In children, as in adults, wounds heal in different phases. Especially in the younger child, wound healing tends to be faster and with fewer complications. Fibroblasts are available more rapidly and granulation tissue is produced more quickly. Children have less subcutaneous adipose tissue and thus have less “dead space,” which is thought to play a role in the development of infections. In general, children have a functioning vascular system and suffer from different comorbidities than adults. These factors contribute to the fact that wounds in pediatrics usually heal primarily (sanatio per primam intentionem).

The following information and recommendations have been taken from the guidelines of the pediatric clinics at the Inselspital Bern and adapted for use in practice.

Developmental factors play a major role in the development of acute wounds in children. In the immature skin of the premature infant, for example, a simple patch removal is enough to cause an epidermal tear due to insufficient adhesion of the skin layers. The skin in the diaper area is prone to diaper dermatitis, erosion, and ulceration in infants. As children grow older, they acquire traumatologic wounds (abrasions, abductions, cuts, punctures, bites, lacerations, or thermal injuries). The surgical wound as an iatrogenic wound represents another type of wound in pediatrics.

A wound is said to be chronic if, despite causal and appropriate local treatment, there is no healing tendency within two to three weeks.

Pediatric wound care differs in some respects from the adult approach. Studies on wound treatment products are primarily conducted in adults, so ingredients in products should be critically reviewed before use in children. Often, dressings designed for adults need to be cut to the correct size and dosages of topical products adapted before use in pediatrics. Bandages must be applied in such a way that they hold with the moving child and cannot be removed by the child himself. In addition, the prevention and treatment of pain, anxiety and stress should be given a particularly high priority in wound care.

General principles of wound treatment

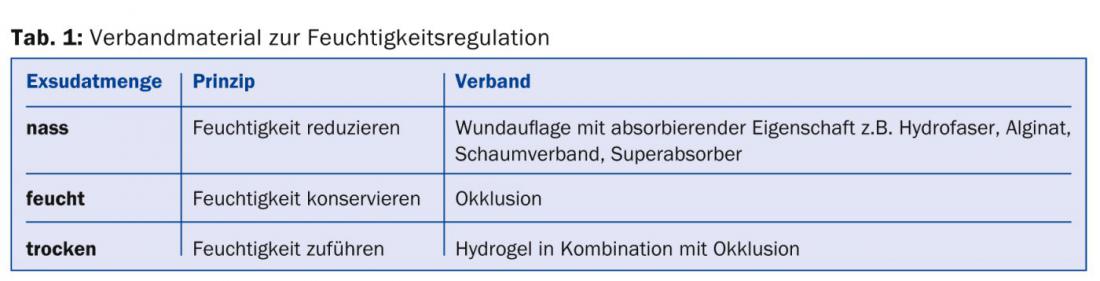

The goal of wound treatment is wound healing. It includes the treatment of causative, (e.g. pressure, friction, etc.) or healing-inhibiting factors of a wound such as infections, an unfavorable moisture environment (Tab. 1), necrosis, zinc deficiency, malnutrition, etc. and local wound treatment.

Healing of superficial wounds (e.g., blisters and abrasions) occurs through regeneration of the epidermis and leaves no scar tissue. Wound covering is usually only necessary for a short period of time.

Wound management of secondary healing wounds (acute and chronic wounds) is more complex. The treatment must be adapted to the respective wound healing phase (Tab. 2) .

The TIME concept (Tab. 3) shows general measures within the framework of wound bed preparation that optimize wound healing.

Primary wound care in general

Acute traumatic wounds are usually managed in the following steps:

- Analgesia (Tab. 4 and 5)

- Wound cleansing and disinfection (Tab. 6)

- Hemostasis

- Exploration

- Debridement of avital tissue

- Wound closure

- Wound dressing

Analgesia

Pain relief is especially important in childhood and should be provided early. Whenever possible, local analgesics are preferable to systemic ones. In addition to medication, distracting the child through play is often very helpful. Occasionally, however, analgesia must be supplemented with sedation for wound care.

Local analgesics

In addition to classic infiltration anesthesia (tab. 5 ) gels (LET gel, active ingredients: lidocaine, epinephrine, tetracaine) are now also available, with which sufficient anesthesia can often be achieved in superficial wounds by topical application, so that puncture is no longer necessary or is significantly less painful. Due to the epinephrine component, it must not be used in the area of the acras. The exposure time is at least 20 minutes. Based on the skin discoloration due to vasoconstriction, the superficial effect can be estimated.

Yarn material

The suture material must be adapted to the age and the wound situation. If the focus is on the stability of the seam, a stronger thread is used. If the focus is on aesthetics, a finer thread can be used (Tab. 7).

Monofilament, non-absorbable sutures are well suited for suturing acute wounds. Braided absorbable sutures are used in the mucosal and subcutaneous wound area and do not need to be removed. If the risk of infection is high, braided sutures should not be used, as their wicking action may draw germs into the wound. Absorbable sutures trigger an inflammatory reaction during their absorption, which may be noticeable by a circumscribed redness and must not be confused with an infection.

Wound closure

Most wounds are sutured, but in special situations they may be treated with staplers. For superficial wounds without major tension, bleeding and risk of infection, wound closure with skin adhesives is also possible. Infected wounds, or wounds with a high risk of infection due to wound cavities, contused tissue or underlying hematomas, should not be closed completely. If this is necessary, a drain should be inserted initially. Depending on the size of the wound, a wound drain or a small plastic flap can be used.

Wound dressing

In pediatric wound treatment, primary healing wounds with adapted wound edges as well as small petty wounds are dressed dry. Modern wound dressings or moist wound dressings are used for wounds with secondary healing. A dressing consists of either a primary dressing alone or in combination with a secondary dressing. The primary dressing is in direct contact with the wound. The secondary dressing is used for additional exudate absorption and/or fixation of the primary dressing. When applying the dressing, ensure that the primary dressing is always in contact with the wound bed. For wounds below skin level or wound cavities +/- pocket formation, wound fillers (e.g. wound gel, hydrofiber, alginate) are used for this purpose. The wound fillers are placed loosely in the wound cavity.

Tetanus protection

All potentially contaminated wounds must be considered for tetanus protection and, if necessary, a booster dose administered within 24 hours of trauma.

Details can be found in the current Swiss Vaccination Plan from the Federal Office of Public Health at www.bag.admin.ch (Tab. 8).

Thread removal

Suture removal is also performed, as is the selection of suture material, taking into account age, wound stability and aesthetics (Table 9).

Seam care

Showering and bathing: Showering is possible for dry wounds from the third day after wound care. Bathing is usually recommended only after thread removal.

Tension relief: Staple plasters and adhesive fleece can be used to take tension off the suture and thus promote wound healing in the first one to two months.

Sun protection: The scar should be protected from UV radiation for six to twelve months, by means of textiles (e.g. functional sun protective clothing, bandage) or repeated applications of a high protection factor sunscreen. Exposure to the sun too early may cause a change in the color of the scar.

Moisture: Since scar tissue contains less moisture than normal skin and therefore has a tendency to dry out, an unparfumed, lipid-replenishing ointment or cream should be applied regularly (approx. two to three times/day) until wound healing is complete.

Massage: Massage is performed as a hypertrophy prophylaxis. During the first days after thread or staple removal, the cream/ointment should only be massaged in gently. After three weeks, the massage can be intensified. Massage principle: Approx. twice a day. the tissue is carefully pushed against each other across the scar with light pressure, this allows the scar tissue to be detached from the underlying tissue layer.

Compression: Local pressure on the wound can reduce hypertrophic scarring somewhat. This is used, for example, in burn surgery with compression suits. These custom-made suits must be worn during wound healing until the completion of the maturation phase (usually over one to two years).

The positive effect can be further enhanced by additional silicone wound dressings under the suit.

Special wounds

In addition to the general principles of wound care, there are some special features to consider for the different types of wounds.

Lacerated and crushed wounds: In these wounds, severely crushed tissue should already be debrided during initial wound care so that primary wound healing is subsequently possible. Wound exploration often reveals wound pockets caused by shear forces in the area close to the wound margin. If there is an increased risk of infection and possible postoperative bleeding, a wound drain should be inserted (Fig. 1).

Cut/stab wound: Cut wounds through glass, in particular, often cause deeper soft tissue lesions than would be expected from external inspection. They must always be carefully explored to ensure that no foreign bodies remain in the wound and that tendon and nerve injuries are not overlooked. In young children, this exploration and wound care is often only possible under anesthesia. Precise clinical examination and documentation of peripheral motor function, sensitivity and perfusion is essential before local anesthesia is administered or anesthesia is induced and before a tourniquet is applied.

Bite wound: These wounds have a greatly increased risk of infection due to the germs and enzymes in the saliva of animals or humans. Therefore, bite wounds must be well cleaned, disinfected and, if necessary, the wound edges must also be excised. Complete primary wound closure should only be performed if this is necessary for esthetic and functional reasons (e.g., in the face). In this case, fine drainage flaps should then be inserted to allow secretion to escape and wound irrigation (e.g. with venous cannula without needle or button probe) to remain possible for the first two to three days.

Antibiotics should be given prophylactically (Table 10).

Abrasion: Surface friction usually ablates epidermal skin layers, and less frequently deeper dermal skin layers. These wounds can be very painful depending on the size and depth of the wound. Epidermal abrasions heal quickly and without scarring. In this case, a dressing that does not stick to the wound, allows moist wound healing and protects the wound from germs, e.g. a grease gauze dressing, is usually sufficient. Dermal abrasions, like thermal wounds, can leave grade IIb scars and require more intensive therapy. Wound care can be provided by burn surgery.

Decollement/Deglovement: Tissue contusion and shear forces (e.g., rollover trauma, wheel spoke injuries, ring injuries) can cause deeper injuries that are not externally apparent at first glance. These wounds are often costly to treat because the devascularized upper tissue layers can become necrotic and deeper sensitive structures are exposed after debridement, sometimes requiring extensive plastic surgery to cover the defect (Fig. 2a and b).

Pin entry sites: Percutaneously inserted Kirschner wires and external fixators are frequently used in pediatric fracture treatment (Fig. 3) . Infections rarely occur here. Wound checks and good pin care, if needed, can significantly reduce the risk.

Routine maintenance of the entry points is not necessary. In the case of crib wires, only a check of the wound area and a covering dressing to protect against dust and foreign bodies should be applied. In the plaster, the wire ends are also protected from external effects and cannot dislocate accidentally.

If there are signs of infection (painful, reddened, weeping entry sites), disinfection with an antiseptic is necessary after wound cleansing. A new cotton swab must be taken for each pin site. At home, non-sterile cotton swabs are sufficient.

In the case of closed wire entry sites, patients are also allowed to shower from the tenth postoperative day.

Scald/burn: Scalds, usually with hot drinks, occur more frequently than burns. In wound treatment, the area and depth of tissue damage is critical (Fig. 4a-d).

In most cases, it is not possible to decide between superficial and deep second-degree damage until about the fifth day. Superficial grade IIa wounds with intact basal cell layer epithelialize rapidly and heal without scarring. In this phase, fat-containing care products help to protect the fragile epidermis. Deeper skin damage in the sense of a grade IIb lesion and higher cannot regenerate from the depth and must be necrosectomized in the course and covered with split skin or full thickness skin. Initially, thermal injuries usually secrete heavily, so the dressing must absorb this fluid. It is also said to provide protection against infections. The material should allow for a painless and infrequent change. Exemplary dressing structure: silicone spacer grid as wound dressing and polihexidine-soaked longuettes, dry longuettes, cruff bandage and mesh dressing. Alternatively, foam dressings and creams (e.g. Ialugen Plus cream) can be used. Modern wound products for temporary skin replacement, such as Suprathel®, have the advantage that dressing changes are less painful and the wound dressing can be left in place.

Andreas Bartenstein, MD

Brigitte Wenger Lanz

Franziska Zwahlen-Müller

Literature:

- Dietz HG, et al: Practice of child and adolescent traumatology. Springer-Verlag 2011.

- AWMF: Guideline of the German Society for Pediatric Surgery – Wounds and Wound Treatment. 2011.

- La Scala G, et al: The treatment of wounds in the child. Paediatrica 2003; 14(4): 38-43.

- Streit M: Wound treatment in children. Pediatrics 2011; 10-16.

- Falanga V: The chronic wound: impaired healing and solutions in the context fo wound bed prepration. Blood Cells, Molecules and Diseases 2004; 32(1): 88-94.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

Wound management in the child:

- takes into account the types of wounds typical of old age and their specific complications.

- pays special attention to pain and anxiety and tries to reduce them to a minimum.

- must also adapt to the activity of the child in the dressing technique.

- often achieves very good results due to its very good tissue regeneration capacity.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(8): 28-35