As the proportion of older people in society increases, the number of mentally ill older people necessarily increases. A Europe-wide study was able to show that today one in three elderly people suffers from a mental disorder. In this situation, inpatient psychotherapy can help reduce the existing gap in care. and the complexity of the clinical pictures. The article explains how such an offer should be designed and which therapeutic principles should be used as a basis.

As the proportion of older people in society increases, the number of mentally ill older people necessarily increases. A Europe-wide study was able to show that today one in three elderly people suffers from a mental disorder [1]. In addition, the disturbance patterns in old age are subject to change and often become more diverse and complex. Often, psychological limitations go hand in hand with physical and social limitations. This is one of the reasons that outpatient psychotherapy is often insufficient and elders are underrepresented in it [2]. In this situation, inpatient psychotherapy is an important supplement, not only to reduce the existing gap in care, but also because inpatient treatment, with its wide range of services, is more likely to be able to cope with the complexity of the clinical pictures in many cases [3]. How such an offer should be designed and which therapeutic principles should be used as a basis will be explained in the following.

Considerations on the structure of inpatient concepts for elderly patients

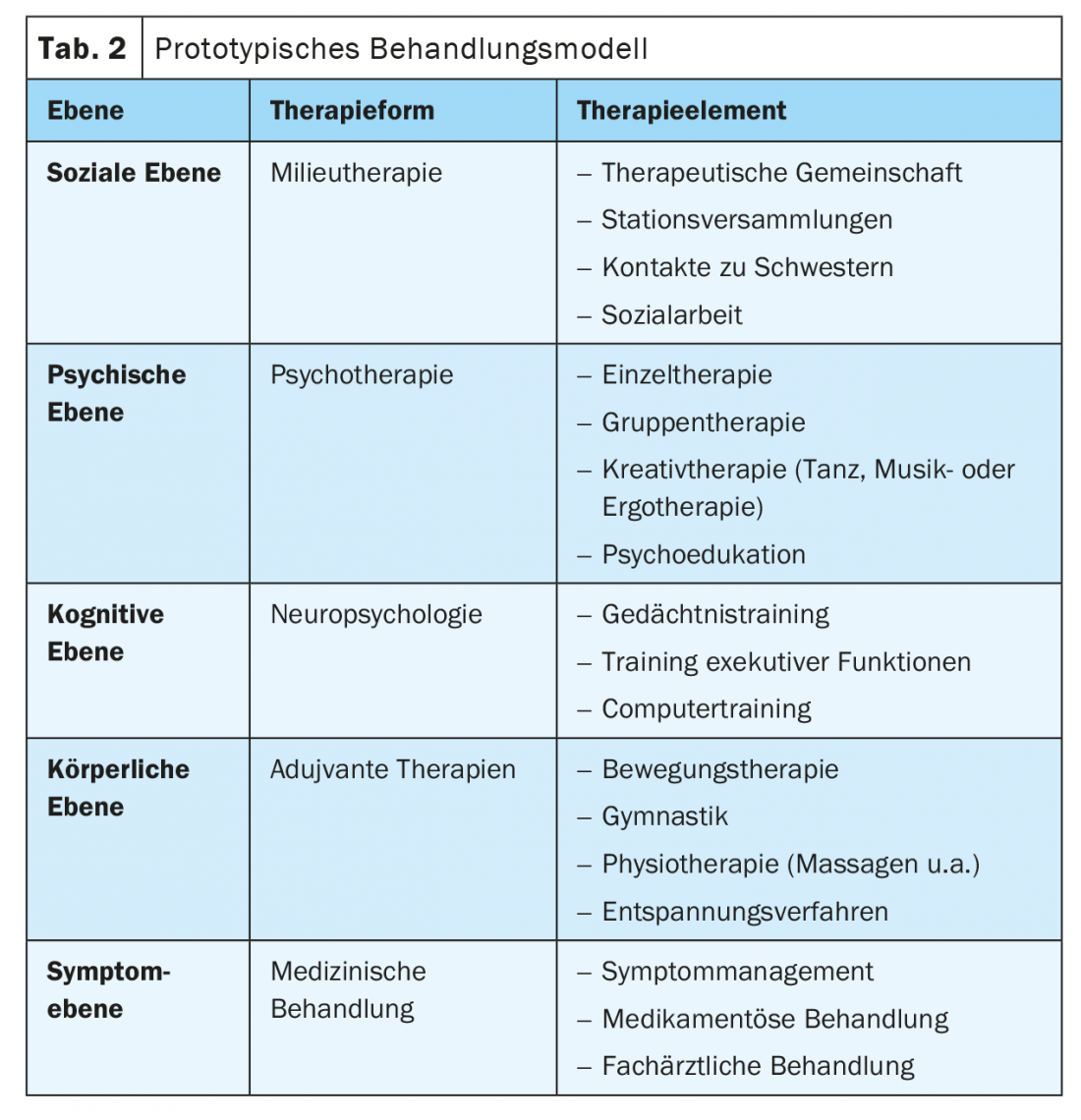

A priority question to be clarified is whether the elderly can be integrated into existing inpatient treatment concepts or whether it makes sense to set up separate services or departments for the elderly. Opinions differ in this regard not only in psychosomatic but also psychiatric clinics [4]. In table 1, arguments for both positions are summarized, whereby not only disease-related but also developmental psychological considerations are involved [5].

One essential aspect is missing from Table 1, namely the motivation and willingness of the elders themselves. In a qualitative survey conducted by Peters [6], it was found that the majority of patients were dismissive of an age-homogeneous ward on admission (“I’m not old after all”), but by the end the picture had been completely reversed. Now more than 90% of the patients expressed very positive. They valued contact with peers, experienced it as stimulating and supportive, and their fear of old age had been reduced.

In practice, pragmatic solutions are often required and mixed concepts tend to be practiced. Age-specific wards, for example, can be integrated into the overall clinic in a way that keeps boundaries permeable, or age-heterogeneous wards can integrate age-homogeneous services. However, it should be avoided to treat single elderly patients on wards with predominantly younger patients. In this case, they usually orient themselves to the senior physician or seek increased contact with nurses or prefer physiotherapy, i.e., in a situation of uncertainty they seek security in dyadic contacts [7], which can hinder a constructive therapeutic process.

Diagnostic tasks and multimodal concept

Every admission to a psychosomatic clinic begins with an admission examination, which includes physical, psychological, cognitive and social diagnostics. At all four levels, elders face special challenges:

- Physical level: The number of physical diseases increases with age, so extensive physical diagnostics are required. In advanced age and when multimorbidity is present, geriatric assessment is appropriate.

- Psychological level: A comprehensive psychological diagnosis (including possible suicidality and addictive behavior) including the recording of existing resources is required. Life history should also be obtained as comprehensively as possible, with particular attention to the question of previous traumatic experiences [8]. The question of whether it is a chronic disease or an actual conflict [9] that has developed in the course of a current stress situation is also important for the further indication.

- Cognitive level: the normal neuropsychological age changes make it necessary to check the cognitive status. If a mild cognitive impairment is suspected [10], this should be clarified by psychological testing, for which the CERAD* is suitable. Incipient dementia is usually a contraindication.

- Social level: The quality of life in old age is also significantly influenced by the external circumstances of life, which must therefore also be recorded. These include the question of contact frequency (loneliness), the housing situation and the financial situation, which is quite precarious for quite a few older people.

* CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease) is a neuropsychological test battery for the assessment of dementia. www.memoryclinic.ch/de/main-navigation/neuropsychologen/cerad-plus

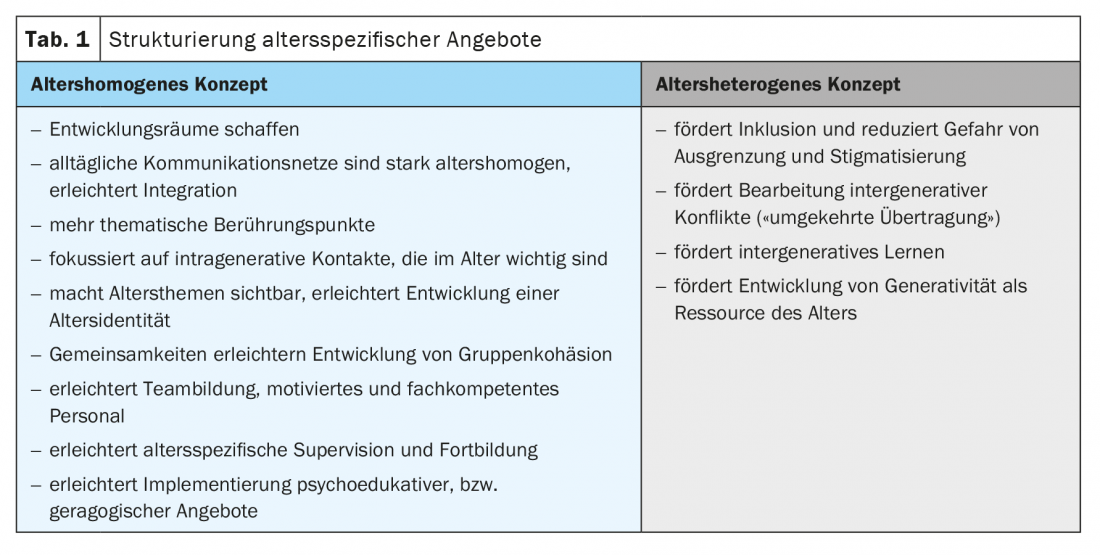

The treatment plan is derived from the diagnostics and must be designed flexibly and individually. Including patients’ ideas helps to strengthen their motivation for treatment. Table 2 gives an example of a possible treatment plan, although it may need to include fewer units for older patients than for younger patients. The listed therapy modules can be prescribed optionally and differ from clinic to clinic.

It is still significant that some building blocks should be modified and adapted according to age, which is true for adujuvant therapies as well as for neuropsychology. However, psychotherapy also requires an age-sensitive adjustment, which also concerns the peculiarities in the formation of relationships [11,12]. A psychoeducational group makes it possible to explicitly address the topic of age. At the symptom level, specialist co-treatment is more often required.

Mentalization-based foundations of the treatment concept

An effective, scientifically based treatment concept is not characterized solely by the juxtaposition of different treatment elements. Rather, there is a need for a framework that creates an internal connection and links these elements together. Only in this way can more than an additive effect, i.e. a synergetic effect, be generated that is capable of producing lasting changes. This distinguishes an inpatient concept from outpatient treatment in a special way. But how can this framework look like or be formulated?

Mentalization-based therapy (MBT) [13], together with structure-based therapy [14], represents one of the important new developments within psychodynamic psychotherapy. Both therapy developments, which differ only insignificantly, create a suitable basis for formulating such a framework. According to Bateman and Fonagy [15] mentalization can be understood as the mental process by which an individual implicitly and explicitly attributes meaning to his or her own behavior and the behavior of others, in terms of intentional states such as personal desires, needs, feelings, beliefs, and other motivations. The ability to mentalize can be represented in terms of a tension between polar dimensions, with problems most likely to arise when mentalizing shifts temporarily or permanently to one of the poles alone:

- automatic/implicit versus controlled/explicit

- internal versus external

- self versus other oriented

- cognitive versus affective

Therapeutic talk is about developing a Mental state talk [16], i.e., a talk that focuses on affects, intentions, perceptions, etc. This is based on the assumption that in this way people are enabled to better resolve their conflicts, burdens, life issues, etc. Thus, the ability to mentalize is of central importance with regard to mental health. Good mentalizing is characterized by a high degree of flexibility and alternates between self and other, cognition and affect, external and internal focus, or present and biographical narratives as appropriate to the situation. With regard to the elderly, however, there are now indications that the ability to mentalize may be impaired in old age, at least in some aspects and especially in the case of mental illness. For example, Peters and Schulz [17] were able to show that older people are less able to read the mental state of the counterpart from the eyes (theory-of-mind abilities), i.e., the other-related mentalization ability is reduced. Neuropsychological changes can contribute to this, as can life-historical stresses and traumas, which have a delayed effect only in old age and can reduce mentalizing ability [18].

In inpatient therapy, it is now important to identify mentalization deficits for each patient in the diagnostic process in order to be able to promote them in a targeted manner and thus improve the conditions for healthy aging. In most cases, the aim is to achieve a better balance between self- and other-related mentalizing, to supplement automatic mentalizing with explicit or reflected mentalizing, to expand affect perception or improve affect regulation, or to deepen internal mentalizing when the gaze is primarily directed outward. In the therapeutic dialogue, the focus should always be directed to the partial aspects of mentalizing that appear deficient. Good mentalizing is characterized by an integration of the various components; only then does it gain the flexibility needed to better deal with existential crises, losses or limitations. Since this integration is endangered in the elderly, the better integration of the sub-aspects of mentalizing can be formulated as an overriding goal, to which the various therapy modules can contribute in different ways.

But how can such a therapeutic goal be achieved? The basis of the mentalization-promoting process is the establishment of a sense of security, since uncertainty limits the ability to mentalize. Patients usually come to the clinic from a situation where they have experienced stress, uncertainty or loss. Since the admission situation is associated with further stress, the first step is to increase patients’ sense of safety in the clinic. This is all the more likely to succeed if the ward is designed as a “safe place” in which processes are transparent, information is presented in an age-appropriate manner, the therapeutic community quickly conveys a sense of belonging and, in particular, the nursing staff makes itself available as a “bonding object”, which is facilitated in a reference nursing system. The basic attitude of all involved practitioners should follow the concept of “collaborative communication “[19], which is characterized by responsiveness, reliability and openness and conveys confidence.

All those involved in treatment should adopt a basic attitude that is validating, supportive, and supportive of structure. Questions that stimulate self-reflection or invite the participants to explore their own experience more closely are particularly conducive to mentalization. Equally important, however, is the more explicit perception of others, or their mental state, in order to stimulate a change of perspective and improve other-related mentalization skills. Mirroring interventions [14], which make the own perception available to the patients (“If I had been in that place …”), also seem suitable . These are just a few examples from the broad spectrum of interventions [13]. However, the effort should always be to orient the therapeutic dialogue to everyday language. It can also be useful to awaken the storytelling skills that many elders possess, thereby giving them a sense of recognition and appreciation. It can also ensure that the dialogue does not focus solely on deficits and losses and the associated negative affect, which may be difficult to regulate. Rather, it is also important to generate positive affect and strengthen self-esteem in order to make negative affect associated with conflict and stressful situations tolerable. MBT is thus always competence and resource oriented. Last but not least, an atmosphere characterized by recognition and appreciation can also be implicitly significant with regard to an appropriation of old age, which is characterized by values such as receptivity, serenity and slowness, which facilitate successful aging [20].

All team members should identify with the basic therapeutic attitude described here, which also requires team members to reflect on their own age. Inpatient therapy takes place in a team, which as a whole should display a supportive and developmental attitude.

On the practice of mentalization-based inpatient therapy: a case study.

The 74-year-old patient of a psychosomatic clinic had worked as a physiotherapist. Her husband had been as successful as chief physician as her three sons. A mamma-ca 7 years ago had prompted the patient to end her professional life; in addition, the serious illness of her sister had recently been a problem for her. Her “men” were always very active, they made big bicycle tours and were also very engaged culturally. She had been participating less and less, feeling tired and exhausted, and she had also neglected her social contacts of late. “All I want to do is goof off,” she indicated. Her husband, in particular, showed little understanding for this; he was impatient with her and hardly ever there for her, increasingly turning to his activities outside the home.

But there was more at play: In ward life, the patient was initially quite active, participating in various activities and establishing numerous contacts with fellow patients. However, after some time she seemed more dissatisfied, complained about fellow patients and increasingly withdrew. Feedback was received from fellow patients indicating problematic interaction behaviors. She seemed quite “rambunctious” (“verbosity”) in conversations and only slightly able to respond to others as well. A few times she had apparently hurt fellow patients with thoughtless remarks. Similar abnormalities were also reported in the team discussion. The patient became increasingly unwell, complaining of physical discomfort and expressing thoughts of wanting to leave earlier.

It was also noticeable in the one-on-one interview that she made little reference and sometimes made rather “flippant” remarks, so that the question of cognitive changes soon arose. Thus, a neuropsychological examination was arranged, but it showed no evidence of dementia development or mild cognitive impairment (verified with the CERAD). However, deficits in executive functions were apparent, as reflected in the TMT (trail making test). The results indicated significant cognitive slowing. Deteriorated executive functions, however, are associated with impaired inhibition abilities, i.e., the ability to inhibit self-related cognitions deteriorates. However, this means that an important prerequisite for being able to grasp the mental aspects of the other person is missing [17]. Careless statements are then also more likely to be expected [21], which may then lead to irritation on the part of the counterpart, to which the patient in turn reacts by withdrawing. Presumably, a similar process of social withdrawal had taken place in the family or among friends as could now be observed in the ward.

Psychodynamically, a narcissistic conflict was to be assumed, i.e., own health problems and the care for the sister had partially alienated her from her family or from the high activity and performance norms lived by the “men”. From this point of view, it was a matter of dealing with this family ego ideal [22] or mentalizing it more explicitly and achieving narcissistic stabilization, to which the initial activation on the ward certainly seemed to contribute at first. But developments showed that this focus alone was not enough. Rather, it was important to focus more on the deficit in the ability to mentalize others, i.e., to repeatedly focus on the other person, to stimulate a change of perspective, and to consider more strongly the effect of one’s own statements on others. Again and again, it was also a matter of establishing a connection to one’s own experience of social exclusion and including this in the reflection process, i.e. establishing a link between other- and self-related mentalizing. The patient seemed to respond to this, so it was possible to relax relations with fellow patients again. As a result, the patient’s depressive mood, which had presumably exacerbated the cognitive deficits, was also reduced.

Treatment results

Although the negative stereotype of old age questions the ability of older people to change, gerontological research has long since painted the opposite picture. Plasticity is preserved even in old age, albeit with decreasing creative scope [23]. With regard to other-related mentalizing (ToM) skills, an Italian research team developed a training program by, for example, showing video sequences of social situations and asking group participants to share what the people involved were thinking and feeling and what their intentions were. Such Mental State Talk was shown to result in significant improvements in ToM skills, such as increased use of affective and mental terms; these improvements were also seen in the very old [16]. However, the elderly included were University of the Third Age participants, and this or a similar concept has not been previously tested in patients. Nevertheless, it can be pointed out that MBT contains very similar elements aimed at promoting a Mental State Talk . In the Hersfeld catamnesis study, which reviewed treatment outcomes in a psychosomatic clinic, the over-60s showed equally good effect sizes in the improvement of mentalizing ability as the younger patients; the improvement in mentalizing ability was accompanied by an improvement in symptomatology [24].

Conclusion

Inpatient treatments are an important complement to outpatient services for elders. However, gerontological psychiatric clinics with a psychiatric focus or geriatric clinics with an internal medicine focus are often available alone. Also in view of demographic developments, a third pillar of inpatient services with a clear psychotherapeutic orientation appears to be urgently needed.

Take-Home Messages

- Inpatient therapy is based on a multimodal concept combining psychological, physical, social and symptom-oriented treatment elements.

- Due to the multimodal approach, inpatient therapy is particularly indicated for older patients who have a complex clinical picture with physical comorbidity and socially problematic living conditions.

- Mentalization-based therapy focuses on promoting the mental processes by which meaning is given to one’s own and others’ behavior and experience. All treatment providers should identify with this basic attitude and thus create coherence in the diverse range of services.

Literature:

- Andreas S, Schulz H, Volkert J, et al: Prevalence of mental disorders in elderly people: the European MentDis_ICF65+ study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2016; 1-7; doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180463.

- Peters M, Jeschke K, Peters L: Elderly patients in psychotherapeutic practice – results of a survey of psychotherapists. Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics, Medical Psychology 2013; 63: 439-444.

- Peters M: Elderly patients in psychosomatic clinics. Fundamentals, Development, Perspectives. Psychotherapy in Aging 2018a, 15(1): 9-27.

- Stoppe G: Pros and cons: separate care of gerontopsychiatric patients. Psychiatric Practice 2006; 33: 258-260.

- Peters M: Clinical developmental psychology of aging. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2004.

- Peters M: Age homogeneous or heterogeneous? Reflections and findings on inpatient treatment of the elderly. Psychotherapy in Aging 2018b; 15(1): 87-103.

- Peters M: Catamnestic results on inpatient psychotherapeutic treatment of patients over 60 years of age. Journal of Gerontopsychology & Psychiatry 1994; 7: 47-56.

- Peters M: Mentalization Ability in Older Patients. An Empirical Contribution to the Effect of Trauma in Old Age. GeroPsych, J Gerontopsychol Geriatr Psychiatry 2021a; doi: 10.1024/1662-9647/a000267.

- Heuft G, Kruse A, Radebold H: Textbook of gerontopsychosomatics and geriatric psychotherapy. Heidelberg: UTB 2006 (2nd revised edition).

- Schröder J, Pantel J: The mild cognitive impairment. Stuttgart: Schattauer 2011.

- Peters M, Lindner R: Psychodynamic psychotherapy in old age. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer 2019.

- Peters M: Transference and countertransference in psychotherapy of the elderly. Medical Psychotherapy 2019a; 14: 78-83.

- Taubner S, Fonagy P, Bateman AW: Mentalization-based therapy. Göttingen: Hogrefe 2019.

- Rudolf G.: Structure-related psychotherapy. Stuttgart (Schattauer). 2nd edition, 2020.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. (Eds.): Handbook of mentalizing. Giessen: Psychosozial.

- Lecce S, Bottiroli S, Bianco F, et al: Training older adults on Theory of Mind (ToM): transfer on metamemory. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2015; 60(1): 217-226.

- Peters M, Schulz H: Theory-of-Mind skills in elderly patients with common mental disorders – a cross sectional study. Aging and Mental Health 2021; doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1935461.

- Peters M: Mentalization-oriented psychotherapy in old age. Psychodynamic Psychotherapy 2021b; 20: 220-233.

- Wallin DJ: Attachment and change in the therapeutic relationship. Lichtenau: Probst-Verlag (Original: Attachment in Psychotherapy. Guiford-Press 2007) 2016.

- Peters M: Living in limited time. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2011.

- Hippel von W, Dunlop SM: Aging, Inhibition, and Social Inappropriateness. Psychology and Aging 2005; 20(3): 519-523.

- Peters M: Narcissistic conflicts in patients in older age. Forum of Psychoanalysis 1998; 14: 241-257.

- Hertzog Ch, Kramer A, Wilson R, Lindenberger U: Enrichment Effects on Adult Cognitive Development. Psychological Science 2009; 9: 1-65.

- Peters M, Budde A, Lindner J, Schulz H: Elderly patients in the psychosomatic clinic – results of the Hersfeld Catamnesis Study 2022 (in prep.).

InFo PAIN & GERIATURE 2022; 4(1-2): 12-16.