Of particular note is the update to the recommendations on the delivery of systemic therapy. Newly approved active ingredients were integrated, and there is also a special focus on the consideration of comorbidities and special treatment situations. Other updates include the concretization of the criteria for the use of biologics and “small molecules”, but practice-relevant adjustments were also made in other sections.

Moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris in particular can have serious effects on health-related quality of life. Fortunately, however, treatment options have improved greatly in recent years. Since the last guidelines were published, numerous new systemic therapeutic options have come to market and additional drug candidates are in the pipeline. Updating guidelines in a rapidly changing environment is a major challenge. On the occasion of this year’s virtual meeting of the German Dermatological Society (DDG), Prof. Alexander Nast, MD, Division of Evidence Based Medicine, Clinic for Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Charité- Universitätsmedizin Berlin, spoke about the new edition of the s2k guideline on the therapy of psoriasis vulgaris published in February 2021 [1,2].

Integration of new treatment options

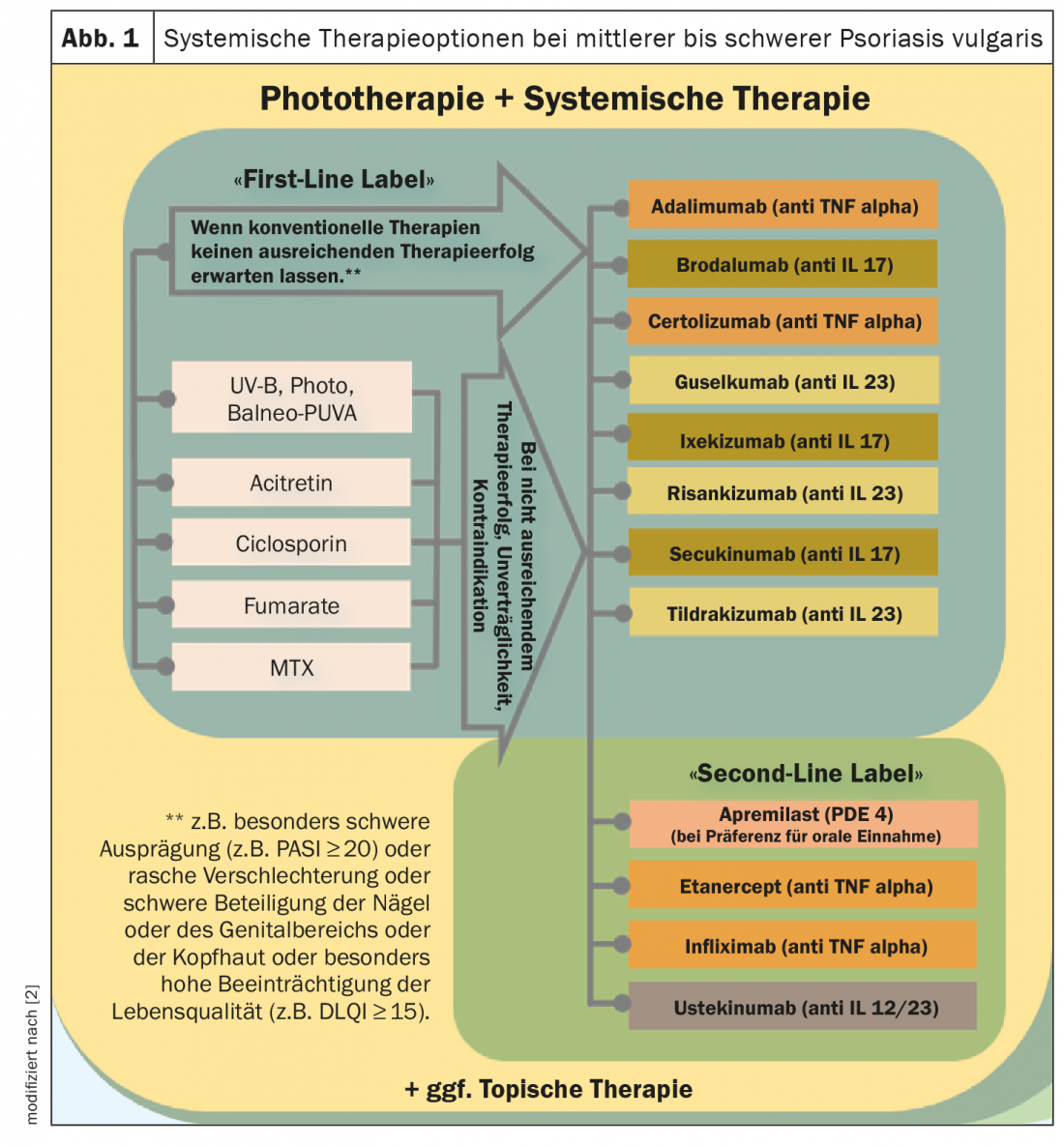

In light of the expanded spectrum of systemic agents and a continuously growing evidence base regarding efficacy and safety, the treatment recommendations for phototherapy/systemic therapy of moderate and severe psoriasis have been revised (Fig. 1) [1,2]. For example, the new biologics approved for this indication were included in the guideline and provided with appropriate references. The primary goal is to provide evidence-based decision support for the selection and implementation of appropriate therapy to reduce psoriasis-related morbidity and health-related quality of life impairments. Unchanged from the last version of the psoriasis guideline are the treatment recommendations for patients with mild psoriasis vulgaris. This also applies to the classification of psoriasis severity (mild psoriasis: BSA ≤10 and PASI ≤10 and DLQI ≤10; moderate to severe psoriasis: BSA >10 or PASI >10 and DLQI >10, respectively, according to the “upgrade criteria “*) [3].

* “Upgrade criteria”: classification as moderate to severe psoriasis if the following conditions are met: Pronounced disease of visible areas, pronounced disease of the scalp, disease of the genital area, disease of the palms and soles, onycholysis or onychodystrophy of at least two fingernails, itching and associated scratching, presence of therapy-resistant plaques.

Modified criteria for the use of biologics and small molecules

In order to make the guidelines easier to implement, the criteria justifying the use of drugs from the field of biologics and small molecules were specified and are currently as follows: “If conventional therapies are not expected to be sufficiently successful, for example in the case of particularly severe manifestations (e.g. PASI ≥20) or in the case of rapid deterioration or severe involvement of the nails or genital area or scalp or particularly high impairment of quality of life (e.g. DLQI ≥15)”. [2]. The basic goal of any therapy is freedom from manifestations, and the minimum therapeutic goal at the end of induction therapy is a PASI75 response. During the course of treatment, a review should be performed at regular intervals, for fast-acting drugs at the end of induction therapy after ten to twelve weeks, and for slow-acting drugs after 16 to 24 weeks. During maintenance therapy, the review usually takes place every eight to twelve weeks.

Comorbidities: stronger weighting

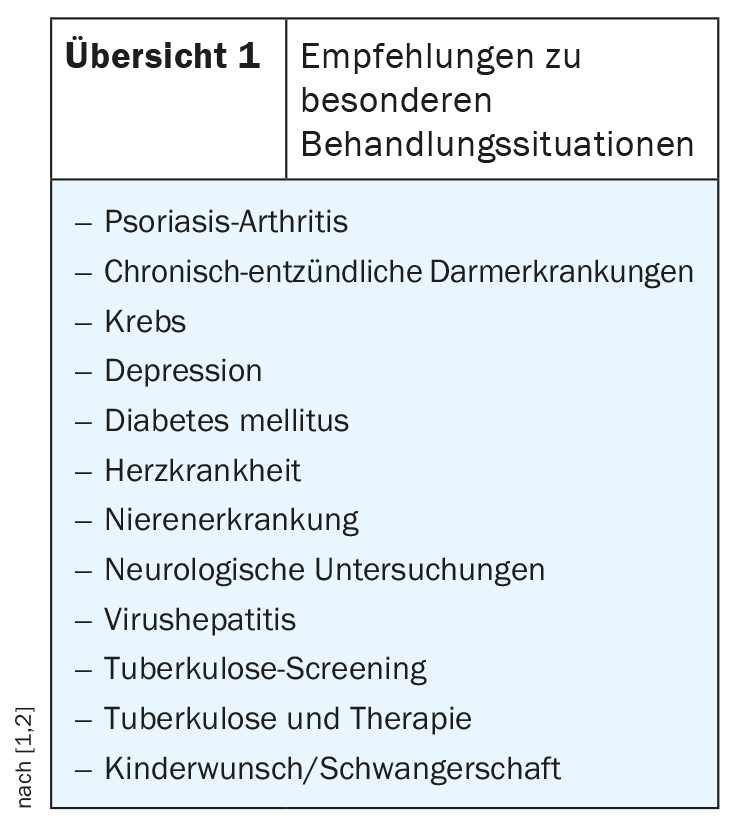

Subchapters were generated for frequent problem constellations such as the presence of psoriatic arthritis, depression or diabetes mellitus, in which specific treatment recommendations are made for these situations (overview 1) [2]. These are summarized in a presentation in the guidelines. In the field of psoriatic arthritis, a significant change worth mentioning is the equal positioning of IL17 antagonists compared to TNF-alpha antagonists. Of course, recommendations on necessary measures before, during and after treatment (e.g. vaccination, laboratory controls) as well as information on contraindications and drug interactions are again part of the guidelines. In the section “Tuberculosis (TB) Screening”, the omission of the tuberculosis skin test should be mentioned, and recommendations have also been added on how management should be carried out in cases of v.a. for latent TB.

Network meta-analysis as evidence base

The newly published guidelines were designed and implemented as part of the EuroGuiDerm Guideline Center, which has been located at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin since 2018, in cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum . In a first step, the European guidelines were updated, which serve as a basis for the adaptation of the national professional societies [4]. In order to pool resources in the preparation of evidence, a collaboration took place with the Cochrane Collaboration. In this context, among other things, a network meta-analysis was created [5]. This allows estimation of effect sizes for all pairwise comparisons of interventions, including those not previously compared head-to-head in randomized-controlled trials. The latter are also called indirect comparisons. “A network from which you can make constructed comparisons of efficacy and statistically generated assumptions about efficacy,” Prof. Nast explains. A conclusion of the Cochrane Review is that biologics from the substance classes of IL17 inhibitors and IL23 inhibitors have proven to be the best therapy options in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris in a placebo comparison with regard to PASI90 response [5]. The authors point out that the evidence on this is limited to the induction phase (8 to 24 weeks after randomization).

Outlook: What are the challenges ahead?

The authors of the Cochrane network meta-analysis point out that further randomized trials directly comparing different agents are needed in the future, including head-to-head studies among and between conventional systemic agents, small molecules, and biologics [5]. In the latter, comparisons between anti-IL17 vs. anti-IL23, anti-IL23 vs. anti-IL12/23, and anti-TNF-alpha vs. anti-IL12/23 would be of particular interest. Furthermore, systematic subgroup analyses should be performed in future studies regarding biologics-naïve patients, psoriasis severity at baseline, presence of psoriatic arthritis, etc.). Further challenges concern the harmonization of outcome parameters and the assessment of mid- and long-term efficacy and safety of the different agents. Finally, Prof. Nast points out that the guideline for the treatment of psoriasis in children and adolescents is currently being revised, with publication of the new edition planned for 2021 [6].

Congress: DDG Conference 2021

Literature:

- Nast A: New and old guiding(d) lines in PsO and AD, Prof. Alexander Nast, MD, S09: Track Inflammation: Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as systemic diseases. DDG Meeting 2021, 17.04.2021.

- Nast A, et al: German S3 guideline for the therapy of psoriasis vulgaris, adapted from EuroGuiDerm – Part 1: Therapy recommendations and monitoring. 2021. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges (in print).

- Mrowietz U, et al: Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011; 303: 1-10.

- Dressler C, et al: EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris – methods & evidence report, www.edf.one (last accessed 04/19/2021).

- Sbidian E, et al: Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 1. art. No.: CD011535, (last accessed 04/19/2021).

- AWMF S2k Guideline. Therapy of psoriasis in children and adolescents. AWMF Register No.: 013-094, 2018, www.awmf.org, (last accessed 04/19/2021).

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(3): 26-28 (published 5/31/21, ahead of print).