There are several pathophysiologically as well as clinically relevant associations between neurovascular disease and migraine. From this perspective, they represent two sides of the same coin, and both sides should be recognized and considered in the diagnosis and treatment of migraine patients.

There are several pathophysiologically as well as clinically relevant associations between neurovascular disease and migraine. From this perspective, they represent two sides of the same coin, and both sides should be recognized and considered in the diagnosis and treatment of migraine patients. In the following, we would like to provide an overview of the relevant interactions and their clinical implications.

Headaches in general, as well as migraine in particular, are among the most common neurological disorders, with a lifetime prevalence of about 15% for migraine [1]. There is a multifaceted and sometimes complex association of migraine with neurovascular disease [2,3]. This is especially true for microvascular damage in the sense of cerebral microangiopathy. Cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is clinically relevant in the context of neurovascular disease for many reasons: it is a frequent cause of ischemic stroke as well as intracerebral hemorrhage due to its association with arterial hypertension. In addition, it represents the most common basis of vascular cognitive disorders up to the development of vascular dementia. Evidence of microvascular changes is also found in migraine.

Microvascular changes

Knowledge of this derives not least from the monogenically inherited stroke disease CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukencephalopathy). This is not only associated with microangiopathic strokes, but also with migraine in more than one third of patients, especially at younger ages [4,5]; migraine, usually with aura, is often the first symptom of the disease, with atypical or isolated aura symptoms being characteristic. Typical microangiopathic ischemic medullary lesions (“white matter hyperintensities”/WMH) are found on imaging in this disease, which is the most common hereditary form of stroke [6].

However, the occurrence of ischemic medullary lesions is not unique to migraine in the context of this inherited microangiopathy. Studies have repeatedly shown that even in common sporadic migraine, medullary lesions in the sense of WMH are sometimes found, even if predominantly in a much less pronounced form [7–9].

This was particularly demonstrated in the so-called CAMERA study [7,8], in which a migraine-associated occurrence of deep WMH was found in affected migraine patients. As a further link between neurovascular damage and migraine, ischemic-looking T2 lesions were also seen in migraine, particularly in the vertebrobasilar supply area, which are referred to as infarct-like lesions. These were found – especially in migraine with aura – more than five times more frequently than in healthy controls and, interestingly, were associated with increased attack frequency. Pathophysiologically, migraine-associated microvascular or hemodynamic changes are discussed here. Longitudinal data from follow-up studies of the CAMERA trial, collected approximately 9 years after the original study [9], revealed evidence that these deep medullary lesions may be subject to progression in migraine, this more than in control subjects without a migraine. Against the background of the above-mentioned relationship of microangiopathy to vascular cognitive disorders, the question arises as to the clinical implications of these – partly progressive – medullary lesions on cognitive functions, among other things: however, no clear associations have been shown for this in sporadic migraine so far, which may also have to be seen in the context of the expression and lesion burden, which, as mentioned, is significantly lower in sporadic migraine than, for example, in hereditary microangiopathy. In this context, interestingly, a recent paper [10] found no increased risk of dementia in migraine patients, independent of the question of the significance of medullary lesions.

Another imaging marker for microangiopathy is cerebral microbleeds (CMB). These are found in varying degrees and distribution in heme-sensitive MRI sequences (such as SWI sequence: susceptibility weighted imaging) in approximately 30 percent of patients with cerebral microangiopathy. Interestingly, there is also evidence of an association with migraine for this marker of microvascular damage: thus, infratentorial microbleeds were found more frequently in older patients with a history of migraine, in this case more likely in migraine without aura. In addition, the co-occurrence of microbleeds and strokes was found more frequently in patients with migraine [11].

Pathophysiology

Regarding the pathophysiology of microvascular disturbances in sporadic migraine, there are several potential explanations: MR spectroscopic studies of the medullary lesions, for example, suggest axonal glial damage as well as disturbances in cellular energy metabolism [12]. Overall, the pathogenesis is not conclusively understood and is probably complex: various pathophysiological bases of vascular-impressive lesions in migraine are discussed, this includes microvascular disturbances (cerebral hypoperfusion, impaired vasoreactivity, damage to the vascular endothelium), thromboembolic mechanisms and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Ultimately, these different mechanisms may yield future clues to other – non-MRI-based – disease markers in migraine, such as blood-based biomarkers, as already suggested in some studies [13,14]. Reliable biomarkers as markers of differential diagnosis, disease activity, or even prognostic assessment or stroke risk in migraine would be desirable, not least because even today the diagnosis of migraine is based purely on clinical history according to the diagnostic criteria of the International Headache Society (IHS) [15].

Increased risk for other vascular diseases

In addition to the link between migraine and microvascular disorders, there are many other links, e.g., epidemiological, clinical, or even genetic-pathophysiological. Three large meta-analyses, among others, have examined the association between migraine and ischemic stroke [16–18] and have shown a robustly increased risk of stroke in migraine, particularly in migraine with aura. In addition, a study [19] shows an association between migraine and other vascular phenotypes (myocardial infarction and peripheral arterial disease). Furthermore, attacks of migraine with aura can lead directly to a stroke, which is called a migrainous infarction [15], a rather rare and controversial entity.

Clinically significant is that severe attacks of migraine with aura (e.g., with motor or other severe aura symptoms), especially in the first manifestation, can mimic the presence of stroke (stroke mimic). Conversely, cerebral ischemia can mimic the presence of a migraine attack and, in particular, trigger the occurrence of symptomatic migraine attacks in the presence of underlying migraine susceptibility [20]. Therefore, special caution should be exercised in patients with known migraine and symptoms unknown to them or new focal neurologic deficits. Apart from that, according to recent data, headache in general seems to be a rather underestimated symptom in the context of acute cerebral ischemia [21].

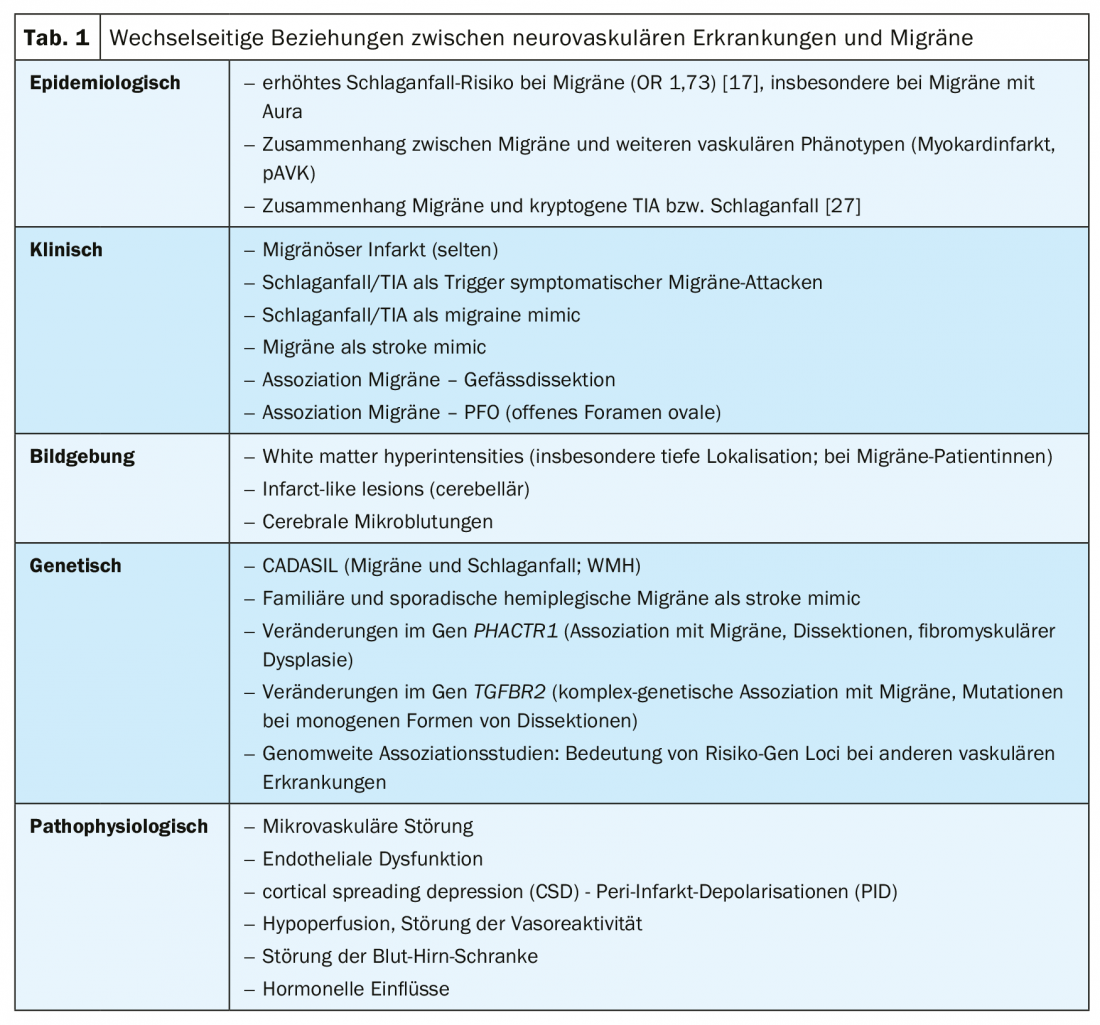

Finally, the relationship between migraine (especially without aura) and vascular dissection should be mentioned in this context [22,23]. Against the background of current genetic studies – the association of a genetic alteration in the gene PHACTR1 on the one hand with migraine [24], but on the other hand also with dissections [25] and other vascular phenotypes (e.g. myocardial infarction or fibromuscular dysplasia) – this also has a pathophysiological significance. Here, there is evidence of endothelial dysfunction [26]. A listing of the complex interrelationship between neurovascular disease and migraine at the different levels can be found in Table 1.

Take-Home Messages

- There is a multifaceted interrelationship between migraine and neurovascular, particularly microvascular, disorders that is relevant to the clinical management of migraine patients.

- Migraine (especially with aura) is a typical early symptom in CADASIL hereditary microangiopathy. This should be considered as a differential diagnosis when atypical aura symptoms are present, there are marked medullary changes (WMH), or there is a positive family history of migraine, stroke, or dementia.

- An increased prevalence of WMH is found in sporadic migraine, especially in women. These sometimes show themselves to be progressive over time. Knowledge of this is important, among other things, for the differential diagnosis of inflammatory changes, e.g., in the context of MS in younger patients.

- The clinical relevance of WMH in migraine has not been conclusively clarified to date; affected individuals should not be unnecessarily confused.

- In addition to WMH, cerebellar a.e. ischemic lesions are frequently found in migraine (especially with aura), which may be related to the pathophysiology and the especially occipital occurrence of migraine auras (in terms of visual auras).

- Migraine as a clinically usually episodic disease thus also exhibits “chronic” features.

- Migraine – especially with aura – is associated with an increased risk of stroke.

- True migrainous infarcts are probably rare. Strokes can trigger migraine auras.

- There is an epidemiologic, genetic, and pathophysiologic association between migraine and dissections of brain-supplying vessels.

Literature:

- Stovner Lj, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al: The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007; 27: 193-210.

- Freilinger C, Schubert V, Auffenberg E, Freilinger T: Migraine and vascular diseases. The Neurologist & Psychiatrist 2016; 17: 38-46.

- Malik R, Winsvold B, Auffenberg E, et al: The migraine – vascular disease connection: a genetic perspective. Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 658-668.

- Vahedi K, Chabriat H, Levy C, et al. Migraine with aura and brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in patients with CADASIL. Arch Neurol 2004; 61: 1237-1240.

- Guey S, Mawet J, Hervé D, et al: Prevalence and characteristics of migraine in CADASIL. Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 1038-1047.

- Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, et al: CADASIL. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 643-653.

- Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, et al: Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. Jama 2004; 291: 427-434.

- Kruit MC, Launer LJ, Ferrari MD, et al: Infarcts in the posterior circula- tion territory in migraine. The population-based MRI CAMERA study. Brain 2005; 128: 2068-2077.

- Palm-Meinders IH, Koppen H, Terwindt GM, et al: Structural brain changes in migraine. JAMA. 2012; 308: 1889-1897.

- George KM, Folsom AR, Sharrett AR, et al: Migraine Headache and Risk of Dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study. Headache 2020 May; 60 (5): 946-53.

- Arkink EB, Terwindt GM, de Craen AJ, et al: PROSPER Study Group. Infratentorial Microbleeds: Another Sign of Microangiopathy in Migraine. Stroke. 2015; 46: 1987-1989.

- Erdélyi-Bótor S1, Aradi M, Kamson DO, et al: Changes of migraine-related white matter hyperintensities after 3 years: a longitudinal MRI study. Headache. 2015; 55: 55-70.

- Liman TG, Bachelier-Walenta K, Neeb L, et al: (2015). Circulating endothelial microparticles in female migraineurs with aura. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache, 35(2), 88-94.

- Pescini F, Donnini I, Cesari F, et al: (2017). Circulating biomarkers in Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy Patients. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases: the official journal of National Stroke Association, 26(4), 823-833.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2013). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache, 33(9), 629-808.

- Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC et al. Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Bmj 2005; 330: 63

- Schurks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, et al: Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 2009; 339: b3914.

- Spector JT, Kahn SR, Jones MR et al. Migraine headache and ischemic stroke risk: an updated meta-analysis. Am J Med 2010;123: 612-624.

- Bigal ME, Kurth T, Santanello N, et al: Migrai- ne and cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Neurology 2010; 74: 628- 635

- Olesen J, Friberg L, Olsen TS, et al: (1993). Ischaemia-induced (symptomatic) migraine attacks may be more frequent than migraine-induced ischaemic insults. Brain: a journal of neurology, 116 (Pt 1), 187-202.

- Harriott KA (2020): Headache after ischemic stroke. Neurology 94 (1) e75-e86;

- Rist PM, Diener HC, Kurth T, et al: Migraine, migraine aura, and cervical artery dissec- tion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 2011; 31(8): 886-896.

- Metso TM, Tatlisumak T, Debette S, et al: Mi- graine in cervical artery dissection and ischemic stroke patients. Neurology 2012; 78(16): 1221-1228. dissections.

- Freilinger T, Anttila V, de Vries B, et al: International Headache Genetics Consortium (2012). Genome-wide association analysis identifies susceptibility loci for migraine without aura. Nature genetics, 44(7), 777-782.

- Debette S, Kamatani Y, Metso TM, et al: Common variation in PHACTR1 is associated with susceptibility to cervical artery dissection. Nat Genet. 2015;47(1):78–83. doi:10.1038/ng.3154

- Gupta RM, Hadaya J, Trehan A, et al: (2017). A Genetic Variant Associated with Five Vascular Diseases Is a Distal Regulator of Endothelin-1 Gene Expression. Cell, 170(3), 522-533.e15.

- Li L, Schulz UG, Kuker W, et al: Oxford Vascular Study (2015). Age-specific association of migraine with cryptogenic TIA and stroke: population-based study. Neurology, 85(17), 1444-1451.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(4): 6-9.