Both most patients and many doctors are uncomfortable with surgical procedures on the nail because they fear – not without good reason – pain and postoperative dystrophy. There are a number of things that can be done to counter these fears, as the following article impressively explains.

To ensure that surgical procedures on the nails run smoothly for everyone involved, the following points should be observed:

- Effective and long acting anesthesia

- Least possible traumatization

- Preoperative diagnosis as accurate as possible

- Knowledge of various surgical techniques

- Refrain from pointless interventions.

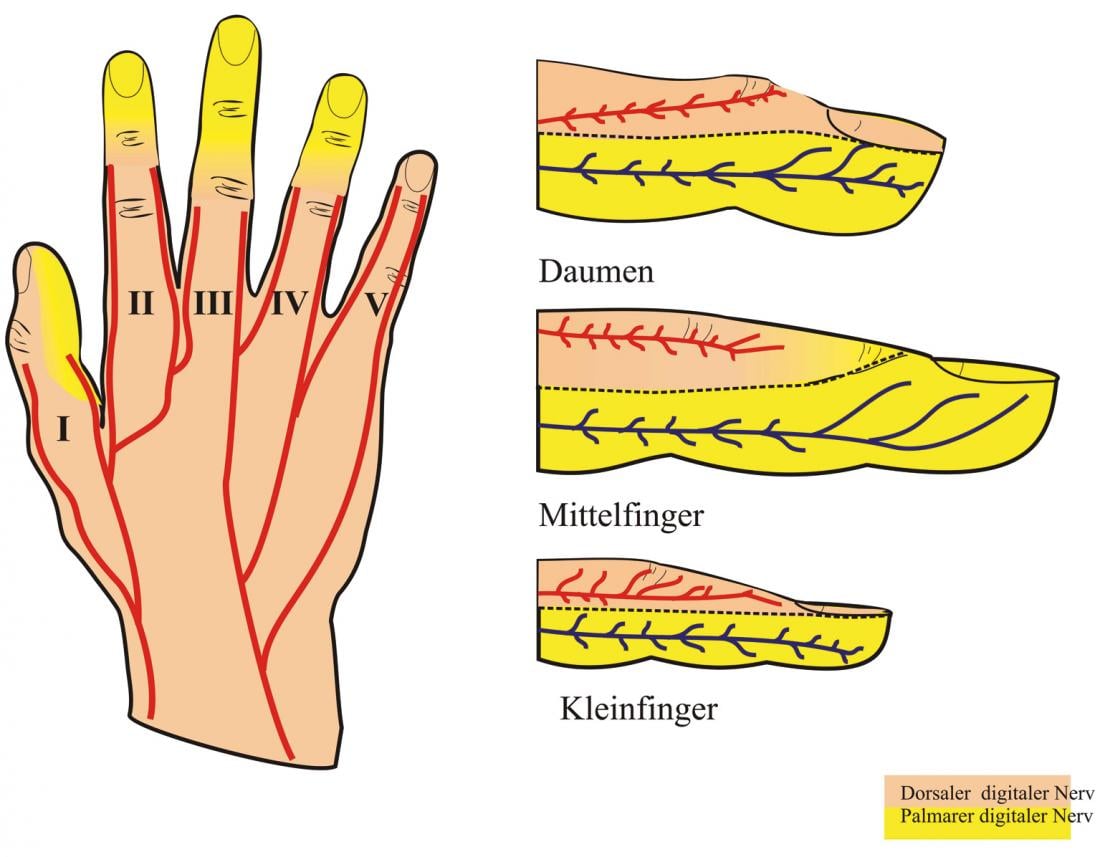

Innervation of the fingernails

The surgically relevant innervation of the fingernails is variable. The thumb nail and little finger nail are covered by the dorsal nn. digitales proprii, while those of the index, middle and ring fingers are supplied by the volar finger nerves (Fig. 1) . This is the basis for the effectiveness of the transthecal block. The flexor tendons of the fingers are flat ligaments, the visual sheaths extend far laterally, and from them the local anesthetic diffuses rapidly to the nerves.

Fig. 1 Innervation of the fingernails

Anesthesia Techniques

The most commonly used technique is Oberst’s conduction anesthesia. It can be used to anesthetize the entire finger or toe, and the injection points are far from the nail, so there is no risk of spreading infection. For the injection we use a cannula No. 28 or No. 30, which makes the sting hardly painful.

The metacarpal block anesthetizes the opposite sides of adjacent fingers or toes, making it suitable for multiple nail surgery.

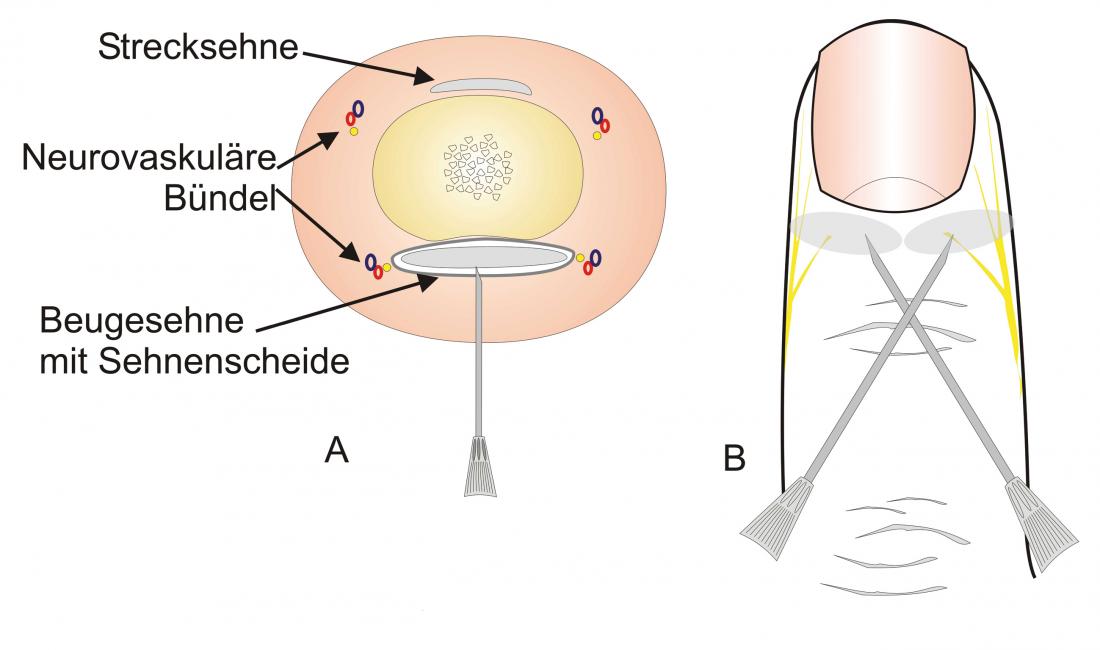

The transthecal block is suitable for the index, middle and ring finger nails because they are innervated by the nervi digitales proprii volares. A No. 30 cannula is used in the volar crease of the metacarpophalangeal joint. To prevent the anesthetic from escaping into the palm, pressure is applied to the tendon sheath proximal to the injection point with the index finger of the other hand. Anesthesia of the distal half of the finger is thus achieved within a few minutes. The transthecal block has the advantage of requiring only one injection point and not injuring the neurovascular bundles as in Oberst’s conduction anesthesia (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Anesthesias

A: Transthecal block from the palmar groove of the metacarpophalangeal joint.

B: Distal fan block with injection point the distal interphalangeal joint.

Distal digital anesthesia is preferred by some authors because it is said to have a faster onset of action. In personal experience, this is not the case. In addition, there is very little loose tissue here, so that the injection volume is what is actually painful. In case of infections, distal injection close to the nail is contraindicated.

Local anesthetics

Most local anesthetics such as lidocaine, prilocaine, mepivacaine, bupivacaine, or ropivacaine can be used for nail surgery.

In our experience, most nail surgeries are painful once the anesthesia wears off. Therefore, a long-acting local anesthetic is useful. Lidocaine 2% has a longer effect than lidocaine 1%. Our best experience has been with 1% ropivacaine, whose onset of action is almost as rapid as that of lidocaine or mepivacaine, but which acts for eight to twelve hours, sometimes longer. The addition of epinephrine 1:100 000 or 1:200 000 is contraindicated only in cases of evident distal circulatory impairment. However, it is not necessary in most nail surgeries because a tourniquet is applied anyway.

Tourniquet

There are several ways to apply a finger or toe tourniquet. The simplest is a rubber tube, which is placed with two tours around the base of the base phalanx and fixed with a small vessel clamp. There are also metal bands, which are tightened by means of a screw. Their advantage is that they are wider than a rubber tube and can be tightened or loosened during surgery.

For fingernail surgery, we use a sterile surgical glove that is placed over the patient’s disinfected hand. A very small hole is cut in the appropriate fingertip and the fingerling is then pulled over the fingertip and rolled to proximal, creating a virtually complete blood void, whereas the usual tourniquets only cause a tourniquet. The glove tourniquet also ensures an absolutely sterile environment.

Tourniquets should not be left on fingers and toes for more than 20-30 minutes; for longer operations, it is recommended to open it briefly every 20 minutes.

Minimally invasive nail surgery

The nail apparatus is an extremely sensitive organ. If possible, the nail plate should be preserved, because then the postoperative pain is less and the healing is better and faster. If the nail is not part of the pathology to be removed, it is placed back on the matrix and nail bed at the end of the surgery and fixed with one or two stitches. Of course, the nail must not then be infected or colonized with bacteria.

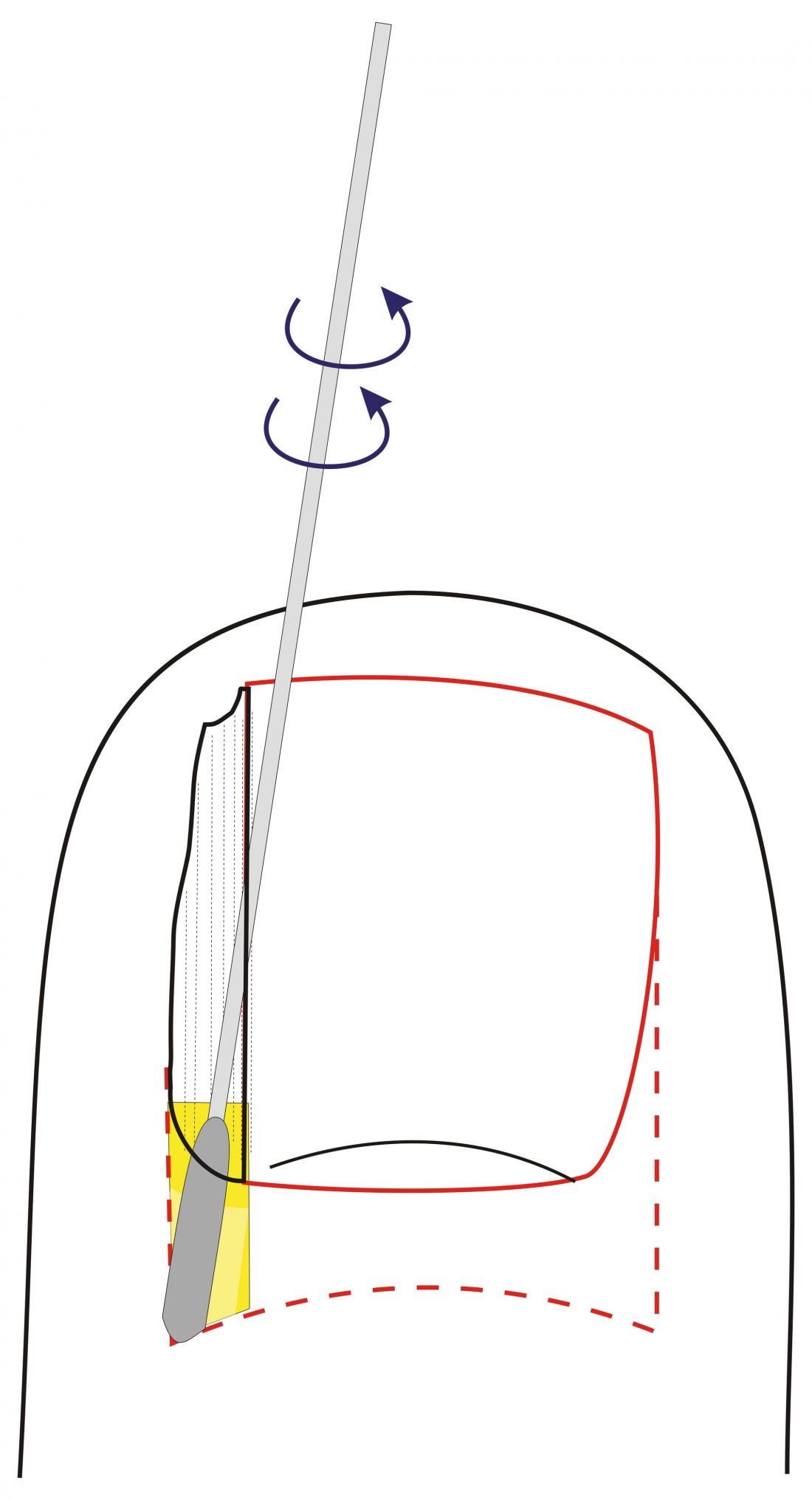

Minimally invasive nail extraction

Nail extraction is one of the most severe iatrogenic nail traumas. In most cases, it is not indicated. However, if it is necessary, it is only the beginning of a therapy and cannot be recommended as the sole measure. Above all, it should be noted that no nail extraction will result in a better nail. A traumatized nail is much more susceptible to fungal infections.

The technique still described in some books, in which a coarse vascular clamp is first pushed under the proximal nail wall, then under the nail plate, the nail is grasped and torn out by turning the clamp, is extremely traumatizing and damages the sensitive nail bed.

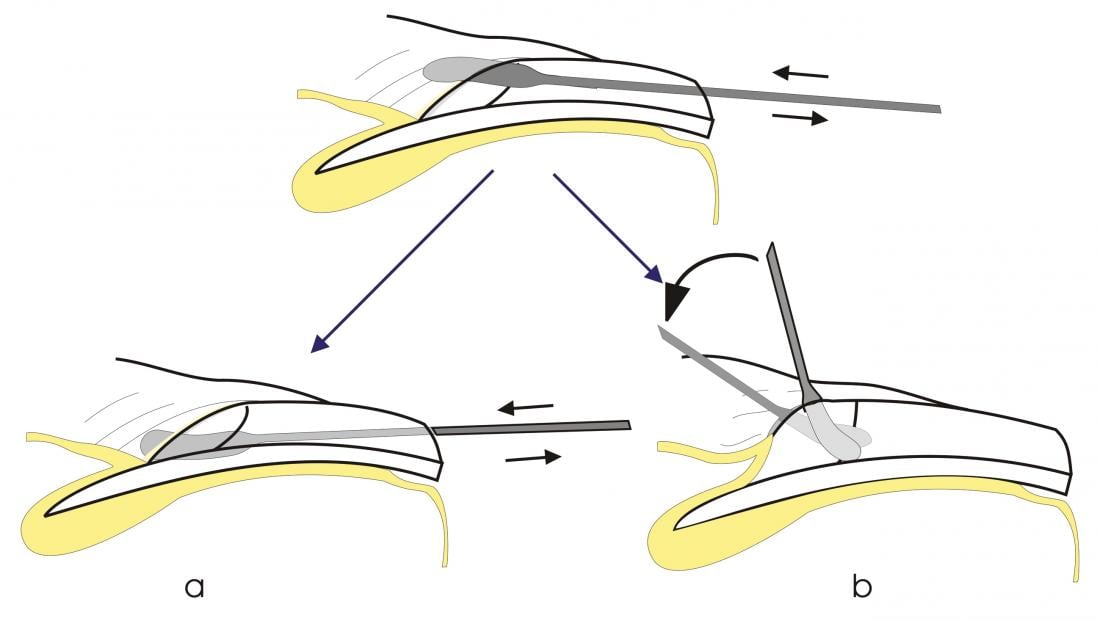

The nail is carefully detached from the proximal nail wall and the nail bed using an elevator. In the distal method, the elevator is then guided under the nail via the hyponychium, with the tip always pointing upwards towards the nail plate. From the center, the nail is completely separated by moving the elevator back and forth from side to side. In the proximal method, the elevator is passed around the proximal end of the nail after separation from the proximal nail wall and the nail is separated from the matrix and nail bed from the proximal side. These two techniques are much less traumatic, healing is faster, and postoperative pain is significantly less (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Minimally invasive nail extraction

a: Distal method

b: Proximal method

Minimally invasive nail biopsy

Different techniques are available for different parts of the nail.

Minimally invasive nail plate biopsy: Histological examination of the nail plate material very often allows the diagnosis of onychomycosis, often psoriasis, some other diseases can be excluded. For this purpose, nail is cut taking with it as much as possible subungual keratin. In principle, a PAS stain should be requested.

Minimally invasive nail bed biopsy: The nail bed is characterized by a unique structure of rete ridges that run parallel longitudinally. Therefore, the nail bed biopsy should also always be performed in the longitudinal axis of the nail, so that the longitudinally arranged reteleists and capillaries of the nail bed are injured as little as possible. Superficial tangential biopsies from the nail bed are often very informative.

Lateral longitudinal nail biopsy: It is the best biopsy technique for the diagnosis of all long standing nail lesions and allows information over several months of disease progression. It is also suitable for removal of laterally localized tumors and correction of wide nails. With the racket nail, it is performed on both sides.

The lateral longitudinal nail biopsy contains the proximal nail wall, matrix, nail bed and hyponychium. Postbiopsy nail deformation is minimal if the biopsy is

- is not wider than 2 mm

- the lateral nail wall remains intact

- and back stitches lift the lateral nail wall.

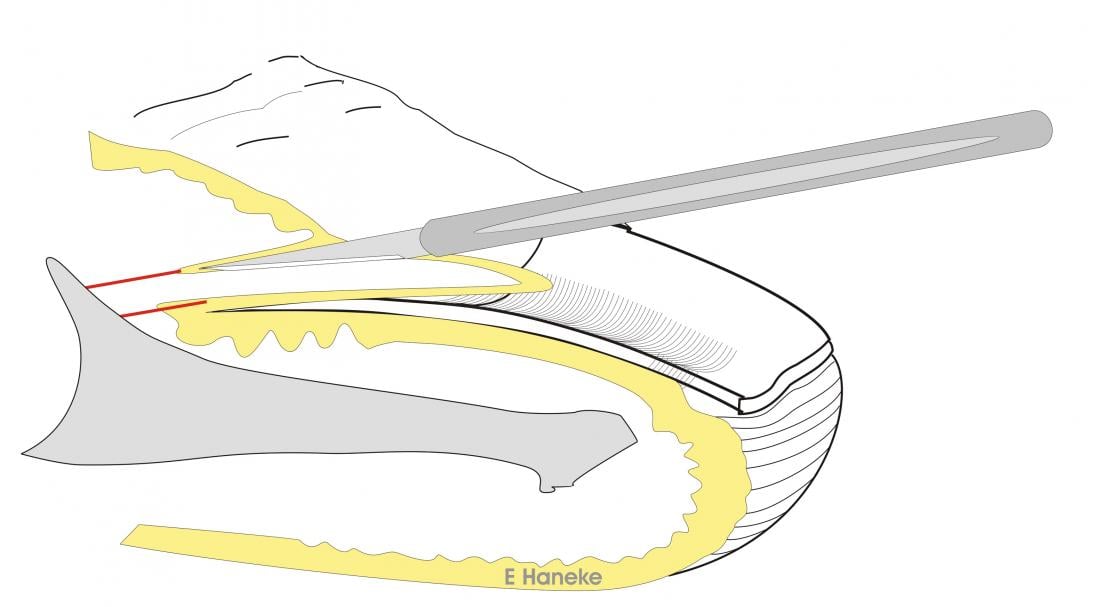

Minimally invasive matrix biopsy: Nail matrix biopsies must always be transverse to the direction of nail growth and preferably parallel to the distal lunate border. In this way, a postbiopsy split nail can be avoided. Tangential or horizontal biopsy is suitable for superficial pigmentary changes. Depending on the location of the change to be biopsied, the proximal nail wall is either retracted only or, after detaching the underlying nail plate, incised on both sides and folded back. The nail is then carefully detached from the matrix as in proximal nail extraction, but only to the extent of remaining a maximum of 3-5 mm distal to the pigment foci. Here, the nail is incised from one side and opened like a trap door (Fig. 4) . This reveals the melanocyte focus, which is usually larger than the width of the pigment strip would suggest. It is always larger in the longitudinal axis than transversely. Now, a shallow incision is made around the focal point with a safety margin of approximately 3 mm. Using sawing movements, a #15 scalpel held parallel to the matrix surface is used to tangentially remove the entire hearth in a thickness of approximately 0.7 to a maximum of 1 mm. The delicate tissue slice is spread out on filter paper and transferred to formalin. The unfolded nail section is put back and fixed with a stitch, alternatively a steristrip. Then the nail wall is sewn back. Wound healing is without complications and postbiopsy nail dystrophy. It is possible that the superficial epithelial layer of the matrix adhering to the nail plate is partly responsible for the rapid healing without complications. This technique allows excision of even large melanocyte foci.

Fig. 4: Minimally invasive matrix biospy

Minimally invasive nail wall biopsy: Depending on the change to be biopsied/excised, a superficial biopsy, a wedge-shaped or superficial biopsy at the proximal nail wall, a fusiform or superficial biopsy at the lateral nail wall can be performed. For larger excisions, a bridge flap is suitable to restore the lateral nail wall.

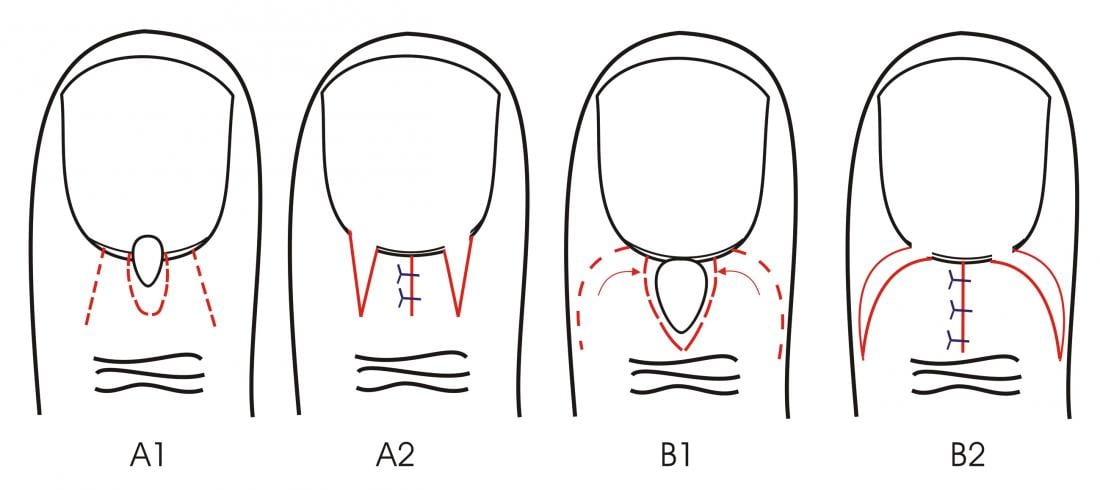

Removal of a tumor from the edge of the proximal nail wall

The proximal nail wall is a functionally and cosmetically important structure. Any defect or asymmetry is clearly visible. In addition, a nail that is not covered proximally by the dorsal nail wall becomes rough and loses its shine. The removal of a tumor is shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 5: Tumor removal

Flaps are formed from the nail wall next to the defect, which can be moved towards each other after detaching from the underlying nail and then easily sutured centrally. a) Narrow central defect; b) Larger defect closed by two small rotational flaps.

Minimally invasive surgery of the ingrown nail

In Switzerland, Kocher’s wedge excision, which was described by Kocher’s boss, the Bern surgeon Emmert, and which Kocher had advised against (!), is still the most frequently performed operation for the ingrown toenail. It has a recurrence rate of well over 25% and very commonly results in mutilation of the toe end phalanx. Consequences such as narrowing of the toe, nail crookedness, onycholysis and nail spurs are unfortunately the rule rather than the exception. The reason for this very poor record of wedge excision is the apparent lack of knowledge of the anatomy of the great toenail, especially its matrix, which extends far plantar-proximal and is very rarely removed during wedge excision. Therefore, the lateral matrix horn remains standing and gives rise to recurrences and nail spurs.

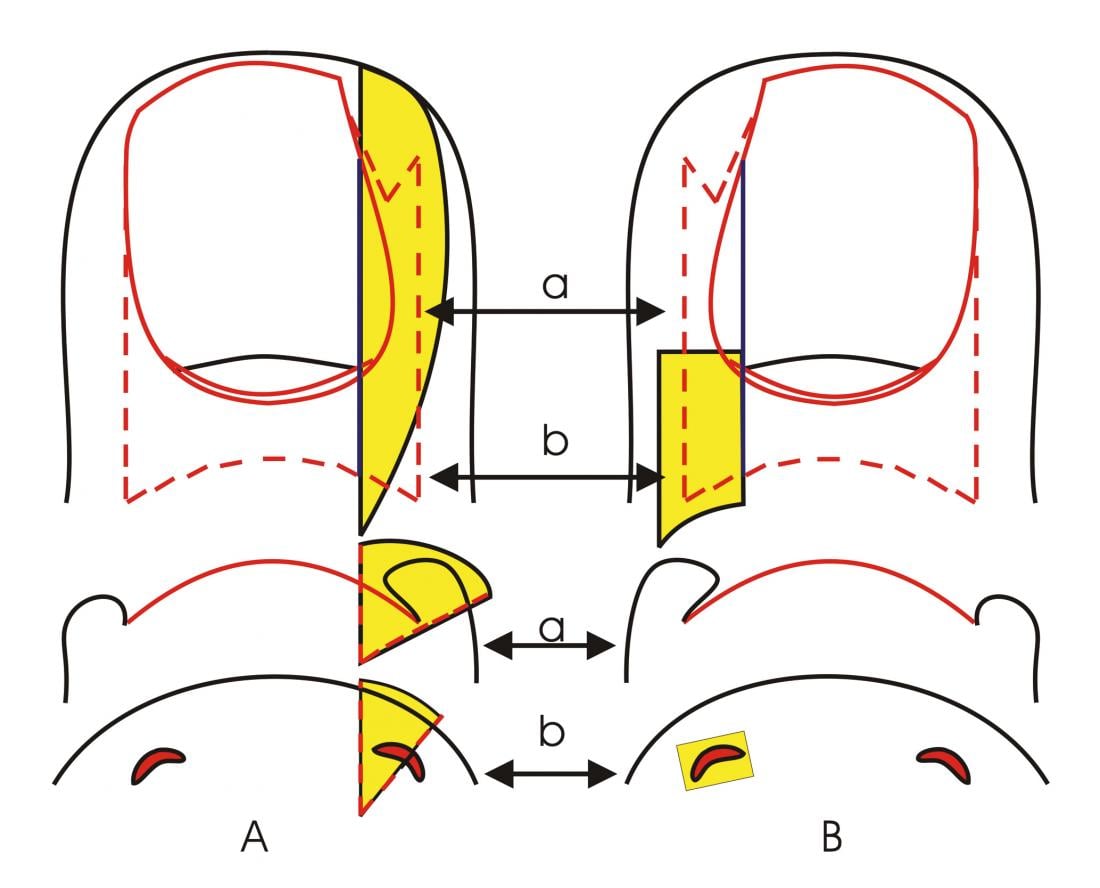

Two starting points exist for surgical therapy of unguis incarnatus: either the nail is too wide for the nail bed and the distal half of the distal phalanx, or the nail walls are hypertrophy. If one tends to the first assumption, it is logical to definitely narrow the nail, in the second one would result in the removal of the hypertrophic nail walls. This surgery is known as the Vandenbosch procedure and gives good results functionally and cosmetically, but has a very long recovery time of four to six weeks. We therefore prefer lateral segmental matrix horn removal (Fig. 6) instead of generous soft tissue excision.

Fig. 6 K. Keilexcision vs. matrix horn removal

Comparison of selective matrix horn removal with Kocher’s wedge excision for the treatment of ingrown big toenail.

A: Keilexcision

B: Selective matrix horn removal

a and b represent cross sections at the level of the proximal nail bed (a) and of the matrix horn (b) and show the size of the respective soft tissue excisates.

Under local or conduction anesthesia, the ingrown nail strip is removed by making a longitudinal incision in the side of the nail and pulling out the strip after detaching the nail bed, matrix, and underside of the proximal nail wall. Then dip a fine cotton swab in phenolum liquefactum (88-90% phenol) and rub the phenol vigorously into the small wound cavity created by nail strip removal while draining blood. Histological studies have shown that after four minutes of exposure, the matrix epithelium is completely cauterized. The tourniquet is then released and followed by a thick padded toe bandage with plenty of ointment. This is removed after 24 hours. Now the patient should rinse the foot twice a day under a strong stream of water to remove the secretion from the small wound cavity. Some grease ointment and a plaster are sufficient afterwards. Wound healing is completed after two to three weeks, but the patient can walk normally the day after surgery. The result is a slightly narrower, otherwise normal nail. The recurrence rate is less than 2%. Antibiotics do not need to be given. Postoperative pain is minimal because phenol has not only a strong disinfecting effect but also a local anesthetic effect.

Minimally invasive nail tumor surgery

Benign tumors should be removed as completely as possible, but without mutilation. Malignant tumors are excised either with Mohs surgery or with extensive reconstruction of the nail organ.

Ungual fibrokeratomas are relatively common fibroepithelial tumors that can arise anywhere within the nail organ. If they grow out of the nail pocket, their origin is generally in the dorsal or proximal matrix; the tumor presses on the matrix, creating a groove in the nail. The fibrokeratoma is then usually visible as a small dark spot under the cuticle.

If the site of origin is in the middle matrix, the tumor will grow partially intraungual before breaking through the nail. Here, too, you can then see a sharply punched groove distal from it. If a fibrokeratoma develops from the nail bed, a bulge develops.

The surgical technique is largely identical, with minor variations: a fine pointed scalpel is used to go parallel and along the fibrokeratome to the bone, and the scalpel is guided around the tumor to make a circular incision to the bone (Fig. 7) .

Fig. 7: Fibrokeratome removal

Removal of an ungual fibrokeratoma from deep within the nail pocket.

The incision is made around the distal tumor in depth to the bone.

Fine curved scissors can then be used to dissect the tumor off the bone. A seam is not required. A similar approach can be taken with Koenen’s tumors of tuberous sclerosis if there are not yet too many tumors.

Bowen’s disease and squamous epithelium are grouped by some authors under the name epidermoid carcinoma of the nail. They grow slowly and have a good prognosis. A generous local excision is sufficient. In Bowen’s disease, the visibly altered area is removed with a safe distance; the wound edges are checked microscopically. Depending on the size, the defect can be closed with a local flap or free graft, or the wound can be allowed to heal secondarily. In invasive squamous cell carcinoma, the excision must extend to the bone.

Melanomas are rather overrepresented on the nail, calculated on the overall small body surface. As long as one still has an intact nail without dystrophy, one can assume in the majority of cases a still very early melanoma – in situ or early invasive. Local excision of the nail organ has been shown to be superior to amputation. Again, the defect can be allowed to heal per secundam and closed with a graft or various flap plastics. Finger- and toe-preserving surgery significantly increases the acceptance of surgery.

Literature by the author

Prof. Dr. med. Eckart Haneke