Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a serious hyperglycemic complication in people with diabetes. Physicians in sub-Saharan Africa conducted a prospective cohort study of adults newly diagnosed with diabetes who developed DKA and in whom the phenotype was described. It is one of the few studies worldwide in which insulin withdrawal was systematically attempted.

In most cases, diabetic ketoacidosis is the first symptom of type 1 diabetes. However, DKA can also develop in people with type 2 diabetes under stressful conditions such as infection, after surgery or trauma. In addition, DKA can also occur in people who have recently been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes without a triggering cause. Typical for this group of people, whose clinical picture with severe hyperglycemia and ketosis is similar to that of classic type 1 diabetes, is that they are able to discontinue insulin therapy and control blood glucose levels with a diet and/or oral glucose-lowering medication for a period of time.

There is no consensus on how to classify people with this form of clinical presentation, with varying arguments as to whether they should be categorized as a variant of type 1 or type 2 diabetes, or as a subcategory called ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes (KPT2D). In the 2019 WHO classification, this type of disease is categorized as “hybrid diabetes”. The heterogeneity of DKA patients is considerable and there is a lack of standardization in the phenotyping of participants in long-term follow-up studies. However, people with KPT2D generally have a low risk of recurrent ketoacidosis, and the clinical course after the first DKA is similar to that of people with type 2 diabetes and does not represent a distinct subtype.

The “Aβ system” as the best prediction scheme

Classification of individuals presenting with DKA is useful for planning future treatment strategies, but can be difficult at initial presentation due to the increasing prevalence of obesity in individuals diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and the recognition that in some populations KPT2D may be the most common form of diabetes in adults with DKA. The best scheme for predicting the phenotype of future insulin independence is the “Aβ system”. This regimen has not been extensively evaluated and may be less reliable in other populations; in addition, such a test may not be available in many low-income countries worldwide.

Associate Professor Peter J. Raubenheimer of the Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, South Africa, and colleagues conducted a prospective, descriptive cohort study of all individuals aged 18 years or older presenting for the first time with DKA at four public hospitals in the Groote Schuur Academic Health Complex [1]. Clinical, biochemical and laboratory data, including GAD antibodies and C-peptide status, were collected at the beginning of the study. Insulin was systematically reduced and discontinued in patients who achieved normoglycemia within a few months after DKA. Patients were followed up for 12 months and then annually for up to five years after the first occurrence of ketoacidosis.

KPT2D as the predominant phenotype

Of the 118 people who presented to the clinics with DKA for the first time, 88 patients who had recently been diagnosed with diabetes at the time of DKA were finally included in the study and followed up for five years. In this cohort of adults, the most common phenotype was type 2 diabetes or the A-β+ phenotype (antibody-negative, C-peptide-positive) in the Aβ classification. Most were overweight, the median (IQR) BMI at diagnosis was 28.5 (23.3-33.4) kg/m2, and there were no obvious predisposing factors for DKA. The four Aβ groups differed significantly from each other phenotypically in terms of BMI, the presence of acanthosis nigricans, the severity of acidosis at first presentation with DKA and the lipid profile (HDL cholesterol and triglycerides). Overall, 46% of participants did not require insulin 12 months after diagnosis and 26% were still insulin-free 5 years after diagnosis; in the A-β+ group, 68% were insulin-free at 12 months compared to none of the participants in the A+β- group, nine (41%) in the A-β- group and three (33%) in the A+β- group. The insulin-free rate in the A-β+ group was still 37% after 5 years.

Predictors of insulin freedom at 12 months included older age, the presence of acanthosis nigricans and the absence of anti-GAD antibodies. Only the presence of acanthosis nigricans was still a useful predictor of insulin non-requirement 5 years after diagnosis. After stopping the insulin, however, there was a gradual deterioration in blood glucose control, as is to be expected in people with type 2 diabetes.

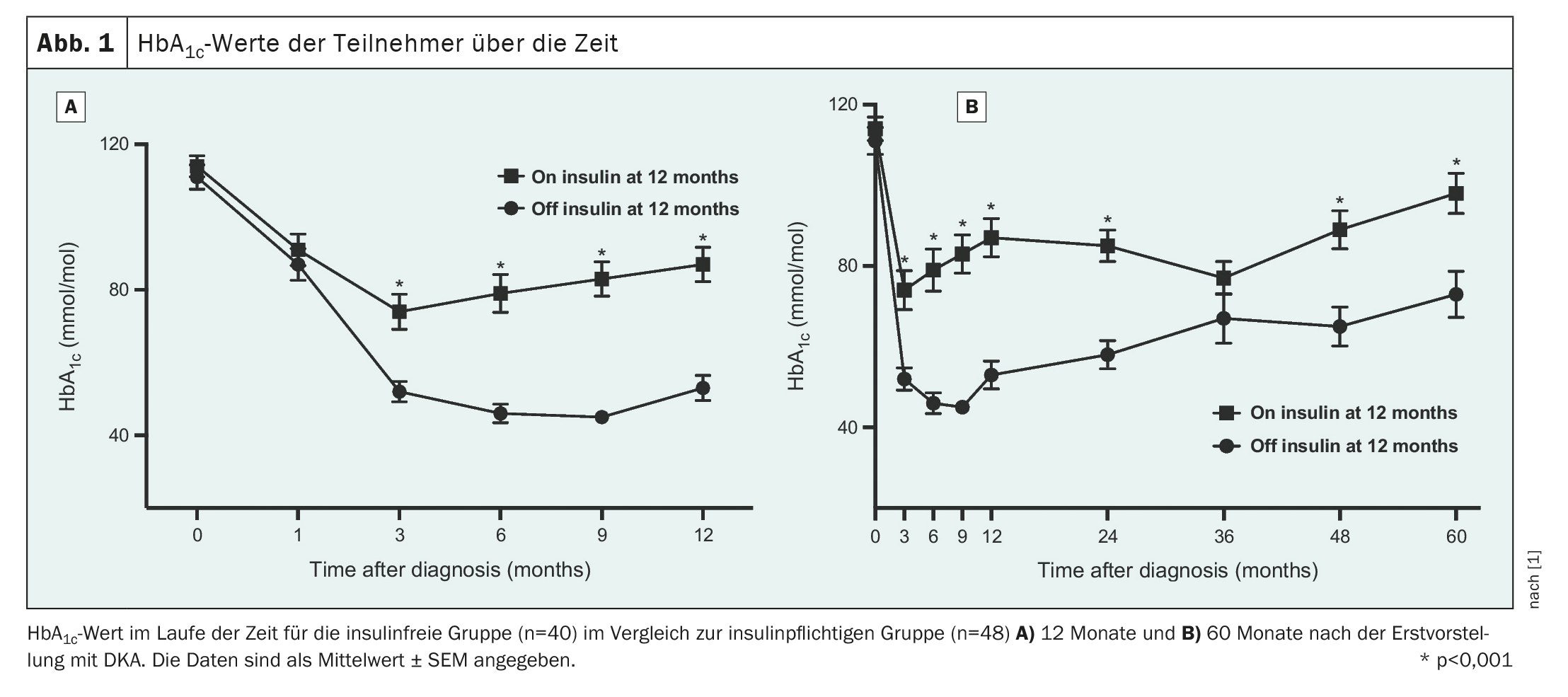

During the 12-month follow-up period, the HbA1c values of the participants in whom insulin could be discontinued (off-insulin group) and the participants in whom insulin could not be discontinued (on-insulin group) differed from each other after 3 months and remained significantly different (Fig. 1); there were no differences between the Aβ groups after 12 months.

Results may not be transferable to other populations

Assoc. Prof. Raubenheimer and colleagues point out that the study has several limitations and that validation in other populations is important. Thus, the cohorts were recruited only in the Cape Town metropolitan area, and the results may not be transferable to rural or other areas of Africa with high genetic and phenotypic variability in type 2 diabetes. In addition, no white people were recruited in this study, so it was not possible to determine whether ethnicity was a strong predictor of insulin independence. The authors explain that they did not have access to the zinc transporter 8 antibody test, which might have identified a few more people with type 1 diabetes. However, they emphasize that the positivity rate in South Africa is probably much lower than in a European population.

The predominant phenotype of the adults who presented with a first episode of DKA in Cape Town, South Africa, was ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes, the scientists summarize. Consequently, many adults with diabetes diagnosed at the onset of DKA (“diabetes of ketosis onset”), especially those with the obesity phenotype with acanthosis nigricans and without anti-GAD antibodies, could be safely weaned off insulin using a standardized protocol. Almost a third of these people could be treated without insulin for 5 years, avoiding the additional burden, potential risks and costs of insulin therapy, at least for some time. Classic type 1 diabetes (lower weight, antibody positivity, low or undetectable C-peptide levels and long-term insulin dependence) was less common. The simple clinical sign of acanthosis nigricans is a strong predictor of insulin independence 12 months and 5 years after initial presentation. In the future, phenotypic and genotypic classification systems could enable a better aetiological diagnosis of diabetes and better strategies for optimal individualized treatment.

Take-Home-Messages

- The most common diabetes subtype in people who have DKD at the time of diabetes diagnosis is ketosis-prone diabetes.

- In 46% of these people, insulin could be discontinued within 12 months; 26% of the patients were still insulin-free 5 years later.

- The presence of acanthosis nigricans was the strongest predictor of short- and long-term insulin independence.

- Greater awareness could lead to better assessment of patients in the future, potentially avoiding the long-term use of insulin.

Literature:

- Raubenheimer PJ, Skelton J, Peya B, et al: Phenotype and predictors of insulin independence in adults presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 2024; 67: 494-505; doi: 10.1007/s00125-023-06067-3.

InFo DIABETOLOGY & ENDOCRINOLOGY 2024; 2(1): 18-19