The term non-alcoholic fatty liver disease encompasses a spectrum of findings ranging from simple steatosis or fatty liver to steatohepatitis as an inflammatory form to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. There is a close association with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. However, the pathophysiology is not conclusively understood, which is why drug treatment is not generally recommended.

Elevated liver values as part of preventive health care are not uncommon, explains Prof. Dr. Thomas Berg, Head of the Hepatology Section and Acting Director of the Clinic for Gastroenterology at Leipzig University Hospital (UKL) [1]. More than 70% of patients have fatty liver disease, and the cause of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may be metabolic disorders, hereditary diseases, diabetes, or medications in addition to obesity [2].

NAFLD is characterized by excessive hepatic fat accumulation. Histologically, more than 5% of hepatocytes show steatosis. A distinction is made between steatosis alone, i.e., nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is referred to when additional inflammatory changes occur in the liver. NASH represents the progressive form of NAFLD with an increased risk of developing fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3]. Usually, patients with NAFL have hyperlipidemia or metabolic syndrome in addition to unhealthy lifestyle, and there is a higher cardiovascular risk. Patients with NASH usually already have advanced fibrosis.

Fibrosis-4 Index for liver fibrosis

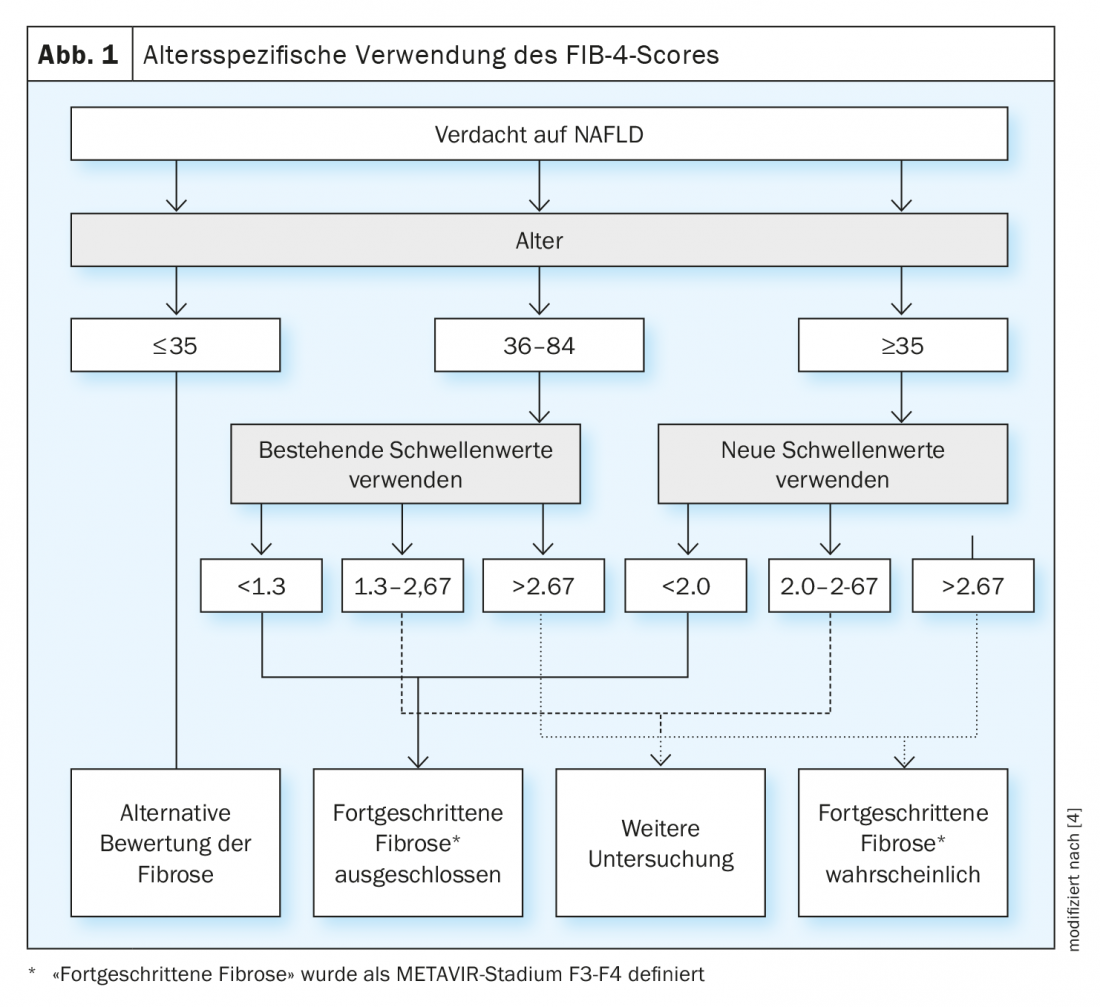

A practical approach to risk stratification in suspected NALFD is the so-called fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4). This allows non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis. The FIB4 score is calculated according to the following formula: [Alter × Aspartataminotransferase (AST)] / [Thrombozyten × Alanin-Aminotransferase (ALT)]; with a FIB4 score ≤1.30 (<2.0 in patients 65 years and older), there is a lower risk of liver fibrosis, values >3.25 indicate fibrosis with strong probability, values in between should be controlled accordingly (e.g. with transient elastography) (Fig. 1) [4].

Imaging techniques

Early signs of liver cirrhosis are found on B-scan ultrasonography from inhomogeneous texture of liver tissue, irregular liver surface, or enlargement of the lobus caudatus, among others. Sign of advanced chronic liver disease with transition to cirrhosis is thrombocytopenia. In addition, limitations in liver synthesis function and hepatic detoxification are noticeable. Diagnostic equipment includes upper abdominal sonography and gastroscopy. Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) is used to detect esophageal varices and assess their bleeding risk and should be ordered as part of the initial diagnosis of liver cirrhosis or suspected cirrhosis. Performing a liver biopsy is contraindicated if the diagnosis of cirrhosis can be clearly established clinically and with imaging. Liver biopsy, on the other hand, is indicated in cases of unclear etiology and when the stage of liver disease cannot be clearly identified on the basis of the parameters already mentioned.

Lifestyle adjustment

A causal drug treatment for NAFLD is still not available. Currently, the best possible therapy is lifestyle modification and increased physical activity, with the goal of weight loss of 0.5 to 1 kg/week. Weight reduction should be at least 7% to 10% of body weight, since reductions of 7% or more have been shown to improve all histologic components of NASH (Fig. 2) [5]. In obese patients, a weight reduction of 10% within one year is already sufficient to significantly reduce NASH score and fibrosis stage. However, even under strictly controlled study conditions, only about 10% of patients achieve the recommended 10% weight loss in one year. Drugs for the treatment of metabolic syndrome, such as statins and antidiabetics, also play a not insignificant role. The possible positive influence of vitamin E, ursodeoxycholic acid and caffeine is still controversial.

Literature:

- Prof. Dr. Thomas Berg: Gastroenterology II. Hepatitis, fatty liver hepatitis, rare liver diseases, biliary diseases, fresh up family medicine 11.02.2022.

- Brown GT, Kleiner DE: Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Metabolism 2016; doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.11.008.

- EASEL, EASD & EASO: Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatology 2016; doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004.

- McPherson S, et al: Age as a Confounding Factor for the Accurate Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Advanced NAFLD Fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.453.

- Romero-Gómez M, et al: Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatology 2017; doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.016.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(5): 34-35