Reactive plasmocytoses are rare, but then often pronounced. They must be differentiated from reactive (polyclonal) and monoclonal plasma cell proliferation. A precise differential diagnosis enables effective therapy.

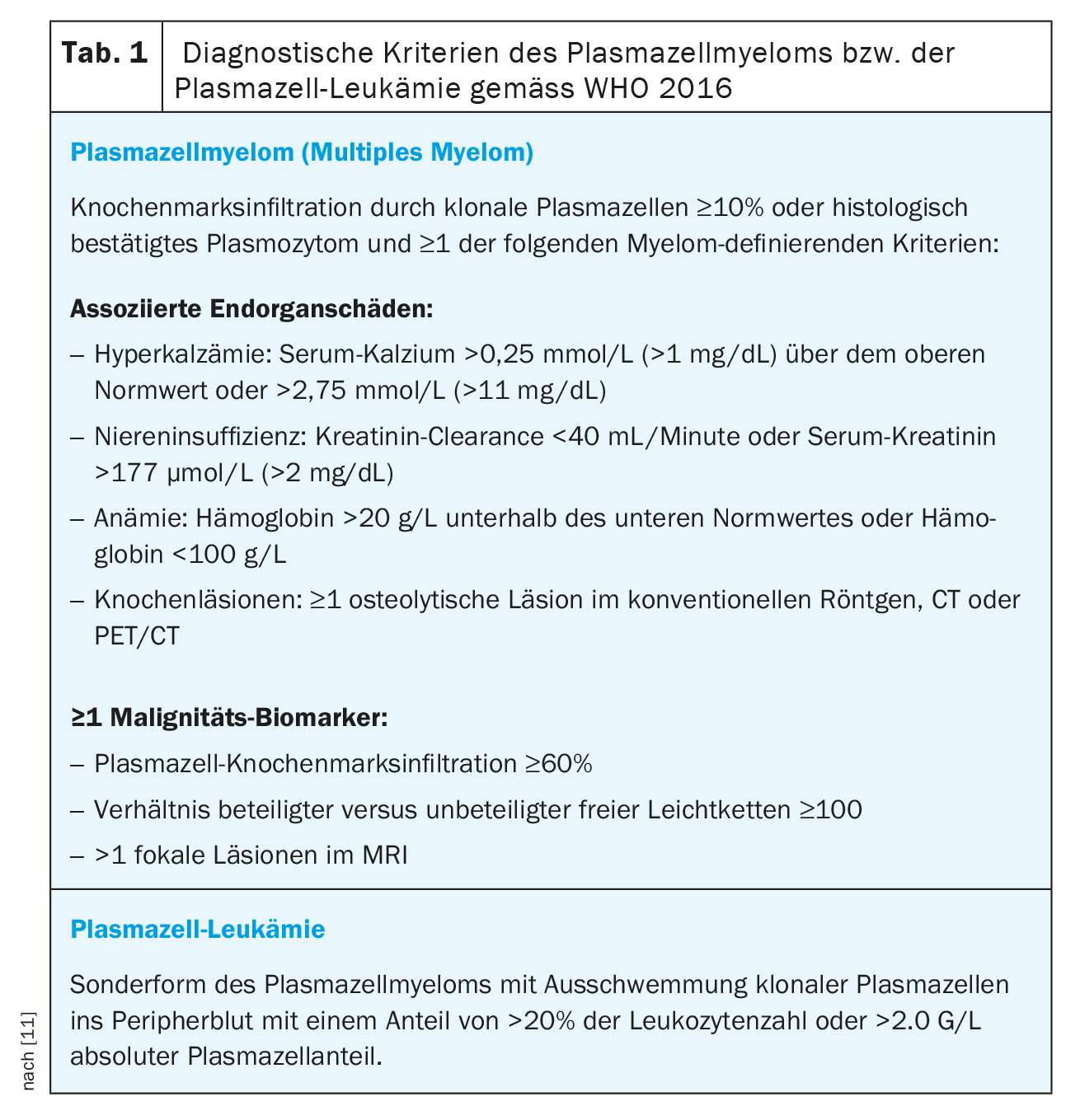

Reactive plasmocytosis was first described in 1988 as polyclonal plasma cell proliferation in peripheral blood and is rare overall [1,2]. The diseases associated with reactive plasma cell proliferation include non-neoplastic processes such as autoimmune diseases, infections, and substrate deficiency anemias on the one hand, and malignant neoplastic processes, especially hematologic tumor diseases, on the other hand [3,4]. The extent of plasma cell proliferation is mild in most cases and often limited to the bone marrow, but marked plasmocytosis is possible and may lead to a suspected diagnosis of plasma cell leukemia (Table 1)[3–10].

Case Report

A 70-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department of a regional hospital due to acute aggravated dyspnea. Two weeks earlier, the primary care physician initiated antibiotic therapy with a clinical picture of pneumonia. Due to persistent dyspnea beyond antibiotic therapy, a CT chest was performed, which revealed subsegmental pulmonary emboli on both sides as well as diffuse lymphadenopathies up to a maximum diameter of 16 mm. Oral anticoagulation with edoxaban was established, and workup of lymphadenopathies was planned.

In the emergency department, the patient presented tachydyspneic with a respiratory rate of 35/min and an oxygen saturation of 93% below 5 liters of oxygen per minute. The vital signs were otherwise as follows: BP 119/81 mmHg, pulse 81/min, temperature 35.6°C. Physical examination revealed obstructive breath sounds and inspiratory stridor. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Due to the obstructive breathing, a trial dose of 125 mg methylprednisolone was administered, which led to a partial regression of the dyspnea.

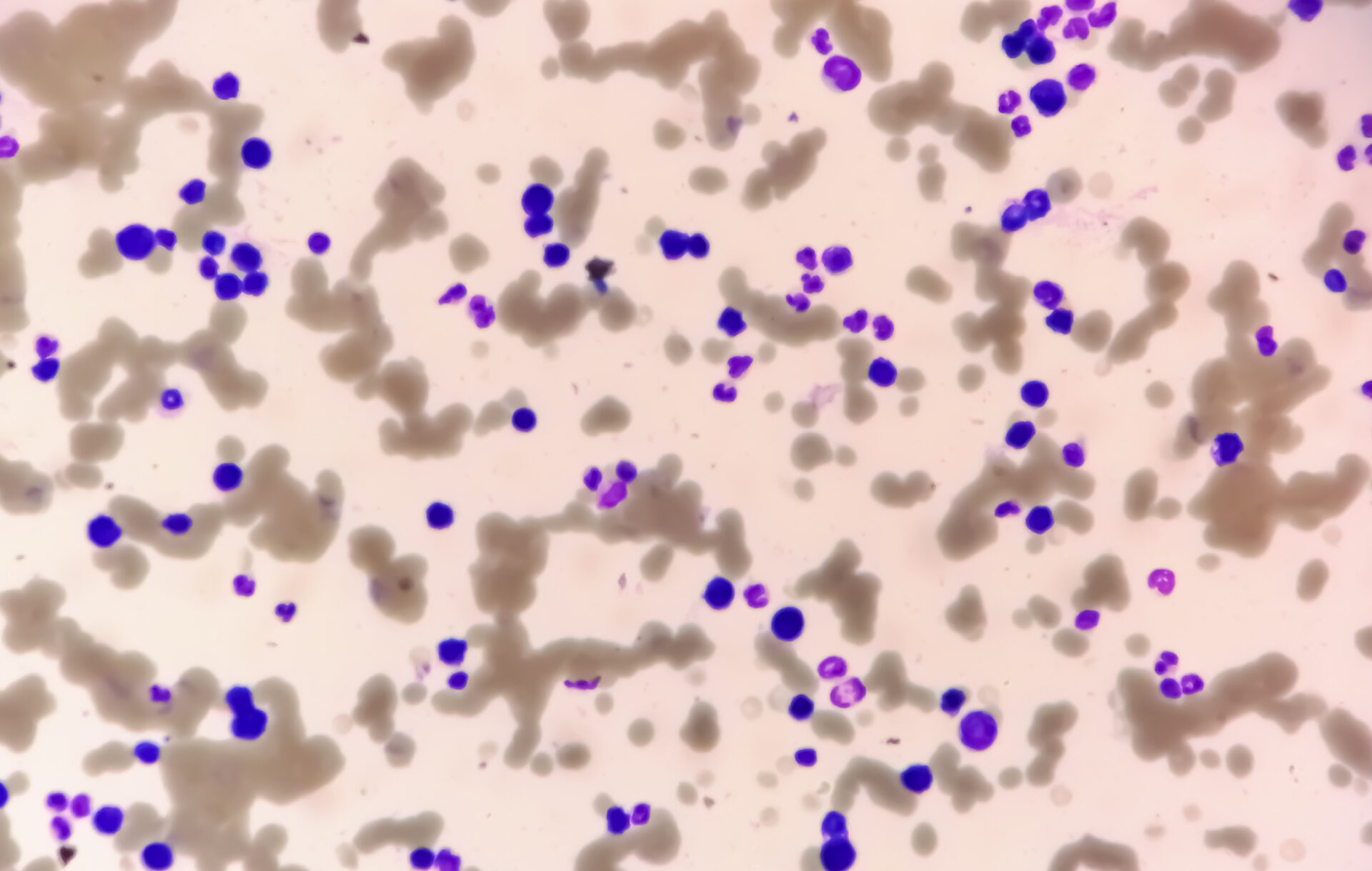

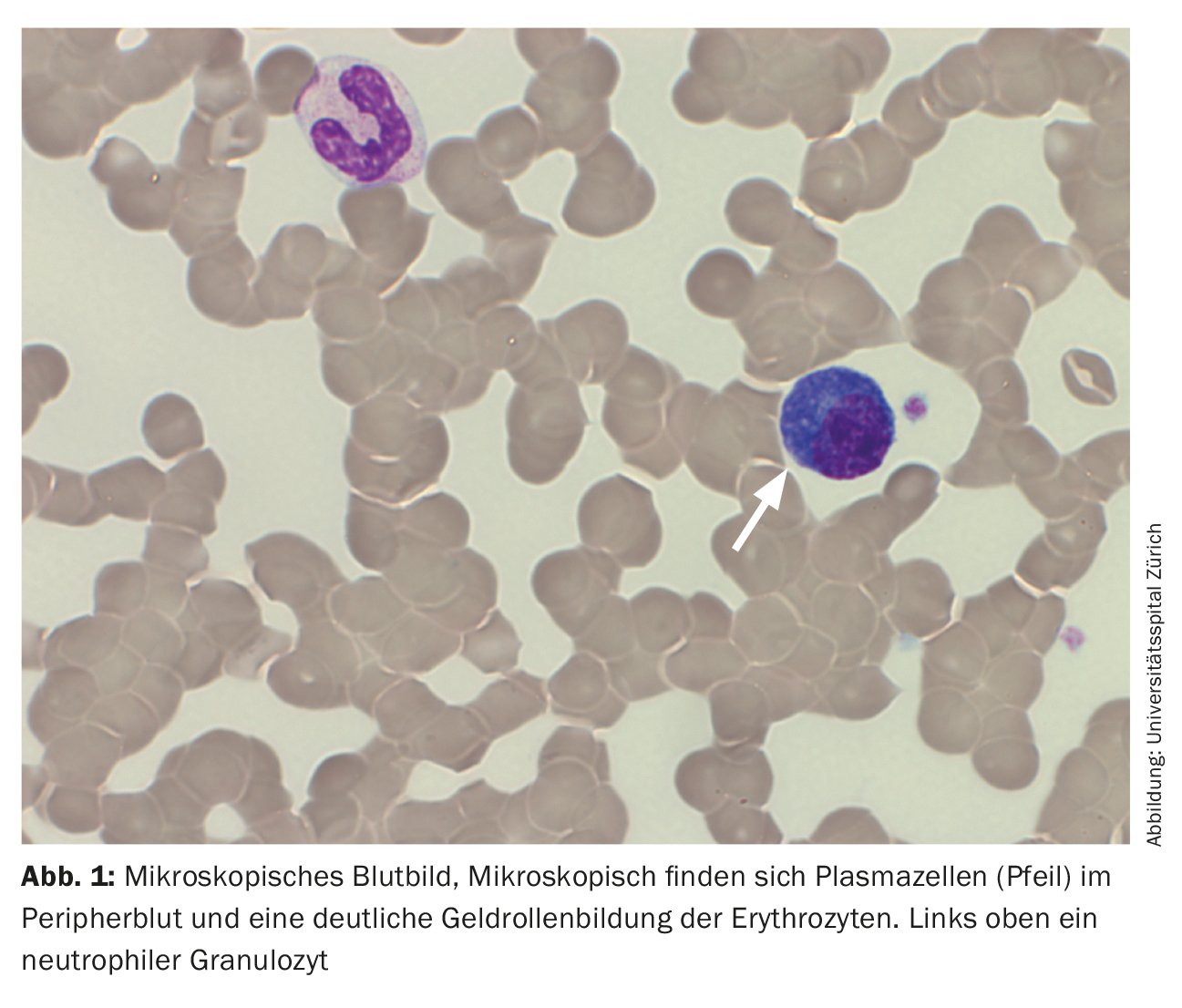

The peripheral blood showed anemia with a hemoglobin of 77 g/L, normal platelet values and a leukocytosis of 20.4 G/L, caused by a washout of 29.5% plasma cells. In addition, a strong gel roll formation of erythrocytes was found as an indication for the presence of paraproteinemia. In line with this, there was an increased total serum protein of 106 g/L (reference range: 62-80 g/L) with a slightly lower albumin of 28 g/L (reference range: 32-46 g/L) and increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 987 U/L (reference range: 232-430 U/L).

This constellation of findings led to a tentative diagnosis of plasma cell leukemia, and the acute dyspnea was interpreted as a possible sign of hyperviscosity syndrome. Therefore, the patient was referred to our center hospital for evaluation of plasmapheresis.

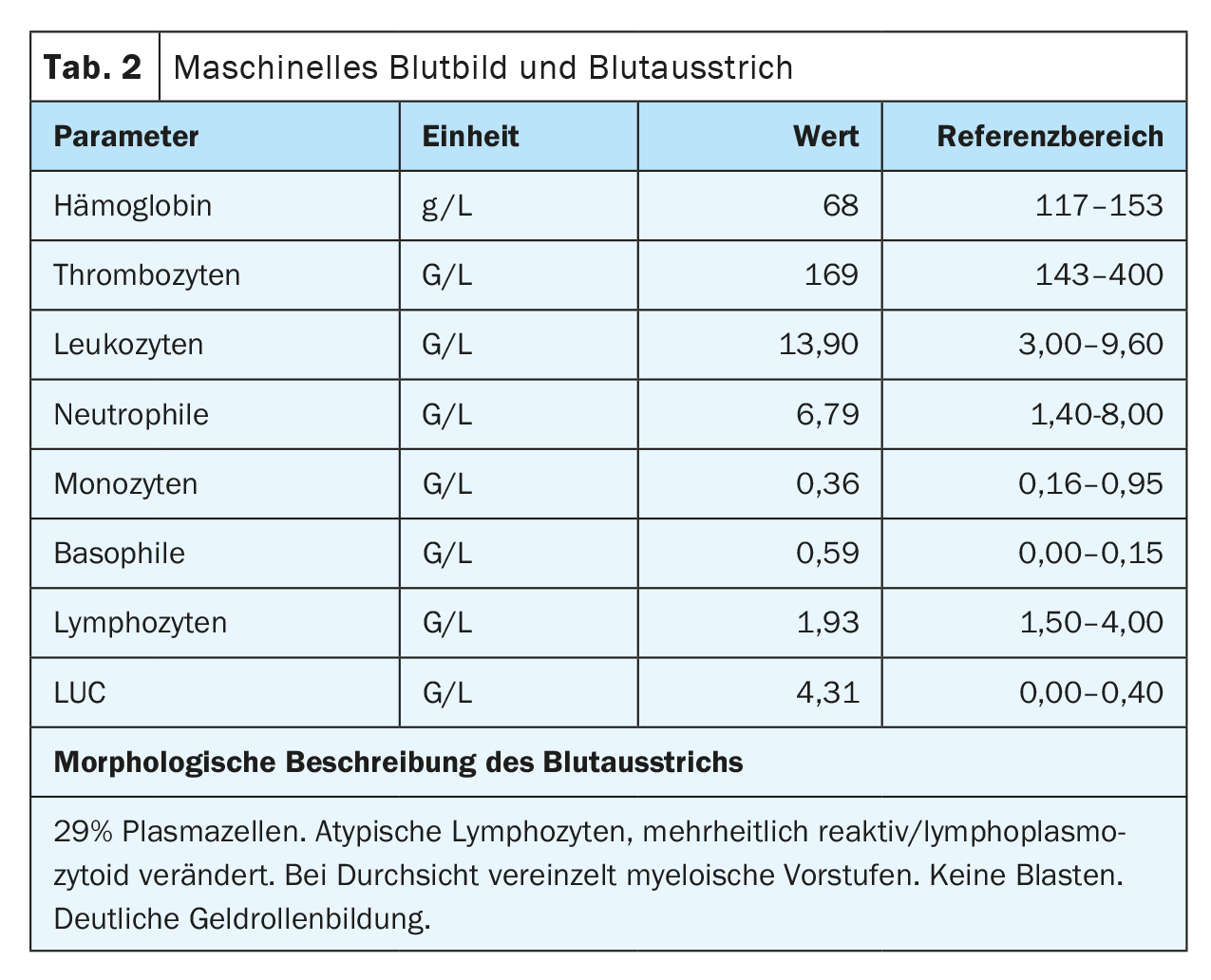

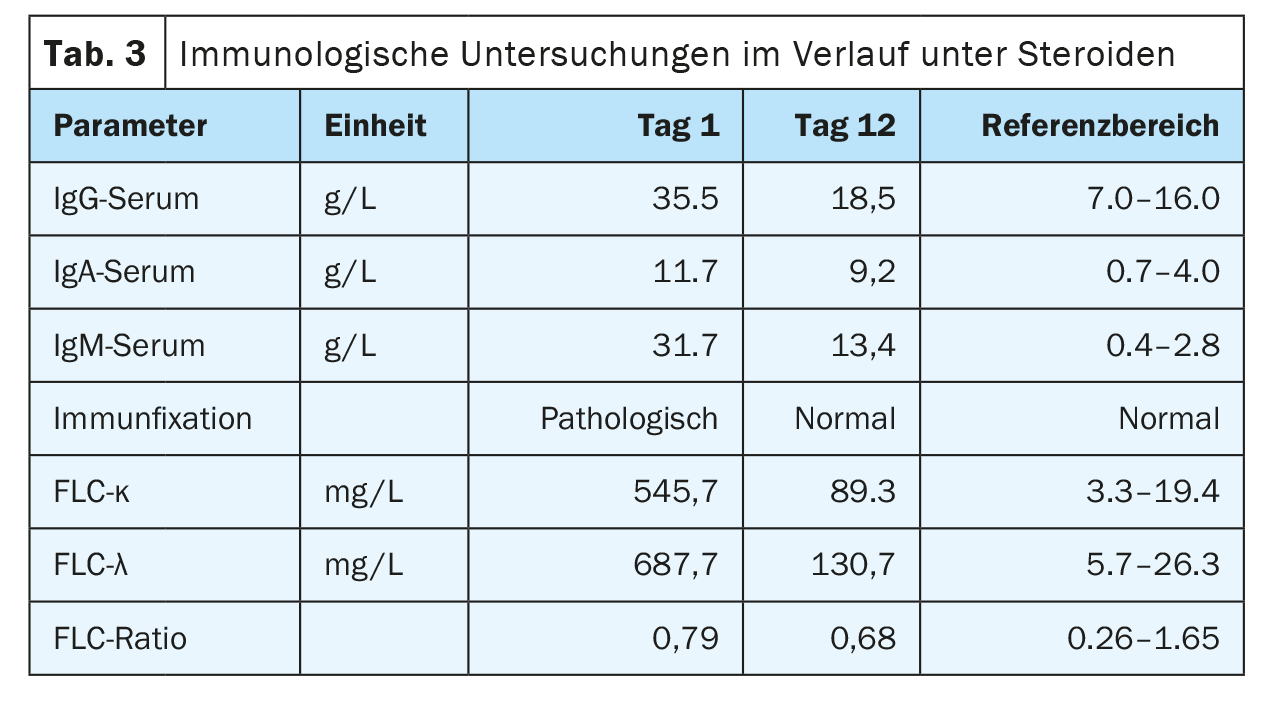

On admission, the patient was in a cardiopulmonary stable condition with compensated respiratory status. No other symptoms requiring treatment, possibly associated with hyperviscosity, were found, so there was no indication for plasmapheresis. The impressive external finding of peripheral 29% plasmocytosis was confirmed (Tab. 2) (Fig. 1). Further blood analysis revealed a marked increase in immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, IgA) as well as free light chains in the serum, but the light chain ratio was inconspicuous. (Tab. 3). A broad IgM lambda band was detectable in the immunofixation, but no reliable differentiation between a clonal band with di-/multimerization and a polyclonal pattern was possible. The β2-microglobulin was also elevated at 17.6 mg/L (reference range <2.5 mg/L). For further diagnosis, clonality clarification of plasma cells by immunophenotyping had to be performed.

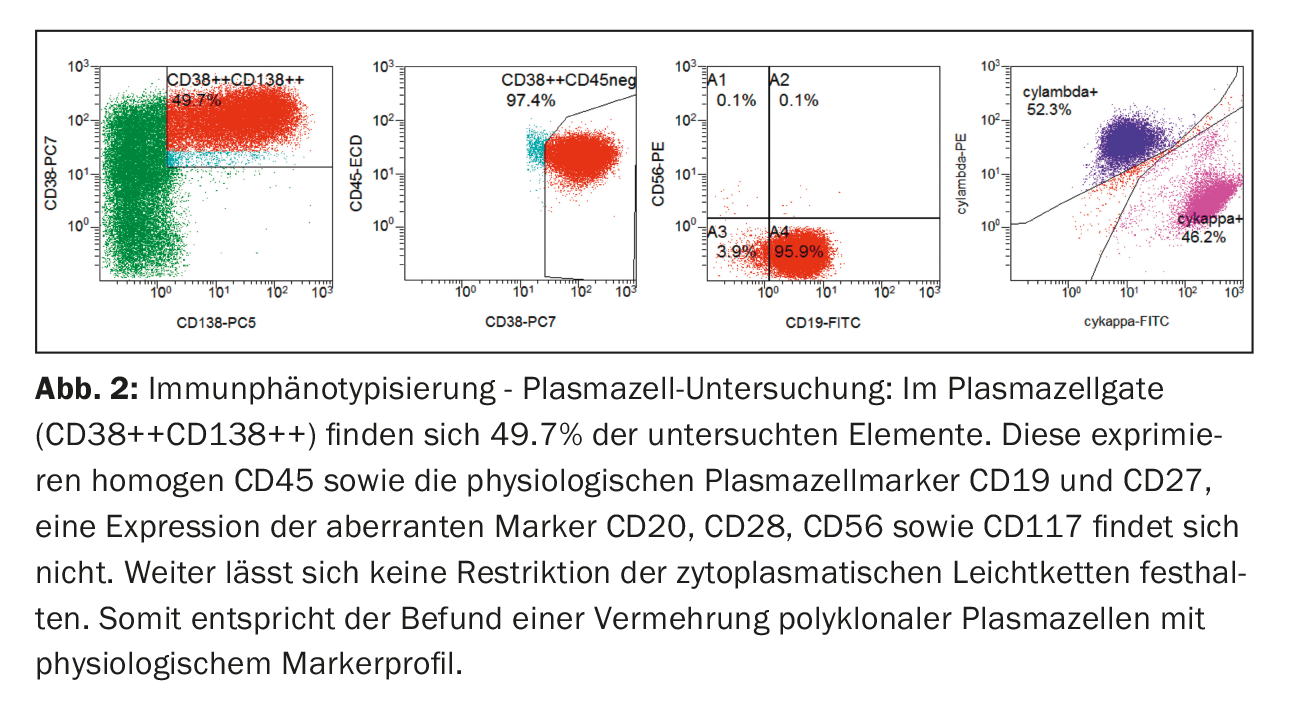

Immunophenotypically, plasma cells in peripheral blood were clearly increased in the classic plasma cell gate (CD38++CD138++). These showed expression of CD45 as well as the physiological plasma cell markers CD19 and CD27. Expression of aberrant markers (CD20, CD28, CD56 and CD117) was not found, nor was there any restriction of cytoplasmic light chains, so that in summary there was a proliferation of polyclonal plasma cells (Fig. 2) .

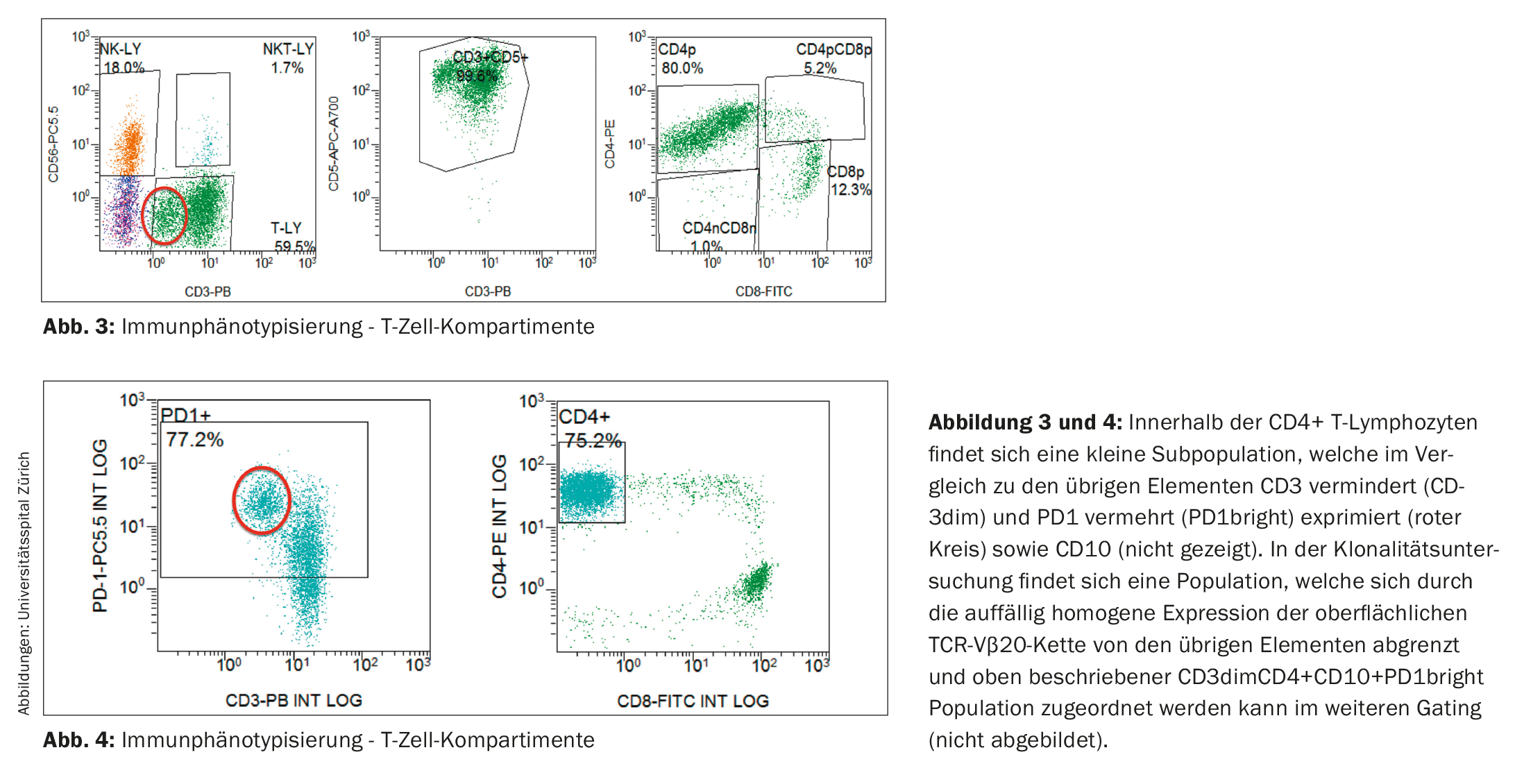

Immunophenotypic examination of lymphocytes was without evidence of a clonal B-cell population. In contrast, the T-cell compartment showed a shift of the CD4:CD8 ratio in favor of the CD4-positive T lymphocytes (in the present study 6.5:1; reference range in peripheral blood: CD4:CD8 ratio 2:1) as well as a small population with decreased CD3 expression (CD3dim) (Fig. 3). In the follow-up study, a CD4+CD3dimPD-1+CD10+ immunophenotype could be assigned to this abnormal population (Fig. 4) and it proved to be clonal to the TCR-Vβ20 chain based on TCR analysis. Thus, the finding was consistent with peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (T-NHL) of the angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) type.

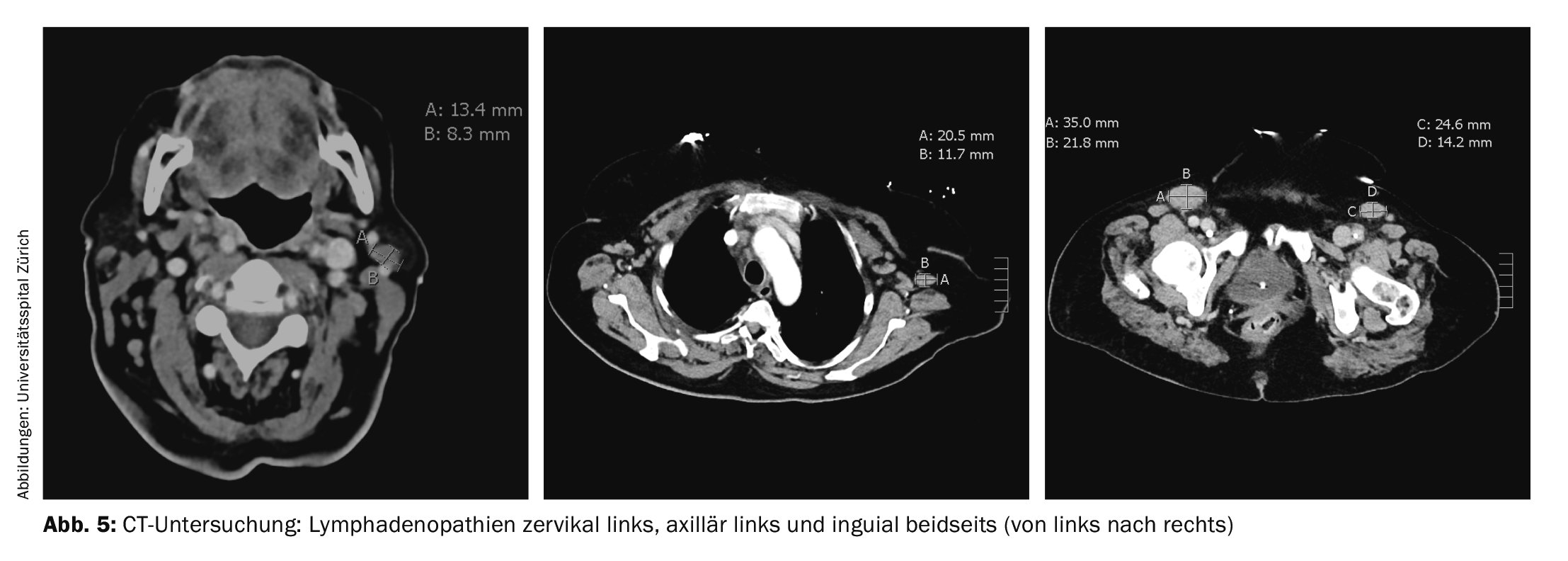

Because of persistent dyspnea, computed tomography was performed again. The examination did not reveal any evidence of pulmonary embolism, but several lymphadenopathies were found, the largest of which was inguinal on the left (35×22 mm) (Fig. 5). A consecutive right axillary lymph node excision was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL). Bone marrow examination showed medullary involvement by AITL with 10-15% infiltration and medullary polyclonal plasma cell proliferation by 20%.

This resulted in a diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) Ann-Arbor stage IV with reactive plasmacytosis (Fig. 6). Initially, cytoreductive therapy with high-dose corticosteroids was administered, which led to a rapid improvement in the clinical picture and a clear regression of hyperglobulinemia G/M/A in the short term (Table 3) . Once the diagnosis was confirmed, AITL-directed therapy with CHOP was initiated.

Definition

Plasmocytosis is defined as plasma cell proliferation in the peripheral blood and may be of neoplastic origin in the sense of clonal plasma cell disease, but may also be reactively caused [12]. Reactive plasmacytosis was first described in 1988 by Peterson et al. described as “Systemic polyclonal immunoblastic proliferations” in four patients with polyclonal plasma cell proliferation in peripheral blood[1,2].

In the literature, the term plasmocytosis is sometimes also equated with plasma cell proliferation in general and the affected compartment (peripheral blood, bone marrow, other tissues) is specified.

Epidemiology and etiology

Reactive plasmocytosis is a rare phenomenon with few reported cases, whereas reactive plasma cell proliferation in bone marrow is relatively common [13,14]. Batdorf et al. found a plasma cell proliferation (defined as >2.0% plasma cell percentage) in 8.8% (303/3435) in their analysis of 3435 bone marrow examinations. In a smaller study by Gupta et al. 830 bone marrow examinations were processed and plasma cell proliferation (defined as >3.5% plasma cell content) was recorded in as many as 13.7% (114/830) of cases. In both studies, plasma cell proliferation was due to plasma cell myeloma in less than 10% of cases [3,4].

As associated diseases of reactive plasma cell proliferation, non-malignant causes such as substrate deficiency anemias, hemolytic anemias, infections (especially also HIV), autoimmune diseases and liver diseases (especially in liver cirrhosis) have been observed on the one hand, but also malignant processes on the other hand. The latter in 15.7% to 55.4% of cases, the majority of which were hematologic tumors [3,4]. The extent of plasma cell proliferation was between 5-24% in non-neoplastic etiology, less than 10% in anemia and between 10-30% in infections and hypoplastic bone marrow [3]. Reactive plasma cell proliferation can also be caused by medication. For example, a study by Zamarin et al. found that polyclonal hyperglobulinemia and medullary plasma cell proliferation of 5-20% (median 12%) occurred in 20% of patients with plasma cell myeloma with prolonged exposure to lenalidomide (>6 months) [15]. This phenomenon is associated with prolonged progression-free survival; the mechanism is unclear.

There are only case reports of reactive plasmocytosis, but not unexpectedly the spectrum of underlying diseases is comparable: there are reports of plasmocytosis in the context of viral (acute hepatitis A, Ebstein-Barr virus, parvovirus B19, dengue, SFTS virus) but also bacterial infections (S. aureus, K. pneumoniae) [5,7,10,16–20]. One case was described in a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome [8]. Furthermore, several cases of pronounced plasmocytosis are found in association with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas and in one case even a connection with a coexisting plasma cell myeloma is postulated [6,9,13,21,22]. Although there was marked plasmocytosis in each of the reported cases, reactive plasmocytosis is likely to be mild in the majority of cases; for example, in a case series by Jego et al. only 2 out of 10 patients had a plasma cell washout >20% at [23].

Pathophysiology

In reactive plasma cell proliferations, there is a mixture of plasma cell precursors (plasmablasts) and precursors (early plasma cells), all of which have homogeneous CD45bright expression, whereas in normal bone marrow as well as plasma cell myeloma, there is heterogeneous CD45 expression [24]. The exact mechanism leading to proliferation is not known, but increased cytokine release seems likely as a cause, especially since IL-2 and IL-10 are strong stimuli for the formation of plasmablasts and early plasma cells [25]. IL-6 enhances this effect and is essential for plasma cell survival[25,26].

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is histologically characterized by a polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate and is more frequently associated with elevated serum cytokine levels (including IL-6 as well as IL-10) compared with other peripheral T-cell lymphomas. This observation suggests that in these cases the associated reactive plasma cell proliferation is cytokine-mediated. There are isolated cases described in the literature in which monoclonal plasma cell proliferation has also been noted [13,27,28].

Take-Home-Messages

- Reactive plasmocytosis is rare, but can be pronounced (plasma cell washout >20%).

- In the case of plasmocytosis, differentiation between reactive (polyclonal) and monoclonal plasma cell proliferation is possible rapidly and reliably by flow cytometric immunophenotyping from peripheral blood.

- Differential diagnosis focuses on infections, malignancies (especially hematologic tumors), and autoimmune diseases.

- The exact pathomechanism is unclear; increased cytokine release (IL-2, IL-6, IL-10) as a cause is possible.

Literature:

- Peterson LC, Kueck B Fau-Arthur DC, Arthur Dc Fau-Dedeker K, et al.: Systemic polyclonal immunoblastic proliferations.

- Li L, et al.: Polyclonal plasma cell proliferation with marked hypergammaglobulinemia and multiple autoantibodies. Ann Clin Lab Sci 36, 479–484 (2006).

- Gupta M, et al.: Etiological Profile of Plasmacytosis on Bone Marrow Aspirates. Dicle Medical Journal 43, 4, doi: 10.5798/diclemedj.0921.2016.01.0628 (2016).

- Batdorf B, Kroft S, Olteanu H, Harrington A: Reactive Bone Marrow Plasmacytosis: An Update for the Modern Era. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 142, A102-A102, doi: 10.1093/ajcp/142.suppl1.102 %J American Journal of Clinical Pathology (2014).

- Shtalrid M, Shvidel L, Vorst E: Polyclonal Reactive Peripheral Blood Plasmacytosis Mimicking Plasma Cell Leukemia in a Patient with Staphylococcal Sepsis. Leukemia & lymphoma 44, 379–380, doi: 10.1080/1042819021000029713 (2003).

- Ahsanuddin AN, Brynes RK, Li S: Peripheral blood polyclonal plasmacytosis mimicking plasma cell leukemia in patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 4, 416–420 (2011).

- Desborough MJ, Grech H: Epstein-Barr virus-driven bone marrow aplasia and plasmacytosis mimicking a plasma cell neoplasm. Br J Haematol 165, 272, doi: 10.1111/bjh.12721 (2014).

- Lee J, Chang Je Fau-Cho YJ, Cho Yj Fau-Han, et al.: case of reactive plasmacytosis mimicking multiple myeloma in a patient with primary Sjogren’s syndrome.

- Sokol K, et al.: Extreme Peripheral Blood Plasmacytosis Mimicking Plasma Cell Leukemia as a Presenting Feature of Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell Lymphoma (AITL). Front Oncol 9, 509, doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00509 (2019).

- Zhang J, et al.: Reactive plasmacytosis mimicking multiple myeloma associated with SFTS virus infection: a report of two cases and literature review. BMC Infect Dis 18, 528, doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3431-z (2018).

- SH S, et al.: WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press, Lyon WHO Classification of Tumours, Revised 4th Edition, Volume 2 (2017).

- J., B. B., Karl-Anton K: Das Blutbild – Diagnostische Methoden und klinische Interpretation. De Gruyter (2017).

- Xu J. et al.: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with coexisting plasma cell myeloma: a case report and review of the literature. Tohoku J Exp Med 235, 283-288, doi: 10.1620/tjem.235.283 (2015).

- Pellat-Deceunynck C, et al.: Reactive plasmacytoses, a model for studying the biology of human plasma cell progenitors and precursors. The hematology journal: the official journal of the European Haematology Association / EHA 1, 362–366, doi: 10.1038/sj/thj/6200053 (2000).

- Zamarin D, et al.: Polyclonal immune activation and marrow plasmacytosis in multiple myeloma patients receiving long-term lenalidomide therapy: incidence and prognostic significance. Leukemia 27, 2422–2424, doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.126 (2013).

- Wada T, et al.: Reactive peripheral blood plasmacytosis in a patient with acute hepatitis A.

- Koduri PR, Naides SJ: Transient blood plasmacytosis in parvovirus B19 infection: a report of two cases. Ann Hematol 72, 49-51, doi: 10.1007/bf00663017 (1996).

- Thai KT, et al: High incidence of peripheral blood plasmacytosis in patients with dengue virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 17, 1823-1828, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03434.x (2011).

- Wada T, Iwata Y, Kamikawa Y, et al: Peripheral Blood Plasmacytosis in Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome. Jpn J Infect Dis 70, 470-471, doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2016.575 (2017).

- Moon Y, et al: Klebsiella pneumoniae associated extreme plasmacytosis. Infect Chemother 45, 435-440, doi:10.3947/ic.2013.45.4.435 (2013).

- Sakai H, et al.: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma initially presenting with replacement of bone marrow and peripheral plasmacytosis. Intern Med 46, 419–424, doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6121 (2007).

- Yamane A, Awaya N, Shimizu T, et al.: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells in peripheral blood and marrow. Acta Haematol 117, 74–77, doi: 10.1159/000096894 (2007).

- Jego G, et al: Reactive plasmacytoses are expansions of plasmablasts retaining the capacity to differentiate into plasma cells.

- Pellat-Deceunynck C, Bataille R: Normal and malignant human plasma cells: proliferation, differentiation, and expansions in relation to CD45 expression. Blood Cells Mol Dis 32, 293-301, doi:10.1016/j.bcmd.2003.12.001 (2004).

- Jego G, Bataille R, Pellat-Deceunynck C: Interleukin-6 is a growth factor for nonmalignant human plasmablasts. Blood 97, 1817–1822, doi:10.1182/blood.v97.6.1817 (2001).

- Jourdan M, et al: IL-6 supports the generation of human long-lived plasma cells in combination with either APRIL or stromal cell-soluble factors. Leukemia 28, 1647-1656, doi:10.1038/leu.2014.61 (2014).

- Dogan A, Attygalle AD, Kyriakou C: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 121, 681–691, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04335.x (2003).

- Yi JH, Ryu KJ, Ko YH, et al.: Profiles of serum cytokines and their clinical implications in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Cytokine 113, 371–379, doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.10.009 (2019).

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2023; 11(6): 6–10