Systolic or diastolic heart failure? In 10-20% of heart failure patients, the answer to this question is: neither. You have heart failure with an ejection fraction in the “mid-range,” that is, between 40% and 49%. At this year’s ESC-HF Congress, international experts explained in a symposium what this new entity of HF means and whether it has implications for patient care.

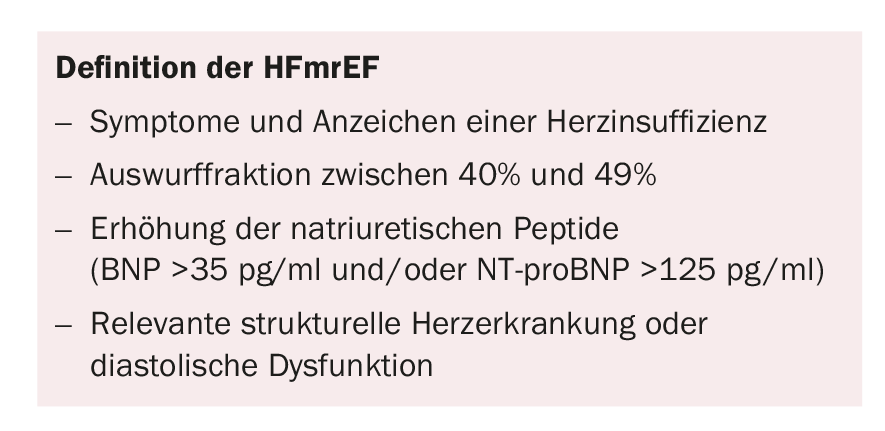

Until last year, European cardiologists distinguished systolic heart failure (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFrEF) from diastolic heart failure (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFpEF). The latter exists when ejection fraction is ≥50%, natriuretic peptides are elevated, and there is additional evidence of diastolic dysfunction on echocardiography with appropriate HF symptoms. However, since the 2016 European HF Congress, where new guidelines were defined, there is another new category: heart failure mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) [1]. It is present in patients with an ejection fraction between 40% and 49% and other characteristics (see box “Definition of HFmrEF”). 10-20% of all HF patients have HFmrEF.

The “sandwich child

“The HFmrEF is a typical sandwich child, that is, the middle of three children,” said Prof. Scott Solomon, Boston (USA). “The oldest child is doing everything for the first time and therefore gets a lot of attention, the youngest child is spoiled and coddled – and the middle child is kind of in between.” The situation is similar in heart failure, because it is often not clear what to do with patients whose ejection fraction is 40-49% [2]. However, this value is arbitrary, as is the definition of a “preserved EF,” which has been established in different studies at different values. The characteristics of patients with HFmrEF are in several respects more similar to those of patients with HFpEF, and in other respects they are more similar to patients with HFrEF [3]. In the CHARM study, the outcome of patients with HFmrEF was shown to be closer to the outcome of HFrEF patients than to that of HFpEF patients.

Look for coronary artery disease at HFmrEF

In an as yet unpublished study using data from the Swedish HF Registry, patients with HFmrEF were found to have a similar incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) as patients with HFrEF. “This is important information because CHD is treatable,” Prof. Carolyn Lam, Singapore, said in her presentation. There is also the question of whether a HFmrEF is simply a HFrEF “in transition” – that is, whether the corresponding patients tend to improve or deteriorate. In a recent study by Tsuji et al. showed that HFmrEF worsens rather than improves toward HFrEF [4]. A similar conclusion was reached by the authors of a study in which the data from the TIME-CHF study were examined again with regard to HFmrEF. Their conclusion: “…we hypothesize that HFmrEF has to be categorized as HFrEF because of the high prevalence of coronary artery disease and the similar benefit of NT-proBNP-guided therapy in HFrEF and HFmrEF, in contrast to HFpEF.” [5] Therefore, for the practical management of patients with HFmrEF, Prof. Lam offered the following tips:

- Look for CHD and treat patients appropriately.

- Consider therapies for ischemic HFrEF: RAAS inhibitors, beta-blockers in CHD.

- Patients with CHD are more likely to transition to another HF category. Transition to HFrEF is a sign of a worse prognosis.

What does the future hold?

Prof. Piotr Ponikowski, Wroklaw (Poland) gave an outlook into the future in his presentation. Disease-modifying, evidence-based treatment options are now available for HFrEF, but not (yet) for HFpEF. In between is the HFmrEF. In the QUALIFY study, the results of which were recently published, HFrEF patients treated according to the guidelines had a better outcome [6]. When patients’ treating physicians did not adhere to the guidelines, this was associated with higher all-cause mortality (HR 2.21), higher cardiovascular mortality (HR 2.27), and increased combined risk of hospitalization for HF or death due to HF (HR 1.26) at six-month follow-up. Whether this also applies to the HFmrEF is an open question.

The speaker pointed out that patients with HFpEF need targeted therapies that match the phenotype resp. are adapted to the comorbidities of HF (e.g., fluid retention, pulmonary hypertension, diabetes/obesity, or iron deficiency/anemia). For example, the EMPA-REG trial showed a good outcome for HF patients [7]. Currently, the EMPEROR trial is now underway, which explicitly investigates the effect of empagliflozin vs. placebo in patients with HFpEF and patients with HFrEF.

Source: symposium “How to manage heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF),” ESC Heart Failure Congress, April 29-May 2, 2017, Paris (F).

Literature:

- Ponikowski P, et al.: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18(8): 891-975.

- Lam CS, Solomon SD: The middle child in heart failure: heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (40-50%). Eur J Heart Fail 2014; 16(10): 1049-1055.

- Chioncel O, et al: Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.813. [Epub ahead of print]

- Tsuji K, Characterization of heart failure patients with mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction-a report from the CHART-2 Study. Eur J Heart Fail 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.807. [Epub ahead of print]

- Rickenbacher P, et al.: Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: a distinct clinical entity? Insights from the Trial of Intensified versus standard Medical therapy in Elderly patients with Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.798. [Epub ahead of print]

- Komajda M, et al: Physicians’ guideline adherence is associated with better prognosis in outpatients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the QUALIFY international registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.887. [Epub ahead of print]

- Zinman B, et al: Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117-2128.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(4): 36-37