Many asthmatics, especially those with severe disease, report mobility problems and limitations in daily activities that severely affect their quality of life. Among the contributing factors, low muscle mass and strength may be important. Dutch researchers now investigated the relationship between muscle mass and strength and functional or clinical outcomes in patients with moderate to severe asthma.

There are limited data on muscle mass and strength in asthma, although some studies suggest that muscle dysfunction may play a role. Previous studies have shown that patients with severe asthma have lower muscle mass than patients with mild to moderate asthma, although they were more likely to be overweight. In fact, fat-free mass – a surrogate marker for muscle mass – in these patients with severe asthma was comparable to that of patients with stage IV COPD, write Edith Visser of the Department of Epidemiology at Medical Centre Leeuwarden and colleagues. They therefore targeted levels of muscle mass and strength in patients with varying asthma severity and investigated whether muscle mass and strength were associated with functional and clinical asthma outcomes. Furthermore, they wanted to determine if systemic inflammatory markers were associated with low muscle mass and strength.

The study [1] included 114 patients with moderate (GINA stage 3, 16%), moderate-to-severe (GINA 4, 30%), and severe (GINA 5, 54%) asthma (36% male; mean age, 51.9 years; body mass index, 27.7 ± 5.7 kg/m2). Muscle mass and strength were determined by fat-free mass index (FFMI), creatinine excretion rate (CER) in a 24-hour urine sample, and hand strength test (HGS). Functional outcomes were determined by pulmonary function tests and 6-minute walk distance, while clinical outcomes were determined by asthma control, quality of life, and health care utilization questionnaires. The associations between muscle mass and strength and asthma outcomes were examined with multivariable regression analyses.

Level of muscle mass and strength

Mean FFMI, CER, and HGS for men were 20.1 ± 2.4 kg/m2, 15.3 ± 6.0 mmol/d, and 48.8 ± 9.6 kg, respectively. Measures of muscle mass and strength were lower, as expected, in women who had an FFMI of 17.3 ± 2.0 kg/m2, a CER of 10.8 ± 2.7 mmol/d, and an HGS of 29.3 ± 7.2 kg. According to the predefined criteria for low muscle mass and strength, 18 patients (16%) had low FFMI, 9 patients (8%) had low CER, and 6 patients (5%) had low HGS. These values for muscle mass and strength were independent of GINA classification.

Lower muscle mass associated with greater obstruction

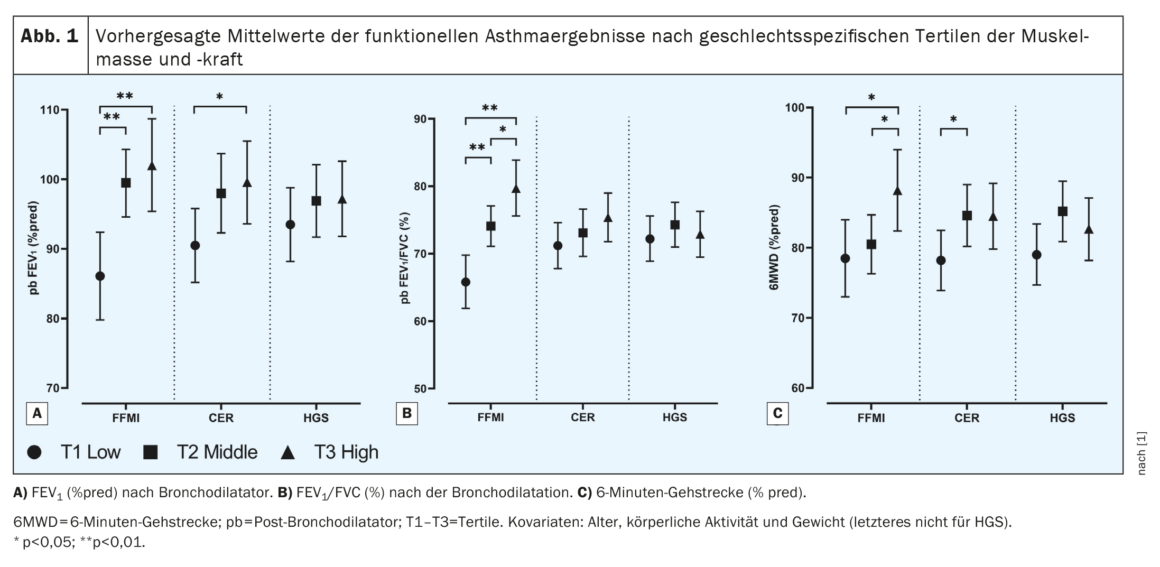

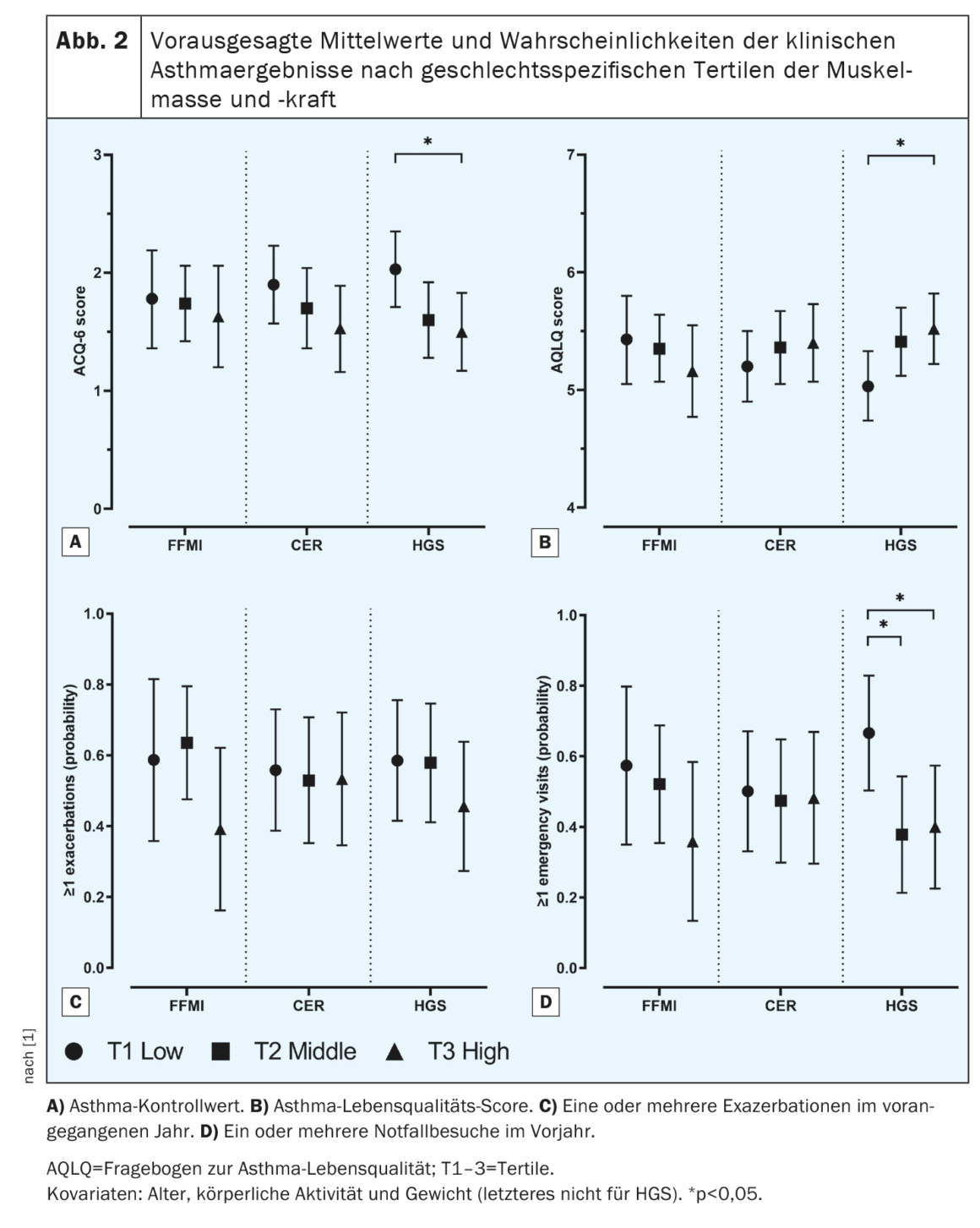

When considering functional asthma parameters, the authors found that patients in the lowest tertile (T1) of FFMI had statistically significant lower values for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC after bronchodilation, as well as poorer functional physical performance as measured by 6MWD, than patients in the highest tertile (T3). (Fig. 1). A similar relationship with these functional parameters was shown for the tertiles of CER, although only for FEV1 and 6MWD significantly. Muscle strength was not related to any of the functional outcomes. With regard to clinical asthma outcomes, no significant associations were found between FFMI or CER and asthma control, asthma-related quality of life, emergency visits, or exacerbations (Fig. 2). However, there was an association with muscle strength, with patients in the lowest tertile of HGS having poorer asthma control, poorer quality of life, and a higher likelihood of one or more emergency visits than patients in the highest HGS tertile.

Regarding associations between systemic inflammatory markers and muscle mass and strength, higher leukocyte levels were significantly associated with lower FFMI (regression coefficient β -0.13; 95% CI -0.26 to -0.01) after adjusting for sex, age, physical activity, and weight. None of the other inflammatory markers were associated with FFMI. In addition, higher blood eosinophil levels (β -3.11; 95% CI -7.46 to 1.25), higher IL-6 levels (β -0.29; 95% CI -0.70 to 0.13), and lower albumin levels (β 0.24; 95% CI -0.07 to 0.56) were associated with lower CER, although not statistically significantly. Finally, higher leukocyte levels (β -0.62; 95% CI -1.42 to 0.19), lower fractional exhaled nitric oxide levels (β 0.05; 95% CI -0.01 to 0.10), and lower C-reactive protein levels (β 0.21; 95% CI -0.05 to 0.47) also showed an association with lower muscle strength, although again not statistically significant.

The results would show that 8% to 16% of patients had low muscle mass, depending on the parameter used, and this was independent of asthma severity as expressed by GINA class, the researchers write. “However, lower muscle mass was associated with greater airway obstruction and lower functional exercise capacity, while lower muscle strength was associated with poorer asthma control and quality of life and a higher likelihood of emergency department visits.” They suggest that the physical inactivity that often accompanies uncontrolled asthma leads to a loss of muscle mass over time. Also, daily OCS use appears to be an independent predictor of low FFMI, either as a result of a direct negative effect of OCS on muscle metabolism or as a possible manifestation of the underlying asthma type. Higher eosinophil counts were also possibly related to lower muscle mass, although not ignificantly, which could be attributed in part to the anti-inflammatory effects of the biologics or OCS.

If further longitudinal studies confirm that changes in muscle mass and strength affect clinical outcomes, muscle function could become a target for asthma treatment, the Dutch group concluded. Improving muscle mass and strength, they hypothesized, could potentially lead to improved asthma outcomes, as has been shown for exercise training in COPD.

Literature:

- Visser E, de Jong K, van Zutphen T, et al: Muscle Function in Moderate to Severe Asthma: Association With Clinical Outcomes and Inflammatory Markers. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023; doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.12.043.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2023; 5(1): 20-22.