Opiates are also appropriate for the very elderly. Renal function and compliance determine the selection of appropriate agents. Opiate therapy is initiated with very small doses. Side effects of opioid therapy, such as constipation and nausea, are co-treated from the beginning.

The age at which the last phase of life – characterized by often several incurable, chronically progressing diseases – is experienced is shifting further and further back, mainly thanks to the achievements of medicine. Dying and death are increasingly becoming a phenomenon of the very old. In the last months of life, pain is one of the symptoms that suffer the most, regardless of the main diagnosis [1].

With a good pain therapy, which takes into account the particularities of the old organism, much can be contributed to an improved quality of life in the last phase of life.

Multimorbidity

The elderly patient is typically characterized by his multimorbidity. It represents a challenge for pain therapy because, on the one hand, several causes of pain often exist simultaneously and overlap, and, on the other hand, the various diagnoses have a decisive influence on the choice of analgesics.

Multimorbidity leads to polypharmacy with high interaction potential, which must be kept in mind. And the declining organ functions lead to altered pharmacokinetics and metabolism, which should be considered when choosing analgesics [2].

Compliance

As age increases, so does the prevalence of functional limitations. This makes pain assessment and compliance particularly challenging.

Cognitive deficits, visual impairments, sensitivity problems, and fine motor limitations make it difficult to implement prescribed pain management.

Many very elderly people are overwhelmed with handling a prescribed medication regimen. Pushing a tablet out of the blister or opening a dropper bottle with a child safety lock can become an insurmountable challenge!

The prescribing physician must therefore ensure that the patient can implement the therapy at home.

Goals of pain therapy

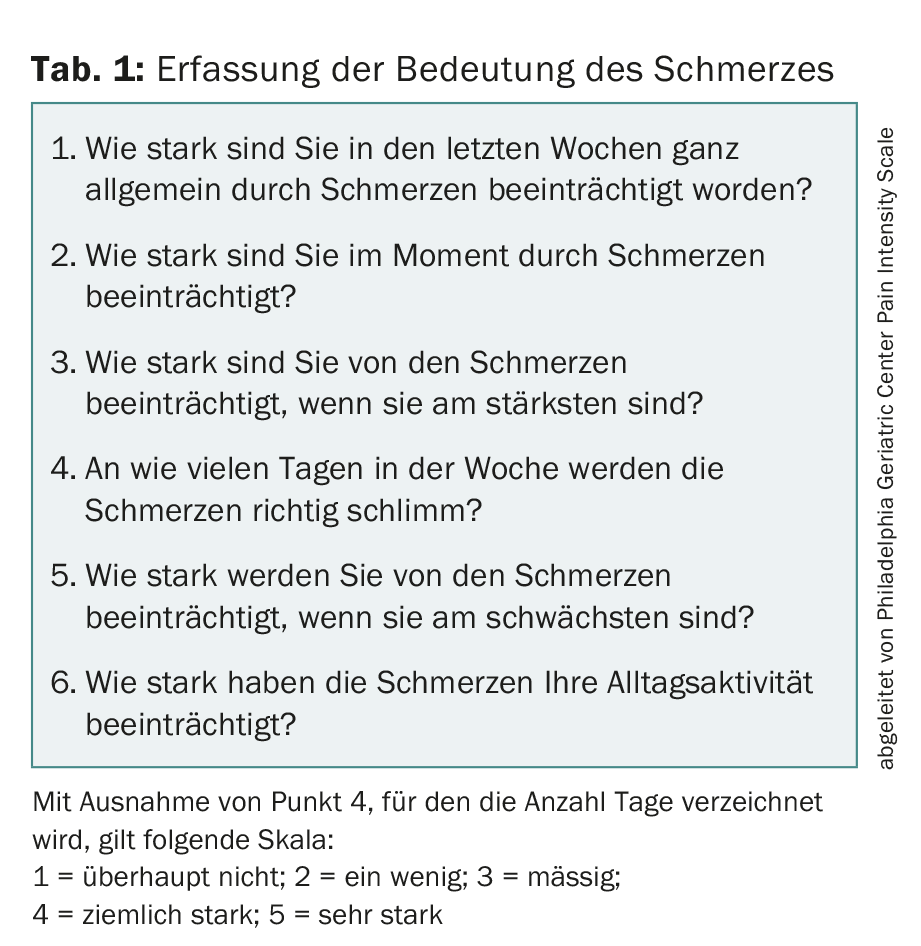

In the very elderly, multimorbid patient, achieving absolute freedom from pain can rarely be the goal, as too many causal factors are involved. Pain assessment with the visual analog scale (VAS) originates from postoperative pain management and does not adequately address the situation of the elderly. It is much more important to assess the impact of the pain problem on everyday functions (Tab. 1) and quality of life and to define the goals together with the patient accordingly. Freedom from pain at rest and in major activities of daily living is a realistic goal; at the same time, other previous activities may need to be limited or adapted [3].

Basic information on pain therapy

The correct pain therapy for the elderly does not exist, there is only the optimized individual analgesic therapy that takes into account the causes of pain, concomitant diseases, life situation, functional abilities, individual reaction patterns and personal needs of the patient.

The first step is to analyze the pain in terms of causally treatable causes and mechanism of origin. Another important question concerns the duration of the pain: acute pain is a warning signal and must be clarified in parallel with the initiation of therapy; chronic pain requires the definition of a realistic therapy goal. Before initiating pain therapy, concomitant diseases that affect metabolism and tolerance must be assessed. Limitations of kidney and liver function, cachexia, and swallowing problems are especially important to consider. After analyzing the overall situation and the previous therapy, the choice of the appropriate analgesic follows: primarily, a non-opioid is used; if the effect is insufficient, a switch to an opioid is made.

Non-opioid

Paracetamol is the first-line drug of choice. To date, its mechanism of action is only partially explained; primarily, the effect is likely to result from COX-2 inhibition. The dose-response curve is flat: increasing the dose above 2 g per day produces little additional effect but increased COX-1 inhibition and thus an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and probably heart failure [4]. Additionally, if there is pre-existing liver damage, liver toxicity should be considered. In anticoagulated patients, the INR may increase. The large tablets can be difficult for elderly people to swallow.

Metamizole is similarly potent as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for acute pain and has an additional spasmolytic component. It shows no gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, or renal side effects, but is associated with the rare risk of agranulocytosis. This risk is highest in the first weeks of therapy and decreases with increasing therapy duration. For chronic pain in the elderly, metamizole is a reasonable choice and is associated with significantly fewer side effects than NSAIDs. The daily dosage should not exceed 3 g divided into three to four individual doses when the patient is old. The available drop form facilitates the intake.

NSAIDs have analgesic and antiphlogistic effects by inhibiting COX-2. They should be used in elderly patients at most for acute inflammation-related pain, for a limited time, and not at maximum dosage. They are not suitable for chronic degenerative pain because of the high potential for side effects. Upper gastrointestinal side effects can be halved to the level of coxibe with the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI). However, the risk of lower intestinal tract bleeding, i.e., approximately one in five bleeds under NSAIDs, is not reduced by PPIs. A combination of NSAIDs with anticoagulants and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) or clopidogrel should be avoided in any case because of the risk of bleeding. The cardiovascular toxicity of NSAIDs is generally underestimated; except for naproxen, all cause clustered myocardial infarctions. NSAIDs and coxibs cause water and salt retention, so they should be discontinued when GFR is less than 60 ml/min because of the risk of cardiac decompensation and worsening renal function [5].

Opioids

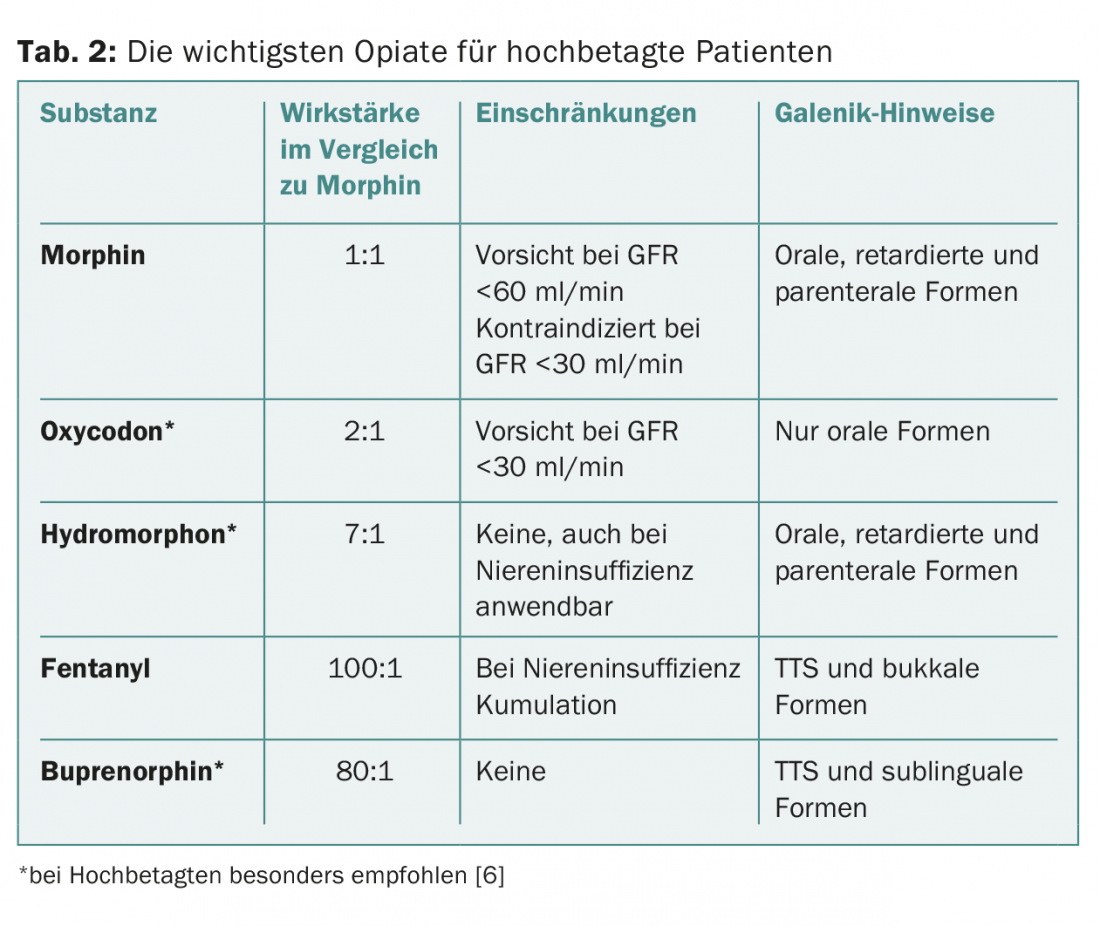

The principle of using weak opioids first and strong opioids only when the effect is insufficient is now considered outdated because the weak opioids such as codeine and tramadol have pharmacological disadvantages. In particular, the numerous interactions should be noted. A low-dose, level 3 opioid is therefore the more reasonable option for opioid initiation. The basic principle is “start low, go slow”: the initial dosage in the elderly should be reduced to half the dosage in younger people. There are negative and positive facts to consider when using opioids in elderly patients. On the one hand, the risk of falls is increased fivefold in the first four weeks after starting therapy, but it decreases again with longer use. On the other hand, long-term opioid therapy was shown to positively affect cognition, daily functioning, psychological state, and social factors in nursing home residents. Not all strong opioids are equally well suited for very elderly patients, as the following explanations show (Table 2) [6].

Morphine remains the standard opioid: available in various galenic forms, comparatively inexpensive, long experience. Limitations for use in very elderly patients include active metabolites that accumulate in renal insufficiency and lead to CNS side effects. Caution should be exercised with a GFR below 60 ml/min, and morphine should be discontinued below 30 ml/min.

Oxycodone alone or in combination with naloxone (to control opioid-induced constipation) is well tolerated by the elderly and is comparable in effect to morphine. Caution should be exercised in renal impairment; active metabolites may accumulate and naloxone may become systemically available.

Tapentadol is a medium-strength opioid that also acts as a norepinephrine uptake inhibitor, thus developing the analgesic effect with a lower opioid dose. Data are lacking for very elderly patients; in renal insufficiency, active metabolites may accumulate and possibly lead to seizures.

Hydromorphone is a potent opioid that is significantly more potent than morphine with the same tolerability and is available in all necessary galenic forms. It has practically no interaction potential and no active metabolites; in renal insufficiency, only the duration of action is prolonged. It is the ideal opioid for geriatric and multimorbid patients.

Fentanyl is used primarily as a transdermal system (TTS) and as a buccal form. In the elderly, there are uncertainties regarding absorption of the highly lipophilic substance in skin atrophy and cachexia.

Half-life is prolonged in the elderly and accumulation may occur in renal insufficiency, requiring dose adjustment.

Buprenorphine (available as TTS and sublingual forms) is only a partial agonist at the opioid receptor. However, this has no limiting effect clinically and makes the substance very well tolerated even in old age. It also works very well at higher doses, and the ceiling effect postulated in vitro remains insignificant in clinical practice. Metabolism occurs almost exclusively via the liver, thus buprenorphine can also be used in renal insufficiency. In addition, the substance seems to work better than other opioids on neuropathic pain.

Data on other opioids for use in very old patients are lacking, so they are not discussed here.

Combinations and co-analgesics

The often recommended combination of opioids with acetaminophen shows only questionable benefit, the evidence is low, and in the multimorbid patient with polypharmacy it is more likely to add risk. For neuropathic pain, complementary medication with co-analgesics to opioids is recommended.

In the very elderly patient, however, both the well-documented tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline and the anticonvulsants such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and lamotrigine are not recommended or should be used with extreme caution because of their potential for side effects (high risk for CNS side effects such as confusion).

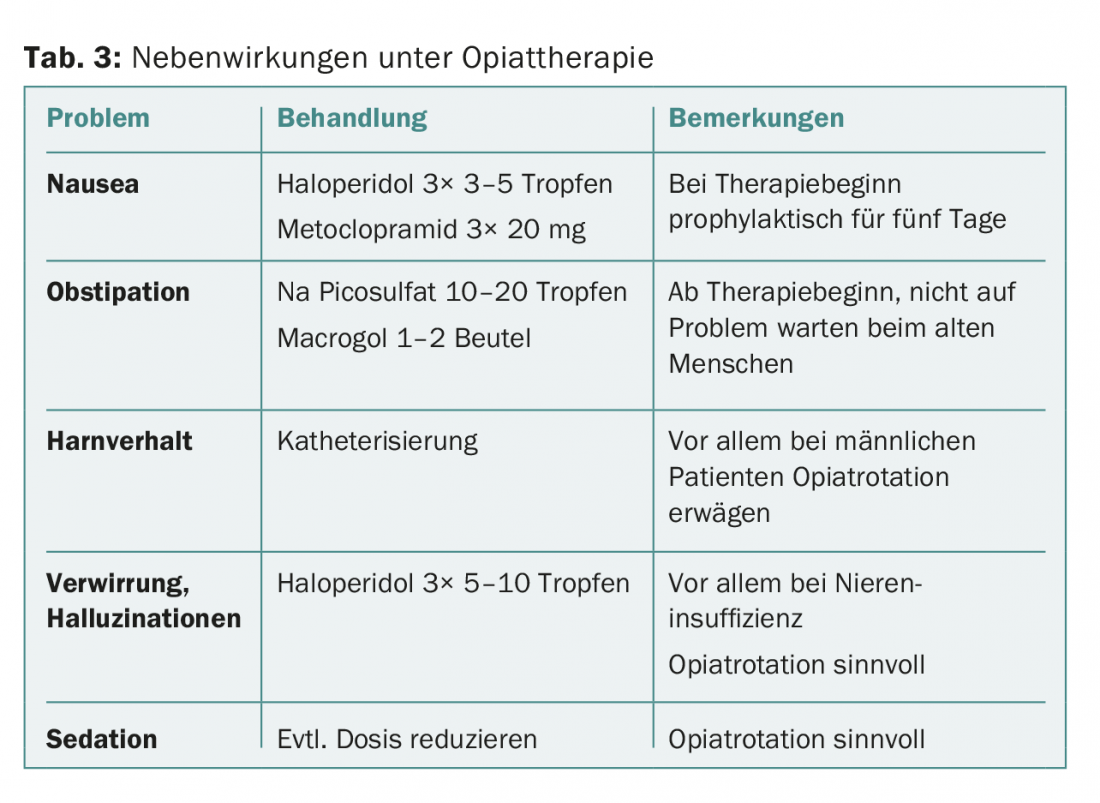

Side effects of opioids

The obligatory side effects of opioids must be particularly observed and anticipated in the elderly patient (tab. 3) . In the first days of therapy, prophylactic treatment of nausea with metoclopramide or haloperidol is useful; after about five days, it can be discontinued. Constipation should also be treated from the beginning. Opioid-induced urinary retention occurs more frequently in old age and should be recognized in a timely manner [7].

Literature:

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS: Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(8): 747-755.

- Wooten JM: Pharmacotherapy Considerations in Elderly Adults. South Med J 2012; 105(8): 437-445.

- Kunz R: Pain: commonplace yet a complex challenge. PrimaryCare 2014; 14(19): 311-313.

- Liechti ME: Pharmacology of analgesics for practice – Part 1: Paracetamol, NSAIDs and metamizole. Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14(22-23): 437-440.

- Gosch M: Analgesics in the geriatric patient – adverse drug reactions and interactions. Z Gerontol Geriat 2015; 48: 483-493.

- Pergolizzi J, et al: Opioids and the Management of Chronic Severe Pain in the Elderly: Consensus Statement of an International Expert Panel with Focus on the Six Clinically Most Often Used World Health Organization step III Opioids (Buprenorphine, Fentanyl, Hydromorphone, Methadone, Morphine, Oxycodone). Pain Practice 2008; 8: 287-313.

- Caraceni A, et al: Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 58-68.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(2): 30-33.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(8): 16-19