In July, the Alzheimer’s Association held its first international congress (AAIC 2016). More than 5000 experts and researchers from 70 countries gathered in Toronto to share news and study results on Alzheimer’s dementia. We report four studies.

Does social work protect against dementia?

White matter hyperintensities (WWS) are markers of cerebrovascular disease. Often, such hyperintensities are associated with Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), and they may indicate an increased risk for cognitive decline. In turn, gainful employment with high complexity increases cognitive reserve and may protect against the development of dementia. But is there a link between cervical spine, cognitive reserve, and risk for dementia? Researchers at the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center explored this question. They examined 284 healthy subjects by MRI to detect cervical spine (median age 60 years, ± 6.42 years). In addition, the cognitive abilities of the participants were examined, and they were questioned in detail about gainful employment over the course of their lives. Gainful employment was classified according to complexity – distinguished between work primarily with people, data or things. The analysis showed that individuals who performed complex work with people were able to “endure” more cervical spine without experiencing cognitive loss. For people who worked more with data or things, this preventive function of work was not demonstrable. The authors emphasize that the results of the study show the importance of social relationships, even at work, in building resilience to AD.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI: common and distressing

Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) may also experience neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), such as apathy, mood swings, or impulse control disorders. NPS in MCI are associated with more rapid progression to dementia. But how common are such NPS really, and how burdensome are they for family members of individuals with MCI? In a Canadian study, 282 consecutive patients from a memory clinic who suffered from subjective cognitive decline or diagnosed MCI were examined [2]. Neuropsychiatric disorders were present in 81.6% of patients. Mood swings/affective disorders/anxiety were the most common (77.8%), followed by impulse control disorders/agitation (64.4%), apathy/drive disorders (51.7%), social behavior disorders (27.8%), and psychotic symptoms (8.7%). Frequency showed no differences in age, sex, or scores on the Mini-Mental Status Test. Authors’ conclusion: NPS are highly prevalent in predementia syndromes and are associated with greater burden on family members.

New checklist for behavioral disorders

A group of experts from the Alzeimer’s Association recently indicated that Mild Behavioral Impairment (MBI, defined as NPS occurring at older ages) may be a precursor to cognitive decline and the development of MCI or dementia. Older people with NPS but normal cognition are at higher risk for dementia development – indicating that NPS probably represent the early manifestation of neurodegeneration. However, the questionnaires commonly used to screen for NPS are targeted at people who already have dementia and are not suitable for use with younger people or those who do not (yet) have dementia. However, early diagnosis of NPS would be important.

This problem was addressed by a research group from Canada. The authors of the study presented at AAIC 2016 developed an MBI checklist [3]. This is based on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-C), but adapted to a younger, more independent, predementia population and supplemented with appropriate questions. Symptoms from the five categories apathy/drive/motivation, mood/affect, impulse control/agitation, social behavior, and thoughts/perception are asked. The NPS must have been in place for at least six months. The MBI checklist is currently being evaluated. In the future, it should help clinicians to better detect NPS in cognitively (still) unremarkable individuals.

Alzheimer’s disease: more frequent misdiagnosis in men

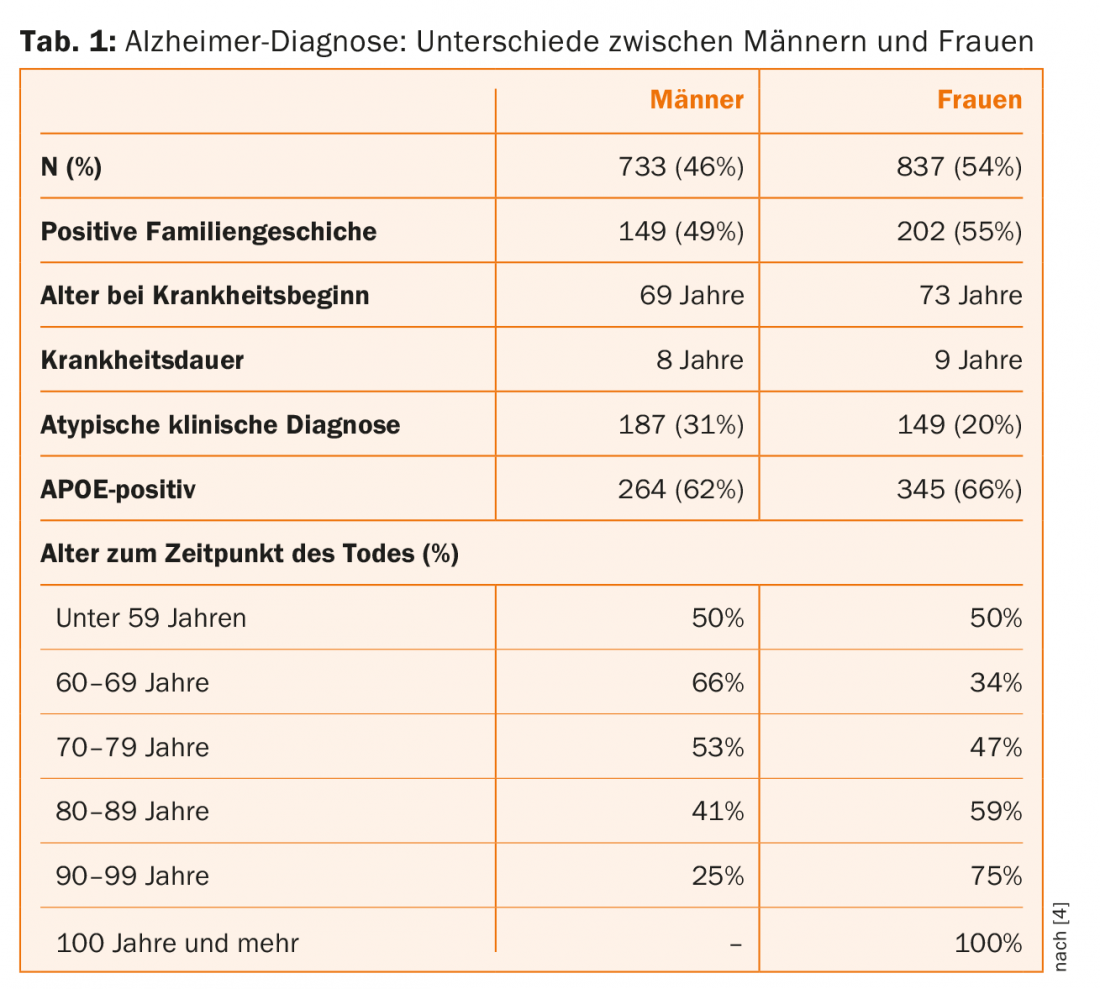

About two-thirds of all Alzheimer’s patients are women – according to neurology textbooks. However, pathological confirmation of the AD diagnosis is often lacking, and so it is not certain whether this gender distribution is true. In the present study from Florida, USA, this question was investigated [4]. The basis for the study was the Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Bank, a research-oriented network of regional institutions with the goal of examining the brains of patients diagnosed with dementia after their death and obtaining tissue material for research. The database identified 1600 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AD and recorded their demographic and clinical characteristics, including age at diagnosis, education, family history, disease duration, and genetic markers.

Women had less education overall than men and were older at the time of death. Men were younger than women at the time of diagnosis, they had a shorter duration of the disease, and they suffered more frequently from atypical manifestations (e.g., corticobasilar degeneration or aphasia) (Table 1). The genetic markers were the same in both sexes. Among women, the frequency of diagnosis increased up to age 70 and decreased thereafter. In men, the curve was opposite: the frequency of diagnosis decreased between the ages of 49 and 70, and increased significantly thereafter. The authors conclude from these results that AD is probably equally common in men and women, but that the timing of diagnosis (age) differs. Men are more likely to have an atypical course of the disease, so it stands to reason that they are also more likely to be undiagnosed with AD.

Source: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, July 22-28, 2016, Toronto.

Literature:

- Boots E, Okonkwo O, et al: Occupational Complexity, Cognitive Reserve, and White Matter Hyperintensities: Findings from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Presentation AAIC 2016, Toronto, ID O3-05-01.

- Zahinoor I, et al: Prevalence of Mild Behavioral Impairment (MBI) in a Memory Clinic Population and the Impact on Caregiver Burden. Presentation AAIC 2016, Toronto, ID 11588.

- Zahinoor I, et al: The Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist (MBI-C): A New Rating Scale for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms As Early Manifestations of Neurodegenerative Disease. Presentation AAIC 2016, Toronto, ID O1-13-03.

- Murray M, et al: Alzheimer’s Disease May Not be More Common in Women; Men May be More Commonly Misdiagnosed. Presentation AAIC 2016, Toronto, ID O3-04-04.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(5): 46-47.