Traditionally, infectious urethritis is divided into two groups: Gonococcal urethritis (GU) and so-called non-gonorrheic urethritis (NGU). This classification arose historically to distinguish NGU-a group of infections of similar symptomatology with, at the time, an unclear, heterogeneous, and difficult-to-determine etiology-from the much better-studied and more serious, gonorrheic urethritis. NGU, formerly also called nonspecific urethritis, was comparatively rare along with gonorrhea but now far exceeds its incidence. The following article discusses NGU, its pathogen spectrum, the necessary clarification steps and therapeutic measures.

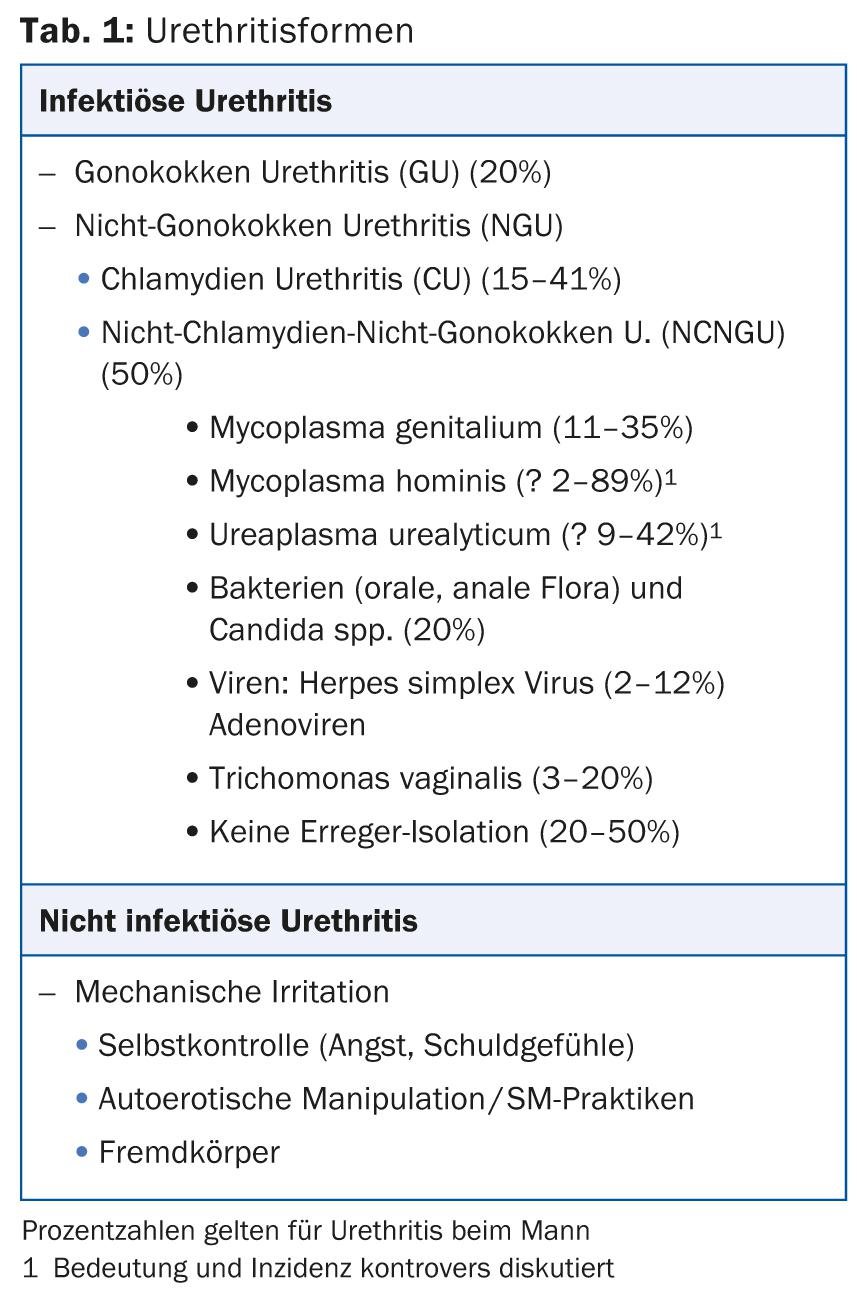

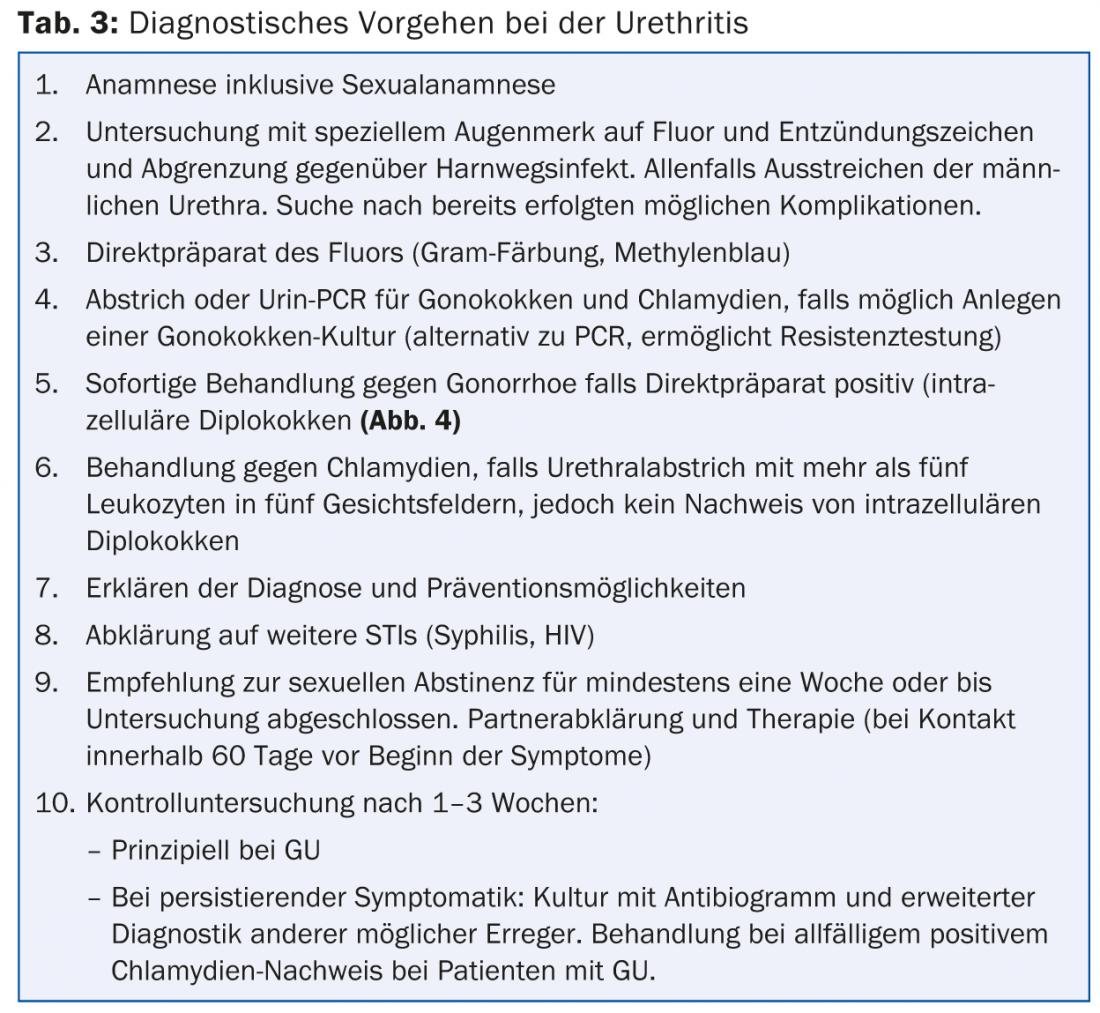

In principle, when diagnosing urethritis, a urinary tract infection must primarily be excluded, which may occasionally offer differential diagnostic difficulties. When urethritis presents with the typical clinic of alguria and fluoride with >5 Leukocytes in five visual fields (or >10 leukocytes in five visual fields in first-stream urine) is confirmed, a distinction must be made between a non-infectious and an infectious form (table 1). Typical causes of non-infectious urethritides are mechanical-traumatic triggers such as the insertion of foreign bodies, excessive sexual intercourse, certain S&M practices, and recurrent stripping of the penis for self-control in fluorine. Also, chemical (e.g., disinfectants, soaps) or local causes such as congenital anomalies, phimosis, and neoplasia may be accompanied by noninfectious urethritis. However, only infectious urethritis will be discussed below.

Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis comprises a total of 15 serotypes defined by different protein antigens, designated by the letters A-C, D-K, and L1-L3, which cause different diseases.

C. trachomatis is found in 15-41% of all urethritis cases in men. However, in the literature of the last decade, the frequency of chlamydia as a causative agent is not consistently reported. In Switzerland, a prevalence of 3-4% can be assumed in women between the ages of 16 and 30. Transmission occurs during sexually unprotected contact, with age under 20 years, promiscuity, and lack of or improper condom use as risk factors. Annual screening for sexually active patients younger than 25 years is recommended as well as for women older than 25 years with risk factors (multiple partners, new partners).

Chlamydia infection in men becomes noticeable after an incubation period of seven days to three weeks with serous discharge. Additionally, burning sensation and alguria are indicated. The examination usually reveals no findings other than a discrete redness of the orificium urethrae and adhesions of the urethral orifice. In 30-50% of all infected men, the infection is asymptomatic. The most common site of chlamydial infection in women is the cervix, and the infection is asymptomatic in up to 70%. The clinically manifestations are whitish-yellowish genital discharge with itching and burning at the vaginal introitus.

Diagnosis: In women, the pathogens are detected by smear tests of the cervix or vagina or urine analyses (somewhat less sensitive) using PCR. In men, a urine examination or a smear from the urethra may also be performed.

Due to their small size and low affinity for dyes, chlamydiae cannot be seen natively or by staining. As obligate intracellular bacteria, cultivation is also difficult.

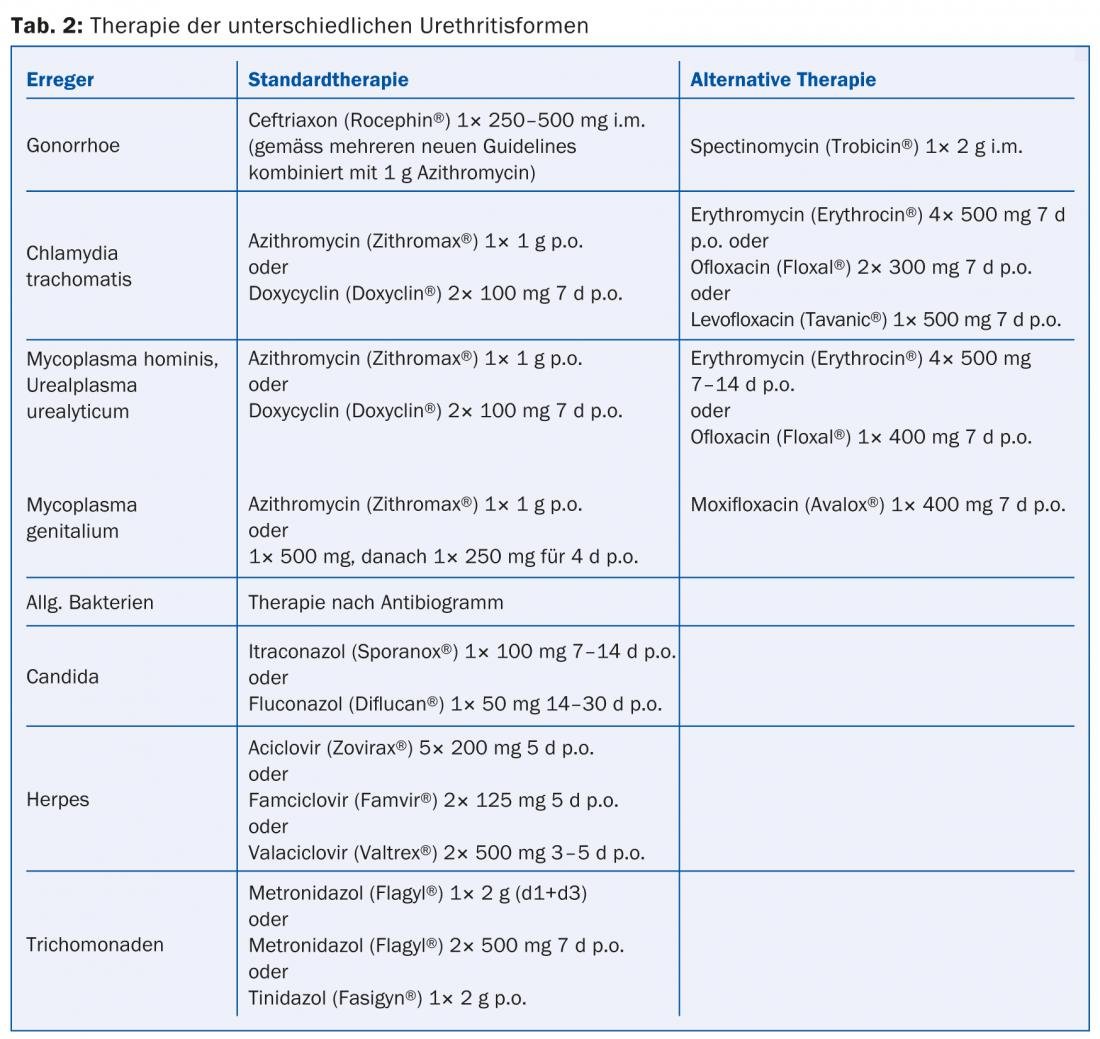

Therapy: uncomplicated, urogenital infections can be treated with doxycycline 2×100 mg for seven days or azithromycin 1 g once. The efficacy of the two antibiotics is nearly equivalent with slightly better response to doxycycline but the better compliance of azithromycin. As recently documented, healing rates appear to be somewhat declining under these standard therapies. Based on current data, azithromycin, like erythromycin, can be considered safe in pregnancy. Alternatively, amoxycillin 3×500 mg/d for seven days may be administered during pregnancy.

Mycoplasma

Mycoplasmas are immobile gram-negative bacteria. They differ from other bacteria in their small cell size, small genome, and lack of cell wall. On special culture media, ureaplasmas (Ureaplasma urealyticum) and non-ureaplasma mycoplasmas (Mycoplasma hominis) can be distinguished.

The significance of genital mycoplasmas for the development of sexually transmitted diseases is controversial. M. hominis does not appear to be responsible for NGU in males, despite detection in the genitourinary tract. Likewise, U. urealyticum can often be isolated from the genital tract of healthy women and men, but possible clinical manifestations have been postulated at high bacterial concentrations, with the specific serotype biovar 2, and with initial infection. However, the pathogenic potential has been documented several times for M. genitalium. Mycoplasma infections can cause clinical symptoms of urethritis in men in addition to silent courses. In particular, U. urealyticum and M. genitalium infections manifest themselves in the form of acute, but also chronic urethritis with dysuria and fluoride. Although there are limited data to date on the significance of M. genitalium infections in women, individual study results do suggest a strong association of M. genitalium with cervicitis, acute endometritis, genital ulcers and possibly upper genital tract infection (PGD).

Diagnostics: Due to their size and low affinity for dyes, detection of mycoplasmas in Gram preparations is not possible. U. urealyticum and M. hominis are detected by culture (or PCR), M. genitalium by PCR. Serological tests are of no importance for the diagnosis of infections with mycoplasmas in clinical routine.

Therapy: Tetracyclines, macrolide antibiotics and quinolones are the drugs of choice. Doxycycline 2×100 mg/d for seven days or azithromycin 1× 1 g are considered standard therapy for M. hominis and U. urealyticum (Table 2). For chronic forms of urethritis, a longer duration of therapy may be necessary. Azithromycin is recommended for the treatment of M. genitalium urethritis because it is clearly superior to tetracyclines in efficacy. Increasingly, treatment failures have been observed recently, which is why a multi-day treatment (1×500 mg on the first day, followed by 1×250 mg on four days) is favored in case of non-response to 1 g azithromycin (Table 2). Moxifoxacin is considered the absolute reserve drug.

Bacteria of the oral and anal flora

Urethritides can be caused by numerous other bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus can result in urethritis, cystitis, or prostatitis, especially in patients with urethral catheters. Streptococci and especially enterococci can also lead to urethritis. E. coli can rarely cause urethritis, cystitis, prostatitis or epididymitis, and pyelonephritis in men after anal intercourse.

Pathogens of the oral flora such as Haemophilus influenzae may not infrequently be causally responsible, especially since oral sex is nowadays regarded by many as supposedly unproblematic with regard to the transmission of infections and consequently few condoms are used during oral sex.

Diagnosis: Bacteriological detection of the pathogen by means of culture should always be sought to establish the diagnosis.

Therapy: Therapy depends on the pathogen and antibiogram.

Candida

Candida albicans can lead to urethritis secondary to balanitis or vulvovaginitis, especially in the presence of diabetes mellitus or immunodeficiency.

Diagnosis: Detection is performed in the direct preparation and by mycological culture.

Therapy: Imidazole derivatives such as itraconazole 100 mg/d for 7-14 days or fluconazole 50 mg/d for 14-30 days are used for therapy (Table 2).

Viruses

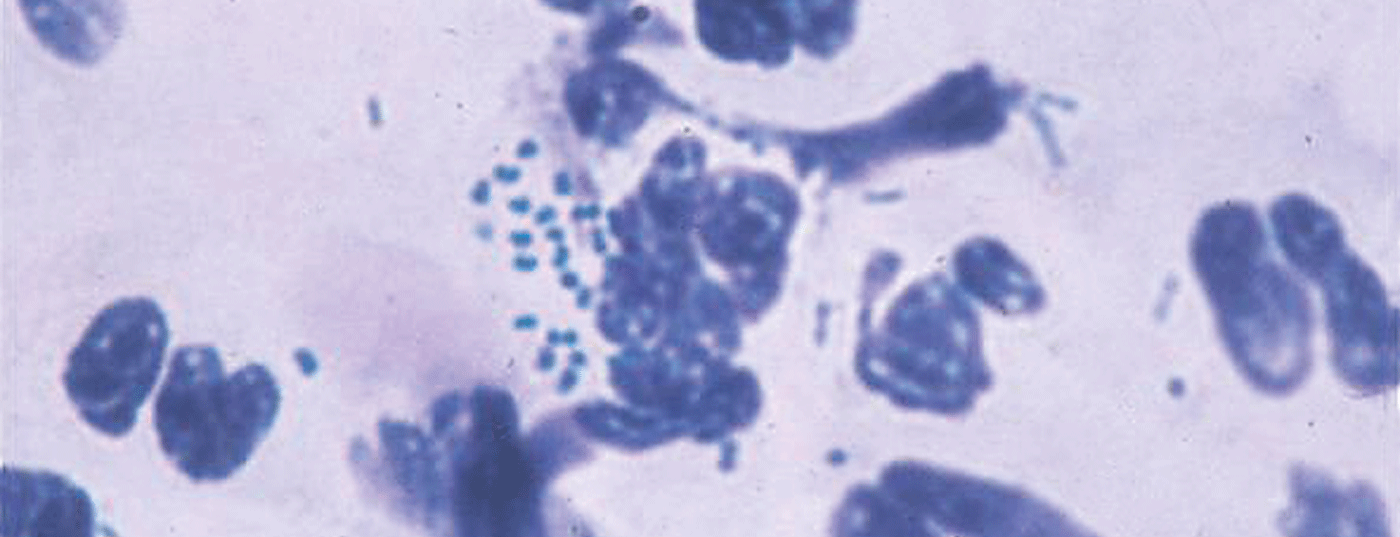

Viral urethritis must be suspected if the bacteriological clarifications were unproductive. In herpes urethritis, a painful serous discharge is found, often accompanied by herpetiform eruptions on the external genitals. Less commonly, exclusively intraurethral herpes simplex infection occurs. Recent studies have shown that herpes simplex type 1 (Fig. 1) causes NGU more frequently than herpes simplex type 2.

Adenoviruses can also cause urethritis. This is usually characterized by marked meatitis and pain (Fig. 2), and the majority are also accompanied by highly contagious conjunctivitis (Fig. 3) . Especially after unprotected oral contact, adeno- and herpes type 1 viruses must be considered as the cause in the absence of pathogen detection, especially in homosexuals.

Diagnostics: In the case of herpes infections, smear examination is a good option. Cultural detection of HSV requires approximately 48 hours. Viruses can only be obtained from fresh lesions for cultivation. By PCR, the smear material can be analyzed within a few hours. The culture like PCR can also be done from urine. Antigen detection by immunofluorescence is also suitable for diagnosis. Detection of adenoviruses can also be done from urine.

Therapy: Therapy of herpetic urethritis is performed with nucleoside analogues if required.

Trichomonads

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellate of oval shape with four flagella and an undulating membrane. Trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted infection that occurs worldwide and its prevalence depends on sexual risk behavior. In statistics, there are significant differences in infection rates between individual population groups and between developed and developing countries. The age peak corresponds to that of peak sexual activity and correlates with the presence of other STIs that should be excluded.

Transmission of T. vaginalis is mainly by sexual contact and only rarely by contamination, as survival time outside a moist environment is short. Women are affected more often than men. Symptoms may include vaginitis, prematurity, and premature rupture of membranes. About a quarter of infected women are asymptomatic. In men, trichomoniasis is poorly studied, but according to studies, it is thought to cause up to 20% of NGU cases in men in certain regions.

Diagnosis: The best diagnostic procedure is microscopic examination in native specimen with 0.9% NaCl from the vaginal vault, cervix and urethra. In women, about 75% of infections can be diagnosed this way. Polarization or dark-field microscopy increase the hit rate.

The smear is usually rich in neutrophils and mucosal epithelial cells, so flagellates are best identified by their movement. As a result of the lower detection rate in males, morning urine sediment testing may be required.

A number of suitable culture media with a sensitivity of about 95% are available. The culture is offered in very few laboratories. PCR is also not widely used. The serum antibody response to trichomonad infection is variable and unreliable, so routine serologic testing is not recommended.

Therapy: trichomoniasis can be treated with metronidazole 1× 2 g with possible repetition after two days or with 2×500 mg/d for seven days, but the antabuse-like effect should be noted. Furthermore, tinidazole 1× 2 g is a therapeutic option. Tinidazole has a longer half-life, fewer side effects, and a slightly higher cure rate.

Management

An example of a possible approach to urethritis is listed in Table 3.

Literature by the author

Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Lautenschlager

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2013; 23(6): 7-11