As every year, the ASH Congress took place in the busy pre-Christmas season. This time, experts from hematology and oncology met in San Diego. Multiple myeloma was again an important topic in 2016. Autologous stem cell transplantation was discussed. Are procedures such as so-called tandem transplantation or extended consolidation possibly superior to maintenance therapy with lenalidomide alone? And doesn’t quality of life suffer from continued active therapy anyway? New studies may partially clarify these questions.

Phase III studies [1–3] show that maintenance therapy with lenalidomide can improve progression-free and, in some cases, overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

A large randomized transplantation trial called StaMINA from the USA was now presented at ASH 2016, which tested other interventions in the context of autologous stem cell transplantation in comparison to the variant mentioned above. Here, all arms underwent maintenance therapy with lenalidomide at a maximum tolerated oral dose of 5-15 mg/d until progression (with dose modifications for toxicities). The median age was 57 years. Patients had been on initial therapy for one year or less (in more than half it was a combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone, and in 15% cyclophosphamide-bortezomib-dexamethasone) and were not allowed to show progression.

- In arm 1, 254 patients received melphalan 200 mg/m2 in preparation for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and four cycles of RVD consolidation (lenalidomide 15 mg/d on days 1-14, dexamethasone 40 mg/d on days 1, 8, and 15, and bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 21 days).

- In arm 2, 247 patients received a so-called tandem stem cell transplant (second transplant 60-180 days after the first) also with melphalan 200 mg/m2.

- In arm 3, 257 patients received single stem cell transplantation (plus melphalan 200 mg/m2).

The simple variant is enough

The primary endpoint of the phase III trial, progression-free survival at 38 months, showed no significant differences between arms. In the above order, the calculated PFS was 57%, 56%, and 52%. The same trend was found for overall survival (secondary endpoint): 86%, 82%, and 83%. In addition, there were no relevant differences in treatment-associated mortality – the overall rate was low (while overall survival was high in all three arms, as mentioned above).

The odds of a second tumor were 6%, 5.9%, and 4%, respectively, which were described as consistent with previous studies.

There were relevant differences in compliance: overall, 12%, 32%, and 5%, respectively, were noncompliant with the assigned therapy after the first transplant. Thus, especially the second transplantation could not be performed in one third of the cases.

A long-term follow-up of the study is currently underway. It remains to be seen whether a subgroup of patients may yet show an advantage of tandem transplantation. At present, such a benefit appears to be highly marginal.

Overall, the data suggest that less is more. A second transplant or extended consolidation with more chemotherapy provided no benefit. Although more detailed subgroup analyses are still pending, this is important news, including for patients, several experts at the congress said. Transplants in particular can be a stressful and costly procedure for those affected. The issue of expanded consolidation will certainly be a topic of discussion, as there are also results that point in a positive direction.

The Myeloma XI Study

One thing is certain: Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide is effective, and not only in patients who are candidates for transplantation. Myeloma XI, a phase III trial also presented at ASH 2016, again examined progression-free survival in newly diagnosed, symptomatic multiple myeloma after induction therapy with thalidomide or lenalidomide plus cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone – followed by transplantation with 200 mg/m2 melphalan for transplant-eligible individuals. These received lenalidomide maintenance therapy 100 days later, while non-transplant peers received it after maximal response. The dose was 10 mg/d in 21/28-day cycles – dose adjustments were allowed.

A total of 857 participants were administered maintenance therapy. The aim now was to compare the survival values with those 693 patients in the study who had not received any maintenance therapy at all.

Benefit confirmed

The interim data after 26 months of follow-up clearly favor the former strategy:

- Median progression-free survival was 37 vs. 19 months. Compared with no maintenance therapy, maintenance thus reduced the risk of progression by a significant 55% (HR 0.45; 95% CI 0.39-0.52). Significant values were found in both the transplant and non-transplant groups (54- and 56-percent risk reduction at 60 and 26 months median PFS, respectively).

- The results were independent of response or induction therapy and were evident across different risk groups.

- 21.5% stopped lenalidomide therapy due to toxicities. In patients who received lenalidomide for more than a year, the benefit was particularly pronounced compared with those who had to stop lenalidomide therapy a year ago (for other reasons, not progression) – the risk of progression was reduced by a whopping 65%. This was shown by initial exploratory analyses.

- Grade 3 and 4 adverse events included neutropenia (35%), thrombocytopenia (7.4%), anemia (4.4%), peripheral neuropathy (1.4%). 72 Secondary Primary Malignancies (SPM) were observed (48 of them in the maintenance group). Venous thromboembolism occurred in 2.3% of cases.

What about the quality of life?

In principle, maintenance therapy always carries the risk of negatively affecting health-related quality of life. Nevertheless, relatively few studies exist in the field of multiple myeloma that have examined this aspect of maintenance therapy in more detail, especially after autologous stem cell transplantation.

Therefore, there was also new evidence on this at ASH 2016, from a large U.S. prospectively observed cohort of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who, after induction therapy plus first-line transplantation, had undergone either unspecified maintenance therapy (including lenalidomide alone), lenalidomide alone, or no maintenance at all. There were 238, 167, and 138 subjects in the respective arms, with a median age of 60 years (61% were men, 64% had an ECOG performance status of 0/1, and 56% suffered from ISS stage I/II tumor). Those with maintenance therapy had already received triplet therapy more frequently as induction (64%, 66%, and 51%, respectively).

Quality of life comparable

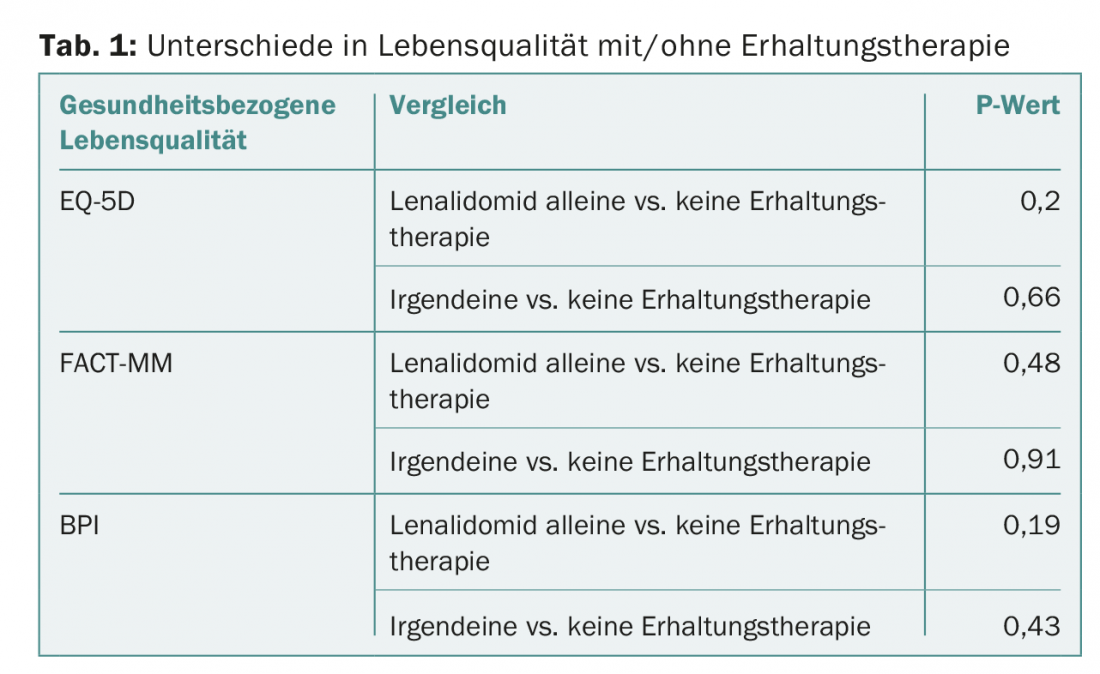

Quality of life was assessed with the EQ-5D index. Secondary endpoints were the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Multiple Myeloma (FACT-MM) and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). On average, maintenance therapy lasted 23 months in the first, unspecified group and 24.4 months in that on lenalidomide alone.

On median, patients in each arm completed the EQ-5D questionnaire on this topic completely approximately five times each. Baseline quality of life scores were comparable in the three groups, ranging from 0.75 to 0.76 on the EQ-5D.

Even after transplantation and with maintenance therapy, the values in the three aforementioned scores did not differ significantly from those in the group without maintenance therapy (Tab. 1) – a result that can encourage patients with continued active therapy.

Source: ASH 58th Annual Meeting and Exposition, December 3-6, 2016, San Diego.

Literature:

- Attal M, et al: Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012 May 10; 366(19): 1782-1791.

- McCarthy PL, et al: Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012 May 10; 366(19): 1770-1781.

- Palumbo A, et al: Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2014 Sep 4; 371(10): 895-905.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(1): 30-33.