Melanocytic nevi are the most common benign neoplasms in fair skin types. Their number is a risk indicator for the development of malignant melanoma, of which they may be precursors. Accordingly, in dermatologic practice, the evaluation and control of melanocytic lesions is one of the most common issues.

On the occasion of the initial dermatological consultation, a whole-body examination is the basis of diagnosis, since it yields a relevant secondary diagnosis in 15-21.4% of patients. Regular skin examinations with respect to melanocytic lesions should be performed in cases of multiple atypical nevi, large congenital nevi (>20 cm DM), and st. n. malignant melanoma in personal or family history. With diagnostic options, whether clinical or reflected light microscopy, the dilemma is not to miss the malignant lesions and not to excise the harmless ones unnecessarily. To differentiate melanocytic nevi as benign lesions from malignant melanoma, knowledge of the different forms of nevi is helpful.

Melanocytic nevi

Common melanocytic nevi develop in children and increase to an average number of 20-30 lesions by adulthood. From 50 nevi or more the risk of melanoma increases by a factor of 4-5, from 100 nevi by a factor of 8-10. Nevi are an indicator of sun exposure in childhood, in which the damage is already set. Common nevi show different presentations – from lentigo simplex to junctional nevus, compound type nevus and dermal nevus.

Nevus bleu (nevus coeruleus)

Blue nevi are blue-gray or blue-black papules and nodules (Fig. 1) . Since the melanocytes here are located in the middle and upper dermis, the typical bluish color occurs as a result of the Tyndall effect. Blue nevi are not an indication for excision per se, but they seem to have an increased risk of degeneration on the hairy head, so that excision seems to be reasonable.

Halo nevus

The halo nevus is characterized by the typical depigmented halo around the pigment lesion (Fig. 2) . The nevus may disappear completely in the course. Patients with vitiligo show halo nevi more frequently. Malignant degeneration has not been described so far.

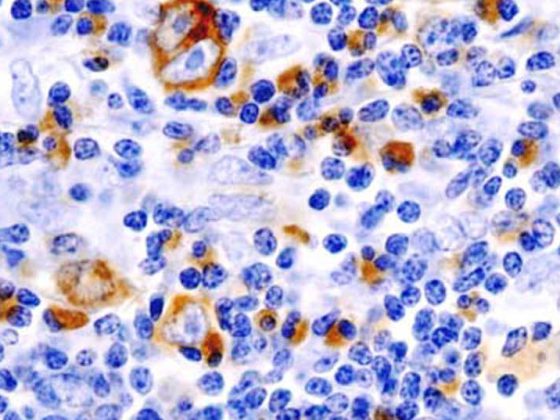

Atypical/dysplastic melanocytic nevi (Fig.3).

The terms “atypical” in terms of clinic or “dysplastic” in histology of nevi are not clearly defined. However, there is a clear need to differentiate conspicuous pigmentary lesions that deviate from the characteristics of the above-mentioned nevi. Characterization of such nevi is based on clinical (Table 1), light microscopic, and histologic criteria.

Helpful in the presence of multiple nevi can be the “ugly duckling phenomenon” (named after the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen) to identify the lesion which does not correspond to the general pattern. In the literature, however, the mention of the phenomenon was immediately followed by the indication that melanoma can also look harmless like the wolf disguised as a grandmother in the sense of a “Little Red Riding Hood phenomenon”. Atypical nevi can develop into malignant melanoma with a probability of 1:200 to 1:500. There is an increased risk of melanoma with multiple atypical nevi. In familial syndrome of atypical nevi, several family members are affected. These patients have a markedly high risk of developing malignant melanoma, and often multiple melanomas may occur in the same patient.

The decision to excise atypical nevi must always be made clinically and individually, as prophylactic excision is neither practical nor clearly supported by the data. If the dignity is unclear, excision should always be performed for histologic clarification.

Congenital melanocytic nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi are defined as melanocytic nevi present at birth or appearing no later than neonatal age. These are hamartomas, which occur in nearly 1% of all newborns. Clinically, sharply demarcated, homogeneously light to dark brown pigmented macules or plaques with a smooth surface and increased hairiness are found (Fig. 4).

According to the max. Diameter in adulthood, small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-19.9 cm), and large congenital melanocytic nevi (≥20 cm) are distinguished. To reach a diameter of 20 cm, the newborn must have a diameter of approx. 7 cm on the body or 12 cm on the head (prop. lower growth). This limit of 20 cm diameter is relevant because these nevi – especially those located axially – have an increased risk of melanoma formation. The risk of degeneration is between 5 and 15%, with tumor development occurring in the first five years of life in half of the cases. The tumors are often located in the dermis or deeper, they are often detected late and the prognosis is almost always infaust.

In addition, one large or multiple (≥3) smaller congenital melanocytic nevi may be indicative of neurocutaneous melanosis with extracutaneous melanoma development as well. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis with signs of intracranial pressure (hydrocephalus, seizures, cranial nerve deficits, and others) has a very poor prognosis quoad vitam, and surgical interventions should be avoided because they place additional unnecessary stress on the patient.

The nevus spilus consists of a café-au-lait stain with multiple darker, papular sprinkles in a disseminated distribution. Spitz nevus, recurrent nevi, acral nevi, and nevi localized along the milk line comprise the group of melanoma simulators and may present particular difficulties in histologic diagnosis, making appropriate clinical information particularly helpful to the histopathologist. Spitz nevus is characterized by rapidly growing melanocytic tumors often on the face in children and adolescents. Clinical presentation can vary from nodules with a smooth surface and light red to brown color (Fig. 5) to darker pigmented brown-black papules or nodules. The most important representative of pigmented Spitz nevi is the pigmented spindle cell tumor Reed (Fig. 6).

Due to the necessity to establish a histological diagnosis with clear exclusion of malignant melanoma, nevi should be excised in principle if indicated. Destructive procedures without histological reprocessing, e.g. with laser or electrocautery, are contraindicated. In excision, total excision should be sought in the first instance. Since UV exposure in the solarium and on vacation increases the risk for melanocytic nevi and thus also for malignant melanoma, attention should be paid to UV abstinence and appropriate sun protection with photoprotective agents and especially suitable clothing.

Malignant melanoma (Fig. 7)

An update of the 2006 Swiss melanoma guideline was published late last year. Some relevant aspects of the guideline are summarized below:

The main clinical decision aid for detecting melanoma is the ABCD rule as listed in Table 1.If melanoma is confirmed histologically after excision, re-excision should be sought within 4-6 weeks. The recommended safety distances are 0.5 cm for melanoma in situ, 1 cm for tumor thickness up to 2 mm, and 2 mm-2 cm for tumor thickness and greater.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is indicated when tumor thickness exceeds 1 mm (for ulcerated tumors or ≥1 mitosis/mm2 even for thinner tumors). This is a staging measure that is particularly useful when melanoma cells are detected in the sentinel lymph node and dissection of the affected lymph node station is performed. Because of the complexity of surgery, radiology, nuclear medicine, and pathology, sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed in specialized centers. During follow-up, clinical controls are sufficient for tumors less than 1 mm in thickness. For thicker tumors, additional imaging techniques are indicated. In high-risk situations, i.e., tumor thickness of 4 mm or more, PET/CT examinations are useful, especially in the first years of follow-up. Adjuvant therapy with PEG-IFNalpha2b may be useful in patients with micrometastases and/or ulceration. Patients with metastatic melanoma should be referred to specialized centers with interdisciplinary tumor boards. In addition to chemotherapy, primarily with dacarbazine and the more CNS-penetrating temozolomide, new treatment options include the anti-CTLA4 antibody ipilimumab and the selective B-Raf inhibitor vemurafenib. Despite the ray of hope offered by these new approaches, early detection remains one of the most important tasks, and it begins in the family physician’s office.

Siegfried Borelli, MD

Literature:

- Itin P: Ther Umschau 2000;57: 22-25.

- German guideline: Melanocytic nevi. JDDG 2011;9:723-736.

- Krengel S: Dermatologist 2012;63:82-88.

- Dummer R, et al: Swiss Med Wkly 2011;141:w13320.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(2): 14-16.