Chronic subdural hematomas are a common neurological disorder that occurs mainly in older people. The most commonly used therapeutic procedure is the burr hole craniotomy, but two other surgical procedures are also available. The incidence, treatment and therapeutic outcomes of chronic subdural hematomas in the Schwiez region were evaluated as part of a multicenter study. The study was published in the journal Frontiers in Neurology in 2023.

Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) is a spontaneous or post-traumatic serous fluid collection with portions of blood between the dura mater and arachnoid and mainly affects older people. The incidence varies greatly depending on the population and time period studied [1–3]. In connection with demographic trends, an increase in the prevalence of chronic subdural hematomas (cSDH) can be assumed [3–5]. In addition, the increasing use of oral anticoagulation has increased the incidence of cSDH [6].

The following surgical therapy methods are available for the treatment of cSDH:

- Borehole craniotomy: Borehole craniotomy is the most commonly used procedure and is considered by most neurosurgeons to be the gold standard in the treatment of cSDH [7,8]. According to studies, there is no consensus on the number of drill holes [7]. Once the drill holes have been made, the dura is incised and the hematoma capsule is opened so that the hematoma contents can drain away; a drain can then be inserted. Liu et al. in their meta-analysis, which also included other treatment methods such as burr hole craniotomy, found a reduction in the recurrence rate of up to 60% when a drain was inserted, without an increase in complications or mortality [9].

- Twist Drill Trepanation: This procedure can be performed either with the application of a closed drainage system or, as with the bedside percutaneous subdural tapping (BPST) method, by spontaneous drainage of the hematoma contents [7]. In both methods, the procedure is performed under local anesthesia.

- Craniotomy: Craniotomy is the oldest surgical procedure.

Putnam and Cushing recommended this procedure as early as 1925 [10].

Nowadays, it is rarely used due to its high invasiveness and high complication rate in cSDH [7].

A multicentre national cohort study was conducted to obtain an overview of the hospitalization rates, treatment and therapeutic outcomes of cSDH in Switzerland [11].

cSDH patients in the age range of 67-83 years

Included were 663 patients from 15 treatment centers (Box) who required surgical treatment for cSDH [11]. Almost all of the patients were referred via emergency medical services. The median age was 76 years (IQR 67-83 years). 34.4% (n=228) were women with a median age of 77 years (IQR 69-83 years) and 65.6% (n=435) were men with a median age of 75 years (IQR 67-83 years). The female:male sex ratio was 1:1.9. The overall incidence rate of cSDH was 8.2:100,000.

| Neurosurgical centers of the following hospitals participated in the study: Hospital Sion, Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, Cantonal Hospital Winterthur, University Hospital Zurich, Hirslanden Clinic Zurich Cantonal Hospital Aargau, University Hospital Basel, Inselspital Bern, University Hospital Geneva, Cantonal Hospital Graubünden, University Hospital Lausanne, Lucerne Cantonal Hospital, Clinic St. Anna Lucerne, Cantonal Hospital Lugano |

| to [11] |

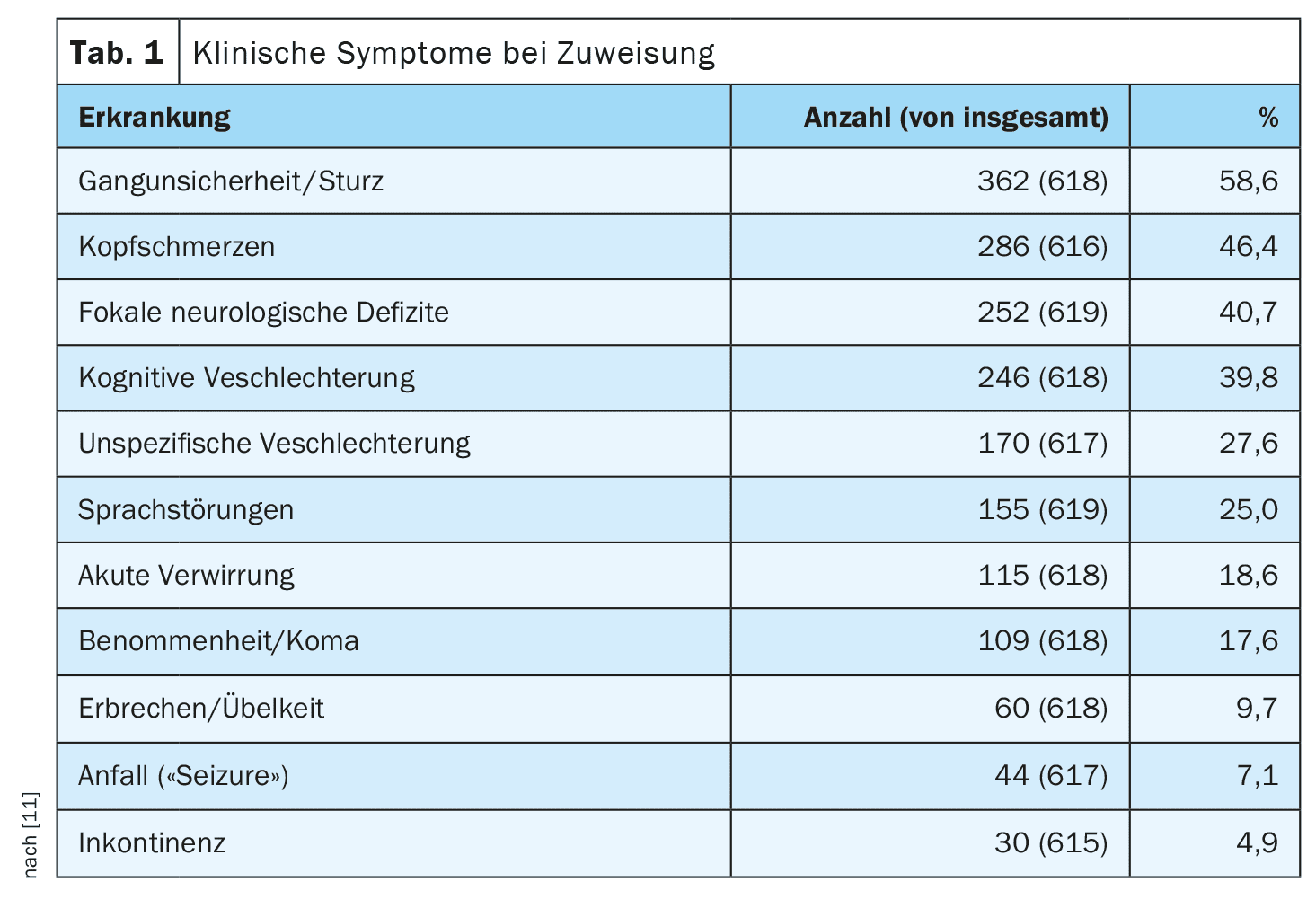

In addition to the medical history, including a medication history regarding anticoagulants and platelet inhibitors, the imaging was evaluated on admission. The most common symptoms were (Tab. 1) [11]:

- Gait disturbances (58.6%),

- Headaches (46.4%),

- Focal neurological deficits (40.7%)

The distribution of cSDH was unilateral in 72.1% (n=478) patients, while 185 patients had bilateral hematoma, with no difference in outcome.

Evaluation of the therapy results

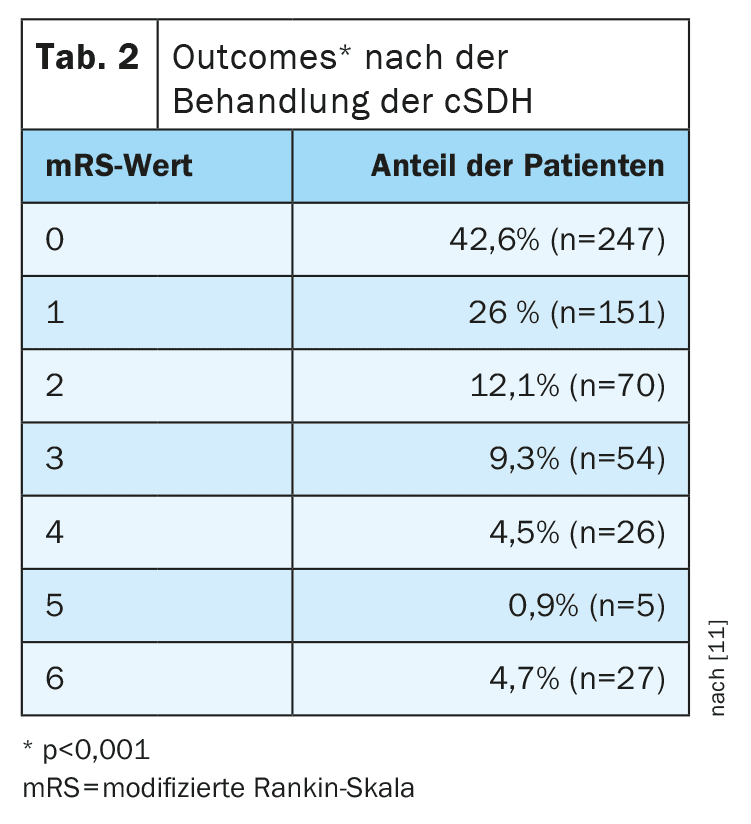

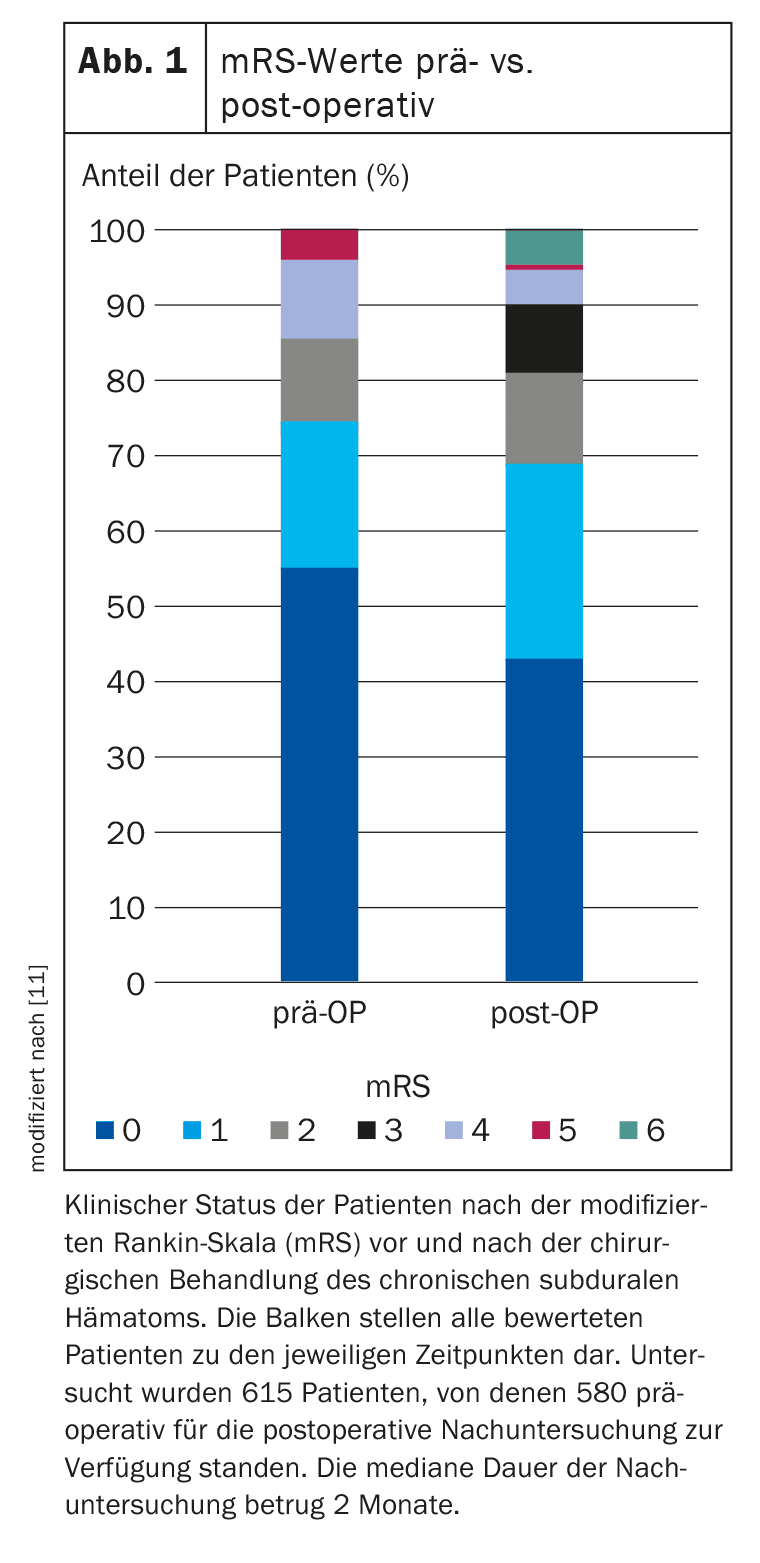

If left untreated, cSDFH carries a high risk of mortality due to the rapid increase in intracranial pressure. The therapeutic procedures evaluated in the study were categorized as bore hole craniotomy (BHC), twist drill trephination (TDC) and craniotomy. The outcome was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) during the outpatient clinical visit 1 to 6 months after surgical treatment of cSDH [11]. The mRS indicates the patient’s degree of impairment or loss of function. The scale ranges from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death). The outcomes were dichotomized into good (mRS, 0-3) and poor (mRS, 4-6) outcomes. A two-tailed t-test was performed for unpaired variables, while a chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The recurrence rate was defined as the need for reoperation and the time of recurrence was assessed in weeks after the primary operation and complications. In addition, clinical parameters associated with poor outcomes and recurrence were identified. The most important results at a glance:

BHC was the most commonly performed procedure at 97.3% (n=758), of which 21.9% of cases were 1-hole BHC and 87.1% were 2-hole BHC. Craniotomy was performed in 20 patients (2.6%) and TDC in one patient. Subdural drains were inserted in 33.2% (n=261) and subgaleal drains in 57.2% (452). In 43 cases no drains were inserted.

The outcomes after treatment of cSDH differed significantly compared to the preoperative situation (p<0.001) (Tab. 2, Fig. 1) . The median time of outcome assessment was 2 months (IQR 1-6 months) postoperatively.

A good outcome was observed in almost 81% of patients. A recurrence of cSDH after a median of 2 weeks (IQR 1-4 weeks) was observed in 20.1% (n=104). A second recurrence occurred in 17 patients (2.6%) at a median of 3 weeks (IQR 1-10) after surgical drainage of the first recurrence. The mortality rate was 4%. Factors associated with poorer outcome included older age, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and mRS on admission, and the presence of multiple deficits at the time of cSDH diagnosis. Factors that did not show a significant association with poor outcomes were midline shift, gender, use of antiplatelet agents or oral anticoagulation, unilateral or bilateral cSDH, or the side of cSDH.

Literature:

- El Rahal A, et al: Incidence, therapy, and outcome in the management of chronic subdural hematoma in Switzerland: a population-based multicenter cohort study. Front Neurol. 2023 Sep 14; 14: 1206996.

- Asghar M, et al: Chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly – a North Wales experience. J R Soc Med 2002; 95(6): 290-292.

- Kudo H, et al: Chronic subdural hematoma in elderly people: present status on Awaji Island and epidemiological prospect. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1992; 32(4): 207-209.

- Kolias AG, et al: Chronic subdural haematoma: modern management and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurol 2014; 10(10): 570-578.

- Ducruet AF, et al: The surgical management of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Rev 2012; 35(2): 155-169; discussion 169.

- Kinsella K, Velkoff VA: Aging World: 2001. International Population Reports. Govt Reports Announcements & Index (GRA&I) 2001, Issue 07, www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-08/AgingWorld2001_0.pdf,(last accessed 27.06.2024)

- Cartmill M, et al: Prothrombin complex concentrate for oral anticoagulant reversal in neurosurgical emergencies. Br J Neurosurg 2000; 14(5): 458-461.

- “Bedside borehole trephination as a therapy for subacute and chronic subdural hematoma”, Inaugural dissertation, Raphaela von Dechend, 2017, https://ediss.uni-goettingen.de,(last accessed 27.06.2024)

- Almenawer SA, et al: Chronic subdural hematoma management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34,829 patients. Ann Surg 2014; 259 (3): 449-457.

- Liu W, Bakker NA, Groen RJM: Chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review and metaanalysis of surgical procedures. J Neurosurg 2014; 121 (3): 665-673.

- Putnam TJ, Cushing H: Chronic subdural hematoma: its pathology, its relation to pachymenigitis hermorrhagica and its surgical treatment. Arch Surg 1925; 11: 329-393.

FAMILY PHYSICIAN PRACTICE 2024; 19(7): 34-35