The consensus recommendations of the international Vitiligo Task Force were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology in 2023. Corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors are still the first choice for topical therapies. The topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib was approved as a new agent in the EU last year. Phototherapy remains an important treatment modality and can be combined with topical and some systemic agents. For certain forms of vitiligo, surgical intervention may be advisable.

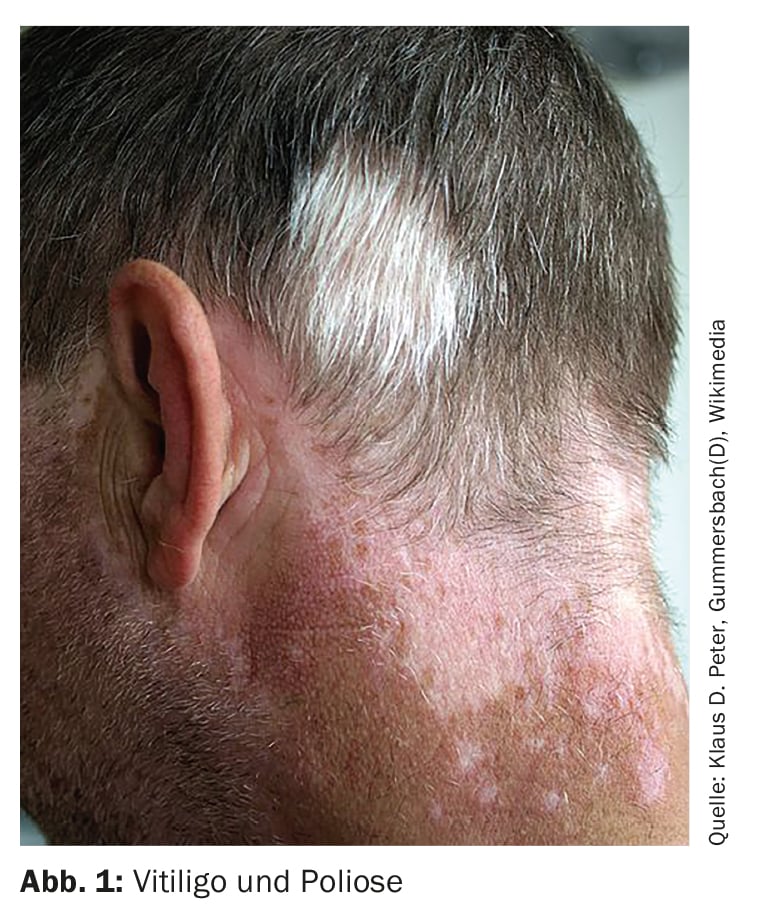

Vitiligo is an acquired, circumscribed or universal hypomelanosis [1,2]. It is a complex disease in which various mechanisms are involved. Clinically characteristic are sharply defined, white macules that affect the skin and mucous membranes in varying degrees of spread and severity, depending on the subtype of vitiligo (Fig. 1 ). According to the classical classification, a distinction is made between non-segmental and segmental vitiligo as well as mixed and unclassifiable forms [2]. The diagnosis is usually made clinically; Wood’s light can be used to better visualize vitiligo spots in patients with light skin types. A biopsy for differential diagnosis (box) is useful in individual cases [2].

| Differential diagnosis The most important differential diagnoses of vitiligo are progressive macular hypomelanosis, hypomelanosis guttata idiopathica and post-inflammatory hypopigmentation (leukoderma). Leukoderma can occur in the context of numerous infectious, acute or chronic inflammatory skin diseases (e.g. leprosy, pityriasis versicolor, burns, circumscribed scleroderma, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus), but also as a side effect of certain physical or drug treatments. Vitiligo must also be differentiated from hypomelanosis Ito, nevus depigmentosus, piebaldism and Klein-Waardenburg syndrome, which are among the circumscribed, congenital hypomelanoses. |

| according to [2] |

Topical treatment – classics and newcomers

In order to achieve sustainable treatment results, a proactive treatment strategy is required, according to a key statement in the position paper [1]. The main goals of therapy are to achieve a cosmetically flawless skin appearance and to alleviate psychological suffering. Vitiligo can be very stressful in everyday life due to the visible skin symptoms.

Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are particularly recommended for vitiligo patients with limited infestation and extrafacial localizations. TCS appears to be more effective for stabilizing vitiligo than for repigmentation, although there is no clear evidence on this, according to the Task Force [1,3]. The best results in terms of repigmentation can be achieved on the face and neck. For adults and children with limited infestation, once daily application of potent TCS is recommended. In children, TCS are considered safe if they are used continuously for no longer than 2-4 months; in adults, a duration of use of 3-6 months has been best studied [3].

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI): In adults and children with limited infestation, especially for lesions on the face and neck or in skin folds (e.g. axillary, inguinal), TCIs are considered the first choice. The efficacy of TCS and TCI appears to be similar, although TCI may be slightly less effective in extrafacial lesions [4,5]. The topical safety profile of TCI is better compared to potent TCS, particularly with regard to the risk of skin atrophy, according to the Task Force [1]. The use of TCI is particularly useful in areas where prolonged use of potent TCS is contraindicated. Twice daily application of TCI is recommended [6]. Treatment should initially be prescribed for 6 months. If it proves to be effective, a longer duration of therapy (e.g. up to 12 months or longer) may be suggested. TCIs are generally also suitable for younger patients. For optimal repigmentation, the combination of TCI with UV light therapy can be considered. Clinical studies in vitiligo patients have not shown a significant association between the use of TCI and systemic immunosuppression, skin infections or an increased risk of skin cancer and other malignancies (including lymphoma) [7].

The topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib was approved in the EU last year based on the results of the placebo-controlled phase III studies TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 [8].

Topical or systemic Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are currently the greatest hope for vitiligo. Ruxolitinib has not yet been approved in Switzerland (as of 31.01.2024). A total of 674 patients were included in the two randomized-controlled, double-blind phase III studies TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 [8]. Response rates were significantly better than with placebo: 50.3% and 74.6% of patients achieved a facial VASI (F-VASI) of 75 and 50, respectively, at week 52. In addition, 51.1% of patients achieved a total VASI (T-VASI) of 50 at week 52. The rate of treatment-related adverse events was 13.7% in participants treated with ruxolitinib cream. The most common adverse events were acne at the application site (4.4%) and itching (3.5%).

Phototherapies: an important pillar of therapy

Various phototherapeutic procedures are an important treatment modality for vitiligo that has been established for decades. However, a high level of patient compliance is required to achieve good treatment results.

Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) is recommended as first-line therapy for extensive or rapidly progressing disease and for whole-body treatment. Phototherapy has been used in children as young as 3 years of age [9]. To limit the risk of cumulative exposure in children and adults, it is recommended to discontinue phototherapy if there is no improvement after 3 months or if the results are not satisfactory after 6 months of treatment [1]. Erythema and xerosis are the most frequently reported acute adverse effects of NB-UVB therapy. However, there does not appear to be a significant correlation between NB-UVB therapy and basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma or melanoma.

Excimer lasers (308 nm) are primarily recommended for patients with limited vitiligo. [10]. Excimer lamps are more common than excimer lasers [1]. Its wavelength is also 308 nm, but it is not strictly collimated and monochromatic, and is also less energy-rich [2]. Both therapies appear to be on a par in terms of repigmentation efficiency. Since excimer therapy does not treat the entire skin, but only the vitiligo foci with light and a lower cumulative dose in the treatment area is sufficient to achieve the same result, the use of excimer lamps and lasers appears to be safer in terms of potential side effects. The combination with topical and systemic active ingredients (e.g. TCS, TCI) appears to enhance the effect of targeted light therapy. Acute undesirable side effects include erythema and blistering.

Photochemotherapy: The use of oral psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy is not recommended, but topical PUVA or topical PUVA phototherapy (PUVA SOL) can be used to treat localized lesions; these approaches can avoid systemic complications associated with oral psoralen, such as gastrointestinal discomfort [1]. Erythema and phototoxicity of the skin are the most common side effects associated with the use of topical PUVA or PUVA-SOL therapy [11]. Whether there is an association between these treatment methods and an increased risk of skin cancer has not yet been conclusively clarified.

Home-based phototherapy: Light therapy that can be carried out at home has the advantage that patients do not have to visit a treatment center several times. The disadvantages include a small selection of devices, high acquisition costs and the need for maintenance [1]. Otherwise, phototherapy in the home setting is associated with better compliance, similar repigmentation results and comparable side effect rates. However, patient satisfaction is significantly higher with phototherapy carried out in the practice.

| Recommendations for combination therapies For optimal repigmentation, the combination of TCI with UV light therapy can be considered (taking safety aspects into account) |

| Combined with UV light therapy, oral mini-pulse therapy with cortisone (oral mini-pulse, OMP) can achieve a higher degree of repigmentation (consider the risk-benefit profile of long-term treatment with steroids) |

| The use of systemic steroids (prednisolone 20 mg/day or 0.3 mg per kg body weight/day in children) for 3 weeks in combination with excimer laser and TCI has also been shown to be beneficial in early segmental vitiligo. |

| Antioxidant agents can be used in combination with phototherapy to achieve better stabilization and repigmentation of vitiligo lesions. |

| The combined use of phototherapy with immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, ciclosporin and azathioprine has not yet been investigated. |

| according to [1] |

Systemic active ingredients – what’s new?

In cases of extensive vitiligo, rapid progression and insufficient response to topical preparations or UV therapy, the use of systemic pharmacotherapy may be considered.

Systemic JAK inhibitors are promising and their use could be considered if necessary, according to the Task Force [1]. Ritlecitinib was investigated in various doses in Phase II studies [12]. Biologics such as anti-TNF-α and anti-interleukin-17 are currently not recommended for vitiligo.

According to the position paper, conventional immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, ciclosporin or azathioprine can be used for progressive vitiligo, but there is a lack of conclusive evidence of efficacy and safety [1].

Oral cortisone minipulse therapy (oral minipulse, OMP) with betamethasone 5 mg or dexamethasone 2.5-5 mg twice a week on two consecutive days per week can be considered for the treatment of rapidly progressive vitiligo [1]. A treatment period of up to 3 months is recommended; a longer period should not exceed 6 months in order to avoid the risk of undesirable effects. OMP therapy in combination with UV light therapy can lead to greater repigmentation, but safety aspects must be taken into account. It is important to inform patients appropriately. Side effect risks can be minimized by intermittent, low-dose therapy.

Antioxidant agents such as vitamin E, vitamin C, resveratrol, ubiquinone, alpha-lipoic acid, pantothenic acid or ginkgo biloba have been used alone or in combination with phototherapy to achieve stabilization and repigmentation of vitiligo lesions, but the evidence base is very heterogeneous and there is currently no clear consensus on this, according to the Task Force [1].

Surgical interventions and therapies for depigmentation

If the condition of segmental or focal vitiligo is stable over time and other treatment options have failed, surgery may be an option [1]. Criteria for the choice of technique include the localization of the skin change as well as the expertise and equipment.

Depigmentation therapy should only be considered for subtotal vitiligo in patients with dark skin types and high levels of suffering [13]. Topical depigmenting treatments include hydroquinone monobenzyl ether, 4-methoxyphenol and phenol [1].

Cryotherapy and pigment lasers are options for physical depigmentation [1]. The Q-switched ruby laser (QSR) is more suitable for patients with lighter skin types, and the Q-switched alexandrite laser has a faster pulse rate than the QSR, which may allow for better tissue penetration. According to the position paper, the Nd:YAG laser can be used at a wavelength of 532 nm to treat epidermal pigments [1].

Literature:

- Seneschal J, et al: Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: Position statement from the international Vitiligo Task Force-Part 2: Specific treatment recommendations JEADV 2023; 37(11): 2185-2195.

- Böhm M, et al: S1 guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of vitiligo. JDDG 2022; 20(3): 365-379.

- Thomas KS, et al: Randomized controlled trial of topical corticosteroid and home-based narrowband ultraviolet B for active and limited vitiligo: results of the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184(5): 828-839.

- Lepe V, et al: A double-blind randomized trial of 0.1% tacrolimus vs 0.05% clobetasol for the treatment of childhood vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139(5): 581-585.

- Köse O, Arca E, Kurumlu Z: Mometasone cream versus pimecrolimus cream for the treatment of childhood localized vitiligo. J Dermatolog Treat 2010; 21(3): 133-139.

- Radakovic-Fijan S, et al: Oral dexamethasone pulse treatment for vitiligo. JAAD 2001; 44(5): 814-817.

- Ju HJ, et al: The long-term risk of lymphoma and skin cancer did not increase after topical calcineurin inhibitor use and phototherapy in a cohort of 25,694 patients with vitiligo. JAAD 2021; 84(6): 1619-1627.

- Rosmarin D, et al: Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. NEJM 2022; 387(16): 1445-1455.

- Picardo M, et al: Vitiligo. Nat Rev Dis Primer 2015; 1: 15011

- Rodrigues M, et al; Vitiligo Working Group. Current and emerging treatments for vitiligo. JAAD 2017; 77(1): 17-29.

- Esmat S, et al: Phototherapy and combination therapies for vitiligo. Dermatol Clin 2017; 35(2): 171-192.

- Ezzedine K, et al: Efficacy and safety of oral ritlecitinib for the treatment of active nonsegmental vitiligo: A randomized phase 2b clinical trial. JAAD 2023; 88(2): 395-403.

- AlGhamdi K, Kumar A: Depigmentation therapies for normal skin in vitiligo universalis. JEADV 2011; 25: 749-757.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 34(1): 46-47