Back pain is one of the most common health problems and can have serious economic and psychosocial consequences. The family doctor is often the first point of contact for those affected. The correct classification of symptoms and the recognition of warning signs, which should be clarified with a specialist, is crucial.

“More than 80% of the population experiences lower back pain at least once in their lifetime,” explains Michael Gengenbacher, MD, Medical Director and Chief Physician, RehaClinic Group, at the FOMF Update Refresher in Basel [1,2]. “It’s the second most common reason someone goes to the primary care physician,” the speaker adds. The annual prevalence in the Swiss population is 20-30%, the group with the highest incidence are between 35-55 years old. Data show that 70-80% of back pain is localized in the lumbar spine [3]. According to a health economic study, lumbar back pain is the most common health problem in Switzerland and the main reason for reduced work ability [4].

Vertebral, spondylogenic, or radicular?

History and physical examination have an important diagnostic value. The mobility, function and painfulness of the affected spinal segments, the pelvis and the adjacent joints and extremities are examined. This also includes examination of skin sensation, muscle strength and reflexes. Results of imaging procedures have diagnostic relevance only in connection with the preceding diagnostic findings and medical history. Depending on the time course, one speaks of acute (<6 weeks), subacute (6-12 weeks) or chronic (>12 weeks) back pain [5]. Lumbar back pain is divided into different subtypes according to functional criteria. Lumbovertebral syndrome (LVS) is characterized by exclusive back pain. The pain is not radiating, but is limited to the area of the spine and low back. If it is a lumbospondylogenic (irritable) syndrome, the back pain radiates to the extremities. Behind this, various motor, vasomotor or vegetative disturbance patterns can be hidden. Lumboradicular (irritable) syndrome (also: lumboischialgia, “lumbago”) is characterized by back pain with dermatome-related radiation (with/without sensorimotor failure syndrome). In the context of a radicular (irritable) syndrome, pure radicular dermatoma-related pain occurs (with/without sensorimotor deficit syndrome). Causes range from disc herniation to spinal stenosis to radiculitis and other possible pathologies [1,6]. Symptoms of radicular syndrome often respond well to systemic or topical steroids.

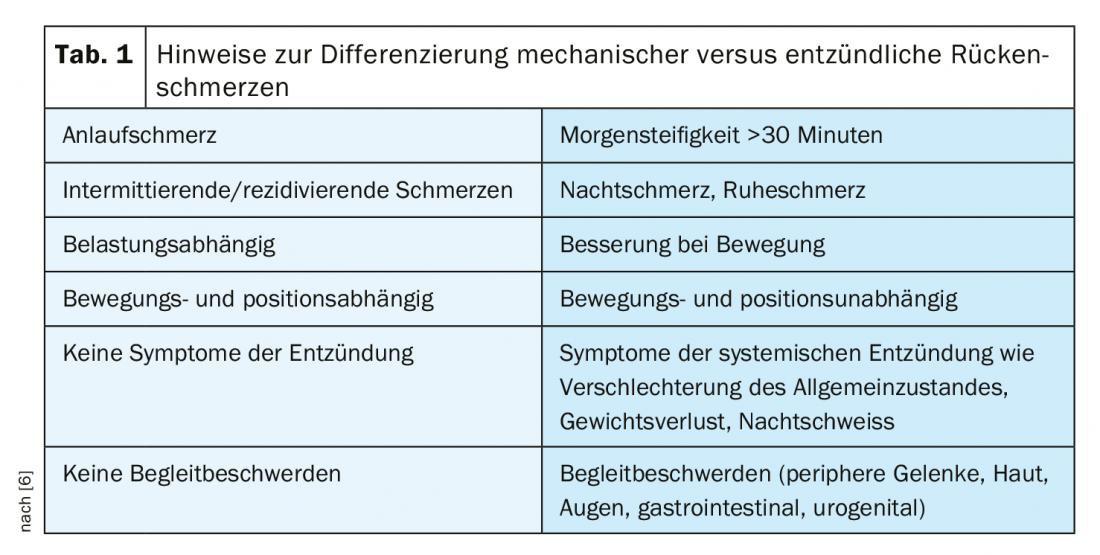

In a smaller proportion of adults, inflammatory rheumatic causes – spondyloarthropathy or spondyloarthritis – underlie lumbar back pain. Most of those affected are between the ages of 40-45 years, and a multifactorial etiopathogenesis is assumed. Non-inflammatory static-mechanical causes include myofascial syndromes (painful dysfunction of muscles), facet syndrome, SIG syndrome (sacroiliac joint syndrome), spondylolisthesis, degenerative spinal changes, symptomatic disc hernia, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyerostosis (DISH) (Rheumatism League). In order to differentiate between inflammatory and mechanically caused pain, supplementary laboratory tests can be informative in addition to anamnestic evidence (Tab. 1) .

What are the main warning signs and risk factors?

Lumbar back pain does not represent a disease entity, but is a symptom of a wide variety of causes. During the anamnestic questioning, the quality of the pain (e.g. stabbing, dull, electrifying) and the onset (sudden or insidious) should be ascertained with regard to the symptomatology. Is there evidence of an inflammatory process or is the pain more mechanical in nature (Table 1)? Also important is consideration of influencing factors such as position, load, activity, and time of onset of pain. The question of trigger factors and the duration of pain attacks or a pain problem as well as possible diurnal variations is also valuable diagnostic information. To quantify the pain episodes, one can use the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) as a tool.

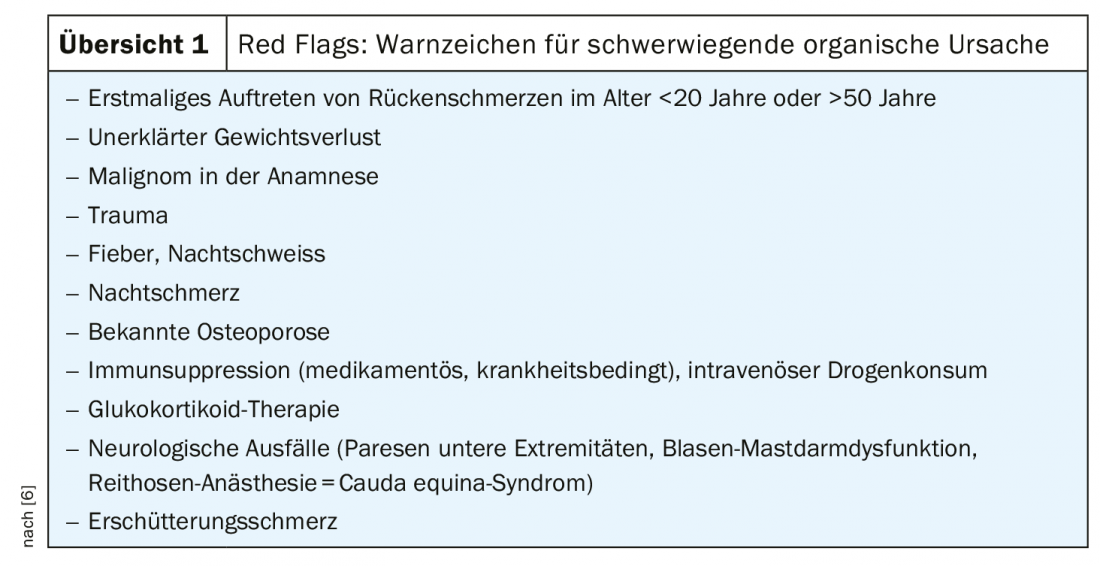

“Red flags” are warning signs of a serious organic cause of back pain that require rapid further evaluation [6]. The following criteria are possible warning signs (overview 1): Age <20 or >50 years, inflammatory symptoms, internal medicine problems, neurologic disorder. The Swiss Rheumatism League recommends the immediate and targeted use of imaging techniques in diagnosis when “red flags” are present, but in all other cases only from the 6th week after the onset of pain. It has been shown that imaging in back pain is generally of limited value and there are relatively frequent structural abnormalities on MRI even in healthy individuals [7].

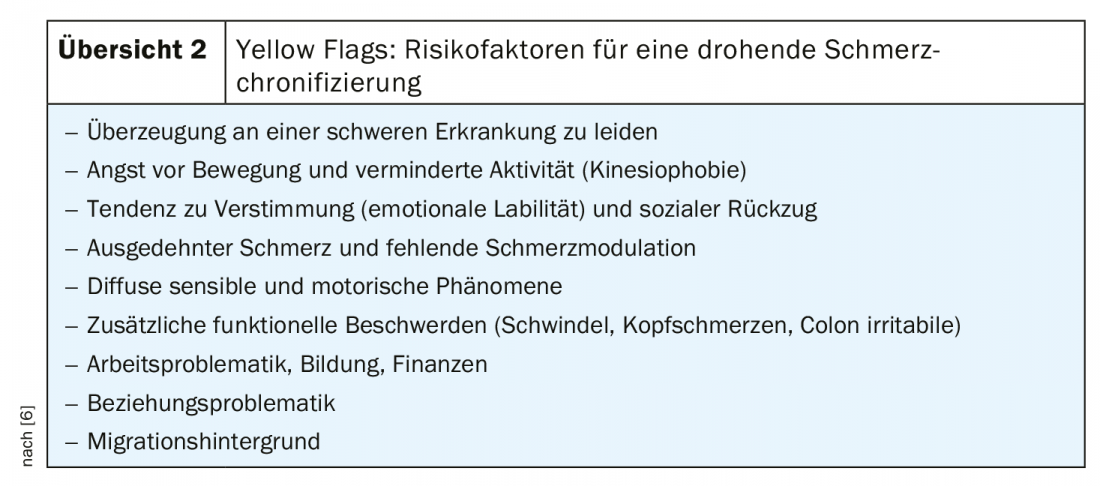

“Yellow flags” are factors that increase the risk of pain chronification [6] (review 2). These include negative attitude/attitude (e.g., fear of disability), depressed mood, and passive behavioral tendency with decreased activity and a fear-avoidance behavior pattern. With regard to social environment, withdrawal behavior and an overprotective family or lack of support are critical aspects. Regarding occupational situation, physically demanding work and shift work as well as social or other problems at work and demotivation are among the risk factors for chronicity. Financial problems can also have an unfavorable effect.

Pain relief and promotion of mobility as therapy goals

The back is a very complex system of vertebrae, intervertebral discs, ligaments, muscles and a dense network of nerve fibers that is inextricably linked to the perceptual and control functions of the brain. If there is an imbalance in one area, it can lead to muscle tension and pain in a completely different area. Muscle tension leads to pain, which in turn leads to further tension and poor posture – a vicious circle. If anxiety is involved, this can exacerbate the issue by increasing tension and pain, which in turn feeds anxiety. Primary goals of back pain treatment are relief of pain symptoms, improvement of mobility, muscular and fascial function, and daily living skills. In addition, the aim is to increase quality of life and modulate pain processing [1]. Various therapy options are available, some of which can be combined. Regarding pharmacotherapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used in moderate to high doses for short periods, selectively or nonselectively, but are contraindicated in heart failure NYHA II and above [8]. Paracetamol is not suitable for back pain due to lack of efficacy, as shown by the review of a meta-analysis [9]. For muscle dysfunction and myofascial syndrome, the myorelaxant methocarbamol has proven effective [10]. In the field of non-drug treatment options, the use of manual medicine and exercise therapy is recommended [1]. From the spectrum of movement therapy measures, the strongest evidence is available for activation therapy (active and passive physiotherapy). Short-term rest and relief when needed can also help relieve symptoms.

Literature:

- Gengenbacher M: Leitsymptom Rückenschmerz, Michael Gengenbacher, MD, RehaClinic Group, slide presentation, FOMF Basel 30.01.2020.

- Santos-Eggimann B, et al: One-year prevalence of low back pain in two swiss regions: estimate from the population participating in the 1992-1993 MONICA project. Spine 2000; 25(19): 2473-2479.

- Bork H: Non-specific back pain. Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery up2date 2017; 12(06): 625-641.

- Weiser, et al: Cost of low back pain in Switzerland in 2005. Eur J Health Economy 12: 455-467.

- Ganepour B: Back pain: causes, diagnosis, exercises and therapy. Orthopedic Joint Clinic, https://gelenk-klinik.de/wirbelsaeule/rueckenschmerzen-richtig-erkennen-und-behandeln.html

- Rheumaliga Schweiz: Update Rheumatologie 2019, Rückenschmerzen: In 15 Minuten zur klinischen Diagnose. www.rheumaliga.ch

- Luomajoki H. Six correct: using the test battery to examine lumbar motion control. Manual Therapy 2012; 16: 220-225 Manual Therapy 2012; 16: 220-225, www.thieme.de

- National health care guideline on back pain. German Medical Association (BÄK), German Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (AWMF), www.awmf.org

- Machado GC, et al: Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ 2015; 350: h1225.

- Emrich OMD, et al: Methocarbamol for acute low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. MMW Fortschr Med 2015; 157(Suppl 5): 9-16.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(5): 22-24