This article provides an overview of the various forms of bullous autoimmune dermatoses and a summary of current therapeutic recommendations and treatment options.

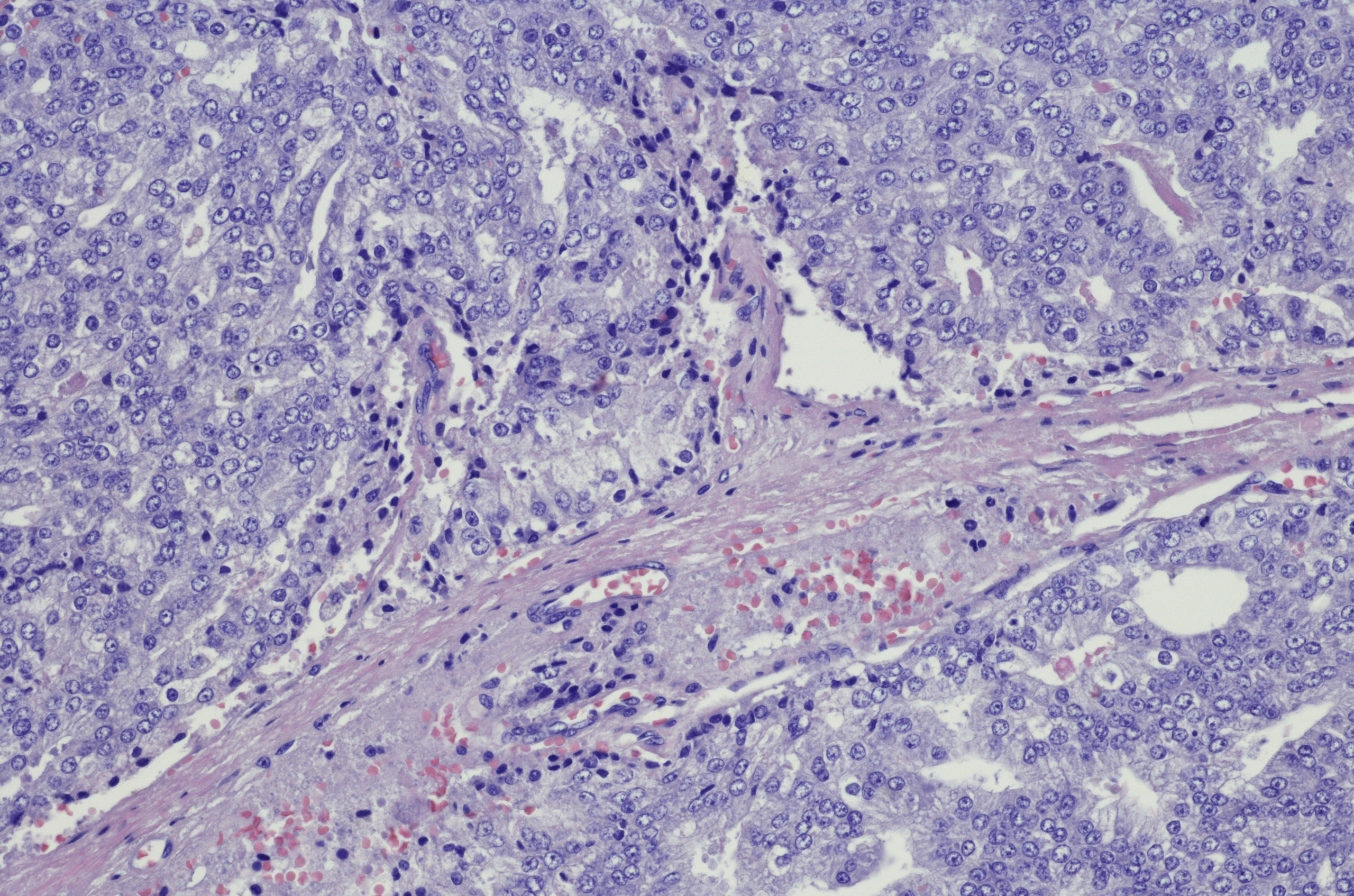

Blistering autoimmune diseases are usually severe diseases of the skin – and often of the mucous membranes as well. They are characterized by the presence of IgG or IgA autoantibodies against structural proteins of the skin. These structural proteins are of great importance for the cell adhesion of keratinocytes (pemphigus diseases) or for the adhesion of the epidermis with the dermis (pemphigoid diseases, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, dermatitis herpetiformis).

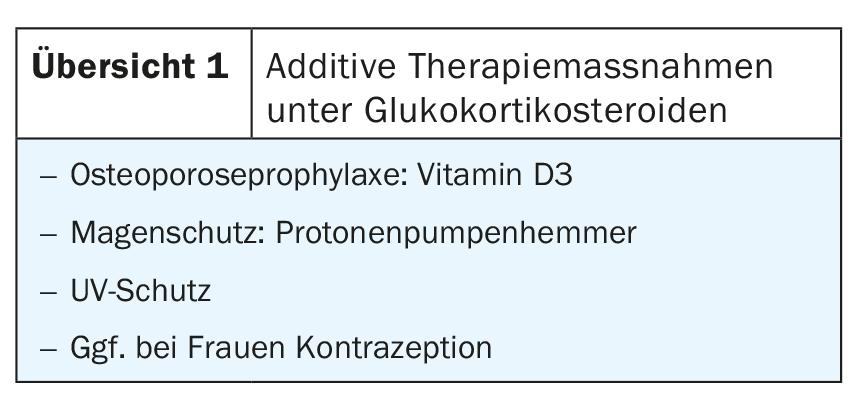

Thus, blistering occurs intraepidermally in the pemphigus diseases and subepidermally in the other bullous autoimmune diseases. The great clinical heterogeneity and the different courses also represent a therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Local and oral glucocorticosteroids are the first-line agents with the exception of dermatitis herpetiformis. Additive therapy measures are required under systemic therapy with corticosteroids (overview 1). In order to save corticosteroids, these are combined with further immunosuppressants in the course.

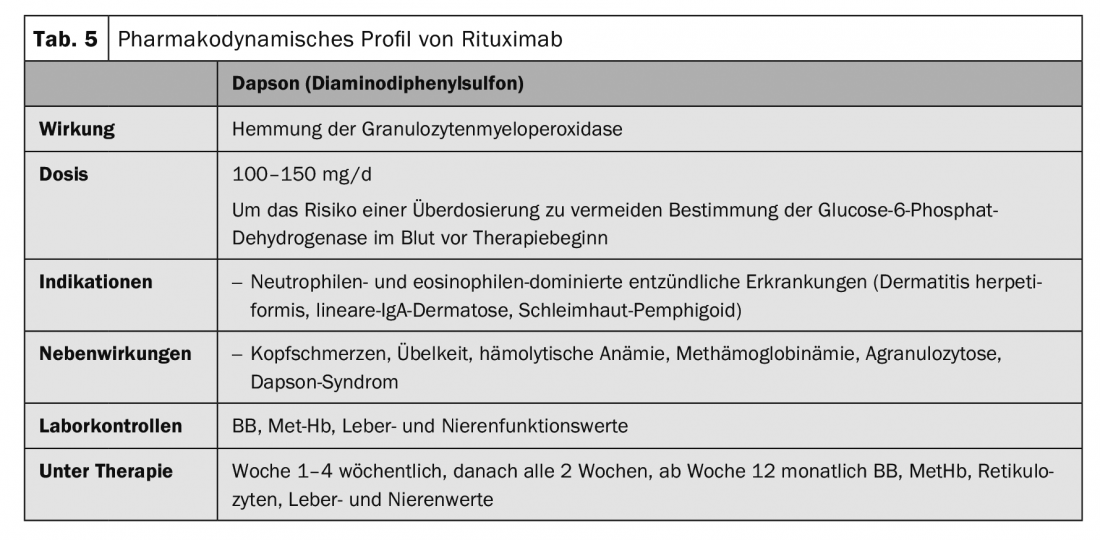

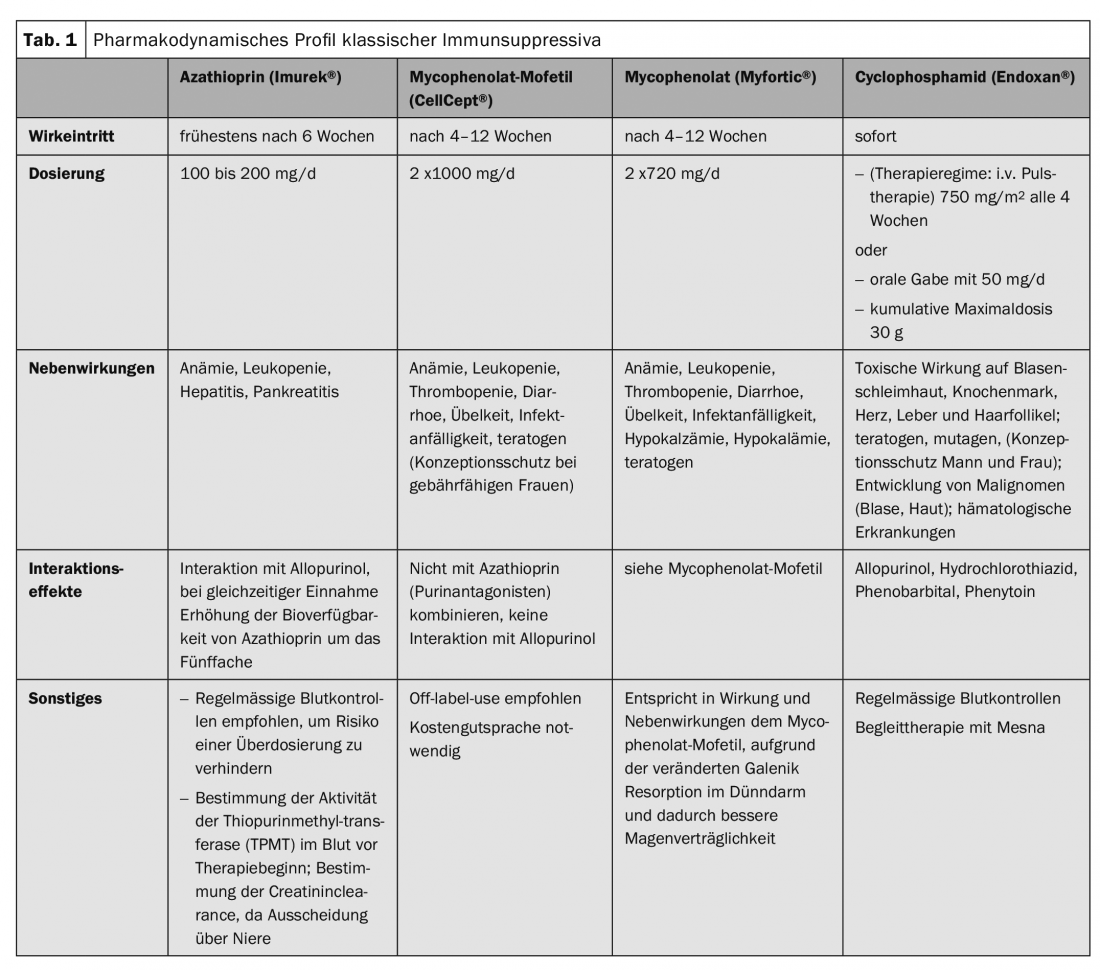

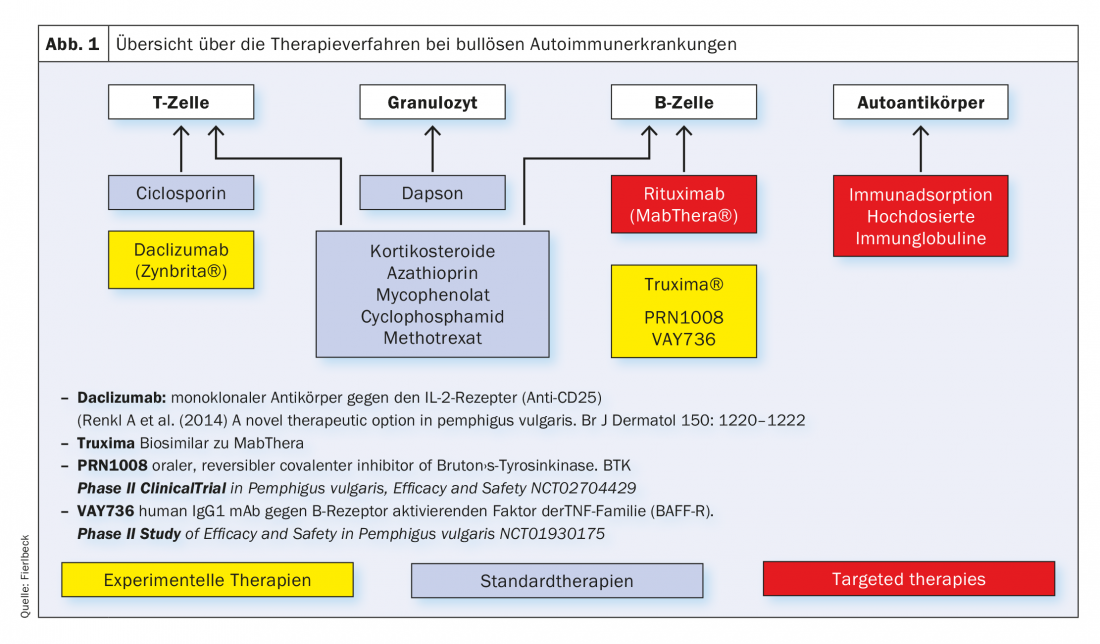

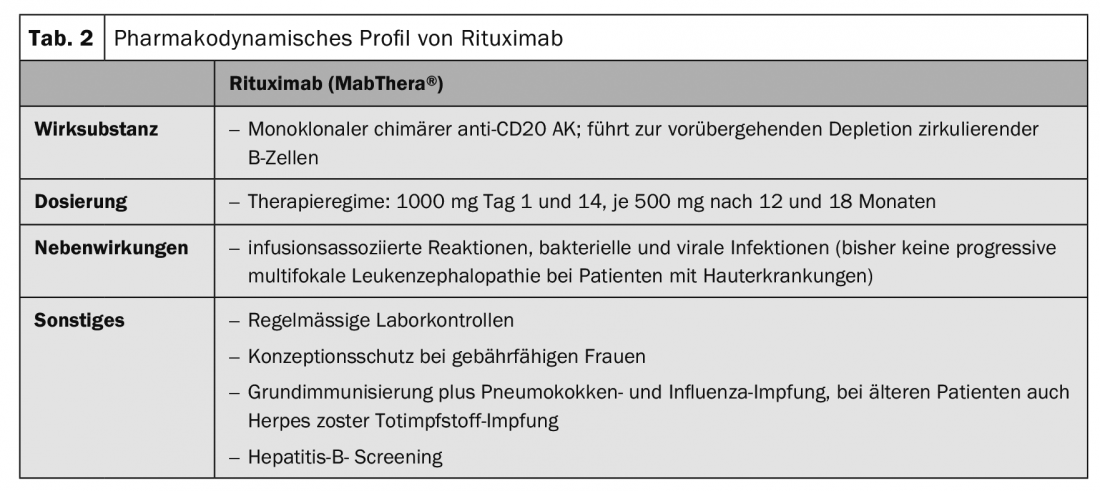

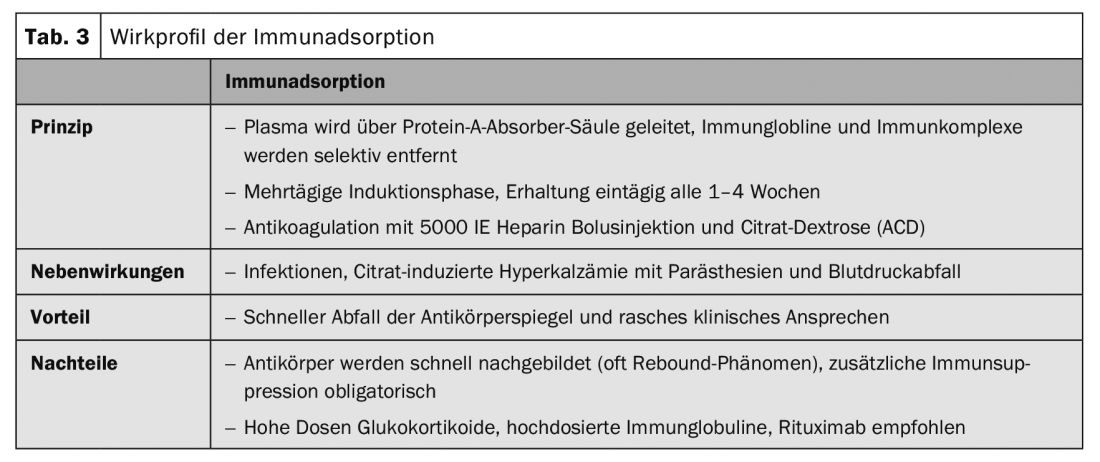

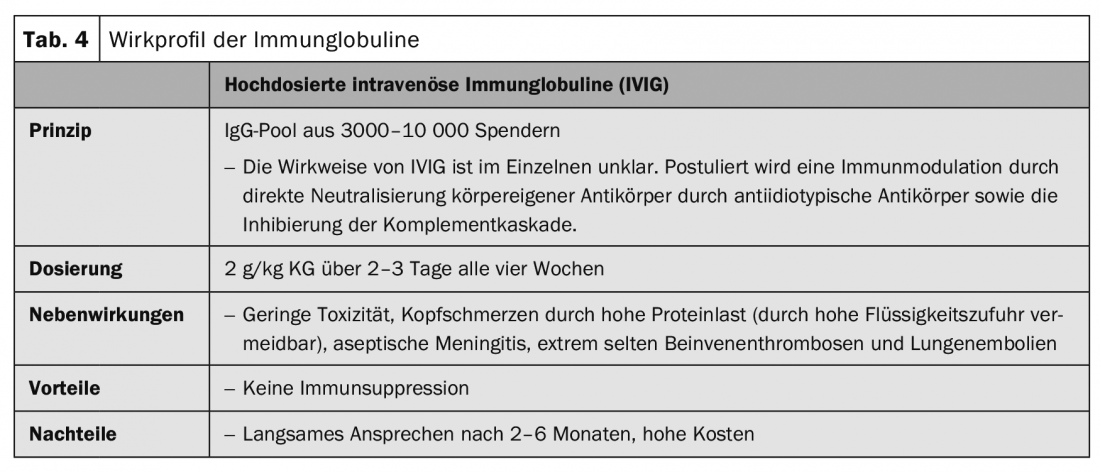

In recent years, the classical immunosuppressive drugs have been (Tab. 1), which influence the metabolic processes of T and B cells at the cellular level, supplemented by targeted therapies. (Fig.1). Essentially, these are rituximab (Tab.2), Immunoadsorption method (Tab. 3) and the use of high-dose immunoglobulins. (Tab.4). Rituximab is a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody for depletion of peripheral B cells that form autoantibodies (Tab.2).

Immunoadsorption procedures selectively remove autoantibodies and immune complexes from plasma via high-affinity absorbers (Table 3).

Intravenous high-dose immunoglobulins are designed to neutralize inflammatory mediators and autoantibodies (Table 4).

There is an increased risk of reactivation of latent infections during therapy with immunosuppressants, so that infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, tuberculosis, and chronic bacterial infections must be ruled out before initiating therapy. Opportunistic candida infections and herpes infections (herpes simplex, varicella zoster) may occur during therapy. An increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders and skin tumors has been described during long-term therapy with immunosuppressants. Because of increased photocarcinogenesis, UV protection and regular skin inspections are required. Before initiating immunosuppressive therapy, check the patient’s vaccination status. Vaccination with live vaccines during immunosuppressive therapy is contraindicated, and vaccination with attenuated vaccines may have reduced success. In patients over 50 years of age, shingles vaccination with the herpes zoster subunit vaccine is indicated [1].

Pemphigus diseases

Pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and paraneoplastic pemphigus are subsumed under this umbrella term. Systemic glucocorticosteroids are the focus of therapy. Depending on the severity of the disease, initial doses correspond to 1-2 mg/kg prednisolone equivalent per day. Consolidation therapy is based on disease activity. If no new blisters occur over 8 days, the steroid dose is reduced by 25% every 2-4 weeks. From 30 mg prednisolone equivalent per day, further reduction is even slower. The goal is to reach the Cushing threshold (7.5 mg prednisolone). In order to save glucocorticosteroids, these are combined with other immunosuppressants (tab. 1) . The dose of the immunosuppressive agent remains unchanged over the entire duration of therapy, provided that no side effects occur.

The most common adjuvant immunosuppressant is azathioprine at a dosage of 100-150 mg/d. In case of decreased enzyme activity of thiopurine methyltransferase or concomitant administration of allopurinol, the dose must be reduced. Blood samples are required before and during therapy (Table 1).

If side effects occur with azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or, for gastrointestinal side effects, mycophenolic acid are used. Both drugs have a steroid-sparing effect and lead to faster remission (Table 1).

In very refractory courses, cyclophosphamide may be combined with corticosteroids. Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating, i.e., DNA-crosslinking, agent with irreversible effects on ovarian reserve and spermatogenesis and is therefore obsolete in younger patients. In addition, a number of toxic side effects and development of malignancies may occur (Tab. 1). The approval in the EU was therefore restricted in 2012 to life-threatening autoimmune diseases.

Prospective, multicenter, randomized clinical trials with and without corticosteroids have demonstrated the efficacy of rituximab (Table 2) with remissions of up to 80% at 24 months. Autoantibody titers (anti-desmoglein I and III) slowly decreased during the first weeks after infusion and reached the lowest levels after approximately 180 days. A clinical response was observed after 2-3 months. Based on the studies, rituximab was approved for initial therapy of severe and moderate pemphigus in the United States in June 2018 [2,3]. Approval in Europe is expected in the next few years.

Initial study results on immunoadsorption (IA) (Table 3) in pemphigus were published in 2007 [4]. In the meantime, more than 100 patients with different treatment protocols have been published. All case series showed, in contrast to rituximab, a rapid decrease of autoantibodies and a rapid clinical improvement but also a high relapse rate after a short time. The combination of IA with rituximab resulted in rapid and long-lasting remissions [5].

Case series and individual case reports have reported good response after several therapy series of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) (Table 4) in combination with glucocorticosteroids for pemphigus vulgaris and paraneoplastic pemphigus as second- or third-line therapy after failure of combined immunosuppressive therapy. Only after several months of therapy did a response become apparent.

Bullous pemphigoid

Therapy of bullous pemphigoid must be adapted to the disease activity and comorbidities of each individual patient. Generally, milder therapeutic procedures are used than for pemphigus disease. In localized and moderate bullous pemphigoid, disinfectant and topical anti-inflammatory treatments with clobetasol propionate twice daily are often sufficient. However, topical, large-area treatment twice a day, is often impractical in elderly patients. Systemic treatment is usually necessary. Systemic therapy with initial 0.5 mg/kg/d prednisolone equivalent in combination with adjuvant immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil, to save glucocorticoids, is the first choice therapy in addition to topical treatment (Tab. 1). Other adjuvant therapies described include methotrexate (15 mg/week), dapsone (100 mg/d, Tab. 5), and tetracycline (200 mg/d). Immunoadsorption (Table 3) was used to demonstrate the rapid decrease in autoantibody levels of bullous pemphigoid in serum and an associated therapeutic effect in a case series of 20 patients [6].

Mucous membrane pemphigoid

This autoimmune dermatosis is also known as scarring pemphigoid. The disease is characterized by great clinical heterogeneity with and without scarring. All mucous membranes with squamous epithelium (oral mucosa, conjunctiva, nasopharynx, esophagus, vulva, and rectum) may be affected. The therapy depends on the clinical manifestation; above all, scarring must be prevented (Fig. 2). In addition to high-dose glucocorticoids in combination with adjuvant immunosuppressants, therapy with cyclophosphamide (Tab. 1), IVIG (Tab. 4) or rituximab (Tab. 2 ) may also be recommended in refractory patients [7].

Linear IgA dermatosis

The first-line agents for linear IgA dermatoses are glucocorticosteroids and dapsone (Table 5). Glucocorticosteroids are the far less effective agents in this disease than in pemphigus or bullous pemphigoid. Immunadsorption (Table 3), IVIG (Table 4), and rituximab (Table 2) [8,9] have been described as effective in case reports.

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita shows marked resistance to therapy in many cases. The mechanobullous form in particular is often refractory to treatment with glucocorticosteroids in combination with adjuvant immunosuppressants such as azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil (Tab.1). In a case series with 3 patients and in individual case reports, it was shown that Rituximab (Tab. 2) as monotherapy leads to long-lasting remissions in more than half of patients and in combination with IVIG (Tab. 4) or immunoadsorption (Tab. 3) in more than 75% of patients [10].

Dermatitis herpetiformis Duhring

In addition to the skin disease, a gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease) is always present at the same time, although more than 80% of patients do not show gastrointestinal symptoms, but usually have subclinical villous atrophy or inflammation in the jejunum. The therapy is based on a lifelong gluten-free diet. A gluten-free diet also prevents the occurrence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and probably carcinoma of the digestive tract. The effect of the gluten-free diet only appears on the skin after several months, so that dapsone (Tab. 5) should always be used initially. The underlying enteropathy is not affected by dapsone. In case of dapsone intolerance, sulfasalazine or colchicine may be given.

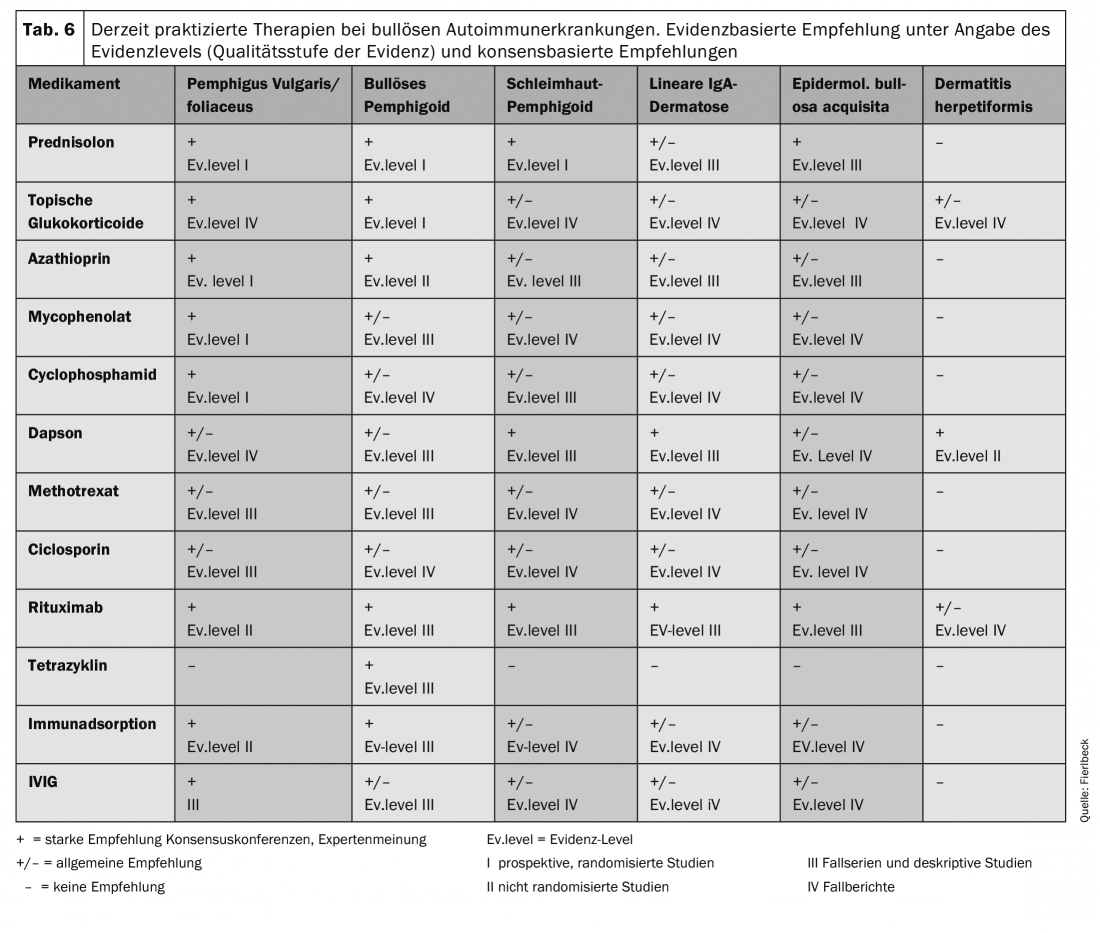

Summary

An overview of the currently practiced therapies is given in Table 6. The therapy recommendations are based on clinical studies (evidence level) and general recommendations (consensus conferences, expert opinions).

Take-Home Messages

- Local and oral glucocorticosteroids in combination with azathioprine are first-line agents except for dermatitis herpetiformis.

- In bullous pemphigoid, a trial of potent topical glucocorticosteroids can be made. However, oral therapy with low doses of glucorticosteroids in combination with azathioprine, is usually required.

- Rituximab is indicated for severe, refractory autoimmune bullous dermatoses. Because of the delayed effect of rituximab, glucocorticosteroids should be combined initially.

- Immunoadsorption leads to clinical improvement within a few days; additional immunosuppression is required because of the rapid rebound of autoantibodies and clinical deterioration.

- In dermatitis herpetiformis, a lifelong gluten-free diet is required, even in the absence of manifest enteropathy. Dapsone is the drug of first choice. The effect of the gluten-free diet sets in only after months, dapsone works within a few days.

Literature:

- STIKO: Communication of the Standing Commission on Vaccination (STIKO) at the RKI. Scientific rationale for recommending vaccination with the herpes zoster subunit total vaccine. Robert Koch Institute (RKI), Epidemiological Bulletin 50, Dec. 13, 2018. www.rki.de

- Jolly P, et al: First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisolone alone for the treatment of pemphigus. Lancet 2017; 389(10083): 2031-2040. dx.doi.org/10.1016/SO140-6736(17)30070-3.

- Murrell DF, et al: Diagnosis and management of pemphigus: recommondation by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018 Feb 10. pii: S0190-9622(18)30207-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.021. [Epub ahead of print]

- Zillikens D, et al: Recommendation for the use of immunopheresis in the treatment of autoimmune bullous disease. JDDG 2007; 5(10): 366-373.

- Behzad M, et al: Combined treatment with immunoadsorption and rituximab leads to fast and prolonged clinical remission in pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166(4): 844-852.

- Hübner F, et al: Adjuvant treatment of severe/refractory bullous pemphigoid with protein A immunoadsorption. JDDG 2008; 16(9): 1109-1119.

- Le-Roux-Viller C, et al: Rituximab for patients with refractory mucous membrane pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(7): 843-849.

- Enk A, et al: Use of high-dose immunoglobulins in dermatology. JDDG 2009; 7(9): 806-812.

- Pinard C, et al: Linear IgA bullous dermatosis treted with rituximab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019; 5(2): 124-126. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.11.004

- Bevans SL, Sami N: The Use of Rituximab in treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: Three new cases and a review of the literature. Dermatol Ther 2018; 31(6):e12726. doi: 10.1111/dth12726 [Epub 2018 Oct 3]

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(2): 21-27