Regular physical activity can significantly reduce the risk of developing dementia as well as delay the onset of the disease. This activity should start as early as possible, but positive effects can still be measured when it starts late. At least 2-3 aerobic training sessions per week, each lasting at least 30 minutes, are recommended. The “ideal” physical activity does not exist. However, it makes sense to choose an activity in which there is personal experience in order to minimize the risk of injury. The article provides an overview of current research.

The incidence of dementia is increasing worldwide and there is no end in sight to this trend given the age dependency of the disease as well as demographic trends. The search for effective therapies continues, but most research approaches in recent years have not shown positive results and have not progressed beyond Phase III trials. Against this background, effective dementia prevention is particularly important. Delaying the onset of dementia by just a few years would be a great success, both medically and economically. Regular physical activity can be an important part of such a prevention concept, as it significantly reduces the risk of developing dementia if started early enough.

Background

Physical activity plays an important role in the prevention and treatment of neurological diseases and is widely recommended [1]. But can this connection really be proven with regard to the prevention of dementia? And what factors play a role in this?

With increasing life expectancy of the world population, an increase in dementia-related diseases is to be expected. Their prevalence is expected to double by 2050. In Germany, there are currently about 1.1 million dementia patients; in Switzerland, it is assumed that there are currently about 110,000 affected persons. Unless there is a breakthrough in prevention and therapy, projections of population development in Germany alone indicate that the number will increase to about 2.6 million by 2050. In other words, between 6 and 9% of the population over the age of 65 suffers from a dementia process.

Delaying the onset of dementia would have enormous health economic consequences in addition to patient-related benefits. According to the results of animal and epidemiological studies available to date, there is evidence that physical activity is neuroprotective and can delay cognitive decline in the context of chronic neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer-type dementia. Although preventive measures cannot currently provide certain protection against dementia, the importance of a relative risk reduction is shown by the fact alone that even an average delay of one year in the onset of the disease would reduce the number of sufferers by about 9%.

Before the question of whether physical activity has an influence on cognition can be investigated, a problem already arises: The definition of physical activity is handled very differently; in addition to sport in the narrower sense, the activities investigated include, for example, a physically demanding occupational activity, a high level of everyday activity, different durations and intensities, and different periods of activity, and are based in part on subjective assessments by the subjects or objective measurements (e.g., actigraphy, pedometer). In cohort studies, for example, a “physically active lifestyle” is often compared with an “inactive lifestyle” without any objective measurement of activity.

Effects of physical activity on cognition in healthy individuals.

Positive effects of physical activity on cognition in healthy individuals have been well studied [2]. In this context, various intervention studies examined a more or less structured program of physical or sporting activity. First, short-term effects can be measured: submaximal aerobic exercise of up to one hour duration improves information processing in healthy individuals. Prolonged stress leading to dehydration, on the other hand, worsens information processing and memory. In addition, there are medium- to long-term effects: A meta-analysis of 29 randomized controlled intervention trials in adults without dementia found that aerobic exercise resulted in modest improvements in attention, processing speed, executive function, and memory.

Special attention has been paid in intervention studies to the target group of older persons who are still cognitively healthy. Even in this age group, significant improvements in cognitive performance are predominantly found with regular physical training.

Dementia prevention through physical activity?

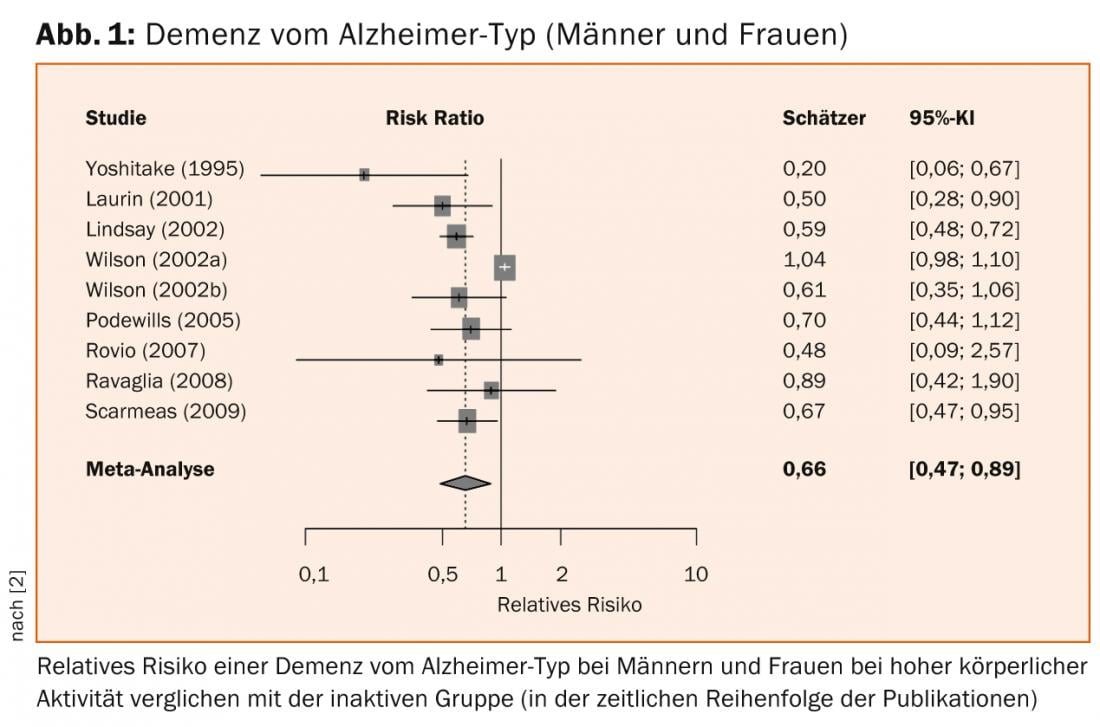

Numerous prospective cohort studies are available on the question of whether physical activity can prevent dementia. These were evaluated meta-analytically [2]. Slightly different results were shown here for different forms of dementia. In particular, dementia of the Alzheimer’s type can be prevented or at least delayed by regular physical activity (relative risk = 0.66 of developing dementia in the most physically active compared with the most inactive individuals, Fig. 1).

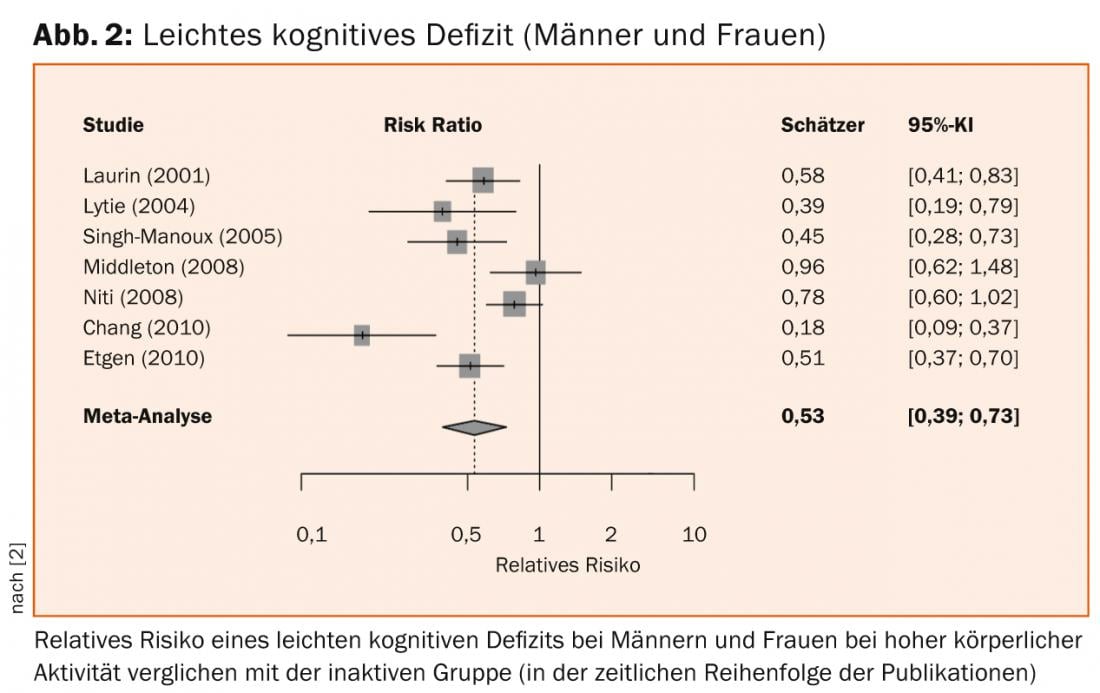

Overall, physically active individuals had a 25% reduced risk of developing dementia compared with inactive individuals. The risk of mild cognitive deficit, effectively a precursor of dementia, was reduced by as much as 47% in physically active individuals (Fig. 2).

Other authors also conclude in meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies of healthy individuals that the risk of cognitive decline is reduced by 28-45% within one to twelve years with high levels of physical activity [3–5]. Light to moderate physical activity also significantly (by 35%) reduced the risk. Thus, the results of these meta-analyses are all in the same order of magnitude, so that it can be assumed that regular physical activity is a protective factor against the development of dementia. Admittedly, there are no randomized controlled intervention trials with physical activity. These will probably not exist in the future either for ethical reasons.

Possible mechanisms of dementia prevention

The mechanism by which the dementia-preventive effect is achieved and which types of exercise are best suited for this purpose in terms of intensity and duration have not yet been clarified. Possible factors include improvement in cerebral blood flow and metabolism, reduction of oxidative stress in the brain, and decreased formation and improved degradation of Aβ-amyloid. Animal experimental data also indicate that there is not only a unidirectional relationship between the central nervous system (control of muscle function), but a bidirectional relationship. Thus, physical activity leads to metabolic reactions even beyond the brain regions directly involved in the movement (“molecular crosstalk”). Furthermore, physical activity in the brain can release neurotrophins and growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and nerve growth factor (NGF), which stimulate cerebral neurogenesis and angiogenesis. Physical activity has also been shown in animal experiments to influence cerebral neurotransmitter systems such as serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and acetylcholine. In one paper, it was shown that regular aerobic activity of three times an hour per week for six months in 60 – to 79-year-olds leads to a significantly increased volume of gray and white brain matter [6]. Non-aerobic exercise was ineffective in this study. Young people, on the other hand, showed no significant increase in volume. In addition, regular physical activity has a positive effect on factors for which an increased risk of dementia is discussed, namely glucose intolerance and hypercholesterolemia. A detailed discussion of the possible mechanisms of action of physical activity has been provided by Lista and Sorrentino [7] and Radak et al. [8] published.

So what’s the bottom line?

Regular physical activity can have a positive impact on cognitive performance in both the short and long term. In principle, this still applies at a very old age – the preventive effect can also be demonstrated in people over 85 years of age [9]. While a causal therapy in the early stages of Alzheimer’s dementia is not yet in sight, physical activity seems to be a promising preventive measure. Regular physical activity (mainly aerobic activity was studied) reduces the risk of cognitive decline by about 25 (undifferentiated dementia),

34 (Alzheimer-type dementia) and 47% (mild cognitive deficit). This – among numerous other health-promoting effects – is another reason for regular physical activity.

Although the above-mentioned results from prospective cohort studies demonstrate a statistical association between physical activity and dementia, the question of causality cannot yet be answered.

Thus, concrete recommendations on the type and duration of physical activity that has a dementia-preventive effect are difficult according to current knowledge. As a rough guide, however, we know at least from intervention studies in healthy individuals that beneficial health effects can be demonstrated with regular physical activity of at least two to three sessions per week, each lasting about 30 minutes.

Whether physical activity also has a preventive or therapeutic effect for already cognitively impaired individuals has not been proven beyond doubt according to current knowledge. However, several randomized controlled intervention trials and a meta-analysis [10] suggest that physical training can still somewhat improve cognitive performance in older persons even with mild cognitive deficit or dementia, or at least slow further cognitive decline.

Literature:

- Pfeifer K, et al: Physical activity promotion and sport in neurology – competence orientation and sustainability Neurol Rehabil 2013; 19 (1): 7-19.

- Felbecker A, et al: Cognitive disorders. In: Reimers CD, et al. (Eds.): Prevention and therapy of neurological and mental diseases through sport. Elsevier Verlag 2013; 443-474.

- Hamer M, Chida Y: Physical activity and risk of neurodegenerative disease: a systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychol Med 2009; 39: 3-11.

- Lautenschlager NT, Almeida OP: Physical activity and cognition in old age. Curr Opin Psychiatr 2006; 19: 190-193.

- Sofi F, et al: Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Intern Med 2011; 269: 107-117.

- Colcombe SJ, et al: Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006; 61: 1166-1170.

- Lista I, Sorrentino G: Biological mechanisms of physical activity in preventing cognitive decline. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2010; 30: 493-503.

- Radak Z, et al: Exercise plays a preventive role against Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2010; 20:777-783.

- Denkinger MD, et al: Physical activity for the prevention of cognitive decline: current evidence from observational and controlled studies. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 45: 11-16.

- Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ: The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: A metaanalysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1694-1704.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(3): 5-7.