A thorough clarification of the cause of epileptic seizures is essential for a therapeutic decision. The large number of available preparations allows an individual therapy for the affected person. The risk of recurrence is a critical factor in the decision to treat early.

Pharmacotherapy has been the basis of epilepsy treatment since the discovery of the first effective seizure medications. All currently available substances have a purely symptomatic seizure suppressive effect and do not influence the underlying pathophysiology, which is why we should speak of anticonvulsive and not antiepileptic medication. However, since not all epileptic seizures are “convulsive” – i.e., with muscle twitching – the term anticonvulsant is not entirely accurate. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposes that substances used to treat epileptic seizures be referred to as “seizure medication” [1].

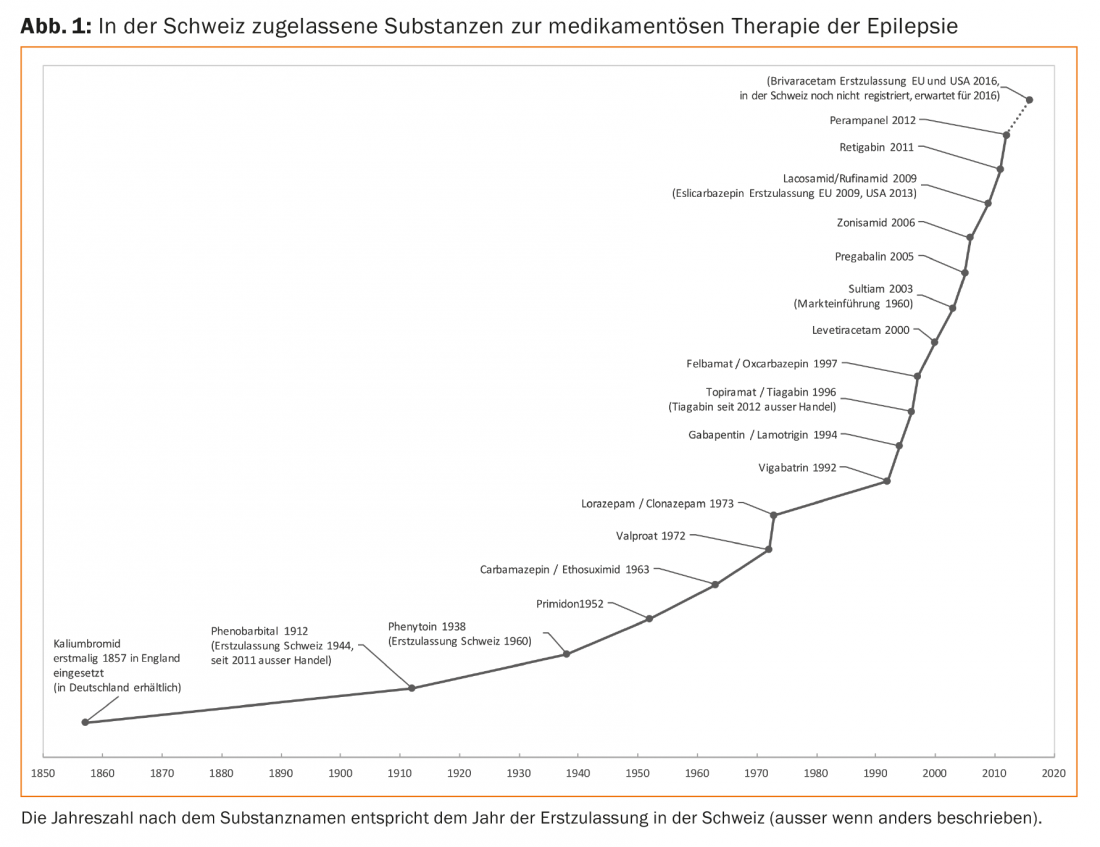

In addition to the older standard substances still in use, such as phenytoin, primidone, carbamazepine, ethosuximide and valproic acid, other substances are available (Fig. 1). By now, some of these new seizure medications have been in use for a long time, so their advantages and disadvantages are well known.

Treatment already after the first unprovoked seizure?

A thorough clarification of the cause of epileptic seizures is essential for a therapeutic decision. According to the latest epilepsy classification of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), the diagnosis of epilepsy can already be made after a first unprovoked seizure if, according to corresponding clarification results, there is a recurrence risk for a further seizure of at least 60% in ten years and the recurrence risk is thus similar to that after two unprovoked seizures.

If there is a high risk of recurrence, anticonvulsant therapy can be initiated even after a first unprovoked seizure, according to international guidelines such as those of the German Society of Neurology. Overall, however, it is usually an individual therapy decision that also takes into account the patient’s attitude to medication, fear of side effects and also the patient’s (and relatives’) need for safety or willingness to take risks [2].

Two large multicenter studies (FIRST – First Seizure Trail Group; MESS – Multicentre Epilepsy and Single Seizure Study) examined the risk of recurrence and long-term prognosis with immediate vs. delayed seizure treatment [3–6]. In both studies, immediate treatment after a first unprovoked seizure was shown to reduce the risk of a recurrence by 50% and 30%, respectively; however, half of the study participants did not have a second seizure. Early treatment initiation had no effect on seizure frequency after three and five years, respectively, in either study.

According to the data of the MESS study, the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent a further epileptic seizure is 14 after a first seizure and 5 after a second epileptic seizure. The long-term prognosis of therapy does not deteriorate if a possible second epileptic seizure is awaited [4,5].

Overall, many studies have shown that the risk of recurrence is highest shortly after the first seizure. 80-90% of patients who develop further seizures suffer the relapse within the first two years. However, the currently available study results are often difficult to apply to today’s clinical practice, since, for example, structural imaging was not performed in all study participants in the MESS trial. This is now required by guidelines and is also common practice, as structural cerebral lesions lead to an increased risk of recurrence and may therefore be cause for early anticonvulsant therapy [7–9].

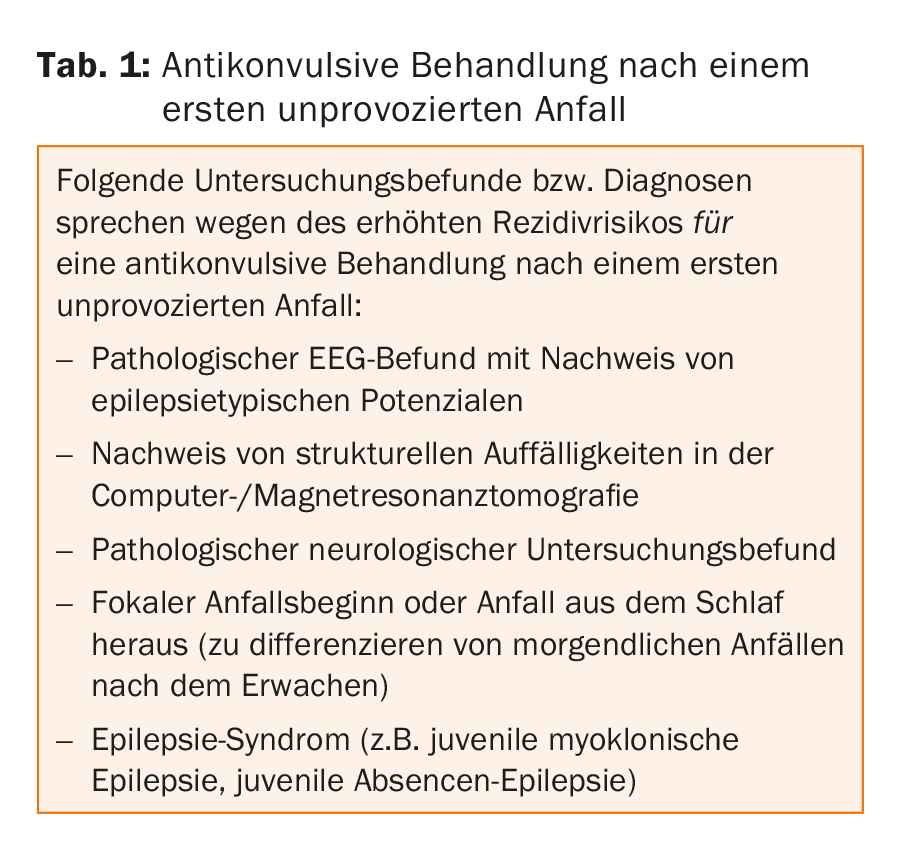

However, current studies do not allow a general recommendation whether anticonvulsive therapy is already indicated after the first epileptic seizure. However, there are examination findings resp. Diagnoses that must be assumed to be at increased risk of recurrence and therefore give rise to earlier pharmacotherapy (Table 1).

Initial anticonvulsant therapy

In general, it is recommended to start with a monotherapy and to dose it out first. Choosing a drug for initial therapy is not easy with the variety of drugs available. However, there are certain criteria that must be considered in the selection process: Seizure type, epilepsy syndrome classification, gender, concomitant diseases, concomitant medication, and urgency of treatment. Overall, approximately 60-70% of adult patients become seizure-free with the first anticonvulsant medication administered. When choosing a substance, the tolerability and the influence of comorbidities should also be taken into account, since about 60% of patients have to take the medication for seizure control for the rest of their lives.

According to the guidelines, all anticonvulsant drugs are suitable for initial monotherapy in focal epilepsies except ethosuximide, which is used only for absences (petit mal seizures).

Lamotrigine and levetiracetam have been shown to be equally effective; they are preferred to carbamazepine because of better tolerability [10]. Levetiracetam, in particular, is frequently used in routine clinical practice because it does not require long dosing, it does not induce enzymes, and it results in fewer interactions with other drugs. Levetiracetam and lamotrigine usually hardly provoke seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGE), this in contrast to e.g. carbamazepine. In the recent large randomized controlled SANAD (Standard And New Antiepileptic Drugs) trial, lamotrigine was superior to carbamazepine, gabapentin, and topiramate in terms of time to treatment discontinuation and nontolerable side effects in focal epilepsies (Arm A) [11]. In another study, pregabalin was shown to be less effective when compared directly with lamotrigine [12].

Suitable agents for initial monotherapy of generalized or unclassified epilepsy include valproate, lamotrigine, and topiramate, which were compared in arm B of the SANAD trial [13]. Valproate showed better efficacy compared with lamotrigine and better tolerability compared with topiramate. To achieve seizure freedom of one year, topiramate was comparable to valproate.

Treatment of women of childbearing age

Reliable contraception is indicated for anticonvulsant-treated women of childbearing age. Attention must be paid to clinically relevant interactions of contraceptives with seizure medications (e.g., with lamotrigine), as both contraceptives may attenuate the effect of seizure medications and vice versa. For most of the newer substances, there are currently insufficient data to allow a definitive assessment of a possible effect on the unborn child. In a large registry study, women treated with seizure medications during pregnancy were found to have a very low risk of major congenital malformations of only 4.2% (2-4% malformation rate in the normal population) [14]. No increased risk of serious birth defects with use of a newer seizure medication during pregnancy was shown in a Danish study [15]. In a study published in 2014, topiramate was associated with possible higher growth retardation in the unborn child [16].

Valproate should be used with great caution in women of childbearing age. Reasons include teratogenic risk and adverse effect on long-term cognitive development of children exposed to valproate in utero [17]. Based on current data, the recommendation is to use valproate only when absolutely necessary and then in a sustained-release form and as low a dose as possible, preferably less than 1000 mg/d.

Further treatment after unsuccessful initial treatment

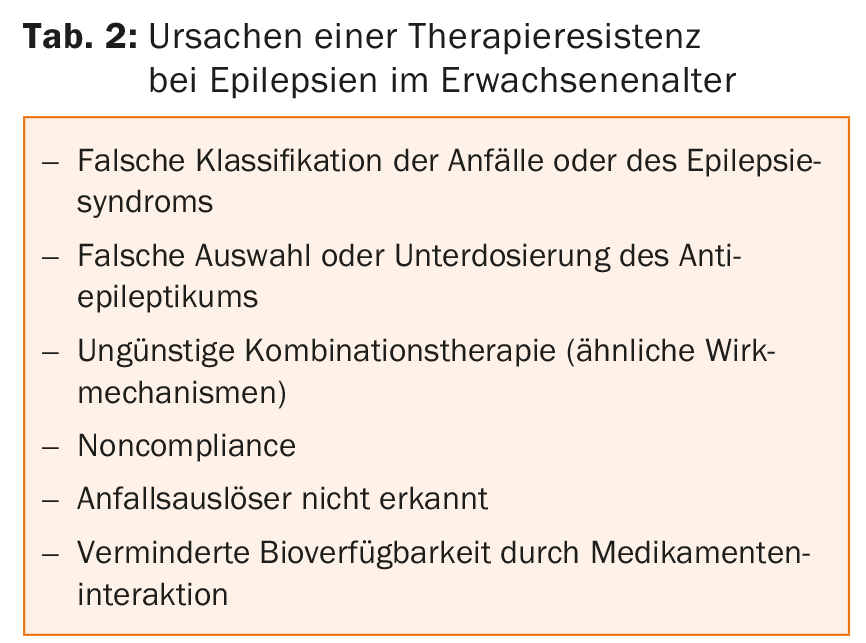

Pharmacoresistance occurs when sustained seizure freedom is not achieved after adequate treatment trials with two tolerated, appropriate antiepileptic drugs applied at sufficiently high doses (either as monotherapy or in combination). Then the diagnosis of epilepsy should be critically re-examined, e.g. with 24h video-EEG, and differential diagnoses should also be sought. Early consideration should also be given to possible epilepsy surgery. Possible causes of treatment resistance are listed in Table 2.

In principle, all approved substances are conceivable for a combination treatment. Caution is advised with concomitant administration of sodium channel blockers as this may result in more severe central nervous system side effects. The newly approved substances for combination therapy, some of which have a different mechanism of action, such as lacosamide, rufinamide, retigabine and perampanel, give rise to the hope that in individual cases freedom from seizures can still be achieved through synergistic and additive effects in the case of pharmacoresistance.

Use of generics

Initial therapy can easily be given with a generic preparation. Generic drugs can also be used or substituted for epilepsy that has not yet been successfully treated. Because of variable bioavailability and a consequent increased risk of seizure, switching from the originator drug to the generic drug, from the generic drug to the originator drug, or even from one generic drug to another in seizure-free patients should be rejected [18].

Termination of therapy

Little reliable data exist on the question of medication discontinuation when seizure-free for many years. Clinical practice is to continue medication unless serious side effects occur. Stopping is recommended only when the seizure-triggering situation is no longer present. In addition, some forms of childhood and adolescent epilepsy can “grow out”. Before the therapy is stopped, the patient must be informed about the possible consequences of stopping the therapy.

Literature:

- Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding – Institute of Medicine [Internet], 2012. www.iom.edu/epilepsy

- Elger CE: First epileptic seizure and epilepsies in adulthood – What’s new ? The most important recommendations at a glance. Definition and classification 2016; 1-23.

- First Seizure Trial Group (FIR.S.T. Group): Randomized clinical trial on the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs in reducing the risk of relapse after a first unprovoked tonic-clonic seizure. Neurology 1993; 43(3 Pt 1): 478-483.

- Musicco M, et al: Treatment of first tonic-clonic seizure does not improve the prognosis of epilepsy. First Seizure Trial Group. Neurology 1997; 49(4): 991-998.

- Marson A, et al: Immediate versus deferred antiepileptic drug treatment for early epilepsy and single seizures: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 365(9476): 2007-2013.

- Kim LG, et al: Prediction of risk of seizure recurrence after a single seizure and early epilepsy: Further results from the MESS trial. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5(4): 317-322.

- Eickhoff SB, et al: Anatomical and functional connectivity of cytoarchitectonic areas within the human parietal operculum. J Neurosci 2010; 30(18): 6409-6421.

- Hauser W, et al: Seizure recurrence after a 1st unprovoked seizure: an extended follow-up. Neurology 1990; 40(8): 1163-1170.

- Krumholz A, et al: Evidence-based guideline: Management of an unprovoked first seizure in adults: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2015 Oct; 85(17): 1526-1527.

- Rosenow F, et al: The LaLiMo Trial: lamotrigine compared with levetiracetam in the initial 26 weeks of monotherapy for focal and generalised epilepsy – an open-label, prospective, randomised controlled multicenter study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83(11): 1093-1098.

- Marson AG, et al: The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369(9566): 1000-1015.

- Kwan P, et al: Efficacy and safety of pregabalin versus lamotrigine in patients with newly diagnosed partial seizures: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, parallel-group trial. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10(10): 881-890.

- Marson AG, et al: The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalised and unclassifiable epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369(9566): 1016-1026.

- Morrow J, et al: Malformation risks of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy: a prospective study from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77(2): 193-198.

- Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Hviid A: Newer-generation antiepileptic drugs and the risk of major birth defects. JAMA 2011; 305(19): 1996-2002.

- Veiby G, et al: Fetal growth restriction and birth defects with newer and older antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. J Neurol 2014; 261(3): 579-588.

- Meador KJ, et al: Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12(3): 244-252.

- Rueegg S, et al: Use of generic antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy therapy – statement of the Swiss League against Epilepsy (SLgE). Swiss Arch of Neurol and Psychiatr 2012; 163(3): 104-106.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(3): 8-11.