Mental illness affects the mother and fetus, as well as later child development. Conversely, pregnancy can also influence the disease. These interactions present treating physicians with a special challenge that should be addressed in an interdisciplinary manner.

Depression during pregnancy is not uncommon. The causes are manifold and are shaped in advance by the hormonal change, the upcoming changes in life circumstances and the psychological constellation as well as by the genetic disposition. The prevalence is estimated to be up to 10% of all pregnancies. A few years ago, large maternal death statistics in England showed an increase in suicide-related maternal deaths in pregnancy; from 2000 to 2002, suicide was even the most common cause of maternal mortality-more common than cardiac events, thromboembolism, or peripartum hemorrhage [1].

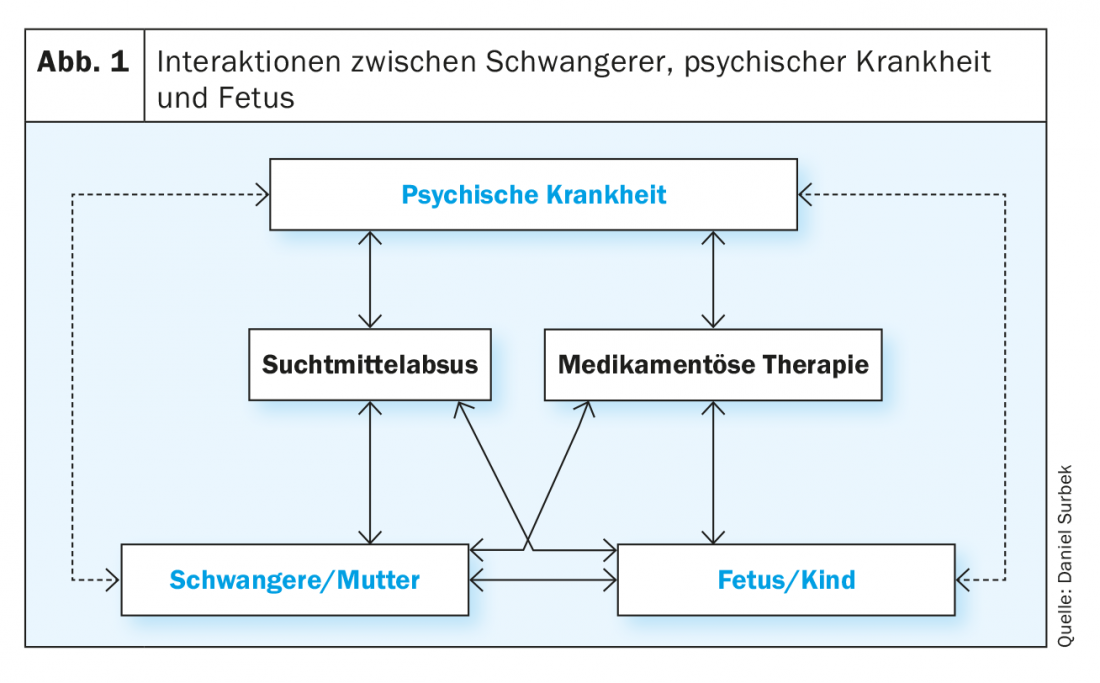

Interactions matrix

Multiple interactions exist between the mental illness, the maternal organism, and the fetus or its intrauterine environment, some of which are due to a direct effect and some of which are mediated indirectly by drug therapy or by an active substance in the context of substance abuse. These matrix-like structured interactions are often not clearly separable in clinical practice. Nevertheless, it is essential to consider the individual factors of an impact on both the pregnant woman and the child during prenatal care in order to achieve the best possible outcome for mother and child (Fig. 1). Mental illness (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, addiction) can affect pregnancy in a variety of ways.

Direct impairment due to the disease: this may be due to sleep disturbances, psychological and/or social stressors, eating disorders, anorexia or lack of weight gain, or lack of compliance with prenatal care. Possible consequences are:

- intrauterine growth retardation

- Prematurity

- intrauterine fetal death

- Birth complications

The link between psychological stress and pregnancy complications is now well studied. The main mediator is corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which in this context is also named the “coordinator of the stress response” [2]. CRH plays an important role not only as a mediator of the induction of preterm labor and subsequently possibly preterm birth, but also in the reduction of placental perfusion, which can lead to placental insufficiency with intrauterine growth retardation. Growth retardation often does not occur until the third trimester and is sometimes difficult to detect. Keeping in mind that mental illness can lead to suicide in cases of severe depression.

Indirect impairment by medication: Mental illness also affects pregnancy through an indirect mechanism mediated by drug therapy (see below). Therefore, it is important to realize that mental illness in pregnancy has a considerable prevalence. Recent studies show that depression occurs in up to 10% during pregnancy and the prevalence tends to increase [3,4]. Depressive episodes, which do not meet the criteria of an actual depression, but still have a disabling effect, occur in pregnant women even in up to 70%.

Influence of an addictive substance disease: Here, the different substance classes are to be distinguished with their respective very specific effects on the pregnant woman or the fetus. The substance classes and their potential effects are discussed below.

Recommendations for substance abuse

Nicotine abuse: still widespread, nicotine abuse typically leads to two major pregnancy pathologies: Prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. Interestingly, women with nicotine abuse have a somewhat decreased incidence of preeclampsia. The pathophysiological mechanisms leading to preterm birth and intrauterine growth retardation are essentially related to vasoactive substances in cigarette smoke and to the effects of carbon monoxide on the transplacental supply of the fetus. Due in part to the high prevalence of nicotine abuse, smoking cessation programs for women planning or in early pregnancy are among the most effective methods for reducing the high and still rising preterm birth rate in the population. Thus, appropriate medical intervention in female smokers is one of the most important preconceptional measures. In principle, “zero tolerance” should apply to pregnancy with regard to nicotine abuse [5].

Ethylabuse: alcohol abuse in significant amounts has severe effects on the fetus. In contrast to nicotine abuse, which has consequences for pregnancy primarily through placental hypofunction, alcohol has a direct toxic effect on the fetus. The consequences are circumscribed by embryofetal alcohol syndrome. This includes typical stigmata in the newborn (facial dysmorphia with high and flat philtrum etc.), microcephaly, cardiac malformations and a severe psychomotor and psychosocial developmental disorder, which often continues into adolescence. Because ethyl alcohol readily crosses the placental barrier at any time during pregnancy and, as a lipophilic substance, is directly toxic to the developing fetal brain, there is a direct dependence of alcohol dose in all three trimesters with respect to long-term developmental abnormalities. Therefore, in any case, alcoholics must try to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed in the course of pregnancy whenever possible, if necessary with psychotropic drugs. It is controversial whether there is a lower threshold amount of alcohol that can lead to fetal toxicity. It is relatively well established that the consumption of small amounts of alcohol (one glass of wine per week) does not have an adverse effect on the fetus. Nevertheless, alcohol consumption during pregnancy should be completely discouraged [5].

Opiate use: Opiate use by addicts can take the form of parenteral abuse (morphine, heroin) or enteral substitution (methadone, buprenorphine). Common to all forms of opiate abuse during pregnancy is transplacental substance habituation by the fetus, which manifests postpartum as neonatal opiate withdrawal syndrome. This includes shakiness, shrill crying, only short periods of sleep, and even neonatal convulsions. Treatment of the newborn usually involves initial parenteral opiate administration, which must then be phased out over several weeks in the form of slow withdrawal. Parenteral opiate use should be avoided in pregnancy whenever possible. Oral substitution with methadone has many advantages, although it too leads (in a nonlinear dose-dependent manner) to a neonatal withdrawal syndrome. Whether substitution with buprenorphine instead of methadone confers a benefit with respect to neonatal withdrawal syndrome is currently under investigation. In any case, as a principle of therapy, the goal should not be to reduce oral substitution to zero in the course of pregnancy, since experience has shown that the risk of uncontrolled abuse of parenteral opiates (or other substances, some of which are even more dangerous for pregnancy) increases sharply.

Cocaine, amphetamines: In this substance class, which has a dose-dependent vasoactive effect, the main pregnancy complications are intrauterine growth retardation, preeclampsia and prematurity. There is a high incidence of fetal malformations (e.g. gastroschisis). Premature placental abruption is a typical and severe acute complication, which often leads to intrauterine amniotic death or severe maternal complications (hemorrhagic shock, severe coagulopathy). For this reason, these substances are sometimes among the most dangerous during pregnancy, which is why their use during pregnancy should be avoided at all costs.

Tetrahydrocannabinol: Cannabis abuse in pregnancy is common. Possible consequences of this are intrauterine growth retardation and prematurity. Tetrahydrocannabinol also passes the placental barrier completely unhindered, similar to ethyl alcohol. Cerebral cannabinoid receptors are present at the earliest embryonic stages. This endocannabinoid system plays an essential role in cell proliferation, differentiation and migration. Intrauterine exposure to external cannabinoids may therefore have a negative impact on neuropsychological development. In addition, cannabinoid abuse during pregnancy affects endogenous opioid metabolism, which has been demonstrated in animal models. Whether and at what doses a long-term mental developmental disorder of the child occurs is debated differently. Some studies show an effect in terms of increased impulsivity in childhood. Neonatal withdrawal symptoms have also been described.

Infections in addiction: Clinical studies confirm that addicts suffer more frequently from infections, which can have consequences for the pregnancy or for the fetus. These infections typically include hepatitis B and C, HIV, syphilis, genital chlamydial infection, genital herpes, bacterial vaginosis, and genital HPV infection. The possible consequences of these infections vary depending on the pathogen. On the one hand, they can lead to increased risk of preterm birth (e.g., chlamydia, bacterial vaginosis); on the other hand, intrauterine or subpartum vertical transmission to the fetus can occur with corresponding consequences for the child (e.g., HIV infection, hepatitis C). Therefore, when caring for pregnant women with addiction, the various infections must be actively sought and, if necessary, therapeutic or prophylactic measures must be taken to prevent vertical transmission.

Effects of mental illness and medication on the fetus.

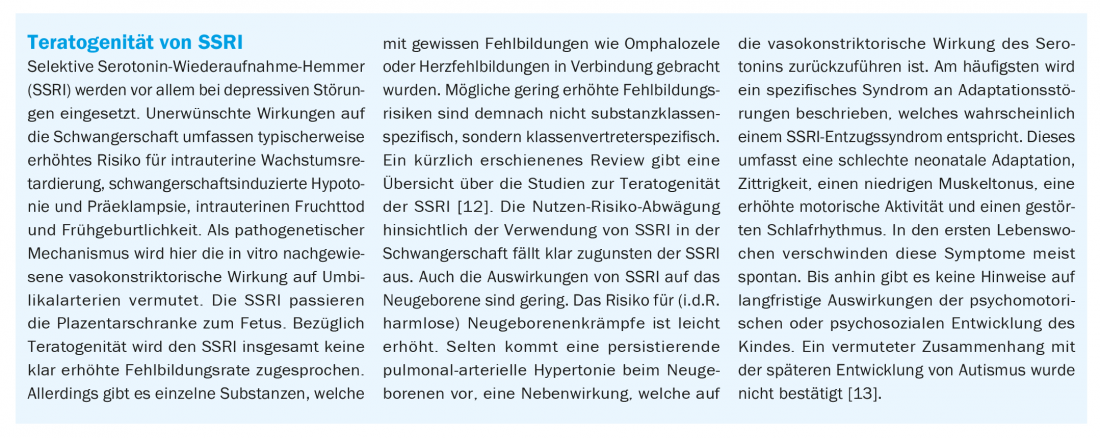

Because of the common occurrence of depression in pregnancy, the use of psychotropic drugs is prominent. A statistic from the USA shows that the use of antidepressants in pregnancy (especially SSRIs) has increased from 2% to about 8% in the last decade [4]. It is possible that this widespread use of psychotropic drugs does not reflect a general increase in depression in pregnancy, but rather a recognition that the benefits of psychotropic drugs in pregnancy are in many cases greater than their risks. Evidence now suggests that discontinuation of antidepressants during pregnancy or even preconception leads to a high recurrence rate of up to 75% [6,7]. In addition, studies have shown that depression per se leads to poorer pregnancy outcomes because it causes clustered intrauterine growth retardation and increased preterm birth. There is also the increased risk of suicide. In the run-up to pregnancy or at the beginning of pregnancy, therefore, a discontinuation of antidepressant medication should not be forced primarily, but a change to an antidepressant that is most compatible with pregnancy should be examined. In this context, there are some aspects to be considered with regard to the pharmacotherapeutic effects on the fetus, which will be discussed in the following.

Teratogenicity is characterized by exogenous induction of organ malformations, with exposure occurring primarily during the embryonic stage (delicate phase of organ development). The embryonic stage is defined until the end of the eighth SSW post-conception (i.e. until the tenth SSW after the last menstrual period). During the first two weeks after conception, the embryo is in the blastocyst stage. Here, the “all-or-nothing principle” is usually assumed: Any toxic influences do not lead to organ malformations, but to impaired blastocyst implantation in the endometrium and subsequently to spontaneous abortion.

The important phase of teratogenicity thus extends from the second to the eighth SSW post conceptionem. In the subsequent fetal stage, most organs have completed the major steps of differentiation. There is mainly a growth and at most a functional maturation. However, there are organs that continue to differentiate during the fetal stage. These include the fetal brain and fetal urogenital tract.

The boxes on page 8 explain two examples regarding the interaction between drug use and embryonic development. They illustrate the complexity of this relationship and the need for individualized risk assessment and adjustment of psychopharmacotherapy. Ultimately, it is important to weigh potential adverse side effects against beneficial effects (which often predominate in psychopharmacotherapy during pregnancy).

Long-term effects of mental illness on the child.

Based on the Barker hypothesis, it is now proven that prenatal influences on the fetus (intrauterine environment) result in the programming of individual organ systems or metabolic processes, which have lifelong effects on the child (“fetal programming”). The most important example is the association between low birth weight in intrauterine growth retardation and later risk of cardiovascular disease. Today, there is further evidence that prenatal exposure may also have consequences for mental health. For example, one study demonstrated an increased risk of suicide in adolescence and adulthood, respectively, in individuals with low birth weight [8]. Other studies show a significantly increased risk for depression in adulthood in preterm and low birth weight newborns [9,10]. It is believed that the key to the pathophysiological link between intrauterine exposure to certain conditions and subsequent psychiatric illness is mediated through the cortisol stress axis. This is evident even with short-term intrauterine stress exposure, as demonstrated in our recently published study on the relationship between different birth mode-related stressors, cortisol levels, and postpartum pain perception [11]. Children of mothers with a psychiatric illness have an increased risk of also becoming ill later on. In contrast to a genetic predisposition, intrauterine exposure is in principle therapeutically accessible.

Thus, our efforts in caring for pregnant women with mental illness must move in the direction of not only improving the short-term outcome of pregnancy, but also considering the potential long-term consequences for the child and how to prevent them.

How to care?

When caring for the pregnant woman with mental illness, potential reciprocal effects must be considered. It thus includes 1) the mental illness of the woman, 2) the utero-placental unit, and 3) the fetus as a second patient. In particular, the care of addicted pregnant women requires an overall care concept that increasingly includes the patient’s social environment and existing resources. Specific obstetric or prenatal care focuses on prevention, early detection and treatment of possible effects. These include the following key aspects:

Pillar I: Preconceptual counseling should be provided by the gynecology/obstetrics specialist jointly or in consultation with the supervising psychiatrist. Ideally, an appropriate plan for pregnancy should be established before stopping contraception. Efforts should also be made to plan the pregnancy at the most opportune time with regard to the mental illness. Furthermore, therapeutic aspects (drug selection) and preventive aspects (multivitamin/folic acid prophylaxis, reduction or stop of substance abuse) should also be considered. If pregnancy has already occurred, counseling must be started as soon as possible at the beginning of pregnancy.

Pillar II: The most important element in the diagnosis of pathological intrauterine developments is specialized prenatal ultrasonography. This means that fetal malformations can sometimes be detected early (12th SSW). Specialized sonography is of particular importance because many malformations (e.g. cardiac malformations) are difficult to diagnose and early diagnosis can significantly improve the subsequent outcome of the child. Detailed, non-directive counseling regarding prenatal diagnostic options must be provided in advance, including the “right not to know.” In addition, certain severe malformations can be treated intrauterine, whereas no therapy is possible postnatally. In a corresponding constellation with severe psychological impairment of the patient, abortion may also have to be considered. Other key diagnostic tests include close-meshed, longitudinal ultrasound examinations of cervical length, intrauterine growth, and fetal and uteroplacental hemodynamics (Doppler examinations). Today, it is possible to predict intrauterine growth retardation or preeclampsia in the early stages of pregnancy by means of blood flow measurements and additional biochemical tests. Pregnancies with mental illness must be considered high-risk pregnancies, which is why specialized prenatal medical care is urgently required.

Pillar III: Therapeutic interventions consist in the prevention of prematurity with appropriate drug (e.g. progesterone therapy) or surgical measures (e.g. cerclage) in case of fetal malformations. Especially with the increased risk of preterm birth, fetal therapy by means of correctly dosed transplacental glucocorticoid application (“lung maturation induction”) is often central, as this can reduce fetal morbidity and mortality by 50% in the event of preterm birth. In the case of a high-risk constellation for intrauterine growth retardation and for preeclampsia, drug prophylaxis (acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg daily, calcium supplementation 1-2 mg daily) is effective if administered in a timely manner. If severe intrauterine growth retardation with corresponding hemodynamic changes has already occurred or if severe preeclampsia is present, appropriate inpatient management with intensive monitoring of the fetus and timely delivery in case of exacerbation is the most important therapeutic measure. In any case, if the pregnant woman is mentally ill and if there are complications of pregnancy, it is imperative that pregnancy be managed in a tertiary center in an interdisciplinary manner to achieve the best outcome for mother and child.

Take-Home Messages

- Mental illness has multiple effects on the course of pregnancy as well as on the fetus and child development.

- Conversely, pregnancy can have an effect on a mental illness or promote its initial clinical manifestation through various influences, some of which are hormonal.

- The multifaceted matrix of interactions presents a particular challenge for interdisciplinary patient care, with psychiatrists and gynecologists/obstetricians at the forefront.

- Prenatal care is often complex and challenging and therefore requires collaboration with a specialized center to achieve the best outcome for both mother and child.

Literature:

- Hobel CJ, Goldstein A, Barrett ES: Psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008; 51(2): 333-348.

- Drife J: Why mothers die. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2005; 35: 332-336.

- Bennett HA, et al: Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103(4): 698-709.

- Andrade SE, et al: Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: a multisite study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 198(2): 194, e1-5.

- Bürki RE, et al: Current recommendations on preconception counseling. Expert Letter No. 33, Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2010. www.sggg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/33_Praekonzeptionsberatung_2010.pdf, last accessed 05.03.19.

- Cohen LS, et al: Relapse of depression during pregnancy following antidepressant discontinuation: a preliminary prospective study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2004; 7(4): 217-221.

- Cohen LS, et al: Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA 2006; 295(5): 499-507. erratum in: JAMA 2006; 296(2): 170.

- Barker DJ, et al: Low weight gain in infancy and suicide in adult life. BMJ 1995; 311(7014): 1203.

- Patton GC, et al: Prematurity at birth and adolescent depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184(5): 446-447.

- Thompson C, et al: Birth weight and the risk of depressive disorder in late life. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179: 450-455.

- Schuller C, et al: Stress and Pain Response of Neonates after Spontaneous Birth, Vacuum-assisted and Cesarean Delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 207(5): 416.e1-6.

- Koren G, Nordeng H: Antidepressant use during pregnancy: the benefit-risk ratio. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 207(3): 157-163.

- Hviid A, Melbye M, Pasternak B: Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors during Pregnancy and Risk of Autism. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 2406-2415.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(2): 6-12.