Ovarian cancer is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage and has an unfavorable prognosis. Maximal cytoreductive surgery, if possible, is the first priority therapeutically and prognostically, followed by platinum-containing chemotherapy. In stages III-IV without planned reoperation, the addition of bevacizumab to initial chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy has been approved for several months. The same applies to the therapy of platinum-sensitive recurrences. The newest indication approved is bevacizumab for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer after a maximum of two prior therapies with monochemotherapy. Women with genetically induced ovarian cancer are treated the same as patients with sporadic tumors, but now have the option of maintenance therapy with olaparib in the relapsed setting.

Ovarian cancer is the second most common carcinoma from the gynecologic field and is the most likely of these cancers to lead to death. In Switzerland, it affects about 600 women per year (3% of all cancers). The average age at diagnosis is 63 years, and 14% of women are younger than 50 years. 90% of ovarian cancers are tumors of epithelial origin, while the others are tumors of the germ cells, stroma, or sarcomatoid or small cell neoplasms. WHO divides epithelial carcinomas into six histologic classes. Serous carcinomas are the most common (about 80%), and they can range from mild to very aggressive.

Diagnosis and risk factors

The symptoms that often precede the diagnosis are nonspecific: abdominal pain, abdominal tightness, micturition difficulties and, in the course, an increase in abdominal girth or menstrual irregularities. Risk factors include the number of ovulations (the more ovulations, the higher the risk), endometriosis, polycystic ovaries, and a BRCA 1 or 2 gene. In contrast, births, breastfeeding, oral contraception, tubal ligation, and hysterectomy reduce risk.

Diagnosis usually occurs at an advanced stage (FIGO III and IV), which means that only about 15% of ovarian cancers are confined to only one ovary. Prognostic factors include stage, histology, and surgery that is as complete as possible. Unfortunately, the prognosis of ovarian cancer as a group remains poor, with only about 40% of patients with FIGO III stage (metastasis outside the pelvis but intra-abdominal) and only about 19% with FIGO IV stage (distant metastasis) surviving five years; these data predate modern therapeutic options (bevacizumab +/- maintenance therapy, olaparib, HIPEC).

Clarification and surgical therapy

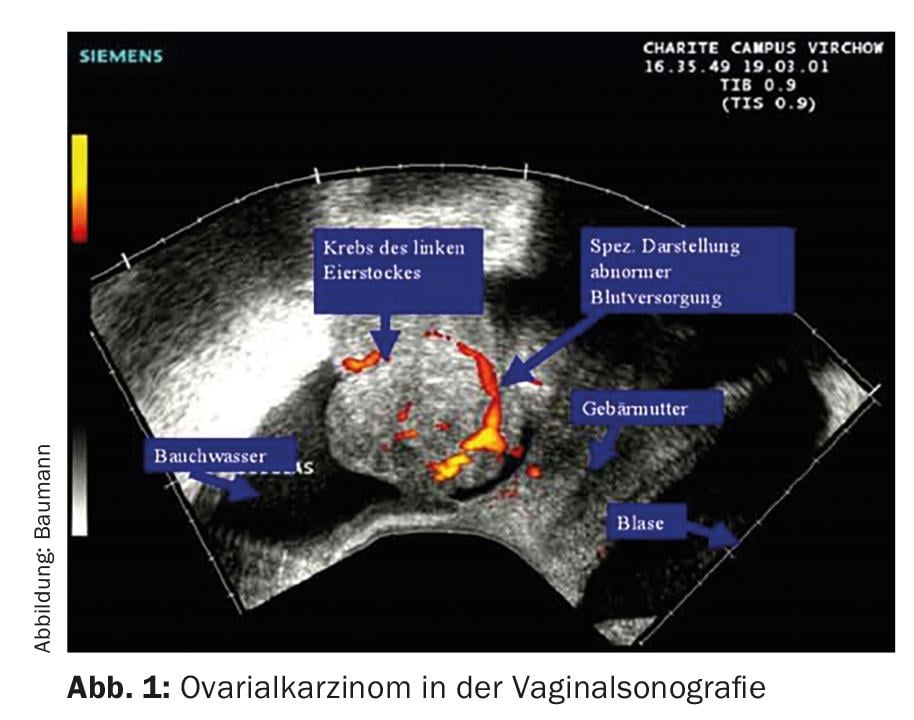

Without surgical staging or surgery, the exact extent of the disease cannot be reliably determined. In most cases, women first consult their gynecologist, who uses vaginal ultrasound to obtain a diagnosis (Fig. 1) .

If a carcinoma is suspected, this is followed by a computer tomography or a PET-CT (Fig. 2) . Determination of the tumor marker Ca 125 can also be helpful.

Surgery includes hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy, and depending on tumor extent, infracolic and infragastric omentectomy, as well as multiple targeted peritoneal biopsies. The surgeon’s experience (number of procedures performed annually) is important because the prognosis is influenced by the surgical result achieved (optimal debulking). Whenever possible, all macroscopically visible tumors should be removed, i.e., surgery requires skilled gynecologists and, in some circumstances, visceral surgeons who can perform the sometimes major abdominal procedures such as partial bowel resections, peritonectomies, etc. The therapy of advanced ovarian cancer should already be discussed preoperatively on an interdisciplinary basis, and the possible interventions or treatments should also be discussed. their consequences/morbidities must be discussed with the patients in advance. Postoperative staging is according to FIGO or TNM [1].

Therapy of the early stages (FIGO I-IIA)

Nothing has changed in the therapy of the early stages in recent years. Patients at these stages (approximately 20%) have a better prognosis (5-year survival 60-90%). Factors such as grading, capsular breakdown, unilateral or bilateral involvement, and patient age, if any, are important in deciding whether adjuvant therapy should be given. No chemotherapy is recommended for patients with stage FIGO IA, G1. In stage IB, the additional factors and optimal surgical staging are important; again, chemotherapy can often be omitted.

All other early stage patients (all stages FIGO II and/or all histologic gradings higher than 1) benefit from platinum adjuvant chemotherapy. I will not go into the discussion of whether carboplatin alone is sufficient (six cycles) or whether the carboplatin/paclitaxel combination is preferable (three cycles may be sufficient, but classically six are usually administered) here [2,3].

Therapy of advanced stages (FIGO IIB-IV)

In the advanced stages, surgery that is as complete as possible is especially important. Patients in whom no tumor is visible macroscopically have the best prognosis. If tumor must remain, those women with tumor remnants less than 1 cm have a better chance than women with tumor remnants greater than 1 cm. In patients with primarily suboptimal surgery (e.g., no interdisciplinary team – although necessary), so-called interval debulking may be useful. In this setting, three cycles of standard chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel are given first, followed by second surgery and three additional cycles of chemotherapy if there is a response.

All patients with advanced stages have been treated with six cycles of platinum-containing combination chemotherapy (usually with paclitaxel) until now. Adding more cytostatic drugs or performing more than six cycles has shown no benefit.

In 2009, a Japanese group published a paper using “dose-dense paclitaxel/carboplatin” that showed a better overall survival of 72% at three years versus 65% in the standard therapy patient group [4]. “Dose-dense” means that paclitaxel is administered weekly without a break, while carboplatin continues to be administered every three weeks. Side effects (mainly hematological) occurred slightly more frequently in the patient group treated in this way. However, there are also schemes for weekly use of both substances [5].

Therapy with Bevacizumab

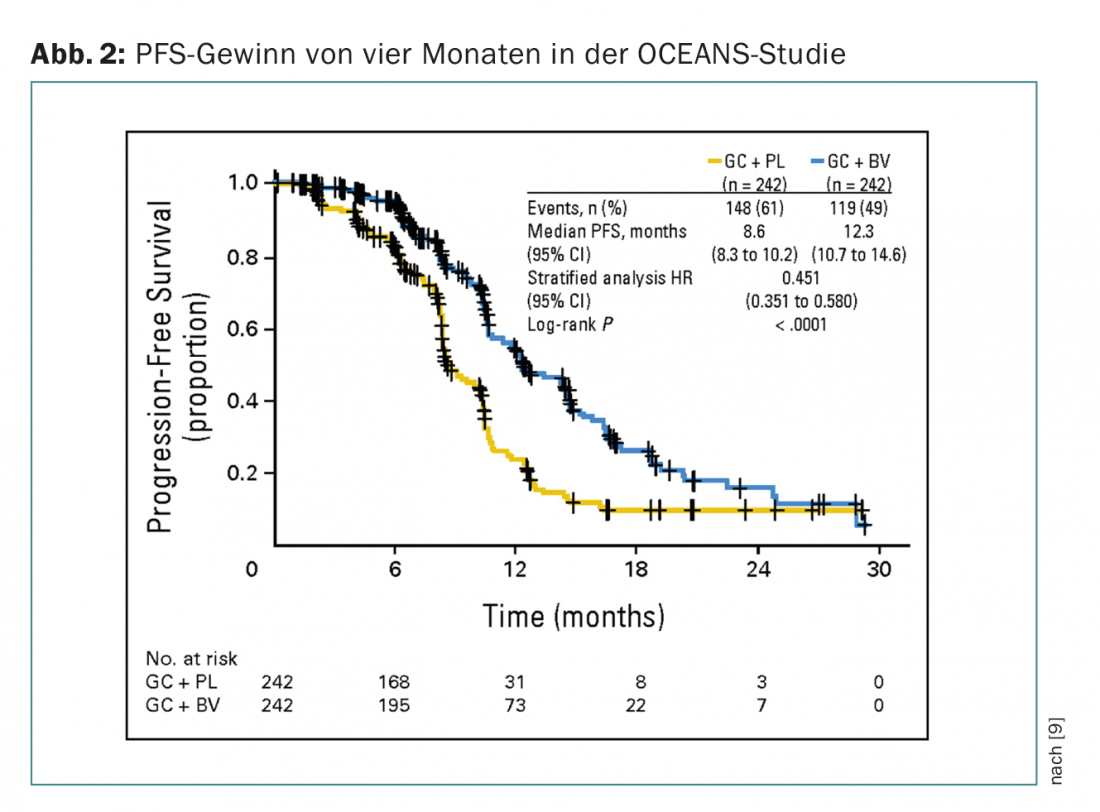

The addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy may be considered as a newer therapeutic option. Bevacizumab inhibits all isoforms of the VEGF-A receptor. There are now four large trials demonstrating the efficacy of angiogenesis inhibition in ovarian cancer (GOG 0218 and ICON7 in firstline, OCEANS and AURELIA for recurrence). Common to all studies is a 3.5-4 month improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and response rate, but not overall survival. The studies differ not only in indication and design, but also in bevacizumab dosage and duration of therapy. Angiogenesis inhibition is used in these trials not only in parallel with chemotherapy, but especially as maintenance therapy. Bevacizumab is the first maintenance therapy to show benefit.

Bevacizumab is approved in Switzerland in patients with advanced ovarian cancer (FIGO III-IV) together with carboplatin/paclitaxel in first-line therapy when no second surgery or treatment is available. an interval debulking is planned. Patients receive bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kgKG every three weeks in parallel with six cycles of chemotherapy; thereafter, bevacizumab is given as maintenance therapy every three weeks until progression or. maximum during 15 months. The side effect spectrum of bevacizumab is known from other tumor therapies: arterial hypertension, proteinuria, rarely thromboembolism and especially a slightly increased rate of intestinal perforation are to be mentioned – besides the significantly increased therapy costs.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy

As early as the 1970s, attempts were made to increase the survival of optimally preoperated patients with high local doses of chemotherapy (intraperitoneal). This very complex, time-consuming process has been continuously improved over the years. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is always given in parallel with intravenous chemotherapy. The substances in the intravenous therapy part were partially exchanged and the intraperitoneal chemotherapy with cisplatin and paclitaxel is performed heated (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, HIPEC). As before, toxicity and complications are substantial, so this therapy is not a standard of care despite the survival benefit demonstrated in individual studies, but it is increasingly used in larger centers [6]. Recently, a review of the use and benefits of intraperitoneal chemotherapy at six major centers in the United States was published [7]. Over time (2007-2012), HIPEC has been increasingly used, but according to the authors, this procedure is still used in less than 50% of eligible patients. Overall survival at three years was 81% in the HIPEC arm and 71% in the standard arm.

Recurrent therapies

Since most of the patients with advanced ovarian cancer relapse, the question of the most optimal recurrence therapy arises. For patients with a long therapy-free interval, in good general condition and with a recurrence that can be removed macroscopically in toto, a second operation is an option, although the study situation here is not very good. In exceptional cases, HIPEC is also evaluated in this situation.

The primary decision is whether the carcinoma is platinum-sensitive (relapse only after six, preferably twelve months) or -resistant. For sensitive carcinomas, the doublet carboplatin (better tolerated, equally effective as cisplatin) and paclitaxel or alternatively carboplatin/pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or carboplatin/gemcitabine can be used again. Combination therapy is again more effective than monotherapy [4]. For platinum-refractory disease (relapse before six months), non-cross-resistant drugs should be used: Gemcitabine, oral etoposide, vinorelbine, or even docetaxel and oxaliplatin. There are also data on trabectedin together with Caelyx® [8].

In relapsed situations, the addition of bevacizumab (also as maintenance therapy) has also shown a PFS benefit to an analogous extent. The OCEANS trial (phase III, PFS gain four months) included patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (Fig. 2) [9]. Chemotherapy in both arms consisted of carboplatin/gemcitabine. Bevacizumab was used in the experimental arm at 15 mg/kgKG every three weeks until progression. Patients were not allowed to be pretreated (except adjuvant) and prior anti-VEGF therapy was not allowed. In Switzerland, bevacizumab is also approved in this situation, but a cost approval must be obtained (which applies to all bevacizumab indications).

The newest indication for bevacizumab in ovarian cancer is for platinum-resistant carcinoma (AURELIA) with no more than two prior therapies without prior angiogenesis inhibitors. Treatment is given together with either topotecan, paclitaxel or Caelyx®. Dosage is 10 mg/kgKG every 14 days until disease progression. Again, the PFS gain is 3.5 months, which may be considered significant in this situation where patients otherwise survive less than 12 months. AURELIA has additionally shown improvement in quality of life. However, there are some caveats to mention with this study, especially the open-label design with cross-over possibility.

That angiogenesis inhibition plays a role in ovarian cancer (also in ascites genesis) has been known for some time. Now we can also use this therapeutic principle. However, the most optimal time is still not clear (possibly several times?), and the costs cannot be disregarded in the current situation either [10].

Therapy in BRCA 1 and 2 gene carriers

Approximately 10-15% of ovarian cancers are familial, with the two BRCA genes being the most important. A BRCA 1 carrier’s lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is 25-55%, and a BRCA 2 carrier’s lifetime risk is 10-25%. After family planning has been completed, prophylactic bilateral adnexectomy should be discussed with these patients (in addition to other preventive options).

To date, the therapy of these ovarian carcinomas does not differ from that of sporadic carcinomas, nor is the prognosis worse [11]. A maintenance therapy with olaparib should be mentioned here as an innovation.

In up to 50% of high-grade serous carcinomas, there is a defect in homologous recombination (in the germline as in BRCA carriers or somatically in tumor cells), an important pathway to correct DNA damage. PARP enzymes (polymerases) are responsible for repairing single-strand DNA breaks. In healthy cells, these are recombined homologously. However, this is not possible without a functioning BRCA gene. PARP inhibitors lead to cellular instability and cell death (“synthetic lethality”). Tumor cells are particularly susceptible to this mechanism.

A phase II trial demonstrated that maintenance therapy with the oral PARP inhibitor olaparib provides a PFS benefit in women with high-grade serous pretreated (at least two therapies, platinum-sensitive, responding to last therapy) ovarian cancer [12]. The PFS gain was mainly demonstrated in patients with BRCA-positive (germline or in tumor) disease and was still seven months in this group (HR 0.35). An OS benefit has not yet been shown. Olaparib is not yet officially approved in Switzerland, but BRCA-positive patients can be enrolled in a special program via the company. Side effects are reasonable (mainly fatigue, gastrointestinal, hematologic) and rarely of grade 3 and 4.

Initial clinical data on immune checkpoint inhibitors with anti-PD-1 and anti-PDL-1 antibodies were also presented at this year’s ASCO Congress. These “immunotherapies” – to put it simply – release the brakes of the body’s own immune system against tumor cells, and they are already being used with good success in melanoma and bronchus carcinoma. Immune checkpoint inhibitors also appear to have an effect in ovarian cancer, particularly in tumors induced by BRCA mutations.

Hopefully, the prognosis of patients with advanced ovarian cancer will soon improve with newer treatment options.

Literature:

- Cancer Staging Handbook, AJCC staging Manual7th edition 2010.

- Sandercock J, et al: First-line treatment for advanced ovarian cancer: paclitaxel, platinum and the evidence. British Journal of Cancer 2002; 87: 815-824.

- The International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group: Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclo-phosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 505-515.

- Katsumata N, et al: Dose dense paclitaxel once weekly in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 1331-1338.

- Sehouli J, et al: Weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin for patients with advanced ovarian cancer: results of a multicentre phase II study of the NOGGO. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008; 61: 243-250.

- Armstrong DK, et al: Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 34-43.

- Wright AA, et al: Use and Effectiveness of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2841-2847.

- Poveda A, et al: Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in relapsed ovarian cancer: outcomes in the partially platinum-sensitive (platinum-free interval 6-12 months) subpopulation of OVA-301 phase III randomized trial. Ann Oncol 2011; 22(1): 39-48. doi.1093/annonc/mdq352.

- Aghajanian C, et al: OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(17): 2039-2045.

- Liu JF, et al: Emerging role for bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy for patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 1287-1289.

- Rubin SC, et al: Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA1. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1413-1416.

- Ledermann J, et al: Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1382-1392.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(2): 25-28.