Prof. Dr. med. Jürg Kesselring, Valens Clinics, spoke on the topic of “Parkinson’s Syndrome” at the Update Refresher Internal Medicine. After a brief historical review of the origins and research of this clinical picture, he discussed motor and non-motor symptomatology, going into more detail about the problem of orthostatic hypotension.

Prof. Dr. med. Jürg Kesselring from the Valens Clinics first gave a brief overview of the history of Parkinson’s syndrome: it was first described in 1817 by its namesake James Parkinson, who called the condition “shaking palsy”. It is accompanied by involuntary tremor and reduced muscle strength (even with inactivity and support). In addition, there is the tendency to bend the trunk forward and switch from walking to running. The disease does not affect the intellect and the senses.

Then, in the 19th century, the term akinesia was introduced. This was followed in the late 1960s by the development and approval of levodopa. A little over a decade later, the first dopamine agonists appeared and, in the late 1980s, the MAO inhibitor selegiline.

Later, other dopamine agonists came on the market. The definition of Parkinson’s disease has been further specified over time: Bradykinesia, hypokinesia, and akinesia include difficulty starting, slowing, and reduction in range of motion, loss of voluntary and of automatic movements. Rigor is characterized, among other things, by tension in the extremities and back and velocity-independent increases in tone. In addition, resting tremor, asymmetric hand tremor, postural abnormalities (simian posture, postural instability, impaired reflexes), and gait disturbances occur.

“A very crucial but often neglected part of the disease is central dysautonomia,” the speaker said. Autonomic dysregulation, e.g., with hypersalivation, seborrhea, orthostatic hypotension, micturition and erectile dysfunction is one of the non-motor symptoms of PD. In addition, cognitive deficits (e.g., bradyphrenia) occur in 5-20% and depression in approximately 40%. Sleep and sensory disturbances, such as anosmia, pain, and paresthesias, can also place a heavy burden on the patient.

Epidemiology, development, diagnostics

“After 60 years of age, the incidence increases (0.2-0.5%), but in 15% of cases the disease begins before 45 years of age. The prevalence is 200-300/100,000 population. It affects about 1% of those over 60 years of age and 5% of those over 80 years of age,” explained Prof. Kesselring.

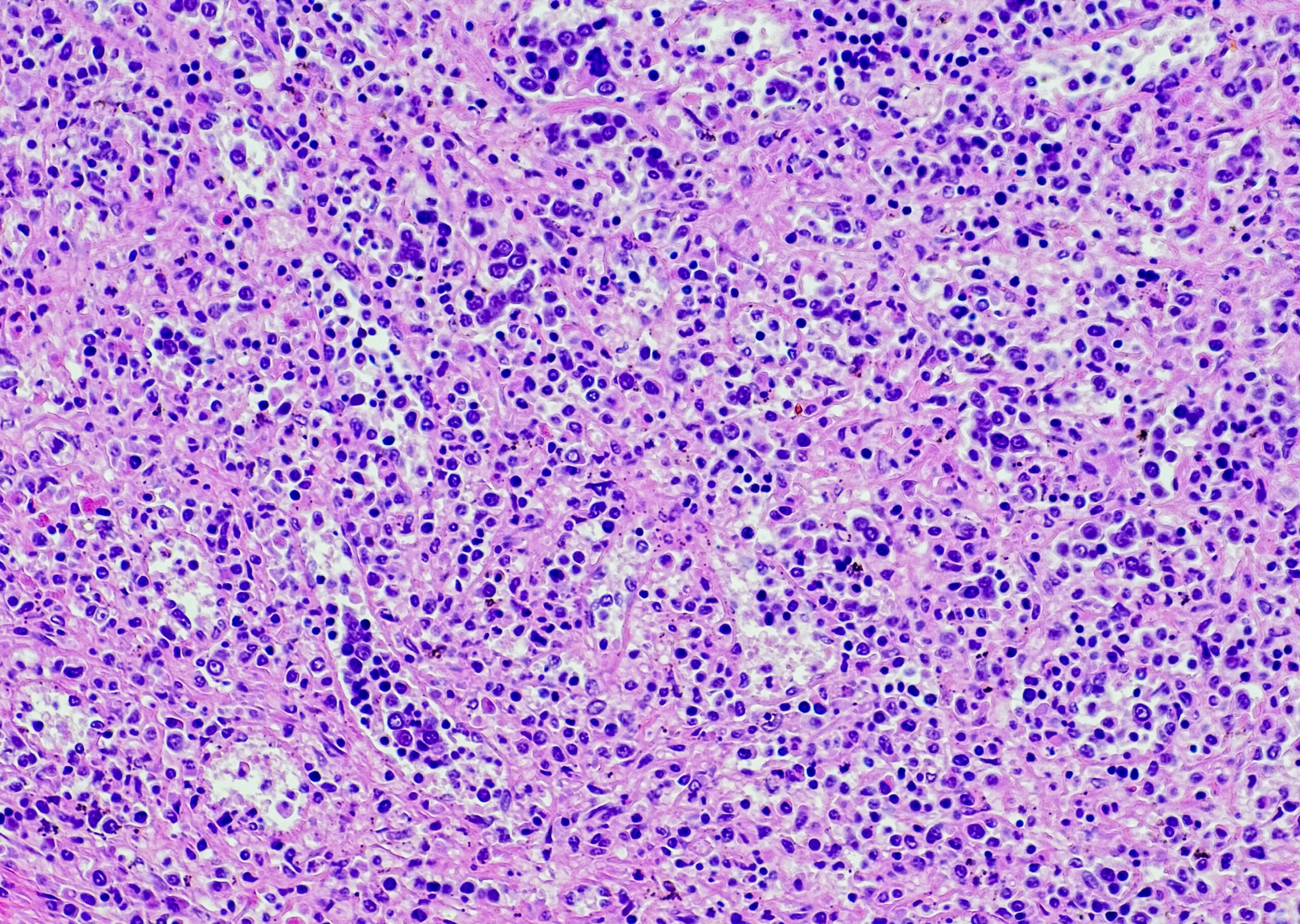

Pathophysiologically, Parkinson’s syndrome results from premature progressive degeneration of the dopamine-producing cells of the pars compacta of the substantia nigra (<1% hereditary). This results in a presynaptic dopamine deficiency in the putamen. Symptoms develop only after more than 60 percent cell loss. If they are present, the diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s syndrome is made via the finding of bradykinesis (slowed start, reduced amplitude and speed of movements) and at least one of the following symptoms:

- Rigor

- Rest tremor (4-6 Hz)

- postural instability.

Supportive criteria include unilateral onset and/or continued asymmetry in progression, resting tremor, excellent sustained response to levodopa, a slow progressive course, or marked levodopa-induced dyskinesias. In addition to the classic slightly forward bent Parkinson’s posture, there is also camptocormia (pronounced pathological trunk tilt forward when standing and walking), the so-called Pisa syndrome (laterally inclined flexion of the trunk in sitting or standing position) and antecollis (pronounced bending of the head forward).

Regulation of blood pressure in Parkinson’s disease

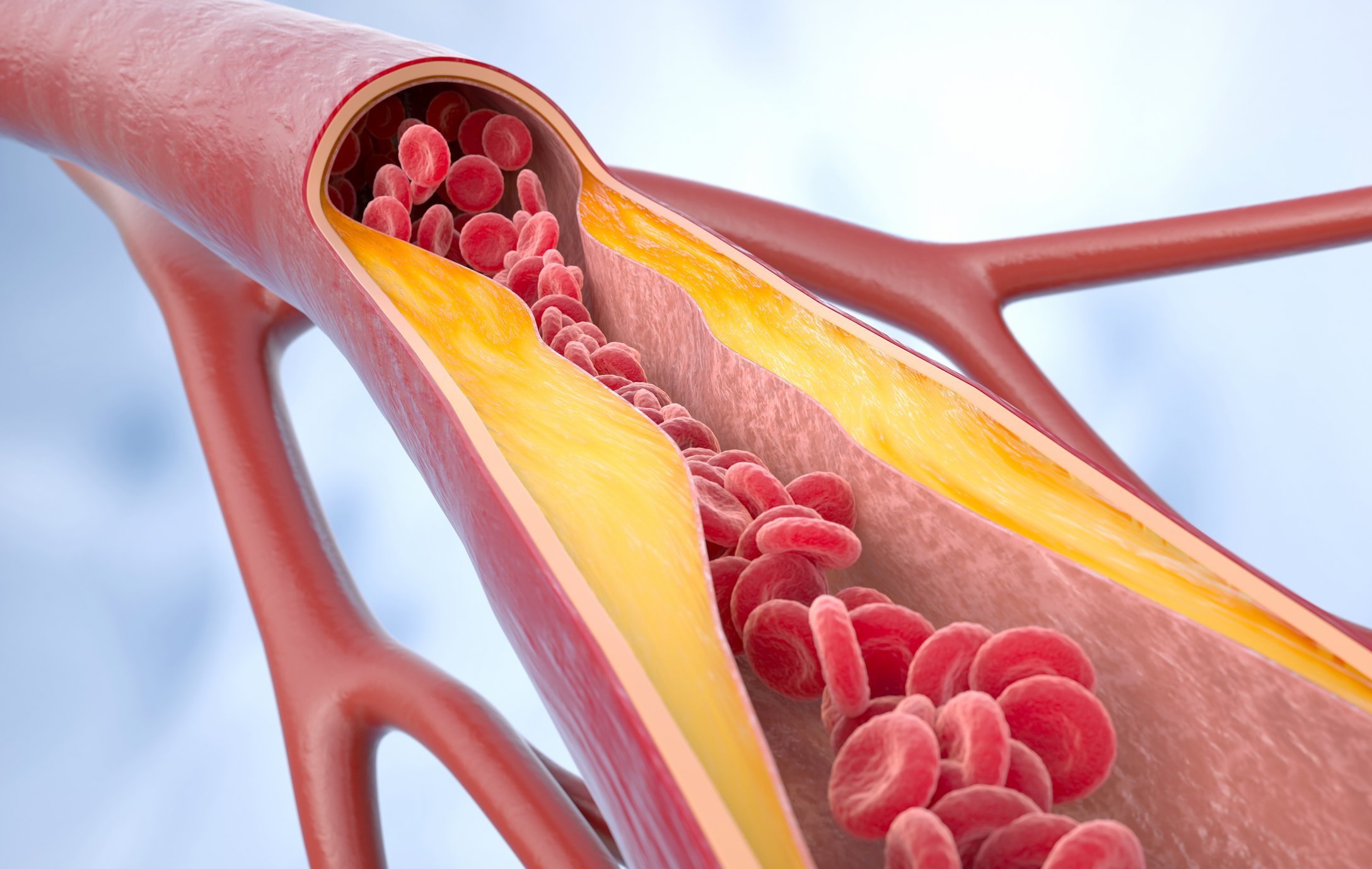

The autonomic nervous system dysfunction in Parkinson’s prevents proper adjustment of blood pressure, resulting in about half a liter of blood “pooling” in the blood vessels of the legs and pelvis due to gravity when the body is in an upright position. These blood vessels should actually be tightened immediately so that the blood pressure remains stable, but this only happens to an insufficient extent in Parkinson’s disease. Blood pressure drops in the upright position, which is called orthostatic hypotension, or too low blood pressure when standing.

Symptoms in orthostatic hypotension thus occur only in the upright position and disappear rapidly in the flat position. These include: Dizziness, unsteadiness of gait, visual disturbances (blurred vision, loss of color, tunnel vision), ringing in the ears, difficulty concentrating, fatigue or even fainting. Furthermore, pain, especially in the shoulder and neck area, and possibly a feeling of tightness in the chest may occur.

Symptoms are more frequent in the early morning hours and after food intake (reason: frequent urination during the night, drawing blood for digestion in the gastrointestinal tract). Since muscles also draw additional blood, mild physical exertion also contributes to worsening symptoms, as do heat and alcohol (blood vessels are additionally softened) and, of course, medications (including Parkinson’s medications, such as dopamine agonists).

Source: “Parkinson’s Syndrome,” lecture at Update Refresher Internal Medicine, June 16-20, 2015, Zurich.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(5): 38-39.