Patients with asthma can nowadays be treated well, even in severe forms, if they are given the individually appropriate treatment. Long-term use of oral corticosteroids (OCS) is problematic because of the associated risks and side effects. The use of biologics as adjunctive therapy is a useful strategy to reduce OCS and improve quality of life. In order to select the individually appropriate antibody therapy, determining the asthma phenotype is helpful.

Asthma and COPD are the most common obstructive airway diseases and play an important role in outpatient care. About 4-7% of the Swiss population suffers from asthma. Typical clinical manifestations are respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, thoracic tightness, cough as well as whistling and wheezing. Symptoms vary over time, depending on seasonality and viral infections, among other factors. Interdisciplinary management is required, especially in severe forms. On the occasion of the Davos Medical Congress, Prof. Dr. med. Jörg D. Leuppi, Chief of Medicine, Baselland Cantonal Hospital, gave an update on asthma therapy in the era of biologics [1]. About 5-10% of asthma sufferers have severe or difficult-to-treat asthma, which is usually treated in collaboration with a pulmonologist or allergist [2,3]. Severe asthma is when, despite optimal treatment adherence and maximal therapy with maximum-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus at least one other long-term medication and, if appropriate, the administration of oral steroids (OCS), there is unchanged poor lung function, frequent exacerbations requiring steroids or leading to hospitalization, and the criteria of partially controlled or uncontrolled asthma are present [1,4]. The risk of severe exacerbations is increased in patients with uncontrolled asthma, with concomitant risks of hospitalization and mortality. Approximately one-quarter of patients with severe asthma report four or more exacerbations annually [12].

Level of eosinophilia correlates with asthma outcome

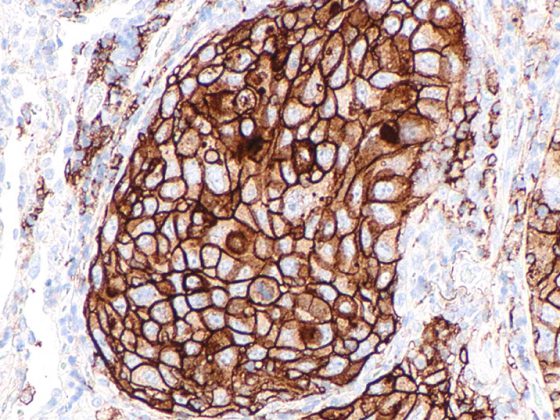

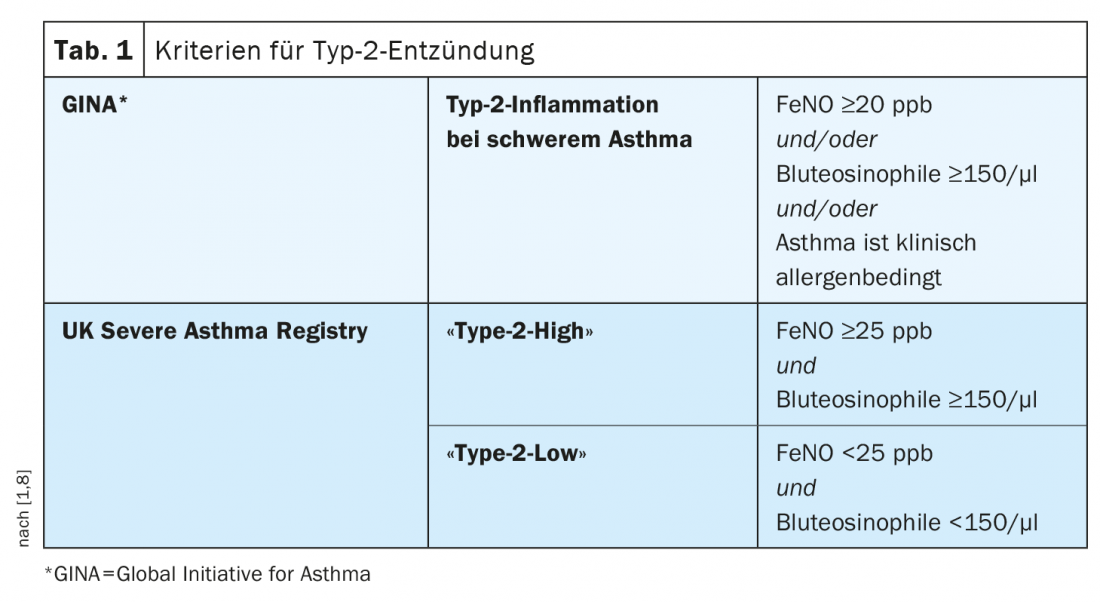

Severe asthma includes various phenotypes, which differ in terms of clinical manifestations, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and treatment response [5]. The two most common clinical phenotypes are characterized by eosinophilic inflammation and are termed primary allergic “early-onset” and eosinophilic “adult-onset” asthma, respectively. The complex pathophysiology is dominated by a Th2 immune response (Table 1) [1,6,8]. “Adjusted for other co-factors, the level of eosinophilia is a risk factor for increased exacerbation frequency and asthma severity,” Prof. Leuppi explained. This correlates with poorer asthma control. In an epidemiologic study published inLancet Respiratory Medicine by Price et al. this correlation could be statistically proven [9]. Eosinophil counts in blood and sputum and elevated levels of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) act as clinical biomarkers of eosinophilic asthma [7]. Increased activation and recruitment of eosinophils has a pro-inflammatory effect. Under the influence of chemokines, eosinophils migrate from the bone marrow to the bronchial walls. There they accumulate and activate mediators, which contributes to the damage of the respiratory tract. According to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), an eosinophilic phenotype is present in approximately half of all cases of severe asthma [8].

The term “type 2 low asthma” is used to describe a phenotype that has not yet been fully characterized, in which there is no evidence of allergy, no evidence of increased numbers of eosinophil granulocytes in the lungs or blood, and no evidence of Th2-induced inflammation (Tab.1). The “non-type 2 asthma” is relatively rare, summarizes Prof. Leuppi and advises differential diagnostic clarifications if a patient with severe asthma has low type 2 markers [1].

Reduction of systemic steroids through the use of biologics

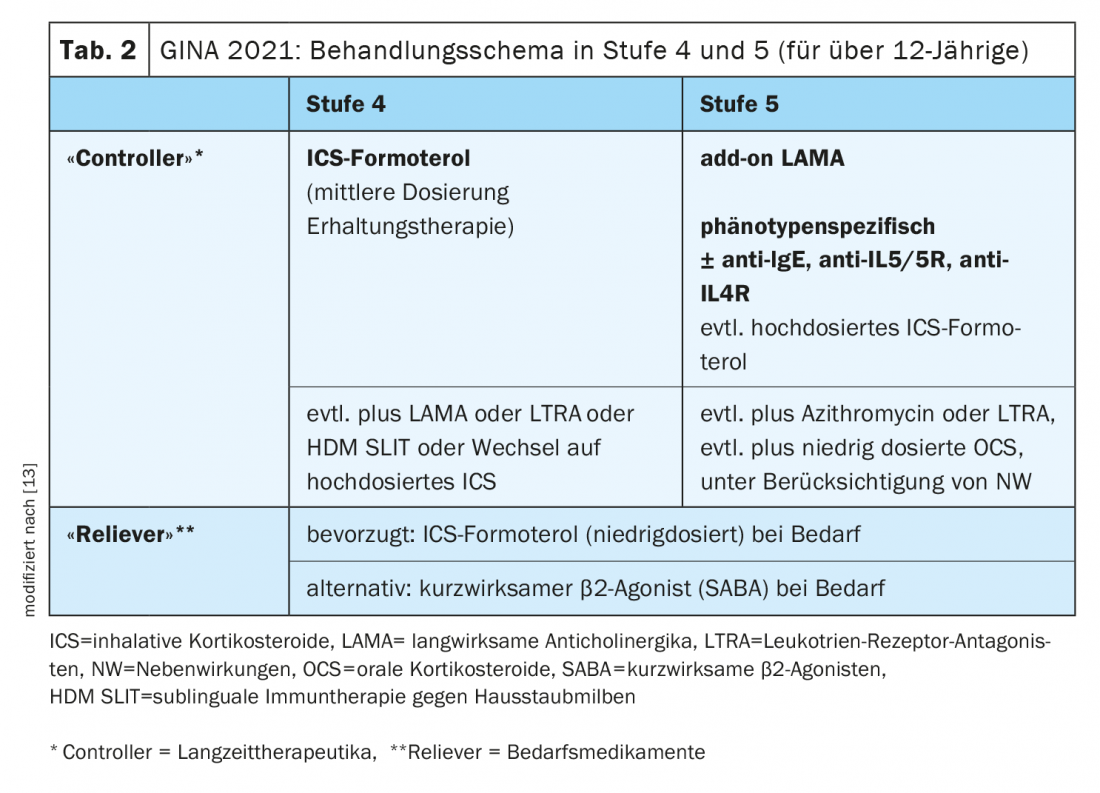

Asthma treatment is based on a treatment cycle in which therapy is regularly assessed, adjusted, and response is subsequently reviewed [10]. The treatment regimen proposed by the Global Initiative for Asthma includes five stages of asthma treatment. In stage 5, add-on treatment with a phenotype-specific biologic is nowadays recommended as maintenance medication in addition to ICS-LABA (Tab. 2). The long-term goals of asthma management are good symptom control and minimization of the risk of exacerbations and drug-related side effects. Long-term use of systemic oral steroids (OCS) increases mortality and complication rates, as shown by data from various prospective and retrospective studies, explains Prof. Leuppi. Therefore, in severe asthma (escalation from stage 4 to stage 5 according to GINA), initiation of antibody therapy should be considered after controlling inhaler technique and risk factors for patients who have eosinophil or allergic biomarkers. This may reduce the long-term use of OCS. The current GINA guideline provides for OCS in severe asthma only in exceptional cases, namely when sufficient control cannot be achieved even with high doses of inhaled glucocorticoids in combination with long-acting bronchodilators (LABA and/or LAMA) and the administration of a biologic [11].

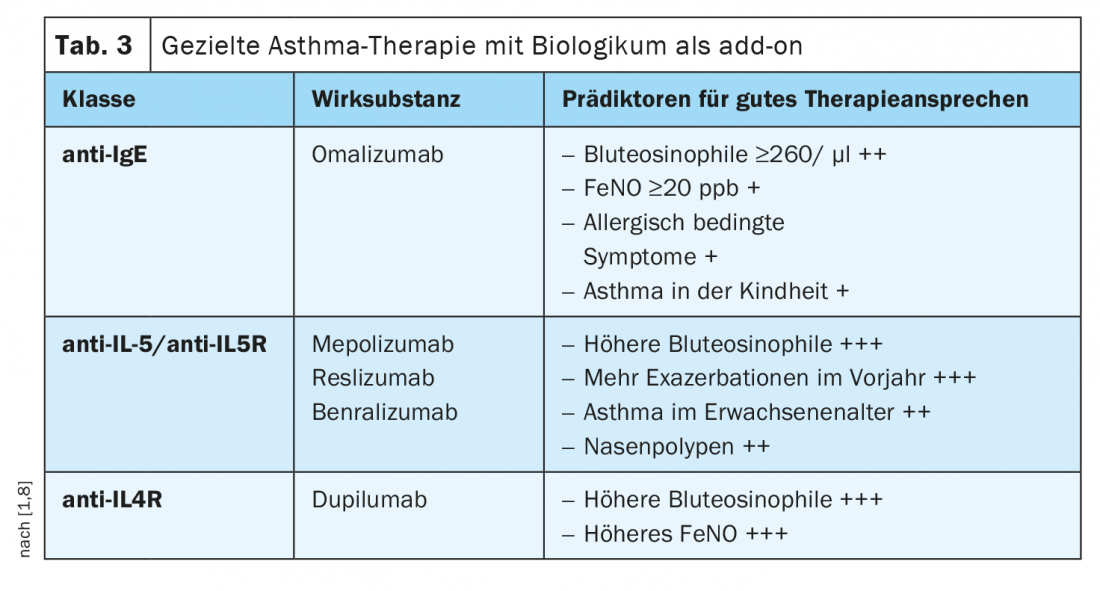

Match choice of biologic to patient characteristics

By determining biomarkers or phenotypes correlated with them, a prediction of the response to a respective antibody therapy is possible (Tab. 3) [1,8]. In case of perennial allergies and significantly elevated IgE concentration, the use of an anti-IgE antibody is useful. In cases of markedly increased blood eosinophilia (>300 cells/µl), monoclonal antibodies against interleukin-5 (IL-5) or IL-5 receptor antibodies are more appropriate, and in cases of eosinophilic asthma with an eosinophilia of >150 cells/µl and an increased FeNO fraction in exhaled air, therapy with an anti-interleukin-4 receptor antibody may be considered. If such a personalized treatment strategy is applied, asthma control can be significantly improved in many cases, which may also be reflected in a marked reduction in systemic steroids. [1]. The only humanized monoclonal antibody against IgE approved for asthma to date is omalizumab. This biologic acts by binding free IgE antibodies, resulting in lower free antibody levels and secondary to down-regulation of FcεRI on basophils and mast cells. Mepolizumab, reslizumab, and the IL-5 receptor antibody benralizumab are available for therapy directed against IL-5. While mepolizumab and reslizumab block cytokine signaling through highly specific binding to IL-5, thereby reducing eosinophil formation and survival, benralizumab interacts with both IL-5Rα and FcγRIII receptors on immune effector cells. The signaling pathway of IL-4 can be inhibited by the humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody dupilumab, which binds to the IL-4Rα and IL-13 receptor alpha (IL-13Rα) receptors.

The speaker pointed out that the GINA recommendations also apply during the Corona pandemic and that regular use of asthma medications as prescribed is very important [3]. In parallel with drug treatment, it is important to determine any comorbidities and modifiable risk or trigger factors (e.g., allergen exposure, smoking) and adjust them if necessary.

Congress: Medical Congress Davos

Literature:

- Leuppi JD: How biologicals have changed asthma therapy. Prof. Dr. med. Jörg D. Leuppi, Medical Congress Davos, Feb. 11, 2022.

- Leuppi JD, et al: Benralizumab: targeting the IL-5 receptor in severe eosinophilic asthma. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2019; 108 (7): 469-476.

- Leuppi J: What’s new in asthma primary care: Practice 2021; 110(16). DOI:10.1024/1661–8157/a003760.

- BÄK/KBV/AWMF: National Health Care Guideline Asthma – 4th Edition, Version 1, 2020; DOI: 10.6101/ÄZQ/000469

- Bakakos A, Loukides S, Bakakos P: Severe eosinophilic asthma. J Clin Med 2019; 8(9): 1375.

- Kühn M, Dimitriou F, Steiner UC, et al: TH2 immune response: significance and therapeutic influence. Swiss Med Forum 2021; 21(0102): 13-17.

- Pavlidis S, et al: “T2-high” in severe asthma related to blood eosinophil, exhaled nitric oxide and serum periostin. Eur Respir J 2019; 53(1): 1800938.

- Global Initiative for Asthma: Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2020. https:// ginasthma.org, (last accessed 2202.2022).

- Price DB, et al: Blood eosinophil count and prospective annual asthma disease burden: a UK cohort study. Lancet Respirator Med 2015; 3(11): 849-858.

- Steurer-Stey C: Asthma. medix Guideline, updated: 11/2021, www.medix.ch (last accessed Feb. 22, 2022).

- Severe asthma: oral glucocorticoids take a back seat. Allergo J 2020; 29: 74, https://doi.org/10.1007/s15007-020-2557-7

- Wang E, et al: Characterization of severe asthma worldwide: data from the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR). Chest 2020; 157: 790-804.

- Global Initiative for Asthma: Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2021. https://ginasthma.org, (last call 2202.2022)

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(3): 26-27