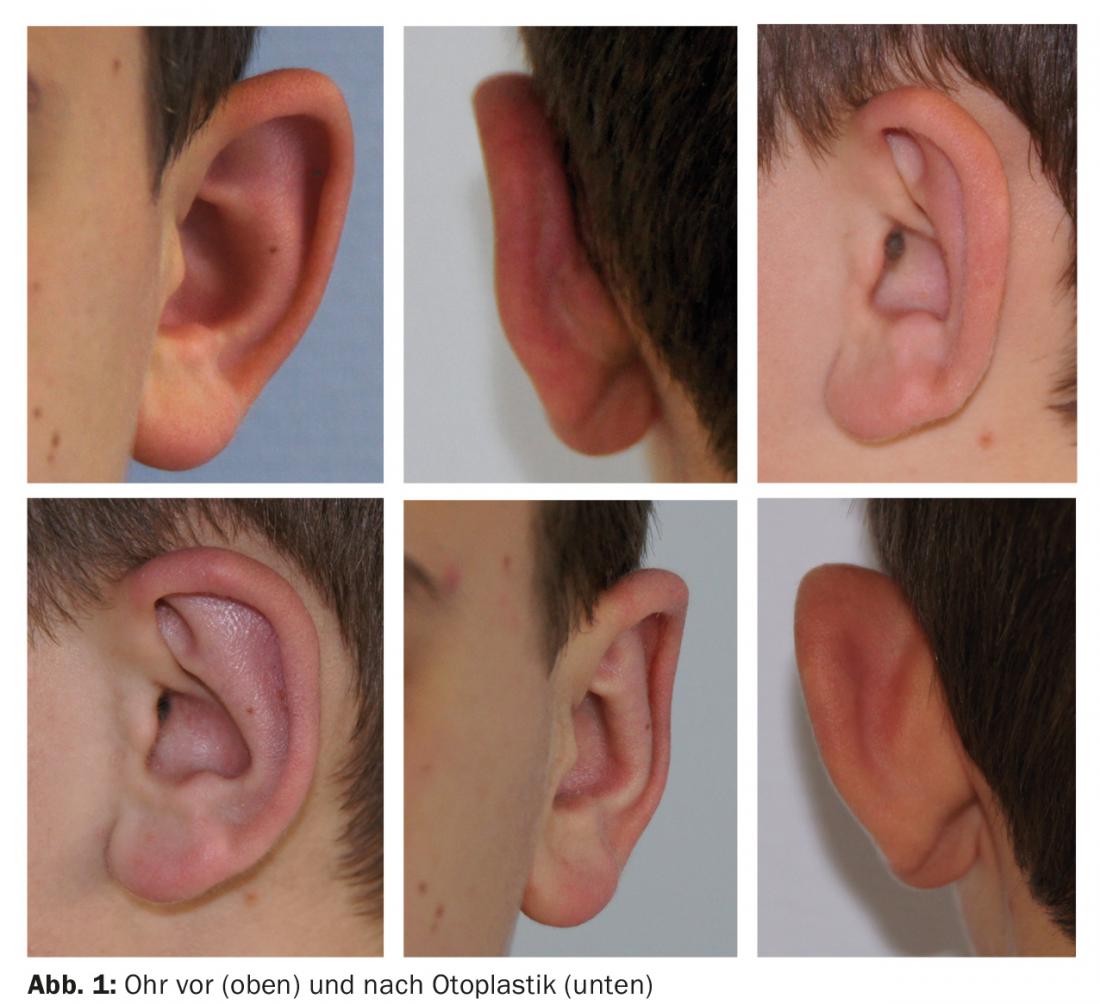

The protruding auricle is usually corrected surgically. Otoplasty is usually done before school enrollment to avoid teasing as much as possible, but it can also be done later. Otoplasty in skilled hands is a safe way to achieve an aesthetically pleasing pinna. Otoplasty is not a mandatory benefit of health insurance, but often a partial amount is covered.

Malformations of the auricle are common. Thus, in ENT, about 50% of all malformations affect the ear region. Approximately one in 6000 newborns has an ear malformation. While severe dysplasia occurs with a frequency of 1:10,000-20,000 [1], mild malformations and abnormalities of the auricle, which include protruding ears, are found in up to 5% [2]. Majority of malformations occur unilaterally (70-90%), with the right side more commonly affected (58-61%) [3].

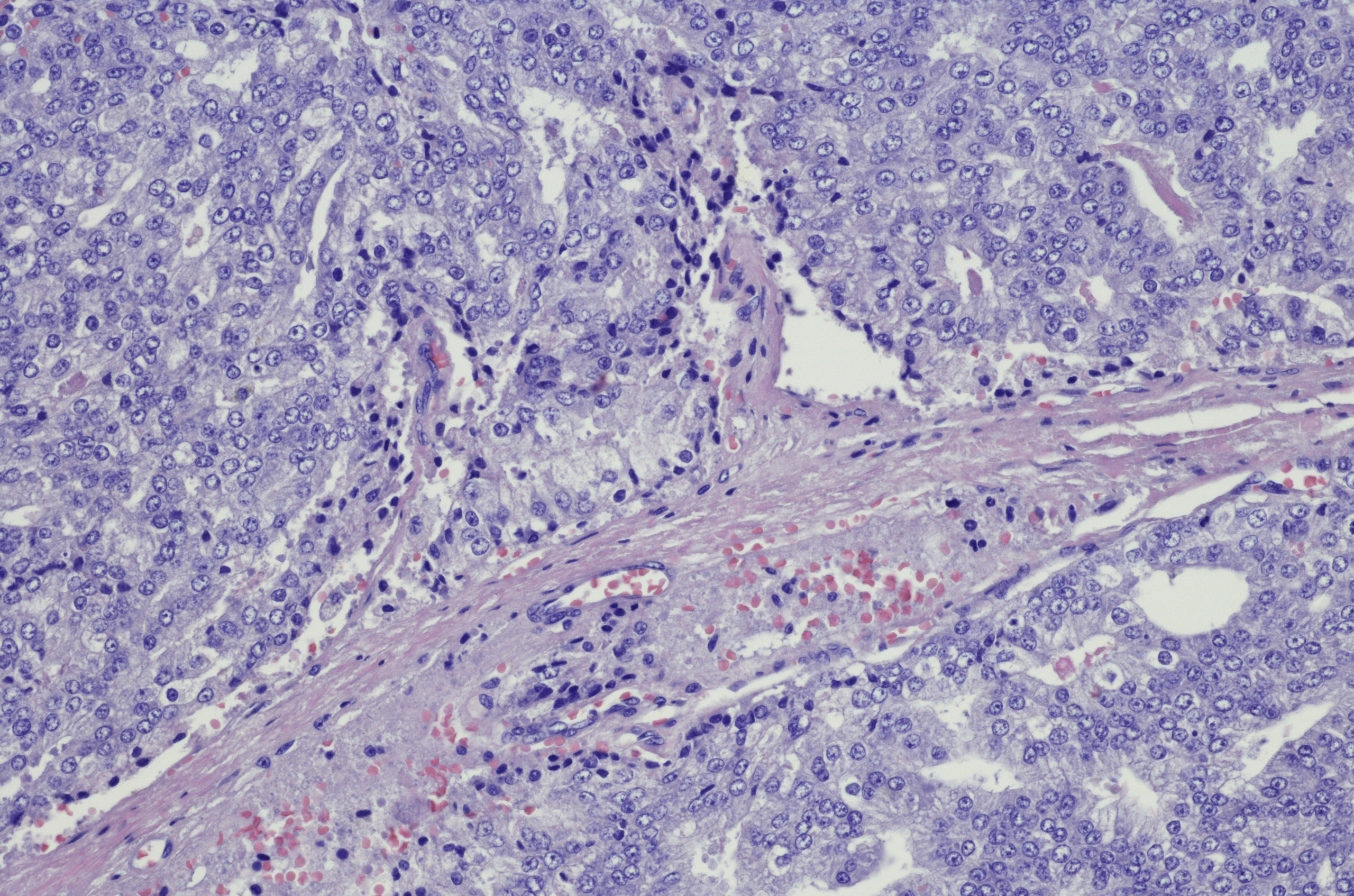

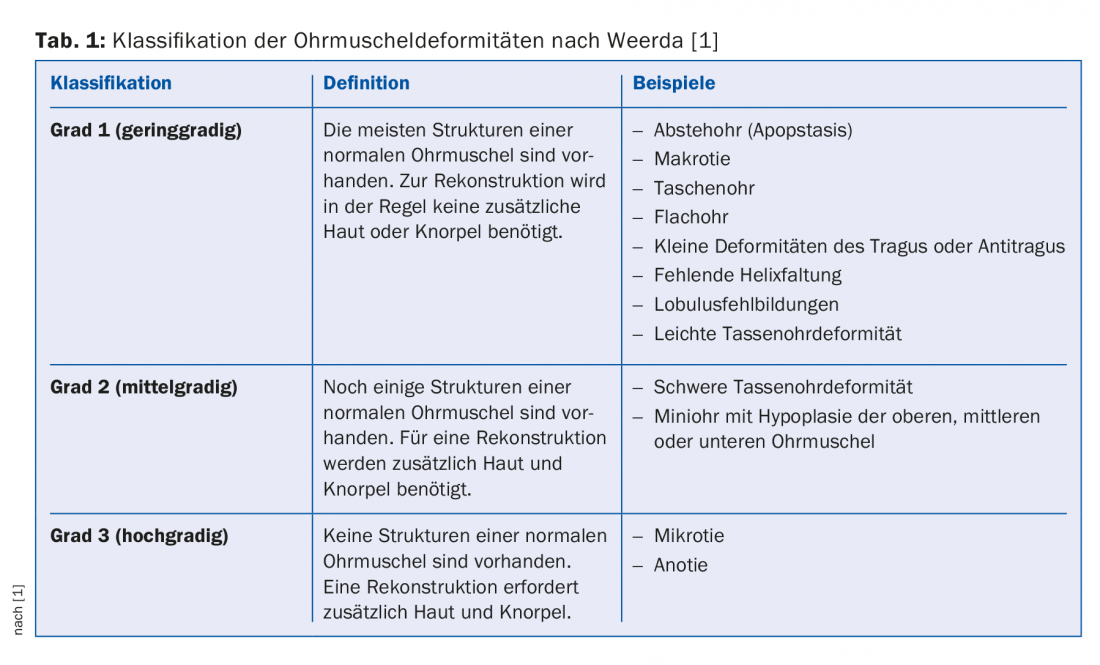

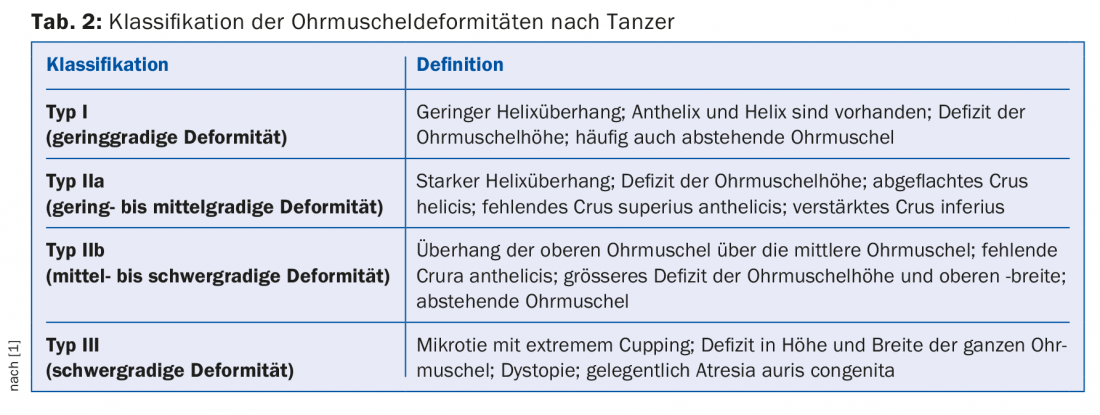

The nature and expression of auricular dysplasias are diverse. Auricular malformations are often classified according to Weerda (Tab. 1) . The malformations are subdivided according to increasing severity and the effort required for surgical intervention [1]. First-degree dysplasias are most common. In these mild deformities, most of the structures of a normal auricle are present, and reconstruction can usually be performed without additional skin or cartilage. Examples are the protruding ear, macrotia, lack of helix formation, or mild cup ear deficiencies (Tanzer I, IIa, and IIb) (Table 2) [1]. Grade 2 dysplasias include moderately severe deformities. Structures of a normal auricle are still present. However, additional skin and cartilage are needed for reconstruction. Representatives of this group are the heavy cup ear deformities or mini ears. In grade 3 dysplasias, no structures of a normal auricle are present, usually only a rudiment is found.

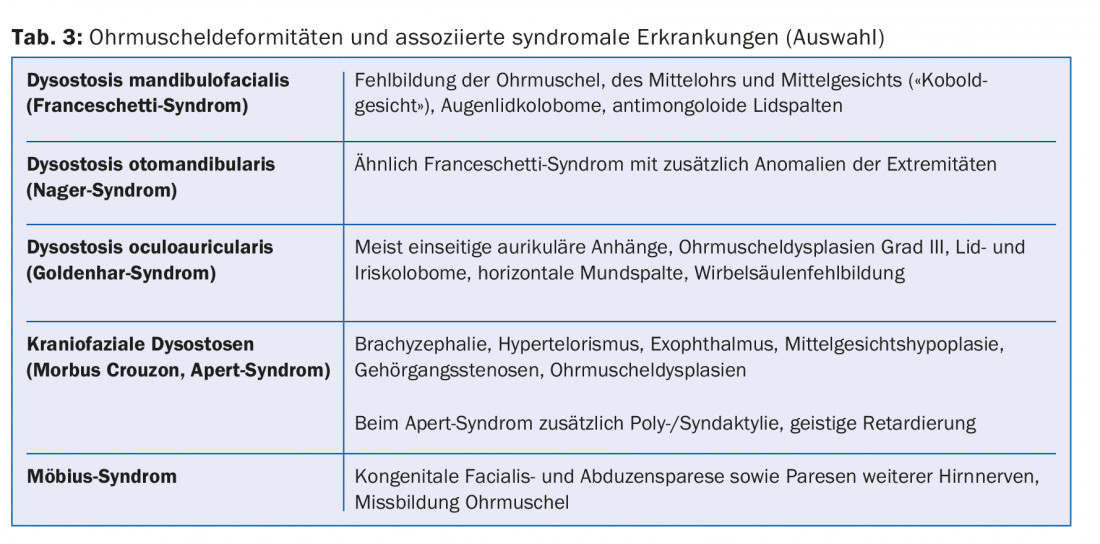

Not infrequently, moderate- and high-grade malformations of the auricle may also occur with dysplasias of the middle and/or inner ear, and in some cases these occur in the context of syndromal disorders (Table 3) [4]. In addition to genetic factors, exogenous factors (thalidomide, rubella embryopathy, other viral infections, alcoholism, etc.) [1] and unknown factors also play a role. The complexity of auricular malformations is explained by incomplete formation or fusion of the six mesenchymal auricular cusps around the sixth embryonic week [3,5].

Indication for therapy

Mild auricular malformations usually do not lead to hearing loss, but have a clinical relevance, because from the aesthetic point of view there may be an individual suffering, from which also the indication for treatment arises. In order to avoid psychological stress caused by teasing from classmates in kindergarten, children are usually operated on from the age of five. In principle, however, surgery is also possible at an older age.

A protruding auricle exists when the helix protrudes more than 1.5 cm from the lateral plane of the head when viewed from the front. The angle between the concha auriculae and the scapha should be about 90°, and the angle between the auricle and the mastoid plane should be about 30°. Causes for exceeding this mass are usually an insufficient or non-existent anthelical fold and an excessively large cavum conchae (Fig. 1) [6].

The costs of treatment are not covered by health insurance, but often a partial amount is covered by health insurance.

Therapy and surgical techniques

Conservative therapeutic approaches with splinting of the auricle have been described mainly in neonates and infants. In this procedure, the auricle is reshaped by splinting over a period of two weeks to six months, depending on the age of the child. The success rate is described as 70-100% [7,8]. However, this method has not yet become widely established, not even at our clinic, so that our own experience reports are lacking.

In principle, otoplasty can be performed under local anesthesia, but general anesthesia is preferred for young children. The correction of the protruding auricle is based on three basic principles; pure incision-scoring technique according to Senström, pure suture technique according to Mustardé or combined incision-suture technique according to Converse.

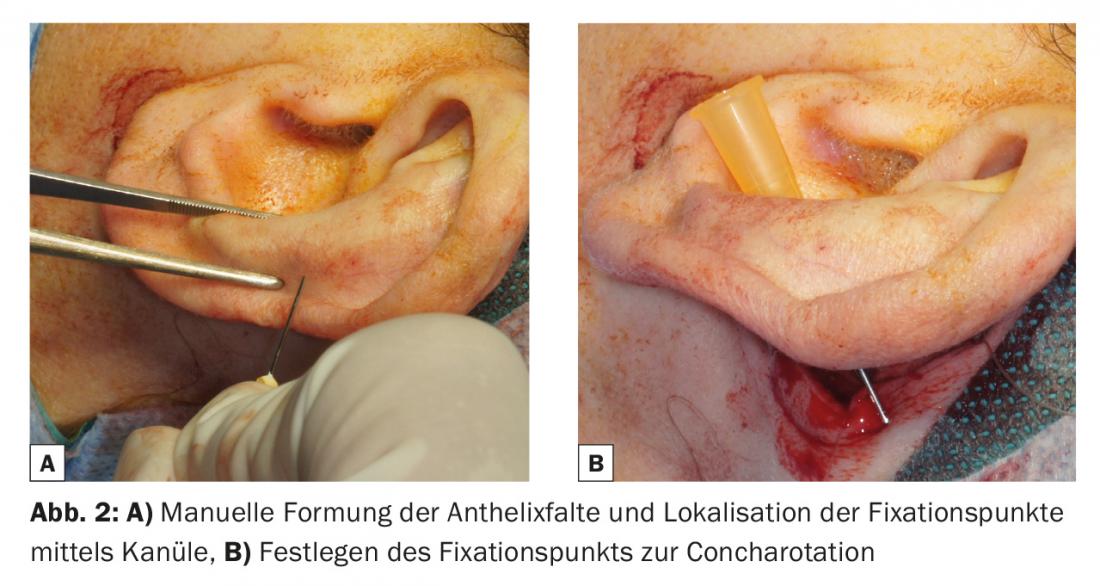

The scar can be easily concealed via a retroauricular incision approximately 1 cm lateral and parallel to the inframammary fold. Then the skin of the cartilage posterior surface is undermined while sparing the perichondrium. The skin over the mastoid is also dissected off, and the posterior auricular muscle can be resected, facilitating subsequent concharotation. An oversized concha can be reduced by crescentic cartilage resection. Folding of the skin on the anterior side of the concha can be reduced by generous undermining up to the entrance of the auditory canal. Cartilage sutures are used to close the gap created by the resection. When reshaping the anthelix, the helix is first manually moved back until the newly formed anthelix is still just surpassed by the edge of the helix (Fig. 2). The formed anthelix fold is now fixed with non-absorbable suture over several cartilage sutures. The cartilage is first punctured in the area of the scapha, then correspondingly in the area of the concha, so that the anthelix is formed to a greater or lesser extent by stronger or weaker thread traction. After that, other analogous sutures are placed cranially and caudally of it. If the cartilage is strong and difficult to shape, the sutures may tear if too much tension is applied. Then the cartilage can be appropriately weakened by scoring the cartilage anterior surface parallel to the anthelix axis or by thinning the cartilage posterior surface with the diamond bur. A protruding lobule can often be corrected with a VY suture.

Finally, the auricle is repositioned by rotation so that a concha-mastoid angle of 30° is achieved. Here, too, after prior testing with forceps to determine the most suitable point for rotation, fixation is achieved with a non-absorbable suture starting from the concha cartilage to the periosteum of the mastoid. (Fig. 2). In children, skin closure is performed retroauricularly with an absorbable suture (e.g. Monocryl 4-0) to avoid the need for suture removal.

During follow-up, a circular ear dressing is removed on the second day postoperatively. After that, a headband should be worn for four to six weeks to further protect the auricle.

Risks and complications

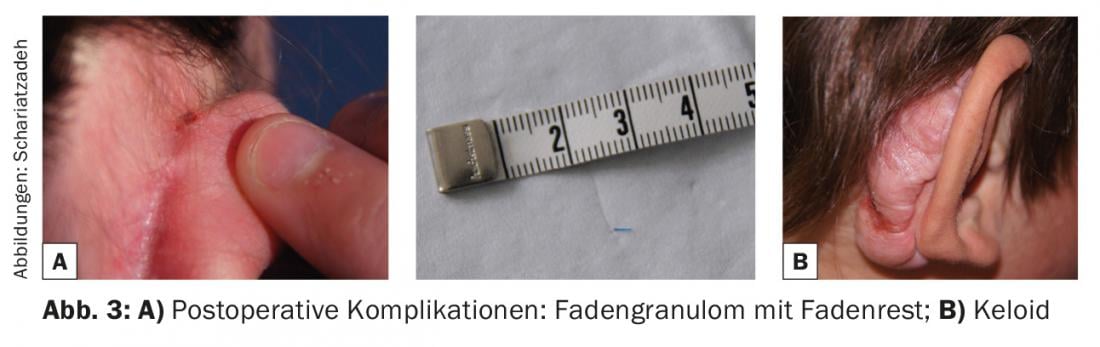

Complications are divided into early and late complications, where the former can occur up to two weeks postoperatively, while late complications can occur up to one year after surgery has been performed.

Early complications include postoperative pain and hypersensitivity in the area of the auricle, bleeding, in particular also subperichondral hematomas with the threat of cartilage necrosis, infections, and pressure ulcers, for example caused by the ear bandage. Rotation of the concha may cause narrowing of the ear canal. This can usually be prevented by pulling the auricle cranial-dorsally; otherwise, a cartilage excision in the area of the auditory canal may be necessary. Late complications include keloid formation or suture fistulas (Fig. 3), which manifest as nonhealing, punctate granulations; often a suture end is also visible. In these cases, the thread must be removed. If the otoplasty was performed more than six weeks ago, the removal of the sutures does not cause a recurrence of the deformity [5]. Residual deformities, asymmetries, and shape abnormalities may also occur, such as the auricle being too tight, the upper and lower portions of the auricle protruding (“telephone ear”), or the middle portion of the auricle protruding (“inverted telephone ear”) [1].

Literature:

- Weerda H: Surgery of the auricle. Injuries, defects and anomalies. Thieme 2004.

- Adamson P, et al: Otoplasty techniques. Facial Plast Surg 1995 Oct; 11(4): 284-300.

- Bartel-Friedrich S, Wulke C: Classification and diagnosis of ear malformations. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007; 6: Doc05.

- Strutz J, et al: Practice of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery. Thieme 2010.

- Braun T, et al: Developmental disorders of the ear in children and adolescents: conservative and surgical treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111(6): 92-97.

- Theissing J, et al: ENT surgical theory. Thieme 2006.

- van Wijk MP, et al: Non-surgical correction of congenital deformities of the auricle: A systematic review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009 Jun; 62(6): 727-736.

- Smith W, et al: Nonsurgical correction of congenital ear abnormalities in the newborn: case series. Paediatr Child Health 2005; 10(6): 327-331.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(8): 22-25