Anxiety disorder should be thought of in the presence of previous anxiety disorders, somatic anxiety symptoms, recent traumatic experiences, or avoidance of social situations. Assessment of anxiety disorders should include type, duration, symptom severity, and functional impairment. In addition, the presence of influencing and risk factors should be clarified. Regardless of the condition, NICE requires that the least intrusive but most effective therapy be offered. Thus, evidence-based psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for anxiety disorders. The German guidelines allow for an individualized treatment plan according to patient preference, previous treatment attempts, severity, comorbidity, substance use, and suicide risk, given equivalent evidence for psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy as well as for the combination of both methods. Response to therapy should be evaluated and documented during each session.

Although the Swiss Recommendations for the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders [1], the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines. [2,3], the S3 guideline of the German Society for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology (DGPPN) [4] and the standards published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. [5–7] were published more than two years ago, the evidence base has not changed in the meantime. This article thus serves as a knowledge refresher.

Epidemiology

According to current estimates, anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent mental illnesses worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence between 13% and 17% [8]. Women are affected more than twice as often as men. They already occur in childhood and adolescence. In adults, they usually manifest between the ages of 35 and 55. The 12-month prevalence is 10% for specific phobias, agoraphobia/panic disorder 6%, social phobia 3%, and generalized anxiety disorder 2%.

Quality management

Quality management [7] to identify and treat anxiety disorders is the basis of good care. Because anxiety is also a regulative physiological response, the detection rate is often poor. Only a minority of those affected therefore receive adequate treatment. If anxiety disorder and depression occur together, often only the depression is recognized and treated. If an anxiety disorder is identified, it is usually treated pharmacologically. To provide the best possible care, NICE postulates four quality standards [7]:

- QS 1: Potential anxiety disorders require a detailed assessment to clarify diagnosis, symptom severity, and functional impairment.

- QS 2: Anxiety patients should be treated primarily with evidence-based psychotherapy.

- QS 3: Anxiety patients should be prescribed benzodiazepines or antipsychotics only in exceptional circumstances.

- QS 4: Response to therapy should be evaluated and documented during each session.

Assessment and diagnosis

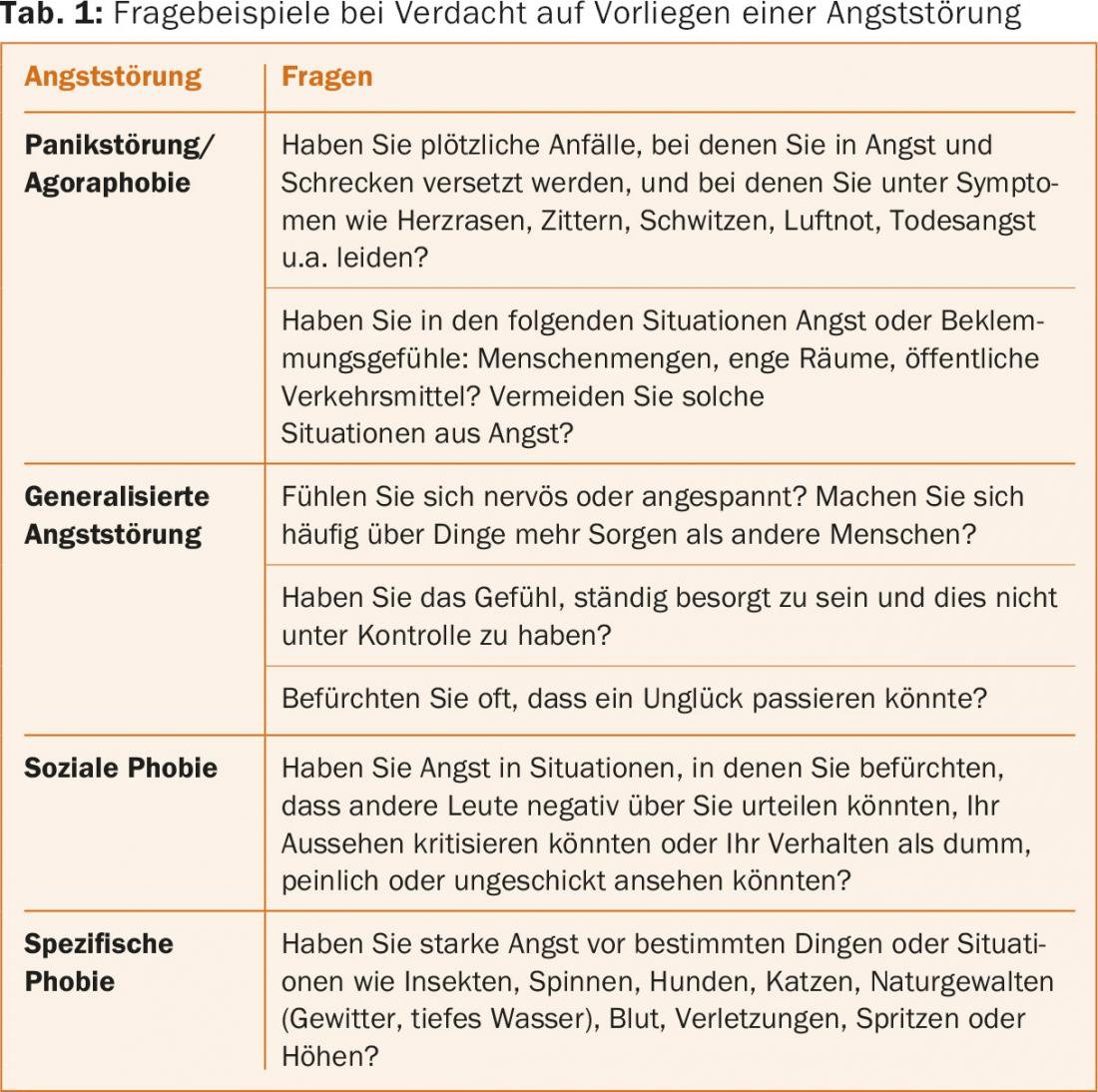

Sufferers are more likely to talk about pain, sleep disturbances, or other somatic complaints than their actual anxiety symptoms. You should therefore think of an anxiety disorder if you have previous anxiety disorders, somatic anxiety symptoms, recent traumatic experiences, or avoidance of social situations. If you suspect an anxiety disorder, the questions in Table 1 will help you clarify.

Differential diagnoses include psychiatrically different anxiety disorders, depression, and somatoform disorders. As causative physical ailments, they are cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases, neurological diseases or endocrine disorders. In cases of high reciprocal comorbidity, a distinction is also made between primary and secondary anxiety disorders. Primary anxiety disorders are not based on other diseases, secondary ones have one as a cause. Primary anxiety disorders may condition comorbid depression. Comorbidity is prognostically unfavorable because of poorer response to therapy, usually more side effects, and worse remission.

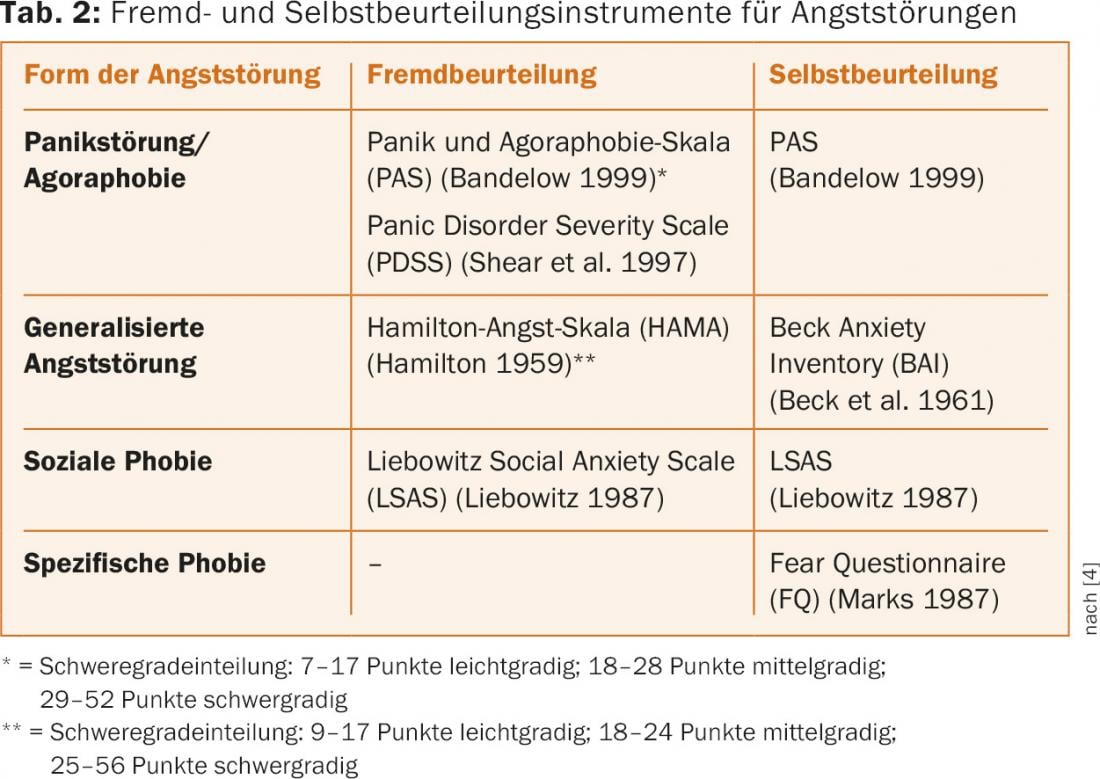

Assessment of anxiety disorders should include type, duration, symptom severity, and functional impairment. In addition, the presence of relevant influencing and risk factors should be clarified: History of mental and chronic somatic disorders; family history; previous treatment attempts and experiences; social history; relationship quality; social isolation; sexual abuse; experience of violence; socioeconomic situation and migration background. If social anxiety disorder is suspected, the presence of avoidant personality disorder, substance abuse, affective disorder, psychosis, and autism should also be assessed. Supplementary psychometric self- or third-party assessment instruments quantify the symptomatology and are suitable for progress diagnosis or outcome measurement (Tab. 2).

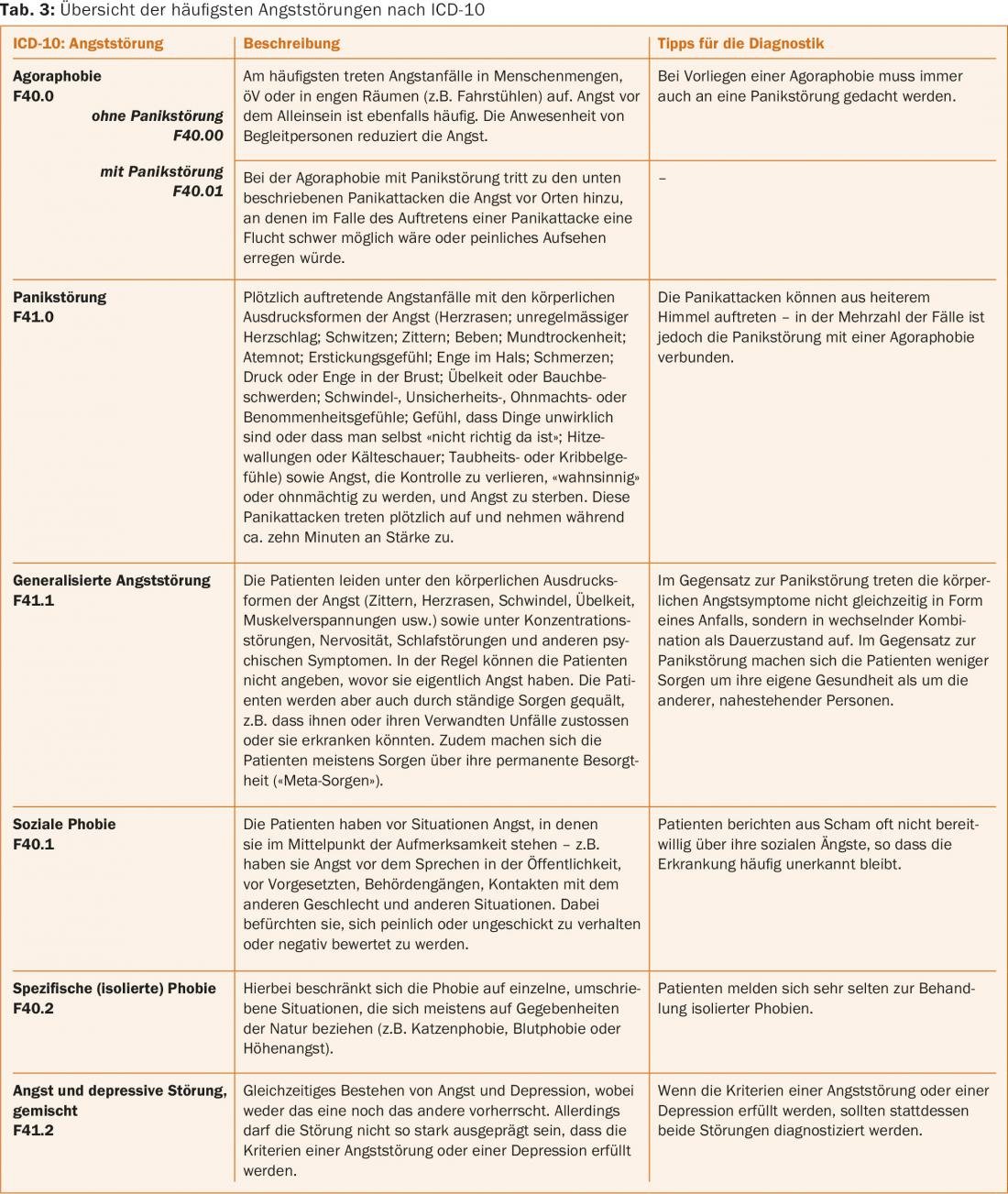

Diagnostic assessment is performed using the International Classification of Mental Disorders ICD10 Chapter V (F) [9]. We refer here to agoraphobia/panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobias and specific phobias as anxiety disorders in the narrow sense (Tab. 3).

Therapy recommendations

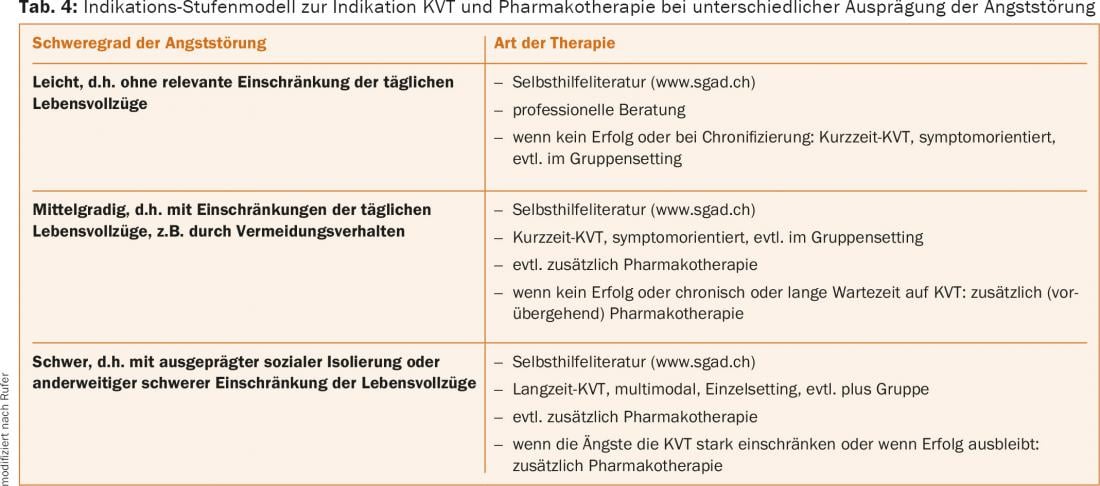

Regardless of disease, NICE calls for the least intrusive but most effective therapy to be offered before resorting to therapies with less favorable therapeutic outcomes/side effect profiles. Thus, evidence-based psychotherapy is the first choice for anxiety disorders. The German guidelines allow individual treatment planning according to patient preference, previous treatment attempts, severity, comorbidity, substance use, and suicide risk, given equivalent evidence for psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy as well as for the combination of both methods (Tab. 4).

Evidence-based psychotherapy

Evidence-based psychotherapies are the treatment of choice with largely no side effects and better relapse prevention. For anxiety disorders, they range from support groups to high-frequency psychotherapy. They are usually offered on an outpatient basis. Only very severe disorders should be treated as inpatients. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has good evidence for all four anxiety disorders, making it psychotherapy of choice. KVT should be conducted according to empirical treatment manuals. Exposure therapy should be performed if avoidance is high. Compared to CT, the evidence base for psychodynamic therapies is less good in terms of study numbers and methodological quality. In direct comparative studies, CT was superior to psychodynamic approaches in anxiety treatment. Psychodynamic therapy should therefore be offered only when CT has not been effective. The duration of therapy is measured individually according to the severity of the disease, comorbidity and psychosocial conditions. Individual therapies are superior to those in groups. Only in cases of social phobia is group self-confidence training indicated. Evidence is insufficient for other forms of psychotherapy such as applied relaxation, interpersonal therapy, or client-centered talk therapy as the main therapy.

Psychopharmacological interventions

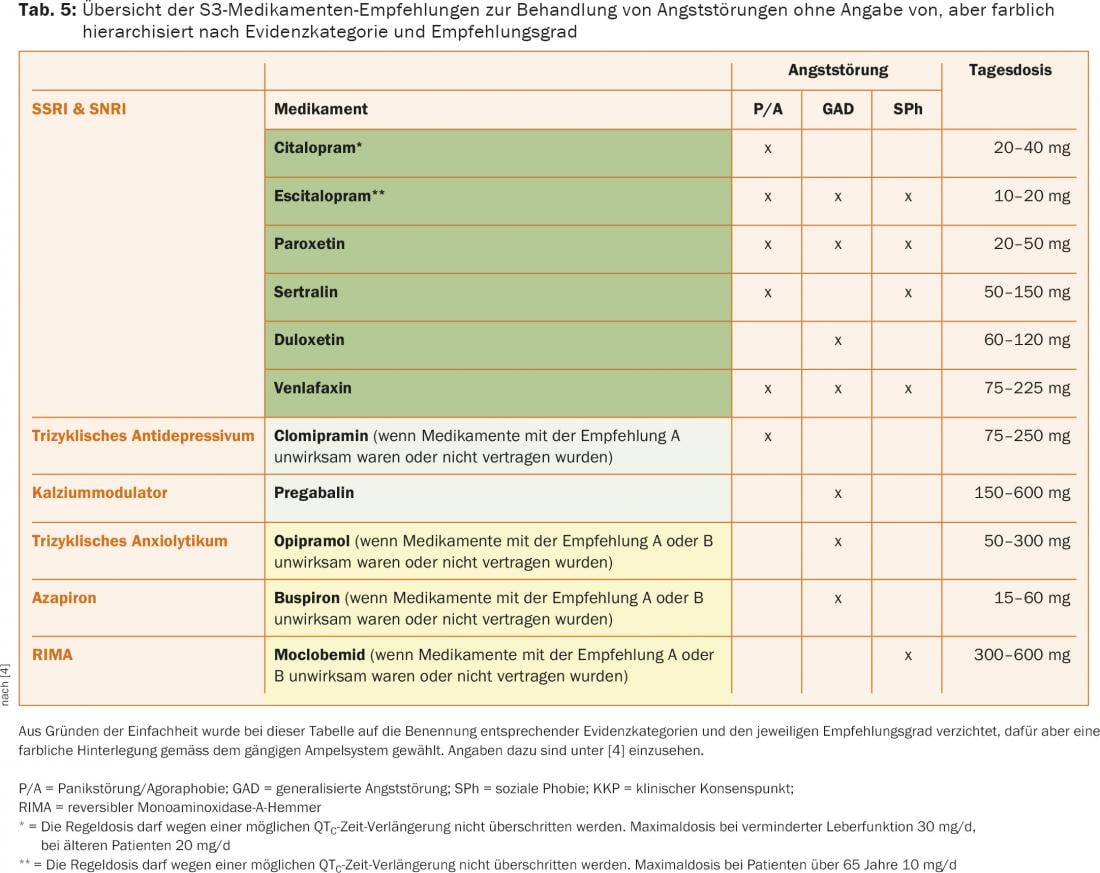

Pregnancy, severe heart disease, or advanced age should be considered when selecting medications. Patients should be advised of the delayed onset of action of antidepressants (one to six weeks) and the required duration of use (at least six months). Guideline-based first choice (A recommendation: “should”; highlighted in dark green in Table 5) are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). The tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine (panic disorder) and the calcium modulator pregabalin (GAS) have a B recommendation (“should”/light green background). The reversible monoaminooxidase A inhibitor (RIMA) moclobemide is used with expert consensus for social phobias if A and B substances are ineffective (highlighted in yellow). Benzodiazepines should be avoided because of the development of tolerance and dependence. Antipsychotics are also not a permanent medication because of the side effects. Both classes of substances should be given only in cases of severe heart disease, contraindication to standard medication, severe anxiety crises, or suicidality. Drug level determinations can assist in dose finding. As maintenance therapy, the dosage must be maintained unchanged. After the onset of remission, the medication is continued for six to twelve months. If anxiety recurs upon discontinuation, but also in cases of severe anxiety disorder as well as a history of prolonged need for treatment, a longer course of treatment may make sense. To avoid discontinuation phenomena, medication must be phased out (Tab. 5).

Procedure in case of therapy resistance

If ineffective, switch to another standard substance after four to six weeks. If there is a partial response, a dose increase is indicated. For this purpose, the step-by-step plan for medication change in case of non-response/intolerance is recommended. If standard medications are unsuccessful, one of the second choice may be prescribed. Legal aspects must be weighed for off-label treatments with medications not approved for anxiety disorders (Table 6).

Additions to secondary anxiety disorders

In secondary anxiety disorders, the primary disorder should first be treated as best as possible, thereby eliminating/ reducing the triggering factor. Whenever resistance to therapy under standard substances becomes apparent, the presence of a causative primary disease should be reconsidered.

Combination therapies

Studies combining psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy show therapeutic benefit in panic disorder. Studies are lacking on generalized anxiety disorder, and data are inconsistent on social phobias. Thus, if one type of therapy alone is not sufficient, the other or a combination of both can be chosen.

Evaluation and documentation

Patients should record their response to treatment during each treatment session. This allows, if necessary, to quickly adjust the treatment.

Literature:

- Keck ME, et al: The treatment of anxiety disorders, part 1: panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobias. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(34): 558-566.

- Bandelow B, et al: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders – first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry 2008; 9(4): 248-312.

- Hasan A, et al: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry 2012; 13(5): 318-378.

- Bandelow B, et al: German S3 guideline treatment of anxiety disorders. 2014. www.awmf.org/leitlinien.html

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guideline 113: Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management. 2011; revised 2015. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guideline 159: Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment. 2013; revised 2015. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg159

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Quality Standard 53: Anxiety Disorders. 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs53

- Steel Z, et al: The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014; 43(2): 476-493.

- Dilling H, et al. (Eds.): International classification of mental disorders: ICD-10 Chapter V (F). Clinical diagnostic guidelines. Huber 2011.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(4): 4-9.