The number of very old individuals with dementia is drastically increasing. The frailty of this age subgroup may translate into clinical and therapeutic particularities, among others, with regard to Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). A systematic review was conducted by searching the Medline database using the following keywords: «dementia» AND («oldest» OR «very old») AND («psychiatric» OR «behavio(u)ral» OR «BPSD»). After manual inspection of the titles and abstracts of the 292 hits, seven papers were selected for further review. BPSD seem to be more common in the oldest-old than in younger individuals. Psychotic symptoms are common in the oldest-old, with dementia with delusion being the most common, especially in individuals with vascular dementia. Depression and anxiety are also common, yet likely to be underrecognized in the oldest-old with dementia. The lack of knowledge on the psychiatric aspects of dementia in the oldest-old underlines the crucial need for further research.

In most high-income countries, the number of «very old» individuals aged at least 85 years [1] or at least 90 years [2], depending on the exact definition used, has been constantly increasing [3].

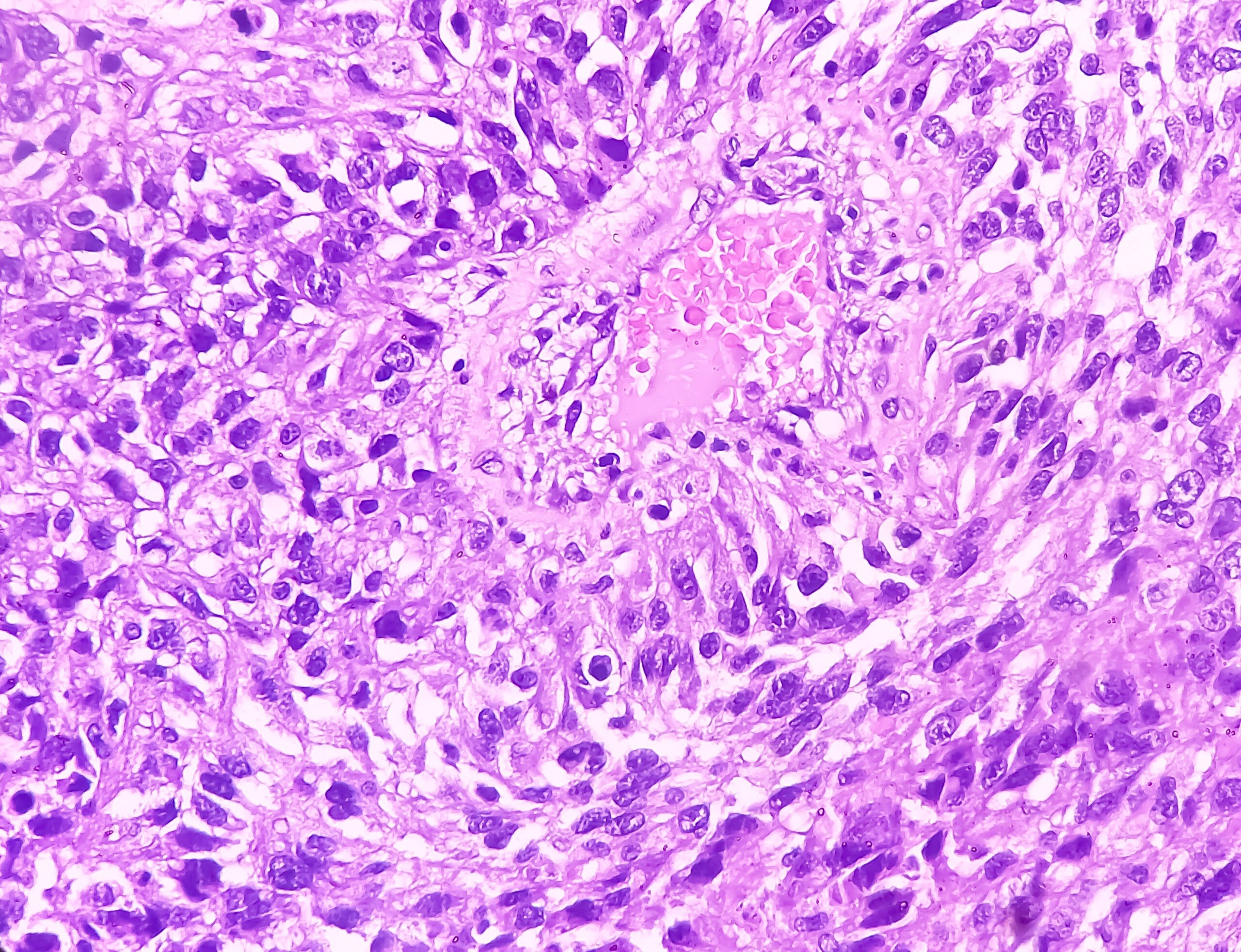

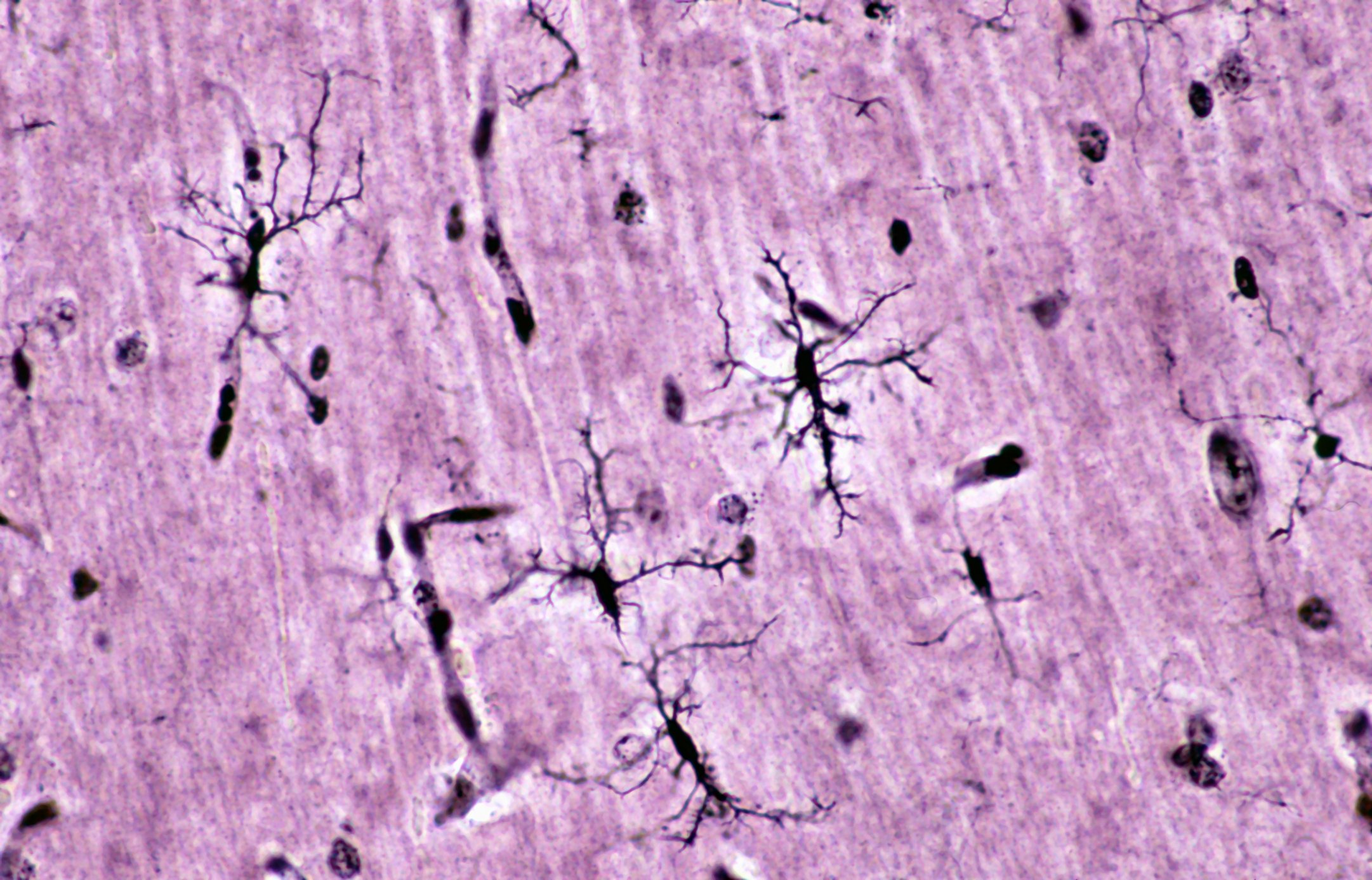

Since age represents the major risk factor for dementia, dementia is highly prevalent among this population [4]. Yet, «very old» patients are clearly under-represented in clinical research [5] and most studies about dementia suffer from an over-representation of patients under 70 [6]. Extrapolating the results of these studies to the «very old» patients should be done with caution. Indeed, this age group is characterized by a more pronounced biological, psychological and social frailty that may modify the prevalence of dementia, its clinical presentation, as well as the response to and tolerability of the various therapeutic measures [3]. Moreover, «very old» patients both with and without dementia have been reported to exhibit unique features with regard to brain histology, AD pathology [7,8] and apolipoprotein E (Apo E) [9] that may translate into clinical and therapeutic characteristics.

Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) are very common in dementia, eventually affecting up to 90% of patients with dementia [10]. BPSD encompass affective, psychotic, and behavioural components. BPSD are a source of major distress in both the patient and the caregiver and lead to complications including falls and fractures, cardiovascular complications, and the use of physical restraint [11]. BPSD are also a major risk factor for institutionalization and are associated with increased healthcare costs [10].

Thus, it appears reasonable that BPSD should be one of the main therapeutic targets in patients with dementia. This is particularly true in the oldest-old in whom the risk of institutionalization is highest, especially in the presence of behavioural disturbances [12].

The prevalence and the clinical presentations of BPSD probably vary with age. The therapeutic approaches targeting BPSD are also likely to differ in the oldest-old compared to the younger and often less frail individuals.

The aim of this paper is to systematically review published data on the psychiatric aspects of dementia in the oldest-old, with a special focus on the practical aspects in clinical practice.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review by searching the Medline database for any published papers using the following keywords: «dementia» AND «oldest» (OR «very old») AND «psychiatric» (OR «behavior(u)ral» OR «BPSD») without applying any filters. Papers were included if they referred to any psychiatric aspect in individuals with dementia over 85. Papers dealing with individuals with dementia, without individualizing a group of «very old» or «oldest-old», were not included.

Results

Medline search yielded 292 results. After manual inspection of the titles and abstracts of these results, seven papers were selected for further review.

Frequency of BPSD in the oldest-old patients with dementia: Furuta et al. [13] compared 27 very old patients with AD (onset age ≥85) with 162 less old patients (onset age <85). Although groups were comparable in terms of cognitive deficits, BPSD were more common in the oldest-old group: 96,3% of the oldest-old group had at least one BPSD (vs 82,1% of the less old group). The mean number of BPSD was also higher in the oldest-old group.

While BPSD increased with the Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) stage in the less old group, BPSD seemed to be unrelated to the stage in the «very old» group.

Psychotic symptoms in the oldest-old patients with dementia: Furuta et al. [13] specifically targeted patients with AD, delusions and delusional misidentification syndromes (not further specified), all of which were significantly more common in the oldest-old (onset age ≥85) than in the less old (onset age <85): 55,6% vs 34,0% and 48,1% vs 20,4% respectively. Visual hallucinations were much less common (3,7% in the oldest-old) and did not differ significantly between groups.

In a study involving a population-based sample of 85-year-old individuals living in Gothenburg, Sweden, the one-year prevalence of psychotic symptoms in individuals with dementia was 44,2% [14]. Over one quarter had hallucinations and around one third had delusions. Hallucinations were mostly visual (20,4% of individuals with dementia), but also auditory (in 14,3%). The prevalence of psychotic symptoms was higher in individuals with vascular dementia (53,6%) than in individuals with AD (53,9%), but this prevalence neither differed with regard to the Apo E phenotype, nor with the duration of dementia. Furthermore, the frequency of psychotic symptoms increased with dementia severity in individuals with AD, but not in individuals with vascular dementia. Hallucinations were more common in patients with a lower educational level [14].

Depression and anxiety in oldest-old patients with dementia: Fichter et al. [15] examined the prevalence of both major depressive disorder and dysthymia among individuals aged at least 85 in two community samples from Germany and the USA. Among individuals with cognitive impairment, the prevalence of major depressive disorder (0% and 2,5% in the German and American samples respectively) and dysthymia (2,4% and 3,5% in the German and American samples respectively) was rather low and tended to be higher, albeit not significantly, than that in individuals without cognitive impairment [15].

In Furuta et al. [13], the prevalence of depression and anxiety in the oldest-old (≥85 years) with dementia was 9,1% and 27,3% respectively, and did not differ from the figures in their younger counterparts (<85 years). Depression and anxiety were not among the most common BPSD, in contrast to the results of community-based studies where depression and anxiety were often reported to be the most common BPSD in the oldest-old. This discrepancy is likely due to different study populations: old-age psychiatry patients are more likely to exhibit more severe BPSD, including psychosis and behavioural disturbances, than community-dwelling individuals; and BPSD were not distinguished from possible concomitant affective disorders in most community-based studies [13].

In a population-based study in Sweden involving individuals over 85, depression was more common in those with dementia than in those without (43% vs 24%). Among the individuals with dementia, depression was not associated with any of the sociodemographic or clinical factors, except the loss of a child in the past ten years [1]. This is in contrast to the group without dementia, where depression was associated with several sociodemographic and clinical factors (including loneliness, inability to go outside, the use of analgesics, and a higher total number of medication). Furthermore, the response to antidepressants was slightly worse in the demented group in comparison with the non-demented one [1]. These findings suggest that the causal determinants of depression in people with dementia can be different from those in people without dementia, with a likely greater role of brain pathology in the genesis of depression among demented patients [1]. Depression as a BPSD should also be distinguished from primary depression co-occurring with dementia. Etiopathogenic aspects are very likely to be different, which may give the impression that response to certain therapeutic options should be different too.

Mall et al. [16] examined psychopathological symptoms in 58 geriatric nursing home residents in Switzerland, aged at least 90. Most (89,7%) had a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of <24. The mean Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) total severity score of 6,24 ±4,60 can be considered rather low (the score range being 0–36 [17]). The most prevailing symptoms were of the depressive and anxious type, and apathy [16].

Behavioural and sleep disturbances in the oldest-old patients with dementia: In Furuta et al., irritability, excitement, delirium, reversed diurnal rhythm, and wandering were more common in the oldest-old (≥85) than in the less old (<85) group [13]. Hori et al. [3] studied behavioural signs in AD inpatients admitted for the first time because of behavioural symptoms. The authors compared the symptoms and signs among 18 patients aged at least 90 («oldest-old») with 26 inpatients (<90) with late-onset AD, matched for sex, severity of dementia, and disease duration. The oldest-old group scored higher on the items: «waking up and wandering at night» and «sleeps excessively during the day», but lower on the items «paces up and down», «gets lost outside», and «wanders aimlessly outside or in the house during the day». The authors explain this discrepancy with Furuta et al.’s findings of a more advanced cognitive impairment in their sample [3].

Etiopathogeny of BPSD in the oldest-old patients with dementia: There is hardly any literature on etiopathogeny of BPSD in the oldest-old with dementia. Response to antidepressants has been shown to be worse in the oldest-old with dementia, likely reflecting different etiological factors [1]. Moreover, among the oldest-old with dementia, depressive BPSD likely depend on an etiopathogenic basis other than the one explaining primary depression (which may co-occur with dementia). However, further studies are needed to confirm these hypotheses.

Particular options in the management of BPSD in the oldest-old patients with dementia: Studies on the treatment or management of psychiatric features in the oldest-old with dementia are few and far between. We found only one study which individualized a group of oldest-old patients in a clinical trial of opioids in the treatment of agitation in dementia: Manfredi et al. [18] hypothesized that opioids might prove useful in treating agitation in patients with severe dementia, particularly the very old. Indeed, since patients are often unable to convey the experience of pain verbally, pain is often unrecognized as a cause for agitation. In their double-blind placebo-controlled cross-design study, they showed that opioids were more effective than placebo in decreasing agitation only in patients over 85. This result persisted after adjusting for sedation. The effects of opioids on agitation in very old patients with severe dementia might be explained by the analgesic effects on an unrecognized pain and/or by a direct effect on the patients’ behaviour [18]. However, though positive effects have been found in general samples [19], the effect of analgesics on agitation is inconsistent in such samples [20].

Even though BPSD treatment is likely to differ to some degree in the oldest-old group, the scarcity of the data set and the weak evidence are prompting clinicians to refer to more general guidelines [20] and to alter their view after carefully assessing each patient.

Conclusion

Data published on the psychiatric aspects of dementia in very old individuals remains strikingly sparse. Clinicians might assume that the clinical presentations and the therapeutic options described among the population of patients with dementia as a whole should also apply to the very old age group. Nonetheless, biological and psychosocial features distinguish the very old with dementia from their younger counterparts, thus making the a priori extrapolation of general findings to this specific and frail subgroup unfounded and possibly hazardous.

BPSD seem to be more common in the oldest-old than in younger individuals. However, the exact figures of prevalence varied widely from study to study, depending mainly on the population under investigation (community vs nursing home residents, vs psychiatric outpatients, vs psychiatric inpatients). Psychotic symptoms are common in the oldest-old with dementia (with delusion being the most common), especially in individuals with vascular dementia. Depression and anxiety are also frequent, yet likely underrecognized in the oldest-old with dementia.

A double-blind trial, the only study identified which specifically assesses the oldest-old [18], showed that opioids may be effective in treating agitation in the very old, but not in younger patients with severe dementia. Artful and mostly non-evidence-based treatment approaches in this age group remain, for the time being, the only option.

Research targeting the very old with dementia is urgently needed, especially since the number of this population is rapidly rising in most parts of the world.

References:

- Bergdahl E, et al.: Depression among the very old with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics/IPA 2011; 23(5): 756–763.

- Yang Z, et al.: Dementia in the oldest old. Nature Reviews Neurology 2013; 9(7): 382–393.

- Hori K, et al.: First episodes of behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients at age 90 and over, and early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: comparison with senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2005; 59(6): 730–735.

- Jorm AF, et al.: The prevalence of dementia: a quantitative integration of the literature. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 1987; 76(5): 465–479.

- Lucca U, et al.: A Population-based study of dementia in the oldest old: the Monzino 80-plus study. BMC Neurology 2011; 11: 54.

- Schoenmaker N, et al.: The age gap between patients in clinical studies and in the general population: a pitfall for dementia research. The Lancet Neurology 2004; 3(10): 627–630.

- Giannakopoulos P, et al. Dementia in the oldest-old: quantitative analysis of 12 cases from a psychiatric hospital. Dementia 1994; 5(6): 348–356.

- von Gunten A, et al.: Brain aging in the oldest-old. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/358531. Epub 2010 Jul 25.

- Juva K, et al. APOE epsilon4 does not predict mortality, cognitive decline, or dementia in the oldest old. Neurology 2000; 54(2): 412–415.

- Feast A, et al.: Behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia and the challenges for family carers: systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2016; 208(5): 429–434.

- Raivio MM, et al.: Neither atypical nor conventional antipsychotics increase mortality or hospital admissions among elderly patients with dementia: a two-year prospective study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2007; 15(5): 416–424.

- Cepoiu-Martin M, et al.: Predictors of long-term care placement in persons with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; Apr 4. doi: 10.1002/gps.4449. [Epub ahead of print]

- Furuta N, et al.: Characteristics of behavioral and psychological symptoms in the oldest patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatrics 2004; 4[1]: 11–16.

- Ostling S, et al.: Psychotic symptoms in a population-based sample of 85-year-old individuals with dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2011; 24[1]: 3–8.

- Fichter MM, et al.: Cognitive impairment and depression in the oldest old in a German and in U.S. communities. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 1995; 245(6): 319–325.

- Mall JF, et al.: Cognition and psychopathology in nonagenarians and centenarians living in geriatric nursing homes in Switzerland: a focus on anosognosia. Psychogeriatrics 2014; 14[1]: 55–62.

- Cummings JL, et al.: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44(12): 2308–2314.

- Manfredi PL, et al.: Opioid treatment for agitation in patients with advanced dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2003; 18(8): 700–705.

- Cummings JL, et al.: Effect of Dextromethorphan-Quinidine on Agitation in Patients with Alzheimer Disease Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2015; 314(12): 1242–1254.

- Savaskan E, et al.: [Recommendations for diagnosis and therapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD)]. Praxis 2014; 103(3): 135–148.

InFo NEUROLOGIE & PSYCHIATRIE 2016; 14(5): 12–14