events under UPA was comparable to that under ADA (RA and PsA) and MTX (RA) (Fig. 1). No association was observed between the duration of UPA exposure and the occurrence of VTE. Most patients who experienced VTE had at least one cardiovascular and/or thromboembolic risk factor [1].

Patients receiving UPA also had reports of herpes zoster, as expected. This was generally mild or moderate. Herpes zoster rarely led to interruption of therapy and affected only a single dermatome. In addition, no association between the duration of treatment and the incidence of herpes zoster was found [1]. Vaccination against herpes zoster is available. The vaccine should be administered 4 weeks before treatment with an active immunomodulatory agent such as UPA [4].

Figure 1: Exposure-adjusted rates of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) of particular interest in patients with RA, PsA, and AS. MACE, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events; VTE, Venous Thromboembolism. Adapted from [1]

Weighing the risk-benefit profile

Treatment of rheumatic diseases should aim to achieve sustained remission [5]. Remission not only improves treatment outcomes, but also reduces patient burden beyond disease symptoms. so remission reduces the risk of infection [6], CV [7], and possibly lymphoma [8]. JAK inhibitors have been shown to be an effective alternative for RA, AS, and PsA patients with inadequate response or intolerance to csDMARDs or bDMARDs [4]. The JAK inhibitor UPA has been and is being studied in extensive phase III clinical programs [1]. Initial long-term data of UPA evaluating safety and efficacy in patients with RA and inadequate response to methotrexate are available. UPA in combination with MTX is superior to ADA with MTX in terms of clinical response. Efficacy on joint symptoms was measured by ACR response criteria, pain intensity, and preservation of physical function. In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients under UPA achieved remission or low disease activity. Adverse event rates were comparable to ADA with the exception of herpes zoster, lymphopenia, liver dysfunction (mainly ALT and ALS elevations), and CPK elevations. Considering the benefits and risks of UPA compared with ADA, UPA showed better clinical outcomes with a comparable profile of adverse events (Fig. 2) [9].

Figure 2: Benefit-risk trade-off between UPA and ADA in a clinical context. The incremental number of patients meeting efficacy and safety endpoints was based on the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) and Number Needed to Harm (NNH) point estimates for treatment with UPA instead of ADA. a Statistically significant difference for UPA vs ADA (95% Ki). Adapted according to [9]

Conclusion

In summary, the safety profile of UPA is comparable in RA, PsA, and AS, and no new safety signals were observed even with long-term treatment with UPA of up to 5.5 years (1). In addition, UPA shows a consistent safety profile in RA, PsA, and AS, although the incidence of adverse events varies due to differences in the patient population and disease-related comorbidities. Overall, the safety profile of UPA in RA and PsA is comparable to that of ADA and MTX (1).

The full publication by Burmester et al. can be found here.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ADA, adalimumab; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALS, aspartate aminotransferase; CV, cardiovascular; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; DAS28, 28-joint Disease Activity Score; HZ, herpes zoster; IR, Inadequate Response; CI, confidence interval; LDA, Low Disease Activity; MACE, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Event; MTX, methotrexate; NNT, Number Needed to Treat; NMSC, Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer; NNH, number needed to harm; UPA, upadacitinib; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

References:

1. Burmester, G.R., et al, Safety profile of upadacitinib over 15 000 patient-years across rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and atopic dermatitis. RMD Open, 2023. 9(1).

2 Gudu, T. and L. Gossec, Quality of life in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2018. 14(5): p. 405-417.

3 Combe, B., et al, 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis, 2017. 76(6): p. 948-959.

4. current RINVOQ® (upadacitinib) technical information at

www.swissmedicinfo.ch

.

5. Smolen, J.S., et al, EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis, 2020. 79(6): p. 685-699.

6 Accortt, N.A., et al, Impact of Sustained Remission on the Risk of Serious Infection in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2018. 70(5): p. 679-684.

7. Solomon, D.H., et al, Disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of cardiovascular events. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2015. 67(6): p. 1449-55.

8. Baecklund, E., et al, Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum, 2006. 54(3): p. 692-701.

9. Conaghan, P., et al, Benefit-Risk Analysis of Upadacitinib Compared with Adalimumab in the Treatment of Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther, 2022. 9(1): p. 191-206.

The references can be requested by professionals at medinfo.ch@abbvie.com.

Report: Corinne Peter, MD

This article was produced with the financial support of AbbVie AG, Alte Steinhauserstrasse 14, Cham.

Brief technical information UPA

CH-RNQD-230016_04/2023

Online since 04.05.2023