Visceral surgery patient volumes have increased significantly in recent years. After major surgery with opening of the abdominal wall due to chronic, oncological or acute diseases, almost all patients suffer from muscle weakness, reduced physical functionality as well as reduced cardiopulmonary performance. This means that there are two important treatment priorities in rehabilitation: on the one hand, optimal and complication-free care of the surgical wound, and on the other hand, the best possible reconditioning of physical performance in order to achieve mobility and independence. Thus, postoperative follow-up should be multidisciplinary and supplemented by detailed education and instruction of the patient for abdominal wall-sparing behavior in training and therapy.

According to the results of a survey [1], specialists give different guidelines as to where the limits of stress should be set and which activities and movements can be allowed in which phase of rehabilitation. There is agreement that the intraoperatively opened abdominal wall must be relieved within the wound healing phases, six weeks to three months depending on the severity, to ensure optimal wound closure and avoid complications.

For the therapist, this poses the challenge of ensuring an everyday abdominal rehabilitation training program that is gentle on the abdominal wall, with training-effective intensity, but without structurally overstraining the abdominal scar.

Medical basics

Detailed knowledge of the postoperative structural resilience of opened tissue has existed for a very long time. Thus, various authors reported that an opened tissue segment will never regain full loading capacity [2]. Immediately after wound closure, the load-bearing capacity of the tissue is reduced by about half. Even after a year, it usually has less than 90% of its original load-bearing capacity. Furthermore, opened skin tissue can be expected to bear weight faster than the injured muscle tissue underneath [3]. In the field of medical and surgical technology, great progress has been achieved with laparoscopic operations. Where appropriate, smaller incisions can be made, resulting in less tissue damage. Optimally, this results in faster wound healing, less pain, and rapid patient recovery [4].

If the abdominal wall is stressed too early, wound and scar healing may be delayed and possibly tears in the deep scar tissue may occur. Mechanical stability can also be reduced in the long term [5].

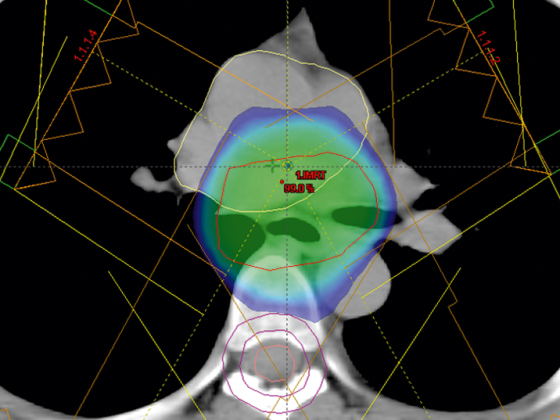

Other complications include incisional hernias or fractures, infections, and increased pain. In addition to mechanical compressive and tensile loads due to abdominal muscle activity, intra-abdominal pressure and abdominal wall tension are other key influencing variables of abdominal wall sparing that are much more difficult to measure. The abdominal scars after visceral surgery shown in Figure 1 give an idea of how important post-operative treatment that is as free of tension as possible is for wound healing.

Procedure and specifications

Surgeons’ information for postoperative follow-up varies widely. The general guidelines range from “lift a maximum of five kilograms for six weeks” to “load according to symptoms”. Specific restrictions range from “bicycle ergometers only allowed after the fourth week” to “bicycle ergometers generally allowed.” These differences are certainly due to the individuality of the patient and indication (age, expected wound healing with secondary diagnoses such as diabetes, obesity, tissue, incision, etc.).

It should also be noted that taking pain medication affects both body awareness and pain perception. As a result, the therapist does not necessarily have the assurance that painless exercises generally do not represent tissue overload.

Abdominal wall protection in everyday life

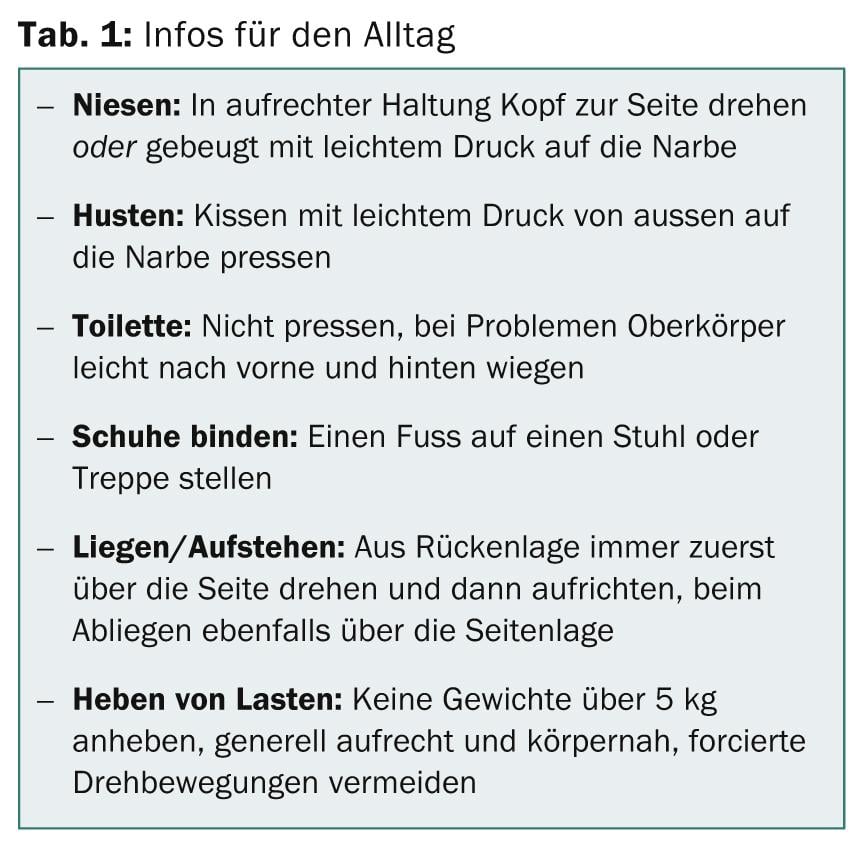

Inpatient rehabilitation fundamentally pursues the goal of reintegrating patients as quickly as possible into their familiar environment with the greatest possible independence, taking a holistic view. From the first postoperative day onwards, situations inevitably arise which may place too much stress on the abdominal wall. This requires good training and instruction of the patient on self-care and proper handling of these situations. Medical precautions must be taken (Figs. 2 and 3) to facilitate patient compliance.

Thus, constipation or prostate obstruction can lead to pressing maneuvers when going to the toilet, which massively increase the tension of the abdominal wall. Coughing, sneezing, and laughing are also in a category that is difficult for the patient to control and require good information and instruction from all disciplines involved (Table 1).

It is possible to use an abdominal belt to relieve the scar and stabilize the torso with light pressure at the same time. Patients usually find this subjectively pleasant. Often, wearing an abdominal belt is even mandatory within the post-treatment regimen.

Abdominal wall protection in training and therapy

The above-described eduction and instruction of the patient with regard to abdominal wall-protecting behavior in everyday life is uniformly taught within an inpatient rehabilitation by all disciplines such as nursing, medicine and therapy. The physiotherapists and sports therapists are responsible for individual and practicable training and exercise programs. There, too, the patient should have a consistent picture of which movements are feasible in the build-up training and which represent a possible overuse. The goal is to increase the amount and intensity of physical activity as wound healing progresses.

Strength training and medical training therapy

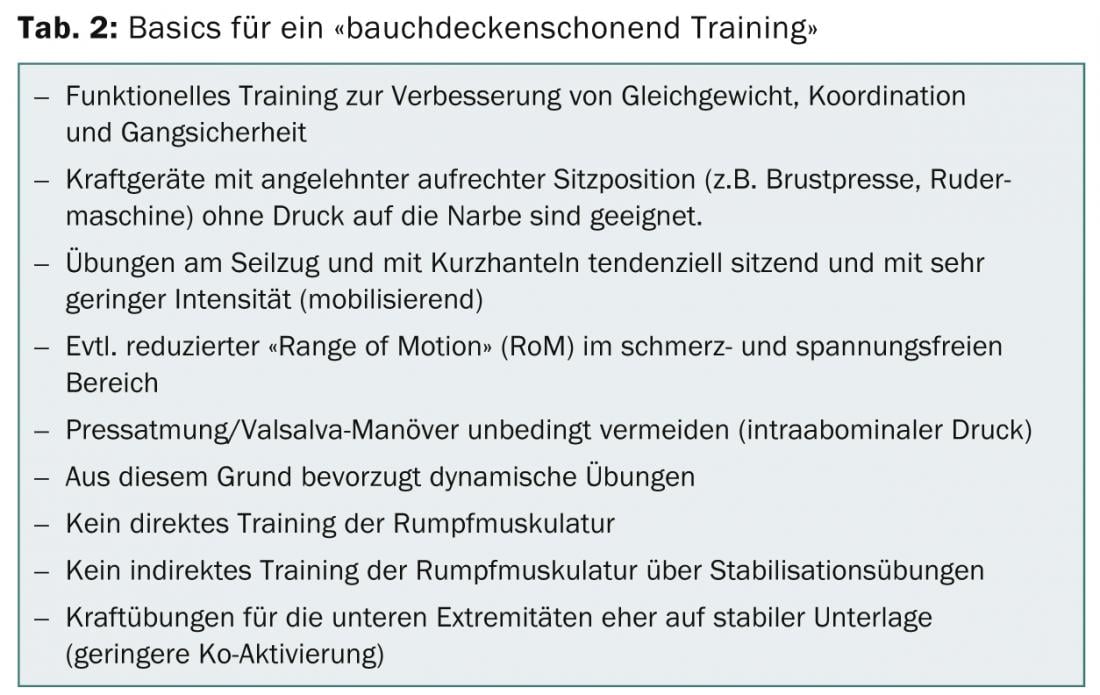

Numerous strength exercises result in stabilizing co-activation of the trunk muscles, which is difficult to avoid [6]. This mechanism, which is necessary for the posture and statics of the body, is desired in general strength training and in most cases is deliberately sought and provoked in order to make the exercises functional and holistic. In the case of a postoperative abdominal wall-sparing procedure, this mechanism, being difficult to control and monitor, should be minimized if possible.

In a pilot study [1] of the Zurich High Altitude Clinic Davos, surface EMG was used to compare the abdominal muscle activity of healthy subjects during various strength exercises with the measured values of everyday activities. This made it possible to create a catalog of suitable and unsuitable exercises, which probably cannot be transferred 1:1 to training with patients, but which makes it possible to base the selection of exercises on comprehensible data. In concrete terms, this shows that classic strength training equipment such as the rowing machine, chest press or leg press can also be performed at higher intensities without risk if the upper body can be relieved by leaning against it. In contrast, free exercises with dumbbells or on a pulley clearly exceed all ADL loads even at medium intensity.

In a seated starting position with the upper body leaning, numerous exercises on the pulley are associated with a significantly lower co-activation of the trunk muscles. Table 2 summarizes the key principles of abdominal wall-sparing training.

Ergometer training

As described above, there are definitely different assessments as to whether endurance training on the bicycle ergometer is feasible and, if so, at what stage. The added value of submaximal cardiopulmonary training is undisputed: stabilization of the cardiovascular system, activation of muscles and metabolism, improvement of body perception and self-esteem. As with other exercises, the intensity, volume and choice of equipment itself are key. The subjective feeling of the patient is absolutely paramount here. Overloading and overtraining must be avoided at all costs.

The following image comparisons (Figs. 4 and 5) show the difference that the seating position and pedal adjustment makes, especially for overweight patients or patients with an ileostomy.

The flexion in the hip joint in Figure 5 is significantly smaller with a shortened pedal radius and adapted seat setting, and thus the movement and “restlessness” in the abdominal space is significantly smaller. At first glance, this aspect seems very banal, but in practice it has been shown that especially in postoperative obese patients or patients with an ostomy, training without shortening the pedal radius is subjectively unpleasant to painful and thus contraindicated. The associated reduction in leverage and increase in pedaling effort can be compensated for by lower wattage training. Alternatively, of course, a walk training on the treadmill, evt. with a slight incline, can be selected to control the cardiovascular workout. Other machines such as rowing ergometers, upper-body ergometers or cross trainers should be avoided due to the activity of the core muscles.

Discussion

As with other postoperative restrictions, e.g., partial weight-bearing after hip TEP, it is apparent that the patient neither fully complies nor can realistically comply with the prescribed procedures in everyday life [7]. This also makes it clear that, in addition to the generally applicable guidelines, patients should also be informed, instructed and advised individually on the basis of their situation and their questions and fears. Excessive protection of the abdominal wall must be cautioned against, as this may promote unnecessary soft breathing, immobilization or constipation. After wound healing is complete, it is important to progressively train the trunk muscles that were relieved during the “grace period” to prevent imbalances and muscle weaknesses. This information should not be withheld from the patient either, so that he can regain confidence in his body and resilience.

If all aspects are taken into account, there is nothing to prevent active training of the patient at an early stage after visceral surgery, thus ensuring holistic rehabilitation. This is also not unimportant from a health economic point of view: A faster reconditioning and independence and thus also a shorter length of stay in the rehabilitation clinic can be expected.

Silvio Catuogno

Sandra Brülisauer

Literature:

- Strub C, et al: EMG based conclusions for an abdominal gentle medical training therapy. Swiss Med Wkly 2009; 139 (7-8): 169.

- Fast J, Nelson C, Dennis C: Rait of gain in strength in sutured abdominal wall wounds. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1947; 84: 685-688.

- Ellis H: The cause and prevention of postoperative intraperitoneal adhesions. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1971; 133: 497-511.

- Schwenk W, et al: Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane database 2001.

- Vogt HJ: Scars. Hippokrates Verlag; Stuttgart 1993; 15-19.

- Arokoski JP, et al: Back and abdominal muscle function during stabilization exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2001; 82(8):1089-1098.

- Klöpfer-Krämer I, Augat P: Partial loading in rehabilitation. The Trauma Surgeon 2010; 113(1): 14-20.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(6): 12-16.