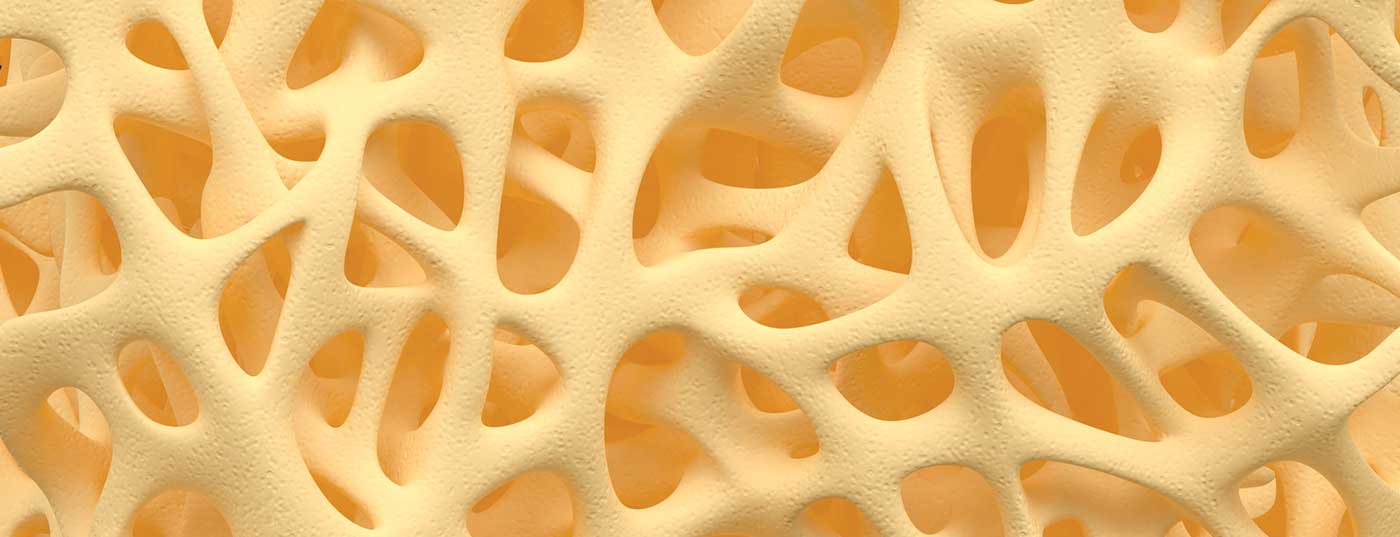

Osteoporosis is especially common in older patients. In order to reduce the risk of fractures, therapeutic long-term measures should be oriented to the patient and his individual needs.

Osteoporosis affects over 200 million people worldwide [1,2]. According to prevalence data from the EPOS study, there is an age-correlated increase from 15% (50-60 year olds) to 45% (in >70 year olds) in women [3]. In the context of demographic change and an increase in life expectancy, it can be assumed that the incidence and prevalence of these diseases will continue to increase [4].

Prevalence and burden of disease are significant

In the USA, approximately 30% of all postmenopausal women suffer from osteoporosis [4]. In Switzerland, one in two women over the age of 50 is at high risk of developing osteoporosis in their remaining lifetime [5]. During menopause, bone density decreases 3-5% per year, leading to an increased risk of fracture. Estrogen deficiency leads to accelerated bone metabolism, and declining estrogen levels reduce calcium absorption. In addition, the risk of vitamin D deficiency and an associated reduction in calcium absorption from the intestine and calcium incorporation into the bones increases. As 1-year prevalence data from the Swiss Health Interview Survey of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office show, already in the age group 45 years and older, the incidence increases significantly more in females than in males. In the 75+ cohort, the proportion is 2.5% for men and 20.6% for women; for 65-74 year olds, the proportion is 12.6% for women and 2.1% for men [1,2]. Osteoporosis fractures are distressing and can lead to a massive impairment of quality of life. After a hip fracture, the risk of needing long-term care is increased. As a result of a fracture, there may be fear of movement and associated loss of mobility. This can lead to depressive disorders. In addition, lack of exercise increases the risk of recurrence of fracture [5]. In individuals who have already had a fracture, the risk is increased by 86% [6]. In addition to genetic predisposition, gender and age, lifestyle factors such as immobility, underweight, smoking and alcohol consumption are among the most important risk factors for osteoporosis.

Combination pharmacotherapy and lifestyle measures is effective

Prophylaxis and therapy should be patient-oriented and adapted to personal conditions. Diagnostically, anamnesis, laboratory examination and bone density measurement by means of DXA (densitometry) are central. Regarding T-score as a result of bone densitometry, -1 to -2.5 is a precursor of osteoporosis and -2.5 and above is osteoporosis [5]. Follow-up is a very important factor and should be done by regular DXA/bone density measurements (every 2-3 years) after the start of therapy. Possible treatment goals are fracture-free intervals and a femoral T-score >-2.5 [7].

The recommendations regarding lifestyle measures according to SVGO are as follows [8]: sufficient calcium intake (1000 mg/day) and vitamin D supply (≥800 E/day, possibly vitamin D supplementation) as well as a balanced diet with sufficient protein intake (1 g/kg bw) and regular physical activity, fall prevention, and avoidance of risk factors (e.g., smoking, excessive alcohol consumption).

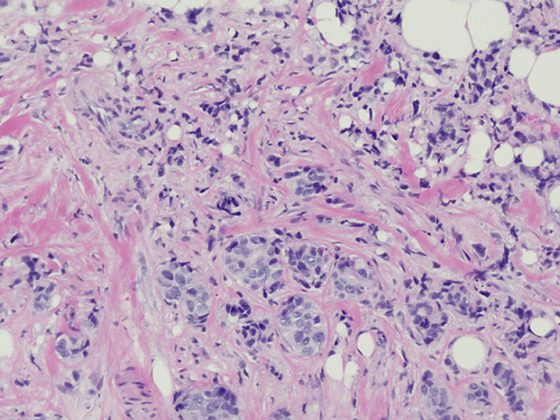

Biphosphonates as a therapeutic option

Antiresorptive agents, which include biphosphonates and denosumab, inhibit accelerated skeletal breakdown [5]. According to SVGO guidelines, bisphosphonates are among the most important pharmacological therapy options, along with denosumab, parathyroid hormone peptides, and raloxifene (an estrogen). That biphosphonates lead to a measurable increase in bone density and a reduced risk of fracture has been empirically demonstrated [9]. Binosto® is a biphosphonate preparation based on alendronic acid/alendronate and is available in the administration form of an effervescent tablet. The mechanism of action is that the active ingredient binds to the bone substance and is taken up by the bone resorption cells (osteoclasts) during bone resorption. Thus, cell metabolism is inhibited, which is why the osteoclasts can no longer work and die.

The duration of treatment with antiresorptive preparations depends on the patient and his individual fracture risk on the one hand and on the preparation on the other [8]. For patients with moderate fracture risk (max. 1-2 vertebral fractures before initiation of therapy; no incisional fractures or adequate BMD progression in follow-up DXA), a therapy duration of 3-5 years is recommended. For patients at high risk of fracture (multiple vertebral fractures before initiation of therapy; persistently low femoral neck bone density after 5 years of treatment, T-score ≤-2.5 SD), longer bisphosphonate therapy (5-8 years) is indicated. After discontinuation of the therapeutic agent, regular follow-up should be performed and a new cycle of therapy may need to be considered if bone mineral content values deteriorate or a new fracture occurs. An individual benefit-risk analysis should be performed. With regard to indications, contraindications and side effects, the currently valid technical information of the respective preparation is authoritative. Gastroesophageal intolerances are the main cause of therapy discontinuations under biphosphonates. Other side effects that may occur with antiresorptive therapy include associated osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fracture. A frequently observed problem in clinical practice is that the long-term risks of side effects are small, but patients’ perception of these risks is very high. In contrast, if treatment is too short, the risk of fracture remains elevated [8].

Literature:

- OBSAN (Swiss Health Observatory). www.obsan.admin.ch/de/indikatoren/osteoporose, last accessed June 27, 2019.

- FOPH (Swiss Federal Office of Public Health), www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home.html, last accessed June 27, 2019.

- Gourlay ML, et al: Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med 2012; 19; 366(3): 225-233.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation, www.iofbonehealth.org/epidemiology, last accessed June 27, 2019.

- brainMAG: Interview with Elisabeth Treuer Felder, MD, by Athena Tsatsamba Welsch. brainMAG Neurology Psychiatry Geriatrics 2019; 1: 37-40

- Kanis JA, et al: A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 2004; 35(2): 375-382.

- VZI Symposium 2019: Sigrid Jehle-Kunz, MD, Specialist in General Internal Medicine, Certified Osteologist (SVGO, DVO, ISCD), Head of OsteoporosisCenter Klinik St. Anna, www.zuercher-internisten.ch/symposiumsbeitraege-2019/16-osteoporose-ws.pdf

- SVGO (Swiss Association against Osteoporosis): Recommendations 2015. %20Empfehlungen%last accessed June 27, 2019.

- Russel RG: Bisphosphonates: the first 40 years. Bone 2011; 49: 2-19.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(7): 22-24