Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) affects women more often than men. There is no laboratory test that conclusively indicates CFS. The focus is on the exclusion of various root causes resp. -diseases, especially depression and burnout. Epstein-Barr virus and human herpes virus 6 are discussed as possible triggers.

Chronic fatigue is a multifaceted phenomenon that is always accompanied by a physical and mental lack of drive and performance. This has a negative impact on personality in today’s performance-oriented society [1]. In international parlance, chronic fatigue syndrome is also referred to as “myalgic encephalomyelitis” (ME). “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” (CFS). Then, in 2015, the term “Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease” (SEID) was proposed for the condition. For simplicity, this article will continue to refer to ME/CFS.

Epidemiology and clinic

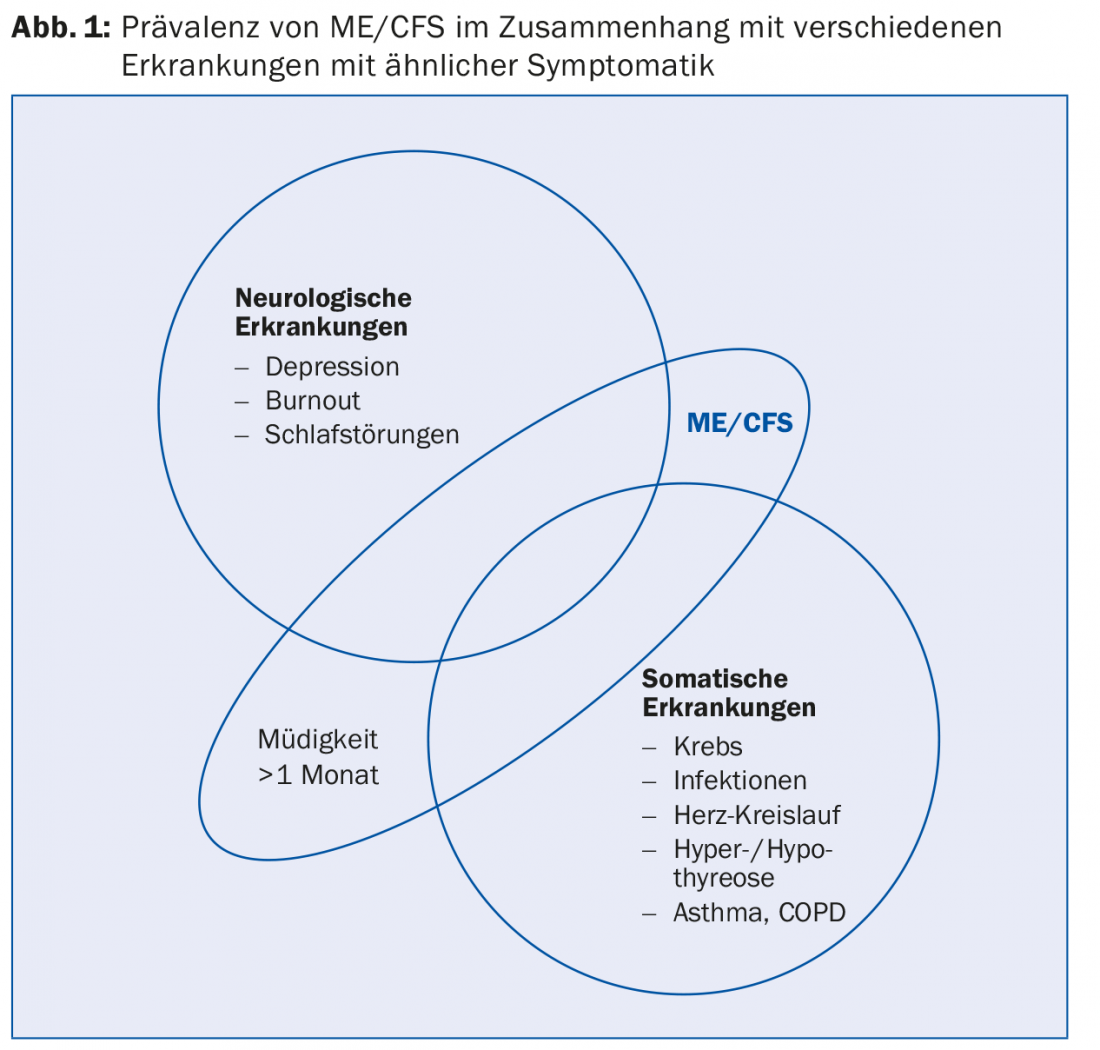

ME/CFS occurs in all age groups and ethnicities. In principle, women are affected twice as often as men [2]. According to a study from the United Kingdom, the prevalence of ME/CFS is approximately 0.2% (Fig. 1) [3,4]. So-called. Cluster outbreaks as well as an increased probability of occurrence in families suggest immunological or genetic causes [5]. A prominent example is the former German professional football player Olaf Bodden, in his time striker of the Bundesliga club TSV 1860 Munich, who developed ME/CFS and has not recovered from it until today [6].

Sleepiness and ME/CFS need to be clearly distinguished in the context of differentiation. Sleepiness is characterized by a tendency to fall asleep and can be relieved by short bursts of sleep or physical activity. In contrast, ME/CFS conditions cannot be corrected in this manner. Patients with ME/CFS report, among other things, “loss of energy,” mental fatigue, and lack of muscular endurance in varying degrees.

Many possible causes

The causes of exhaustion often lie in different areas of the individual’s life. Work-life balance factors, possible pregnancy and psychological constellations (depression, burnout) can already be elicited during the consultation. Obesity, bulimia, and anorexia nervosa can also cause fatigue syndrome. However, serious diseases (carcinomas) are also possible causes of persistent and uncorrectable fatigue. In addition, the attending physician must check the use of medications or the (beta-blockers, benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, glucocorticoids, statins) and alcohol consumption. Hormonal diseases such as Addison’s disease or Cushing’s disease must be ruled out, and clarification of hyper- or hypothyroidism is also an important differential diagnostic investigation. Treatable sleep disorders such as apnea syndrome and narcolepsy should be the focus of investigation.

Immunological causes must also be considered. Currently, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV, mononucleosis) and human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) are strongly suspected to cause chronic fatigue syndrome, as the syndrome occurs more frequently after surviving viral infections [5,7]. Several studies support the “transmissible agent” theory. However, screening for both pathogens is not specific because large portions of the population are latently infected with both types of virus. Other immunologic factors that can trigger general fatigue include hepatitis C, HIV, Lyme disease, and Q fever.

Laboratory tests

In general, there is no laboratory test that can specifically diagnose ME/CFS. Today, CFS is diagnosed in the majority of cases when no specific cause for the persistent fatigue can be proven. Studies show that only 5% of laboratory tests can clarify the causes of CFS, so targeted treatment can resolve fatigue. Physical examinations can even elicit the causes of ME/CFS in only 2% of cases [8].

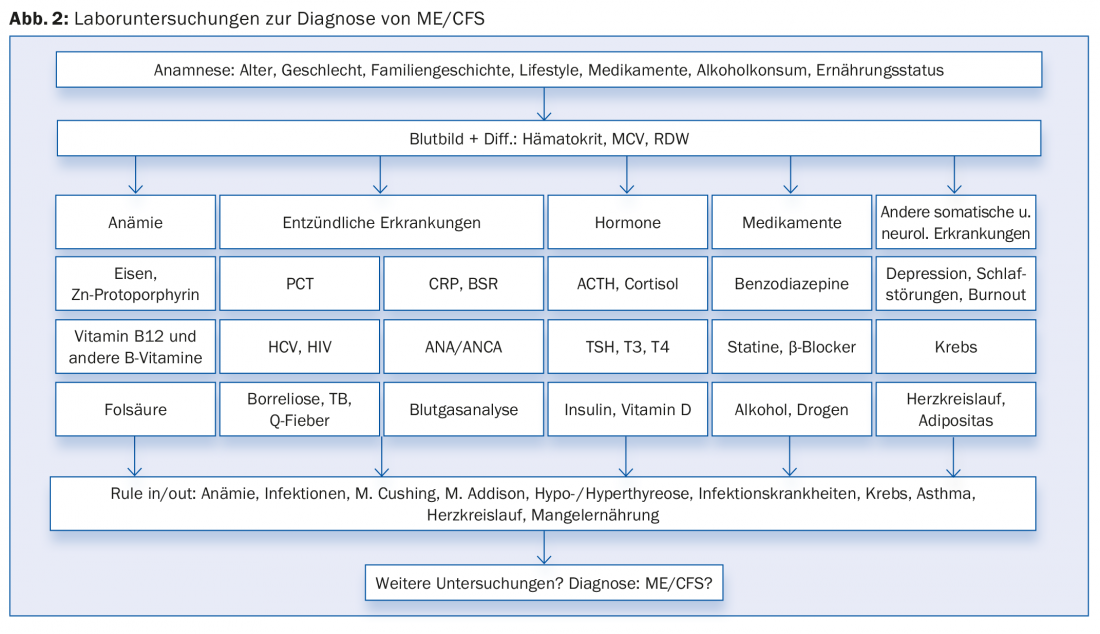

Laboratory tests are rule-out procedures, related to other pathological conditions. Laboratory tests that should be carried out in order to identify deficiencies or to determine the cause of the deficiency. The first step in ruling out the possibility of a disease is to check the classic parameters (Fig. 2) . First, a blood count plus differential blood count is requested. Hematocrit, hemoglobin concentration, MCV, and RDW can provide initial indications of deficiency situations.

If there is any suspicion, the iron metabolism should be examined more closely. With a prevalence of about 10%, iron deficiency is one of the most common deficiency symptoms in Northern Europe and a frequent cause of fatigue. Zinc protoporphyrin is a suitable marker to detect functional iron deficiency. It is recommended that additional biomarkers related to iron metabolism, such as soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR), transferrin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin, be determined in the further course. However, iron overload can also trigger ME/CFS-like symptoms.

MCH and consequently vitamin B12 and folic acid status are relevant parameters. Vitamin D levels should also be looked at more closely to diagnose ME/CFS. Especially during the dark season, vitamin D deficiency can lead to depression and fatigue [2]. Other trace elements that may be important in this context are selenium and zinc. Furthermore, various studies suggest a change in cortisol and possibly also interleukin 6 balance [9]. Thyrotropin (TSH), triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) are part of the standard repertoire in the clinical chemistry laboratory and should also be examined. However, changes in the neuroendocrine system are not significant to diagnose ME/CFS.

Inflammatory diseases can be included or excluded by the acute phase protein (CRP) or by the blood sedimentation rate (BSR). Analysis of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) provides further insight into any autoimmunologic and/or inflammatory pathologies that may be present.

Blood gas analysis provides information about oxygen/CO2 transport in the blood and may indicate obstructive and restrictive ventilatory disorders that can cause persistent fatigue. Unlike CRP and IL-6, severe systemic inflammation of bacterial origin results in elevation of procalcitonin (PCT). If viral and bacterial infections are suspected, screening for HCV, HIV, and Lyme disease and Q fever should be performed in the further course.

Conclusion

To date, there is no specific biomarker for ME/CFS. Rather, the diagnostic procedure is a process of exclusion of underlying somatic and neurological diseases.

Literature:

- Rosenthal TC, et al: Fatigue: an overview. American family physician 2008; 78: 1173-1179.

- Bested AC, et al: Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Reviews on environmental health 2015; 30: 223-249.

- Nacul LC, et al: Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC medicine 2011; 9: 91.

- Fukuda K, et al: The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Annals of Int Med 1994; 121: 953-959.

- Underhill RA: Myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome: An infectious disease. Medical hypotheses 2015; DOI 10.1016/j.mehy.2015.10.011 [Epub ahead of print].

- Theunissen T: The tired striker. Film documentary 2000.

- Carruthers BM, et al: Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. Journal Int Med 2011; 270: 327-338.

- Lane TJ, et al: The low yield of physical examinations and laboratory investigations of patients with chronic fatigue. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1990; 299: 313-318.

- Prins JB, et al: Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet 2006; 367: 346-355.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(4): 30-32