Peripheral arterial disease, as one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, now has a pandemic character. This development promotes technical progress and stimulates pharmaceutical research. With regard to the frequency of amputations in diabetics, unfortunately not much has changed in recent years. At the same time, 85% of amputations could be prevented. It is important to think about diabetic foot syndrome early, restore perfusion, and monitor the patient closely to detect recurrence in time. DOAKs have made pharmacological therapy and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism simpler and safer, but also more expensive. In addition, there is the approach of catheterizing acute venous thromboembolism.

Angiology is a very dynamic field that has evolved greatly in recent years – fortunately, because peripheral arterial disease (PAVD) affects 202 million people worldwide [1]. That is almost five times as many as there are HIV-positive patients worldwide. Another new aspect of this development is that there is no longer any difference in the prevalence of peripheral arterial disease worldwide. National borders, income and standard of living no longer play a role in terms of morbidity.

History, ABI measurement, and oscillogram are the minimum basic data needed to diagnose peripheral arterial disease. However, it must be remembered that two-thirds of patients with manifest pAVD have no symptoms. Routine ABI measurement in the primary care physician’s office, just as a matter of course as an ECG, is something we have been calling for for years. The goal is not to recruit as many patients as possible for therapy. Those who are symptom-free usually do not need specific vascular therapy. A pAVK is a clear indication of manifest atherosclerosis and has a similar significance to repolarization disturbances in the ECG, which indicate silent myocardial ischemia. 50% of patients with pAVD have significant coronary involvement and 43% have significant cerebral involvement [2]. To not diagnose pAVD is to miss a preventive approach in these patients.

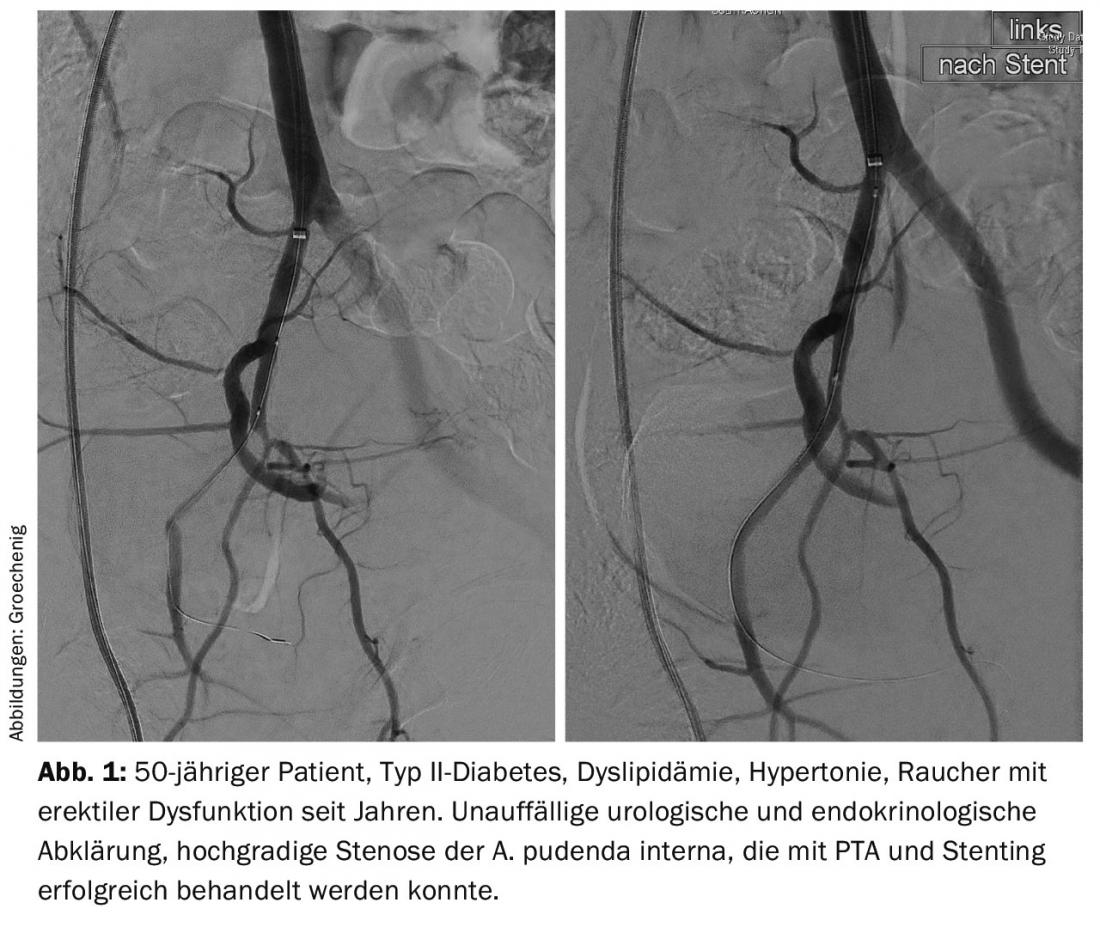

Erectile dysfunction: I would also like to point out an important risk factor that is often not detected. Erectile dysfunction affects up to 50% of men, depending on their age. Strikingly, there was a significant association between diabetes, hypertension, smoking, obesity, and dyslipidemia, precisely the classic risk factors for atherosclerosis. 50% of men with acute coronary syndrome have erectile dysfunction, and in 70% erectile dysfunction is a harbinger of acute coronary syndrome and precedes the coronary event by an average of three years [3]. Thus, erectile dysfunction is an important biomarker of atherosclerosis that warrants increased attention. But honestly, who asks about this in practice during a consultation?

In addition to the preventive approach to preventing a cardiovascular event, there are also real therapeutic options. In Aarau, we have established a consultation for erectile dysfunction together with the urology department and endocrinology since January 2015. If urological, hormonal or other disorders have been ruled out, it is not uncommon to find a disturbed blood supply, which today can be treated by catheterization (Fig. 1).

Early detection, prophylaxis and diagnostics

Of course, early detection programs would be optimal to identify people with early, still reversible vascular damage and to create a preventive approach here primarily through lifestyle changes. Unfortunately, the studies on intima-media thickness measurement, “arterial stiffness,” pulse wave velocity, or FMD of the brachial artery, which were so highly praised a few years ago, are not viewed as euphorically today as they were at the time of publication.

It is important to be aware that most patients with pAVD die from other manifestations of atherosclerosis, especially myocardial infarction and stroke. And this could be prevented today by modern drug therapy. How efficient, for example, intensified secondary prophylaxis can be is shown in studies on the therapy of asymptomatic carotid stenosis, where the stroke rate could be reduced with antiplatelet drugs, ACE inhibitors, and statins <1% and was thus much lower than with therapeutic interventions, regardless of whether catheterization or surgery was used [4].

The primary care physician has a crucial role in detecting a disease that is often asymptomatic, in educating the patient, in promoting lifestyle changes and compliance, and, most importantly, in assessing the right time to entrust the patient to a specialist.

Duplex sonography has evolved in recent years with much more powerful equipment, new probes, and contrast-enhanced sonography to such an extent that angiography is virtually no longer performed for the diagnosis of PAOD. In the vast majority of cases, treatment planning is possible with the aid of duplex sonography, and intra-arterial angiography as basic diagnostics is then performed as part of an interventional procedure, which saves considerable time, costs, and resources.

Therapy: Open questions and new developments

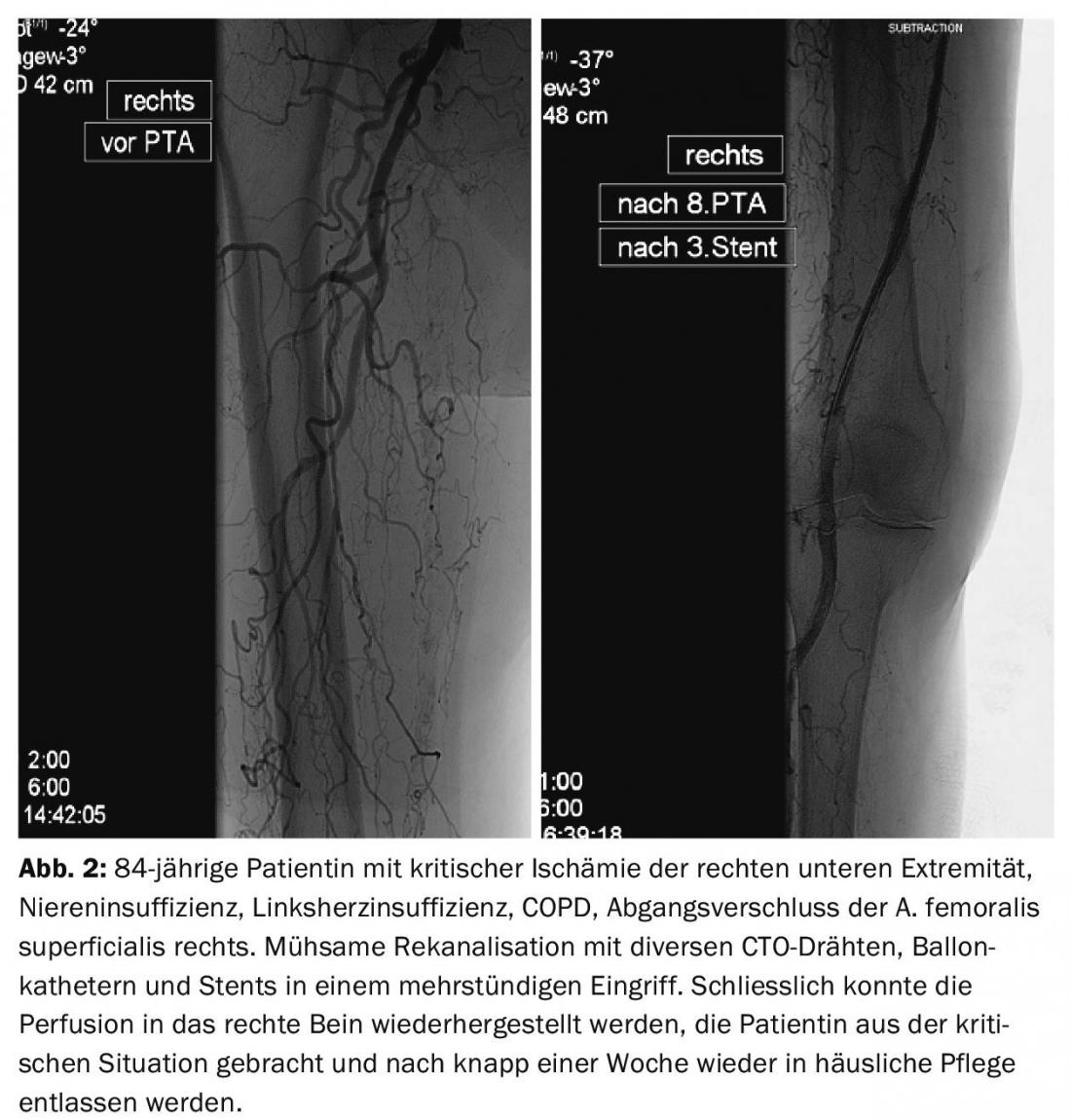

Therapeutically, catheter-based procedures are now the primary treatment for PAOD. The development of refined wires, re-entry devices [5], ultra-thin, lubricated balloon catheters, atherectomy devices, lysis and aspiration catheters allows interventions that were considered impossible a few years ago (Figs. 2 and 3).

As a result, interventional procedures have become much more demanding and require significantly more time and resources, which are not or only inadequately reflected in the current reimbursement structure. This leads to considerable cost pressure on hospitals with a center function.

The problem today is not so much recanalizing long-standing occlusions, but rather keeping them open for extended periods of time. Many questions remain unanswered: “Platelet inhibition with monotherapy or dual?”, “Anticoagulation?”, “If so, with what?” etc. Large randomized studies similar to those in cardiology practically do not exist, so that we have to stick to the unfortunately not completely transferable model of cardiology. After all, a few years ago an expert opinion [6] was published that can be used as a guide. Successful relapse prophylaxis always buys into an increased bleeding propensity, but fortunately something is happening here as well: the development of new platelet inhibitors is on the way. The first active ingredient approved by the FDA is vorapaxar. These substances act specifically at those sites where their effect is needed [7] – i.e. where platelets are activated due to an intimal lesion, these are selectively blocked. Fibrin, which is important in hemostasis, is not affected. This gives an additional better efficacy with greater therapeutic safety.

Diabetic foot syndrome

I would love to tell you something new about this, especially since the WHO launched a program ten years ago with the goal of reducing the frequency of amputations in diabetics by 50% [8]. Worldwide, one amputation is performed on a diabetic patient every 30 seconds. 12-25% of diabetics develop diabetic foot syndrome. A foot ulcer in a diabetic means a 24 times higher risk of amputation. When WHO conducted a target review ten years after the program was initiated as mentioned above, it found that nothing had changed. And that’s sky-scraping, because 85% of amputations would be preventable!

In diabetics, a specific situation is found from the interaction of many factors that are potentiated and often underestimated. Affected individuals often demonstrate not only isolated critical ischemia but also additional neuropathy, pressure lesion, and infection. In addition, diagnosis is more difficult: On the one hand, ABI values are falsely high due to mediasclerosis. Second, the pulse may appear to be palpable, but in reality it is only a stop pulse with the artery occluded proximally, or the patient may show no symptoms.

Patients with diabetic foot syndrome belong immediately in a center that has all specialist departments available around the clock. In more than 50% of affected patients, pAVK is found. The minimum goal is to open at least one vessel – if it is possible to open several vessels, all the better. However, the number of reopened arteries has no influence on the leg preservation rate [9]. The openness rate over 36 months also has no influence, often second interventions are necessary to improve the patency rate [10]. It is important to think about it early, aggressively restore perfusion by all means, and then monitor the patient closely to detect recurrence in time and improve the openness rate with further intervention if necessary.

Venous thromboembolism

With regard to pharmacological therapy, the new direct anticoagulants (DOAKs) have made therapy simpler and safer, but also more expensive. The four DOAKs approved in Switzerland (Tab. 1) differ in their indications, doses, and limitations of use. What they all have in common is that an antidote is (still) lacking and that they are not approved for use in impaired renal function. The latter only because it has not been studied. Patients with impaired renal function were simply not included in the studies.

Not entirely new, but increasingly on the rise, is the approach of addressing acute venous thromboembolism by catheterization. Local lysis should reduce thrombus burden and pulmonary embolism risk, unmask any anatomic obstructions as in May-Turner syndrome, and most importantly reduce the incidence of postthrombotic syndrome. However, large multicenter studies are still ongoing here, so that no definitive recommendation can be made at the present time.

I hope that with this brief overview I have been able to give you an insight into current developments in a highly interesting and very dynamic subject. I will be happy to answer your questions, suggestions or criticism personally.

Literature:

- Fowkes GR, et al: Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. The Lancet 2013; 382: 1329-1340.

- Marsico F, et al: Prevalence and severity of asymptomatic coronary and carotid artery disease in patients with lower limbs arterial disease. Atherosclerosis 2013; 228: 386-389.

- Montorsi F, et al: Erectyle dysfunction, prevalence, time of onset and association with risk factors in 300 consecutive patients with acute chest pain and angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Eur Urol 2003, 44; 360-365.

- Spence JD, Hackam DG: Treating arteries instead of risk factors. A paradigm change in management of atherosclerosis. Stroke 2010; 41: 1193-1199.

- Langhoff R, et al: Successful revascularziation of chronic total occlusion of lower extremity arteries: a wire only and bail out use of re-entry device approach. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2013 Oct; 54(5): 553-559.

- Jäger KA, et al: Swiss consensus on antiplatelet therapy in angiology. Schweiz Med Forum 2009; 9(39): 690-693.

- Morrow DA, et al: Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1404-1413.

- Boulton AJ, et al: The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005; 366: 1719- 1724.

- Iida O, et al: Importance of the angiosome concept for endovascular therapy in patients with critical limb ischemia. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2010; 75(6): 830-836.

- Romiti M, et al: Meta-analysis of infrapopliteal angioplasty for chronic critical limb ischaemia. J Vasc Surg 2008 May; 47(5): 975-981.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(11): 8-12