The prevalence of non-alcoholic liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes is increasing worldwide. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance are major risk factors for NAFLD and steatohepatitis (NASH). Targeted screening and adequate interventions can reduce liver-specific and diabetes-related consequences and complications.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in Europe and the United States [1]. NAFLD is considered a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome, but may occur independently. Obesity is considered a common risk factor for NAFLD and type 2 diabetes (overview 1) . “In the collective of type 2 diabetics, there is twice the prevalence of NAFLD compared to the general population,” explains PD Dr. med. Thomas Karrasch from the University Hospital Giessen and Marburg (D) referring to a study published in the journal Diabetes Care [22,23]. On the one hand, diabetes promotes the progression of NAFLD to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and increases the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma; on the other hand, NAFLD is associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes [5].

Risk of progression of fatty liver disease is increased

NASH is present in about 30% of NAFLD sufferers and about 10-20% of cirrhosis and various forms of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are attributed to NAFLD [2,3]. The observed increase in incidence of HCC in Western industrialized countries has been attributed to the increase in NAFLD and NASH, among other factors [4]. In one study, type 2 diabetics had twice the risk of NAFLD progression [7]. Recent studies from the German Diabetes Study indicate that the severely insulin-resistant diabetes subtype in particular shows a greater increase in surrogate markers of fibrosis in the first 5 years after diabetes diagnosis [6]. Detecting NAFLD patients with a risk constellation for the development of HCC will become more important in the coming years, according to the corresponding conclusion of the 2021 consultation version of the S3 guideline “Diagnosis and Therapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Biliary Carcinomas.” It is important to identify an increased risk of HCC using predictive markers and to monitor it in the context of early detection [8]. According to the German NAFLD guideline, a combination of laboratory diagnostic and demographic assessment systems as well as non-invasive instrumental diagnostics can be used for this purpose [3,10].

|

There is currently a lot going on in the area of research into drug options for the treatment of NAFLD. Different therapeutic approaches are being tested experimentally and clinically, so specific treatment recommendations for the increasing number of patients with NAFLD and diabetes should be expected in the near future [2,19]. According to a review published in 2021 in the Journal Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology , of the active compounds currently under investigation, obeticholic acid has the most promising interim record in phase III trials [15]. |

Early detection: FIB-4 index and NFS as non-invasive scores.

Patients in early stages of NAFLD are usually asymptomatic. Surrogate scores such as the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index and the NAFLD-specific fibrosis score (NFS) have been introduced to detect patients at risk [11]. The NFS takes into account age, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus/impaired fasting glucose, platelet count, albumin, and de-ritis quotient (AST/ALT) [12]. While the FIB-4 score is easier to calculate using the parameters of age, AST, ALT, and platelet count, its positive predictive value is only 65% compared to about 90% in the case of the NCCR [11]. These noninvasive procedures can be used as complementary tests to determine hepatic steatosis and fibrosis.

FibroScan® and CAP: diagnostic methods with high sensitivity

Laboratory diagnosis of NAFLD may be suggested by elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT, GPT) with normal aspartate aminotransferase (AST, GOT), although up to two-thirds of NAFLD patients have normal liver enzymes [13,14]. Sonography of the liver can reveal steatohepatitis but cannot distinguish between NAFLD and NASH [11]. Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP), transient elastography (FibroScan®) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver have higher sensitivity than ultrasound [10]. CAP is a noninvasive method for quantifying NASH based on transient elastography, a technique that uses ultrasound and low-frequency elastic waves whose propagation speed is closely related to tissue stiffness [11].

MRI for quantification of liver fat content.

Non-invasive MRI techniques allow precise determination of liver fat content and are nowadays preferred to liver biopsy for quantification of fat content [2]. However, liver biopsy remains the most appropriate method for the diagnosis of inflammatory changes in the setting of NASH and is also considered seminal for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis.

For a confirmed diagnosis of NAFLD, hepatic fatty degeneration demonstrated by imaging (sonography, magnetic resonance imaging) or liver histology is required. The criterion for NAFL is a percentage of 5% or more fatty hepatocytes [16]. Differential diagnosis is to exclude excessive alcohol consumption (alcohol intake in women <20 g/day, in men <30 g/day) and other causes of liver injury such as viral hepatitis, alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and drug-associated steatohepatitis (DASH) [17].

| Pathophysiological link between metabolic disorders and NASH.

Pathophysiologically, NASH is due to lipid-induced hepatocyte damage, immune cell-mediated inflammation, and consecutive liver fibrosis [9]. Insulin resistance and obesity promote excessive fat accumulation in hepatocytes, increasing the sensitivity of hepatocytes to oxidative stress, endotoxins, and the action of cytokines, resulting in tissue inflammation [11]. These events promote the transition from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis and NASH, respectively, which is characterized by steatosis, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and ballooning of hepatocytes and focal necrosis [17]. Chronic inflammation and liver damage can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Weight reduction to lower the risk of progression

A reduction in body weight is associated with a lower prevalence of NAFL and may lead to fibrosis reduction in NASH. Accordingly, dietary changes and physical activity are important pillars in the treatment of NAFLD as well as for the prevention of progression. The effectiveness of lifestyle intervention depends on the extent of weight reduction achieved. A weight loss of about 5% results in approximately a 30% decrease in liver fat content [2]. In a prospective study over a 7-year period, a 5% weight reduction was shown to result in disease remission in 75% of NAFLD patients [18]. Nutritionally, a reduction of rapidly absorbed carbohydrates, especially fructose-containing products, and of saturated fatty acids is recommended [2]. Complementary to a balanced diet, an additive effect can be achieved through regular physical activity (combination of endurance and weight training) [19]. In cases of severe obesity and type 2 diabetes, bariatric surgery can lead to a pronounced reduction in liver fat content in parallel with weight loss.

What are the pharmacotherapeutic implications?

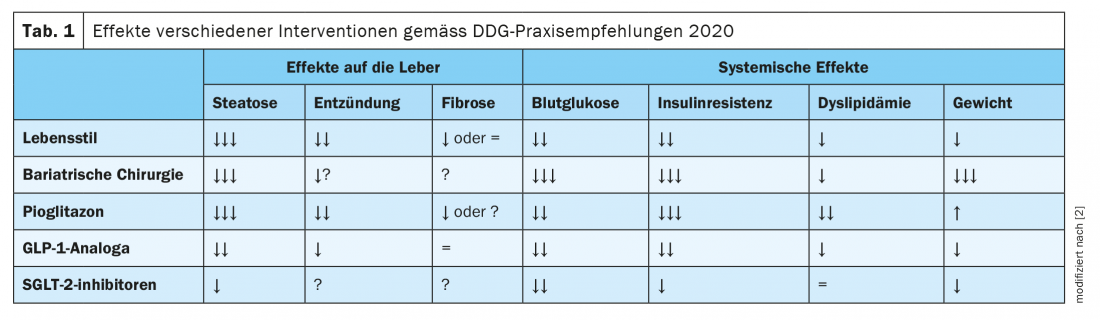

Although no pharmacological therapy for NAFLD has yet been approved. However, in the presence of type 2 diabetes, targeted medications can be used to treat the diabetes, which also have a beneficial effect on NAFLD. The joint guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), and the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), as well as those of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, recommend the use of pioglitazone if there are no corresponding contraindications (heart failure, history of bladder cancer, increased risk of bone fractures). [19,20]. Studies showed beneficial effects on NAFLD-related parameters in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. “Pioglitazone is currently the drug with the best evidence,” said Dr. Karrasch [23]. Among other findings, a meta-analysis of eight randomized clinical trials involving 516 patients with biopsy-proven NASH found that thiazolidinedione therapy (rosiglitazone or pioglitazone) was associated with improved fibrosis grade and NASH reduction. This effect was also seen in patients without diabetes [21]. In addition, recent studies provide evidence that GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1) agonists such as liraglutide and SGLT-2 (sodium dependent glucose transporter 2) inhibitors can reduce liver fat content in NAFLD and type 2 diabetes [2]. The practice recommendations of the German Diabetes Society (DDG) summarize effects of various interventions on NAFLD and diabetes; these are shown inTable 1 [2].

Congress: DGIM Annual Conference 2021

Literature:

- German Center for Diabetes Research, www.dzd-ev.de/forschung/ursachen-und-behandlung-der-nicht-alkoholischen-fettlebererkrankung-nafld/index.html, (last accessed 06/16/2021).

- Stefan N, et al: Diabetes and fatty liver. Diabetology 2020; 15 (Suppl 1): S156-S159.

- Roeb E, et al: [S2k Guideline non-alcoholic fatty liver disease]. Z Gastroenterol, 2015. 53(7): 668-723.

- ASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018; 69(1): 182-236.

- Tomah S, Alkhouri N, Hamdy O: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: where do diabetologists stand? Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 6(9), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-020-00097-1

- Zaharia OP, et al: Risk of diabetes-associated diseases in subgroups of patients with recent-onset diabetes: a 5-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019; 7: 684-694.

- Simeone JC, et al: Clinical course of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an assessment of severity, progression, and outcomes. Clin Epidemiol 2017(9) 679-688.

- AWMF: Consultation version of the S3 guideline “Diagnostics and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma and biliary carcinomas”, www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de (last accessed 16.06.2021).

- Hirsova P, Gores GJ : Death receptor-mediated cell death and proinflammatory signaling in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 1: 17-27.

- Roeb E, Geier A: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) – current treatment recommendations and future developments. Z Gastroenterol 2019; 57(4): 508-517.

- Heitmann J, et al: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and psoriasis – is there a common proinflammatory network? JDDG 2021; 19(4): 517-529.

- Sterling RK, et al: Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatol 2006; 43(6): 1317-1325.

- Weiß J, Rau M, Geier A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: epidemiology, clinical course, investigation, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 447-452.

- Dowman JK, Tomlinson JW, Newsome PN: Systematic review: the diagnosis and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33: 525-540.

- Rau M, Geier A: An update on drug development for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease – from ongoing clinical trials to future therapy. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology 2021; 14(3): 333-340.

- Roeb E: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: fatty liver with complications | PZ – Pharmazeutische Zeitung (pharmazeutische-zeitung.de), https://www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/ausgabe-342018/fettleber-mit-komplikationen/, (last accessed 16.06.2021).

- Rau M, Geier A: Liver Disease, Nonalcoholic Fatty. In: Kuipers E: Encyclopedia of Gastroenterology.2nd Edition. Oxford: Academic Press, Elsevier 2020: 408-413.

- Zelber-Sagi S, et al: Predictors for incidence and remission of NAFLD in the general population during a seven-year prospective follow-up. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 1145-1151.

- Stefan N, Häring HU, Cusi K: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: causes, diagnosis, cardiometabolic consequences, and treatment strategies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019; 7: 313-324.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia 2016; 59: 1121-1140.

- Musso G, et al: Thiazolidinediones and Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(5): 633-640.

- Eslam M, et al: A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 2020; 73(1): 202-209.

- Karrasch T: NASH/NAFLD from an endocrinologic-diabetologic perspective. PD Thomas Karrasch, MD. DGIM Annual Meeting, 20.04.2021.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(3): 45-46 (published 6/29-21, ahead of print).