If giant cell arteritis is suspected, further evaluation and treatment should be undertaken immediately. Typical symptoms such as headache or chewing pain and visual disturbances may be absent. Oligosymptomatic RZA can be diagnosed with imaging. Temporal artery biopsy is the diagnostic gold standard. The IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab (Actemra) is very effective in treating steroid-refractory patients and will be used more frequently – and likely as first-line therapy – in the future.

Historically, we understand giant cell arteritis (RZA) to be Horton’s disease or arteritis temporalis, which is autoimmune inflammation of the temporal artery. Cranial symptoms may occur such as headache and chewing pain, visual disturbances such as anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION), or stroke, accompanied by a systemic inflammatory response. This is also consistent with the American Rheumatology Society (ACR) classification criteria for RZA established over 25 years ago: age >50 years, new onset headache, ESR >40 mm/1h, abnormal temporal artery (absent pulse, indurated artery), and evidence of transmural inflammation on temporal artery biopsy. These criteria, mind you, are intended to classify patients for study purposes and not as diagnostic criteria.

Case 1 is a typical patient. In addition, these patients may experience other ischemic symptoms such as chewing pain, sensitive scalp, visual disturbances (foggy vision, double vision). Concomitant polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and/or general symptoms are possible.

However, with the development and wider availability of diagnostic methods such as ultrasound, MRI, and PET-CT, we are increasingly enrolling patients with evidence of vasculitis of the great vessels without involvement of the temporal artery and without cranial symptoms. This expands the spectrum of diseases diagnosed. As illustrated with case 2, the clinical presentation can vary significantly. In particular, the aforementioned ACR criteria are inadequately or not met by many of these patients.

Clarification of “classic” arteritis temporalis

If a patient presents to your practice as case 1, the diagnosis of RZA is obvious. Rapid treatment with high-dose cortisone to prevent irreversible visual loss or stroke is critical in this situation. If the patient responds quickly and well to these, one is often tempted to dispense with further diagnostics. Although this may be straightforward in some cases, it is recommended that definitive diagnosis be sought for several reasons.

Insufficient specificity of many RZA symptoms: The often cited example of the 70-year-old flu patient shows that myalgias, headaches, and/or an inflammatory reaction do not constitute vasculitis. Also, excellent symptom response to cortisone treatment is suggestive but not specific for RZA. PMR, which shares many of the symptoms with RZA, or other inflammatory systemic diseases, also respond to higher doses of prednisone. Uncertainties regarding the definitive diagnosis or the further course of action are then not uncommon. Unfortunately, diagnostics are often unproductive at this point because patients have already been on prednisone treatment for some time, which makes interpretation of the examinations difficult or even impossible.

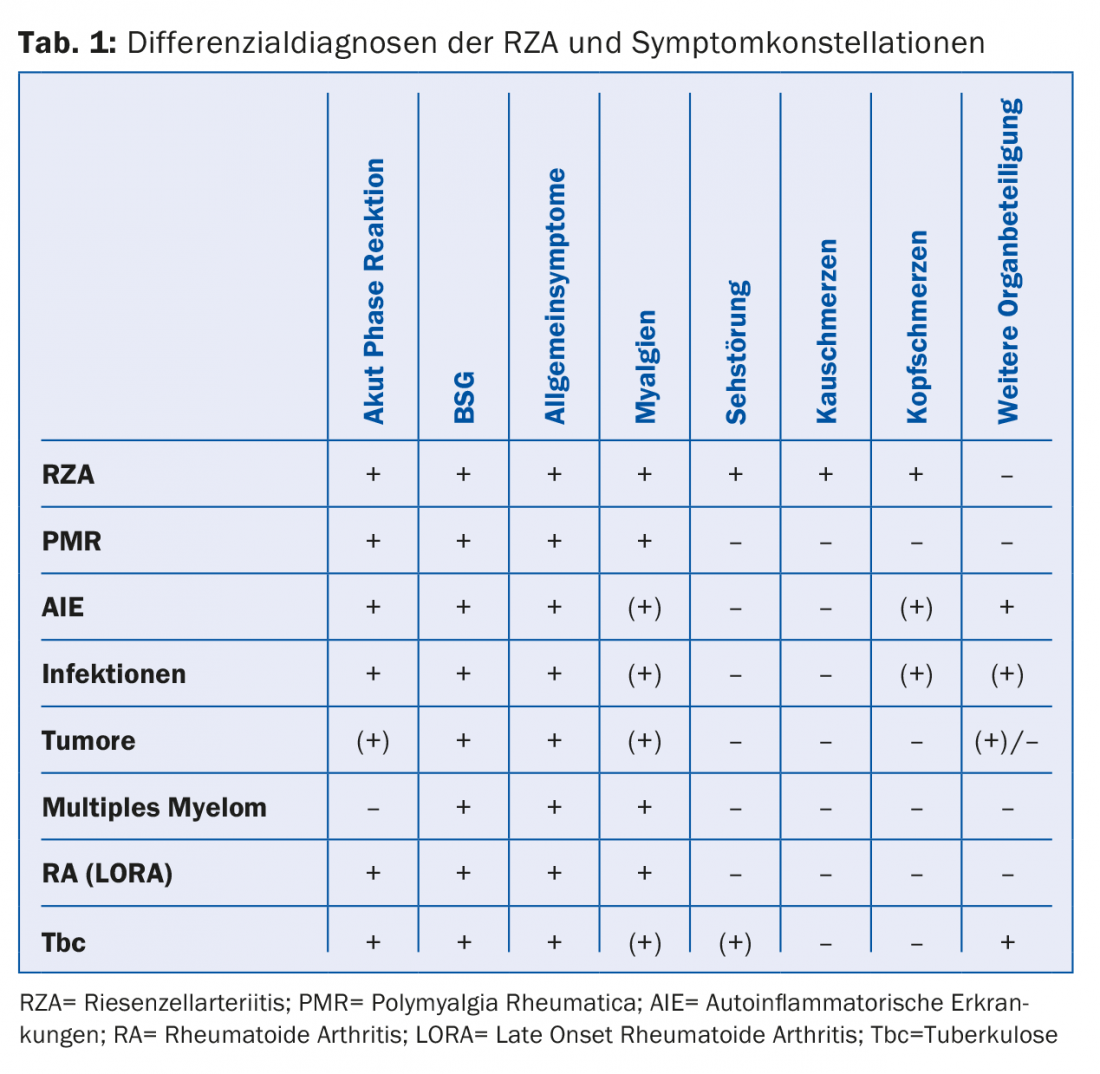

On the other hand, we must avoid unnecessarily long, intensive cortisone treatments. Ultimately, the exclusion of possible differential diagnoses (Tab. 1) can be costly and not justified in every case.

Due to the necessity of a rapid start of therapy in case of cranial symptoms, further diagnostics should also ideally be performed within 24 hours, as the sensitivity of the test methods decreases significantly after a few days of treatment. Fast-track clinics, to which primary care providers can refer patients on an emergency basis for rapid diagnosis in the event of a suspicion, are increasingly being established at central hospitals.

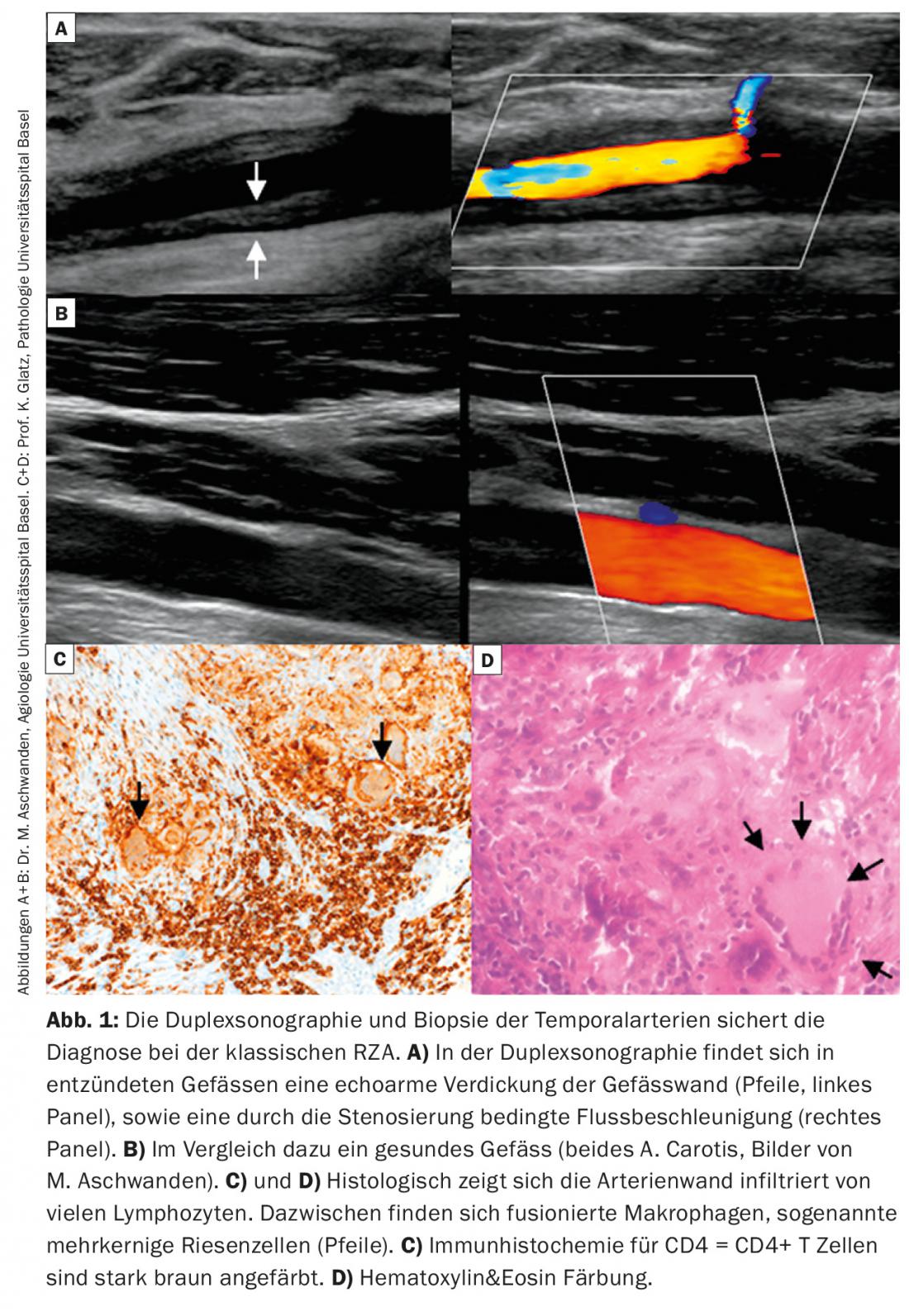

Ultrasound examination: an ultrasound examination of the temporal artery is often performed. This has very good sensitivity (88%) and specificity (97%) for the diagnosis of temporal arteritis [1]. In addition, imaging of the carotids and axillary arteries can be performed in the same session, which increases sensitivity. Positive evidence of vasculitis on Doppler sonography is usually based on evidence of a hypoechogenic thickened vessel wall, in contrast to the focal hyperechogenic changes seen in atherosclerosis (Fig. 1A, B). New technical developments in PET, CT, and MRI equipment now allow imaging of the temporal arteries, which may be an additional diagnostic tool.

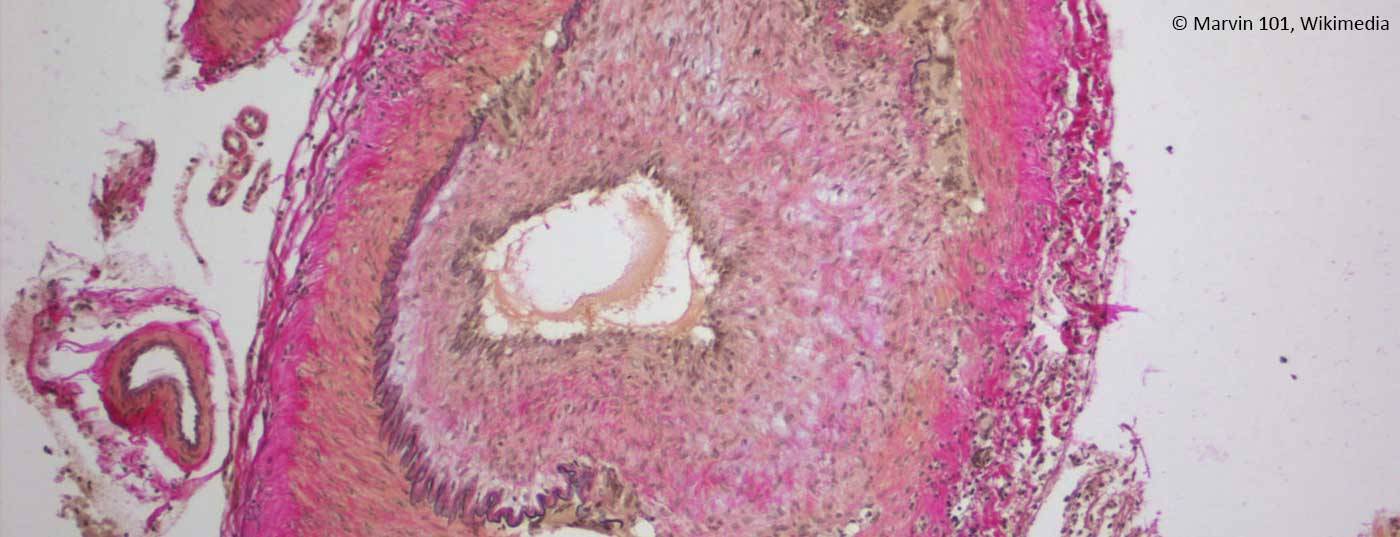

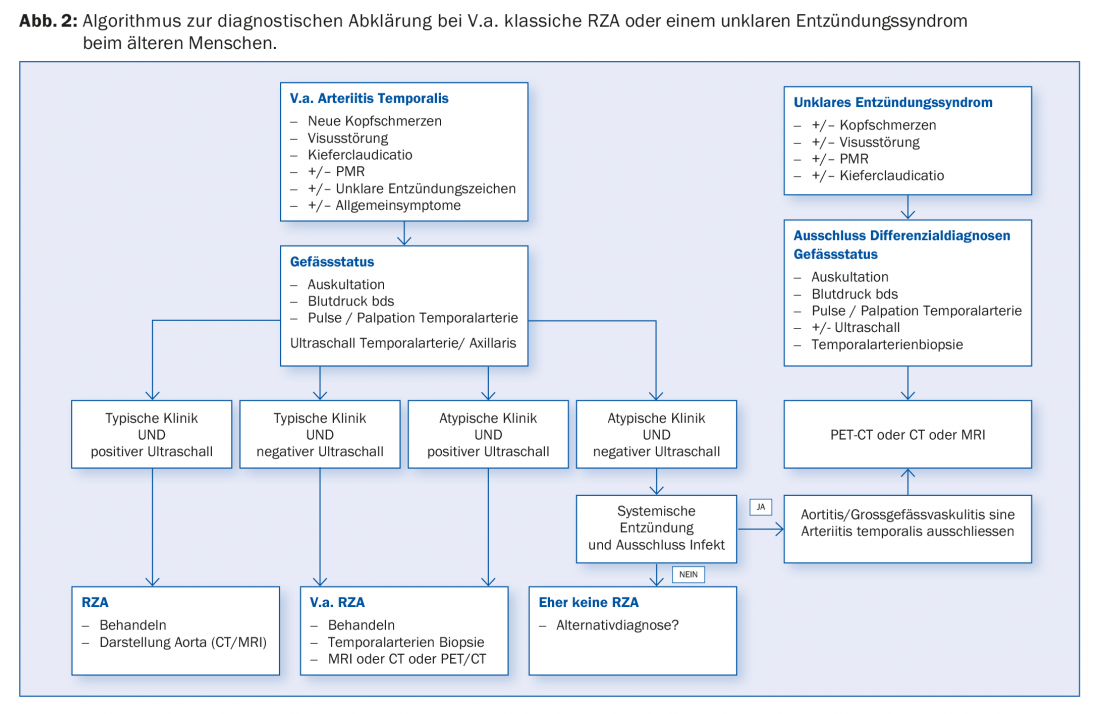

Positive confirmation of diagnosis: Positive confirmation of diagnosis by histology provides evidence of the presence of RZA. This shows an infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages, which migrate through the entire vessel wall (Fig. 1C). Pathognomonic is the detection of giant cells; fused, multinucleated macrophages (Fig. 1D). However, these are absent in up to half of the patients. Other signs may include a thickened intima with narrowing of the vascular lumen, fragmentation of the lamina elastica interna, or inflammation in the adventitia. However, the latter findings are suggestive of RZA only in the presence of concomitant evidence of an inflammatory infiltrate. If they occur without inflammation, they may also be age-related degenerative. Further, it should be noted that after 7 – 14 days of treatment with prednisone, the inflammatory infiltrate disappears, resulting in a “false negative” biopsy. Mind you, a negative biopsy in a typical clinic never excludes the diagnosis, as up to 40% of patients may have a negative biopsy. Because it remains an invasive procedure (albeit minor), efforts are underway to establish other diagnostic algorithms that eliminate the need for biopsy in certain clinical scenarios (Fig. 2).

Oligosymptomatic RZA – an important differential diagnosis.

Increasingly, the diagnosis of RZA is made in patients with systemic inflammation in the foreground – often only after lengthy investigations. The diagnosis in these patients is then often based on imaging. Imaging performed to search for tumor/infection or even intentionally to search for RZA then reveals corresponding changes in the aorta and its branches that suggest the diagnosis (Fig. 2).

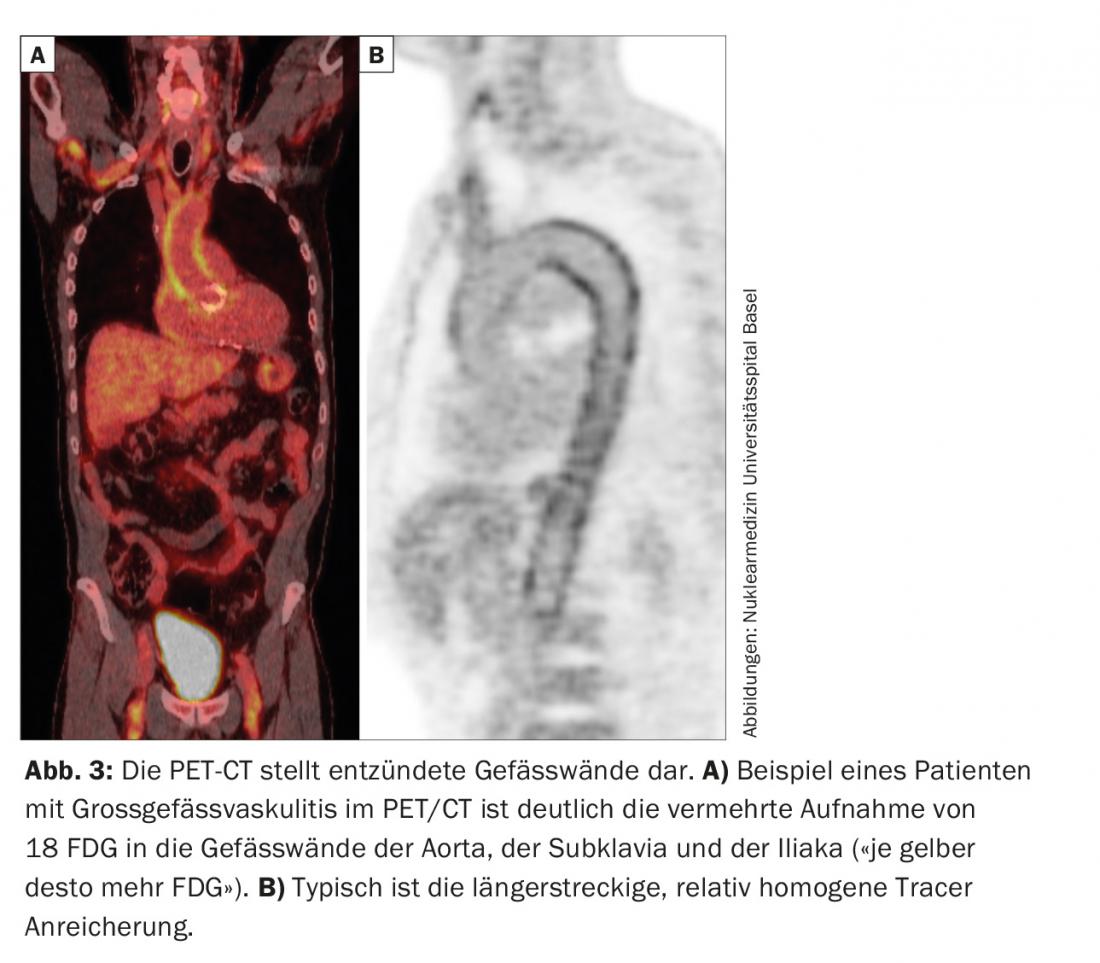

RZA should be thought of in elderly patients, with systemic inflammation and lack of obvious signs of infection or malignancy [2]. Even if they do not complain of headache, loss of visual acuity or chewing pain (see case study 2). A temporal artery biopsy can also be performed in this case. In the positive case the diagnosis is confirmed, in the negative case it is not excluded, because in the absence of “head symptoms” the temporal arteries may not necessarily be inflamed. This is why it is also referred to as large vessel vasculitis. Various imaging modalities (MRI, PET, CT) are capable of visualizing vascular wall inflammation. These may present as wall thickening (ultrasound), with contrast imaging on CT, for example. PET depicts – via a nuclear medicine tracer – the uptake of glucose into tissue. Inflammation requires more glucose, which is why an inflamed vessel wall lights up on PET (Fig. 3) . Since imaging is based on metabolic activity, the PET examination is probably close to a true activity determination. This is in contrast to CT, MRI, and ultrasound, where chronic, postinflammatory changes are sometimes difficult to distinguish from active inflammation.

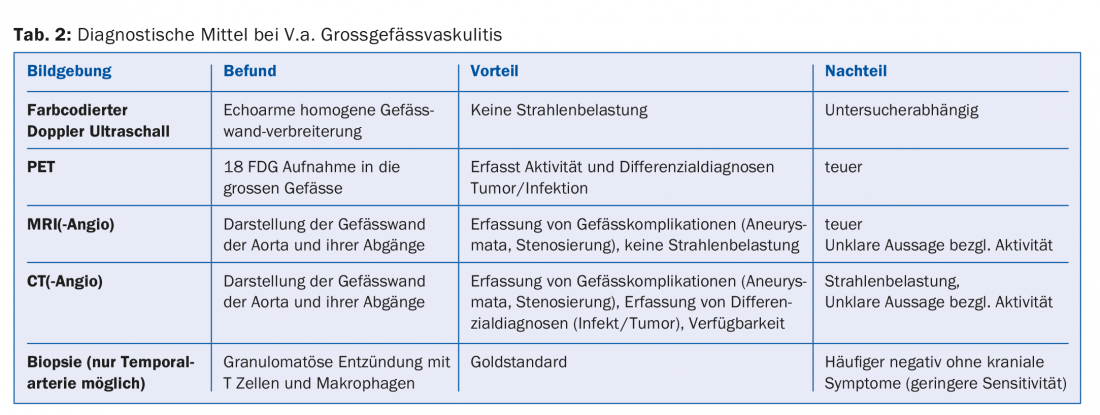

One advantage of imaging the large vessels is the simultaneous visualization of any pre-existing vascular complications such as stenoses or aneurysms. Since RZA is associated with a significantly increased risk of such vascular complications, initial imaging of the great vessels is generally recommended in every RZA patient (Tab. 2). Again, therapy is essential because these patients may well develop ischemic or aneurysmal/stenotic complications during the course of the disease. A suggested set of diagnostic work-up steps for V.a. giant cell arteritis is shown in Figure 2.

High-dose prolonged prednisone treatment.

Steroids are still the basis of therapy. The usual dose used is 1 mg/kg bw, with a maximum of 60 mg/day recommended [1]. Exceptions are severe ischemic events. These include visual disturbances/blindness or vasculitic stroke. Here, higher doses are initially used in the form of shock therapy to prevent further ischemia.

The steroid dose should be reduced over time with the goal of being at 5 mg after about 6 months [1]. During this phase, the clinic as well as the inflammatory parameters should be checked regularly. If there is evidence of recurrence, the dose must be adjusted accordingly. More than half of patients experience one or more relapses [3]. Therefore, steroid maintenance therapy is usually added as a preventive measure. There are few data regarding the best duration and dose of this therapy. In particular, to date there are no predictive factors that allow identification of patients who are at higher risk of relapse. Usually, therapy is with 5(-7.5) mg prednisone for another year to a maximum of 18 months [1,4].

The downside of disease control is steroid side effects. These are extremely common due to age and comorbidities, so nearly every patient develops at least one problem. Among them, cataract, fractures and infections were the most frequent (31%). Furthermore, hypertension (22%) or diabetes mellitus (9%) often occurs [5].

In addition to immunosuppressive treatment and control of side effects, several other prophylactic measures are recommended [1]. Presumably, patients have fewer ischemic events with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), which is why the EULAR recommends low-dose (75-150 mg/day) ASA therapy. When ASA and cortisone are combined, a proton pump inhibitor should be prescribed. Furthermore, all patients should receive osteoporosis prophylaxis and, if necessary, therapy. Accordingly, we routinely perform risk assessment and bone densitometry at the start of therapy.

Therapy-refractory course and recurrence treatment

One recurrence is often followed by a second. Repeated cortisone increases then lead to high cumulative doses, which can potentiate side effects and compromise the immune system in the long term.

In a meta-analysis of randomized trials, only metotrexate has so far been shown to be a weakly steroid-sparing drug. In recent years, tocilizumab (anti-IL6 receptor antagonist Actemra®) has become established as an alternative therapy. Here, amazing and rapid improvements have occurred in refractory patients [6]. Because IL-6 is also the major stimulus for acute phase protein production in the liver, IL-6 blockade results in rapid normalization of CRP and ESR.

Does IL6 blockade herald a new era?

New data are available on the use of tocilizumab in primary therapy. In a randomized controlled trial at the University Hospital of Bern, it was shown that patients who primarily received tocilizumab had hardly any recurrences despite a relatively rapid reduction of prednisone therapy, with a clear steroid-sparing effect [7]. Data from an international pivotal trial of initial treatment with tocilizumab (GiACTA) reached the same conclusion, with definitive data not expected until late 2016. It is anticipated that this will lead to more frequent and earlier use of tocilizumab in patients with RZA.

It should be noted that CRP is suppressed under tocilizumab and thus infections can be masked. Thus, in these patients, early evaluation and treatment is essential in the presence of V.a. infection. Other side effects include transaminase and lipid elevations, as well as the rare but potentially dangerous neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Bowel perforations were seen more frequently in patients with diverticulitis in the initial pivotal studies.

Literature:

- Mukhtyar C, et al: EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68(3): 318-23.

- Muto G, et al: Large vessel vasculitis in elderly patients: early diagnosis and steroid-response evaluation with FDG-PET/CT and contrast-enhanced CT. Rheumatology International. 2014; 34(11):1545-54.

- Alba MA, et al: Relapses in patients with giant cell arteritis: prevalence, characteristics, and associated clinical findings in a longitudinally followed cohort of 106 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014; 93(5): 194-201.

- Weyand CM, et al: Clinical practice. Giant-cell arteritiis and polymyalgia rheumatica. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(1): 50-7.

- Proven A, et al: Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 49(5): 703-8.

- Osman M, et al: The role of biological agents in the management of large vessel vasculitis (LVV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9(12):e115026.

- Villiger PM, et al: Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387(10031): 1921-7.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(9): 22-26