Resecting procedures in the treatment of lymphedema have been in development since the beginning of the last century. They are invasive and have many complications. With the advancement of microsurgery, lymphovenous anastomoses play an important role in improving the patient’s quality of life.

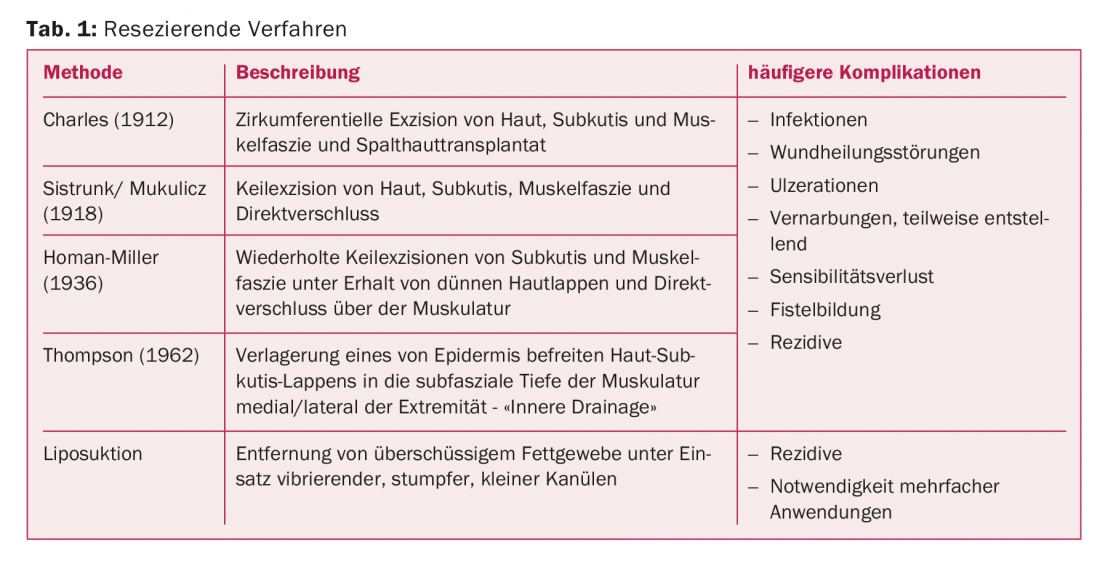

Resecting procedures in the treatment of lymphedema are methods that surgically remove excess tissue. Various procedures, some of them historical, have been described for surgical lymphedema therapy starting in the late 19th century (Table 1).

In 1912, the Charles procedure was developed in which the skin, subcutis, and muscle fascia were circumferentially excised and covered with split skin [1]. According to Sistrunk, wedge excisions of skin, subcutis, and muscle fasciae are performed with direct closure; the Homan procedure was the first to spare the skin and close it over the resected tissue defect [2]. This procedure is repeated until the desired circumference is achieved. The idea of connecting superficial and deeper lymphatics first became established in 1962 when Thompson resected subcutaneous tissue and relocated a thin deepithelialized skin subcutaneous flap to the subfascial depth of the muscle. As a result, not only disfiguring scars occur, but also lymphatic fistulas and pilonidal sinusoids are common [3].

Often, the healing process of resecting procedures is complicated by infections and the development of unstable scars. These methods are to be elicited in cases of disability and treatment failure in the final stage of lymphedema and can increase the effectiveness of causal therapies by reducing the so-called “lymphload”. They can be combined with reconstructive methods. In genital edema, these procedures are often considered earlier.

Liposuction

Liposuction is a special resecting procedure that can effectively reduce circumference in extremity lymphedema. Liposuction is the removal of excess fatty tissue by suction using vibrating, blunt and small cannulas. The transformation of lymphedema into fatty tissue (so-called fatty transformation) very often takes place in the later course of the disease. Swedish surgeon Hakan Brorson pioneered the use of liposuction for extremity lymphedema and has published promising results in recent years. In a prospective study of 56 lymhedema patients (29 primary, 27 secondary after cancer therapy), the circumference of the lower extremity treated by liposuction was still significantly similar to the healthy side after ten years [4]. However, affected individuals continued to wear compression stockings continuously. In another prospective study of 146 breast cancer patients who had developed upper extremity lymphedema, the excess volume was effectively removed and the reduced extremity circumference was maintained in the long term by consistent wearing of compression stockings [5]. In a large survey study, high levels of psychological and physical satisfaction were found among those receiving treatment [6].

The risk of additional lymphatic vessel damage from liposuction has not been observed experimentally or clinically. Anatomical examinations after longitudinal suction of the extremities failed to demonstrate damage to epifascial lymphatic vessels. Usually, no more than four liters of fat are suctioned per procedure to avoid circulatory problems and electrolyte shifts. Several interventions may be necessary.

Lymphovenous Anastomoses (LVA)

While interest in the role of the lymphatic system in physiological and pathological processes has grown in recent years, knowledge of the lymphatic system remains limited compared with knowledge of the cardiovascular system. Pathological mechanisms in lymphedema are now increasingly researched and the possibilities of surgical treatment are constantly expanding. To restore lymphatic drainage physiologically, lymphovenous anastomoses, which allow lymphatic drainage extraanatomically, are created supermicrosurgically. Supermicrosurgery is a new technique and advancement of microsurgery that allows very small vessels less than 1 mm (0.3-0.8 mm) in diameter to be dissected and sutured together. Very fine surgical instruments are specially made and microscopes with up to 40x magnification are used. Very thin suture materials are used, which have a thickness of 12-0 according to the USP classification (< 0.1 mm thread thickness). The creation of these delicate anastomoses is usually performed under general anesthesia for better patient comfort, but is in principle also possible under local anesthesia.

Lymphatic vessels themselves are difficult to visualize overall because they are small caliber and transport mainly clear and almost cell-free lymphatic fluid. Most visualization techniques rely on the natural ability of lymphatic vessels to absorb tracers injected into the tissue space. The tracer is then transported and concentrated in the lymphatic vessel, enabling various imaging modalities.

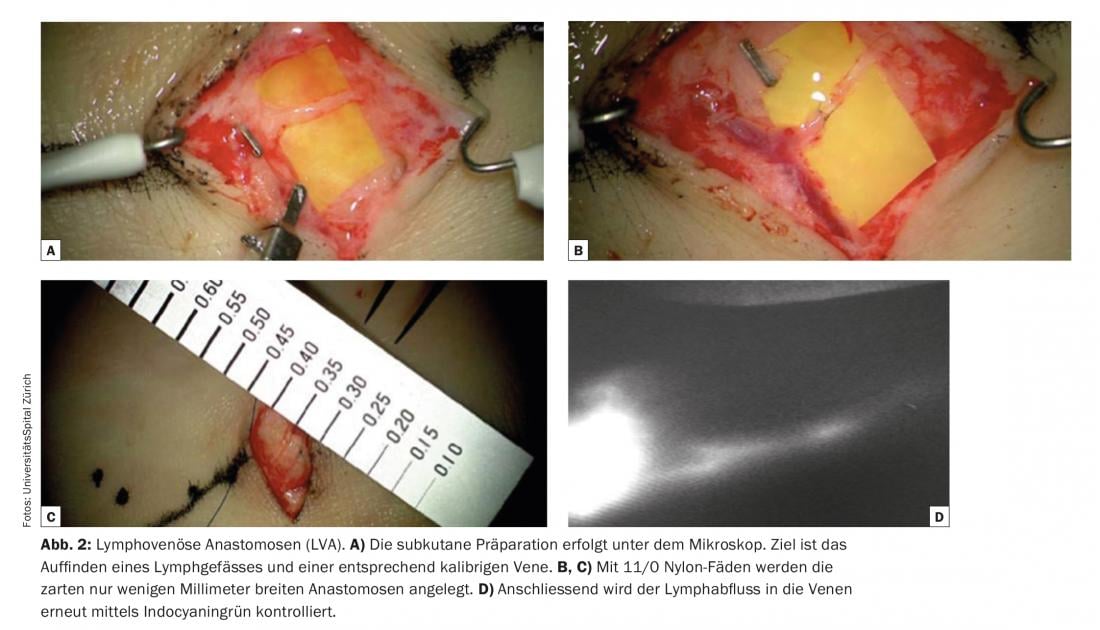

One of the elementary conditions for success of lymphovenous anastomoses is the identification of suitable lymphatic vessels that are not fibrotic but have a high transport capacity. Indocyanine green lymphangiography (ICG) is currently used as a comparatively simple and rapidly informative technique for imaging lymphatic vessels. In functional lymphatic vessels – e.g. of the extremities – the indocyanine green is quickly absorbed and rapidly transported in linear lymphatic channels to the groin or axilla. Often even peristalsis can be observed. ICG is used as a viable and cost-effective pre- and intraoperative navigation. Indocyanine green is injected dermally immediately preoperatively in the operating room to visualize superficial lymphatic vessels, e.g. between the toes on the dorsum of the foot, and the course of lymphatic vessels is marked on the skin. (Fig. 1). Subcutaneous preparation is performed under the microscope (Fig. 2). The goal is to find a lymphatic vessel and a corresponding caliber vein. Anastomoses are created with 11/0 or 12/0 nylon sutures. Subsequently, the lymphatic drainage into the vein is checked again by ICG. Often, additional lymphatic vessels in a given surgical area that were not visualized and registered by ICG preoperatively are only detected intraoperatively. These additional vessels are often larger and almost more suitable in diameter. The lymphatic drainage is partially visible with the naked eye. These so-called ICG-negative lymphatic vessels are increasingly used to generate additional anastomoses in the surgical area and to potentiate the drainage function.

To date, these clinical observations have not been reported in the literature. There is very limited overall experimental research in this area. Differential transport functions between two collecting vessels were demonstrated in a rat model [7]. Preferential lymphatic drainage patterns are thought to exist such that for a given tissue space, lymphatic drainage is the primary responsibility of a single vessel, with any additional vessels in the area serving only when the system is overloaded or as a back-up transport route for large lymphatic loads [7]. Differences in vessel depth and diameter may favor lymphatic drainage via a particular lymphatic vessel [7]. The effects of indocyanine green on normal lymphatic contractility and drainage function may also condition significant artifact [8].

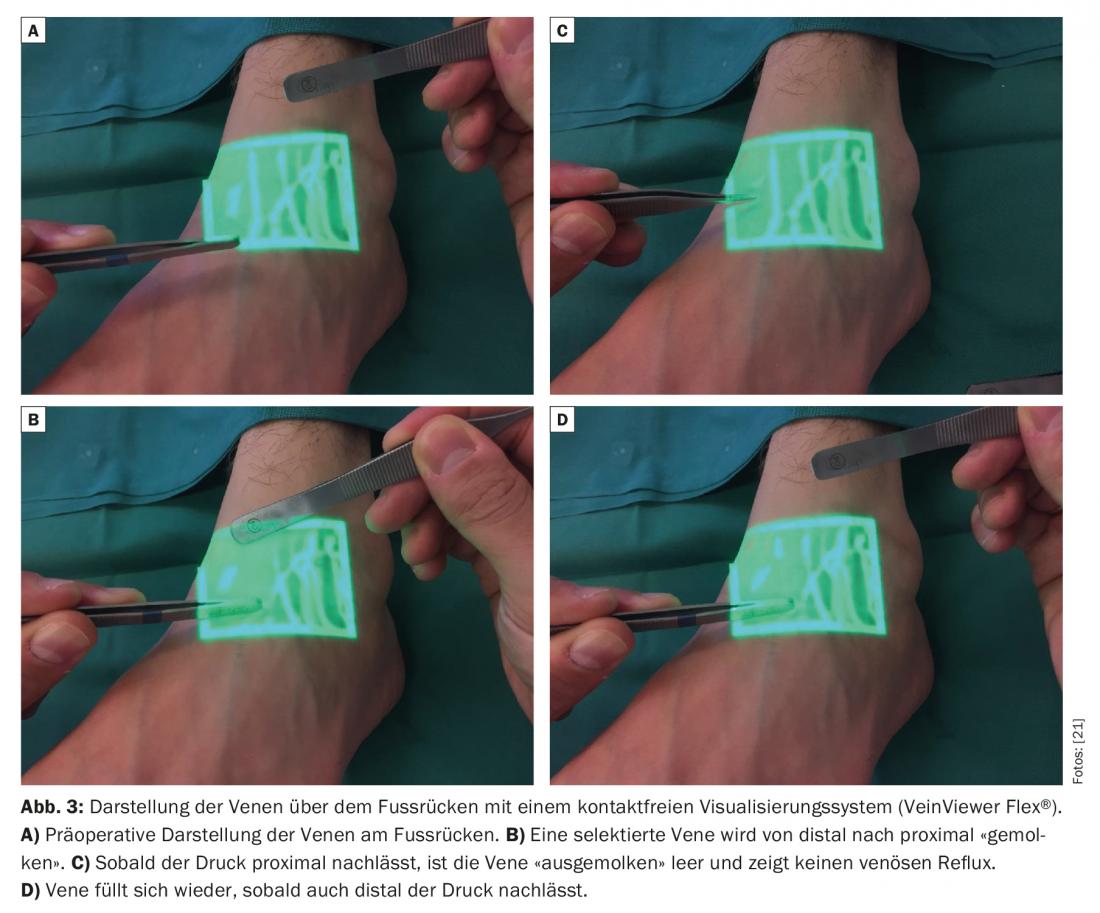

Identification of the small veins is also problematic in lymphedema patients because the subcutaneous fat is often thickened and the tissue is fibrotic. A suitable vein must be present in the immediate vicinity of a detected functional lymphatic vessel. Noncontact visualization systems for preoperative identification of subcutaneous venules with a diameter of approximately 0.5-1.0 mm have been reported in the literature to be promising [9].

Venous pressure is usually higher than in the lymphatic system [10,11]. Therefore, the absence of venous reflux is also of elementary importance. If the vein has an unsuitable valve system or an unfavorable course, venous backflow into the lymphatic vessel may occur. Thus, thrombosis and fibrosis of the anastomoses can significantly limit the longevity of the anastomoses [12]. Therefore, standard non-contact visualization systems are increasingly used to obtain a rapid venous mapping and to identify hidden bifurcations and inconveniently located valves in the veins that could potentially have a negative impact on the quality of the lymphovenous anastomoses created (Fig.3). Postoperatively, a light compression bandage is worn so as not to jeopardize the newly created delicate anastomoses. Patients remain hospitalized for one night. Skin lesions in breast cancer survivors with upper extremity lymphedema were thus reduced [13]. Many clinical studies have described circumferential reductions of 35% to 50% one year after placement of these anastomoses in breast cancer patients with arm lymphedema [14–16]. The discrepancy in these results is most likely due to the retrospective results with only a small number of cases. In a larger prospective study of 100 cases, researchers most recently determined a circumference reduction of up to 38% after three years and showed that there was also significant symptom relief subjectively [17]. Lymphedema-associated pain was relieved [18]. In another clinical study of 49 female patients suffering from secondary lymphedema of the lower extremities, it was found that the combination of lymphovenous anastomoses with liposuction can also significantly reduce skin texture as well as circumference [19]. It is postulated overall that the efficacy LVA is increased in the early stages (Fig. 4) . Case reports and reviews exist in the literature showing that the incidence of lymphedema after lymphadenectomy can be significantly reduced by prophylactic placement of lymphovenous anastomoses [20].

In summary, resecting procedures are invasive and complicating and are only considered in end-stage disease. Liposuction represents a special resecting procedure because it is less invasive and provides excellent results in many clinical studies. Resecting procedures may be combined with the creation of lymphovenous anastomoses in certain cases. The creation of lymphovenous anastomoses is a safe surgical procedure to date and has shown skin quality-improving and circumference-reducing results in the clinical and experimental studies available to date, although long-term results are still pending. Overall, further experimental studies and long-term clinical prospective studies with higher patient numbers are needed in the future to better prove the evidence of this therapy and to continuously optimize the procedure technically.

Lymphovenous anastomoses are internationally recognized as an integral part of surgical lymphedema therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- Resectioning procedures are invasive and fraught with complications. They are only considered in the final stage of the disease.

- The creation of lymphovenous anastomoses is a safe surgical procedure to date and has shown skin quality-improving and circumference-reducing results in the present clinical and experimental studies.

- Lymphovenous anastomoses are internationally recognized as an integral part of surgical lymphedema therapy.

Literature:

- Charles H: Elephantiasis of the leg. In: Latham A, English TC, editors. A system of treatment. Vol. London: Churchill 1912: 516.

- Sistrunk WE: Contribution to plastic surgery: removal of scars by stages; an open operation for extensive laceration of the anal sphincter; the Kondoleon operation for elephantiasis. Ann surg 1927; 85: 185-193.

- Thompson N: Buried dermal flap operation for chronic lymphedema of the extremitis. Plast Reconstr Surg 1970; 45: 541-548.

- Brorson H: Liposuction normalizes lymphedema induced adipose tissue hypertrophy in elephantiasis of the leg. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015; 136 (4): 133-134.

- Brorson H: Complete reduction of Arm Lymphedema Following Breast Cancer- A prospective Twenty-One Years Study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015; 136 (4): 134-135.

- Hoffner M, et al: SF-36 Shows Increased Quality of Life Following Complete Reduction of Postmastectomy Lymphedema with Liposuction. Lymphat Res Biol 2017; 15 (1): 87-98.

- Gashev AA et al: Indocyanine Green and Lymphatic Imaging: Current Problems. Lymphatic Research and Biology. 2010; 8 (2): 127-130.

- Weiler M, Dixon JB: Differential transport function of lymphatic vessels in the rat tail model and the long-term effects of Indocyanine Green as assessed with near-infrared imaging. Frontiers in Physiology. 2013; 4: 215.

- Makoto M, et al: Lower limb lymphedema treated with lymphaticovenous anastomosis based on pre-and intra-operative icg lymphography and non-contact vein visualization: a case report. Microsurgery 2012; 32: 227-230.

- Wardhan R, Shelley K: Peripheral venous pressure waveform. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009; 22: 814-821.

- Munn LL: Mechanobiology of lymphatic contractions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015; 38: 67-74.

- Yamamoto T, Koshima I: Neo-valvuloplasty for lymphatic supermicrosurgery. JPlast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2014; 67: 587-588.

- Jeremy ST, et al: Lymphaticovenous bypass decreases pathologic skin changes in upper extremity breast cancer rel. Lymphedema. Lymphatic Res Biol. 2015; 13: 46-53.

- Koshima I, et al: Supermicrosurgical lymphaticovenular anastomosis for the treatment of lymphedema in the upper extremities. J Reconstr Microsurg 2000; 16: 437-442.

- Furukawa H, et al: Microsurgical lymphaticovenous implantation targeting dermal lymphatic backflow using indocyanine green fluorescence lymphography in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 127: 1804-1811.

- Chang DW: Lymphaticovenular bypass for lymphedema management in breast cancer patients: A prospective study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 126: 752-758.

- Chang DW, et al: A prospectove analysis of 100 consecutive lymphovenous bypass cases for treatment of extremity lymphedema. Plastic Reconst Surg 2013; 132: 1305-1314.

- Mihara M, et al: Lymphaticovenous anastomosis releases the lower extremity lymphedema-associated pain. Plast Reconst Surg Global Open. 2017; 5 (1): e1205.

- Chang K1, et al: Liposuction combined with lymphatico-venous anastomosis for treatment of secondary lymphedema of the lower limbs: a report of 49 cases. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2017; 55 (4): 274-278.

- Jorgensen MG, et al: The effect of prophylactic lymphovenous anastomosis and shunts for preventing cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microsurg 2017; 00: 1-10.

- Scaglioni M, et al: Optimizing outcomes of lymphatic-venous anastomosis (LVA) supermicrosurgery by preoperative identification of reflux-free vein: Choose the vein wisely. Manuscript submitted to Microsurgery, 2017.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(5): 11-15