Pruritus is not only a sensory sensation, but is also intertwined with affective and cognitive aspects. Psychological processes such as stress can manifest cutaneously. Therefore, psychological clarification and therapy are worthwhile.

Chronic pruritus is a frequent accompanying symptom of skin diseases and can severely impair the quality of life due to its agonizing character. Conversely, it can be an expression or partial aspect of a mental disorder. In recent years, research into these psychosomatic relationships has been able to demonstrate clear correlations and identify psychotherapeutic treatment options. The following article provides an overview of psychological influencing factors, psychoneuroimmunological mechanisms and forms of therapy.

Psychosomatic aspects of skin diseases have been known for many years. In the sense of the biopsychosocial model, this is understood as the influence of psychosocial stress on dermatoses and, conversely, the effect of dermatosis on the psyche. More specifically, this includes effects of stress on inflammatory modulation, processing of negative affect and cognitions (e.g., anticipatory anxiety), and coping and integration of the disease state into the current life situation.

Suggestion, placebo and nocebo effects

Pruritus, like pain, is a complex sensory phenomenon that includes discriminative, cognitive-judgmental, motivational, and affective components. Accordingly, numerous studies have demonstrated that in addition to sensory areas, motor and affective areas (central anxiety centers, amygdala, hippocampus) are activated in the brain during the occurrence of pruritus. Even without the presence of dermatosis, pruritus can be subtly provoked. Thus, experimental studies in healthy subjects were able to induce reliable itching and scratching behavior by presenting pruritus-related visual stimuli (pictures of crawling insects, people scratching themselves) [1,2]. In addition to this mental induction, however, placebo and nocebo effects can also be demonstrated. In an experimental study, verbal suggestions to increase anticipatory anxiety significantly increased pruritus intensity after mechanical, electrical, and histamine stimuli in healthy subjects [3]. Conversely, in healthy subjects, subjective pruritus intensity after histamine application was significantly reduced by verbal downplaying [4]. Interestingly, these placebo effects can be exploited therapeutically in the long term through a combination of verbal suggestion and conditioning [5,6].

Stress and psychological comorbidities

The negative influence of stress on the course of chronic skin diseases such as neurodermatitis and psoriasis has been known for years. However, the incidence and severity of pruritus also correlate with psychosocial stress in the general population [7,8]. The forms of stress examined here included everyday adversities, stressful life experiences and traumas (“life events”), and certain personality traits (perfectionism, low tolerance).

In line with this, chronic pruritus is often associated with psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. Skin disease is generally associated with increased comorbidity for mental illness, with skin disease sufferers having nearly twice the prevalence (29%) of affective disorders such as anxiety or depression compared to the general population [9]. Patients with chronic pruritus also seem to suffer more frequently from mental illness. In a psychiatric evaluation of this subgroup (n=109), a psychiatric diagnosis could be made in over 70% and psychotherapeutic treatment was recommended in over 60% [10]. As mentioned at the outset, the neurofunctional mechanisms of these disorders overlap. Simplified, we can speak here of an increased anxious tension, which exerts a pruritus-promoting influence.

Scratching causes short-term relaxation, but long-term skin damage and conditioned behavior. Scratching is immediately experienced as relief and tension reduction, but usually worsens the skin condition. When there are no other forms of relaxation available during mental tension, the memory automatically activates the itch-scratch circuit. Breaking this vicious circle is difficult for many patients, because a self-imposed ban on scratching usually does not succeed. Structured behavioral programs such as Habit Reversal Training can better remedy this situation.

How stress gets into the skin

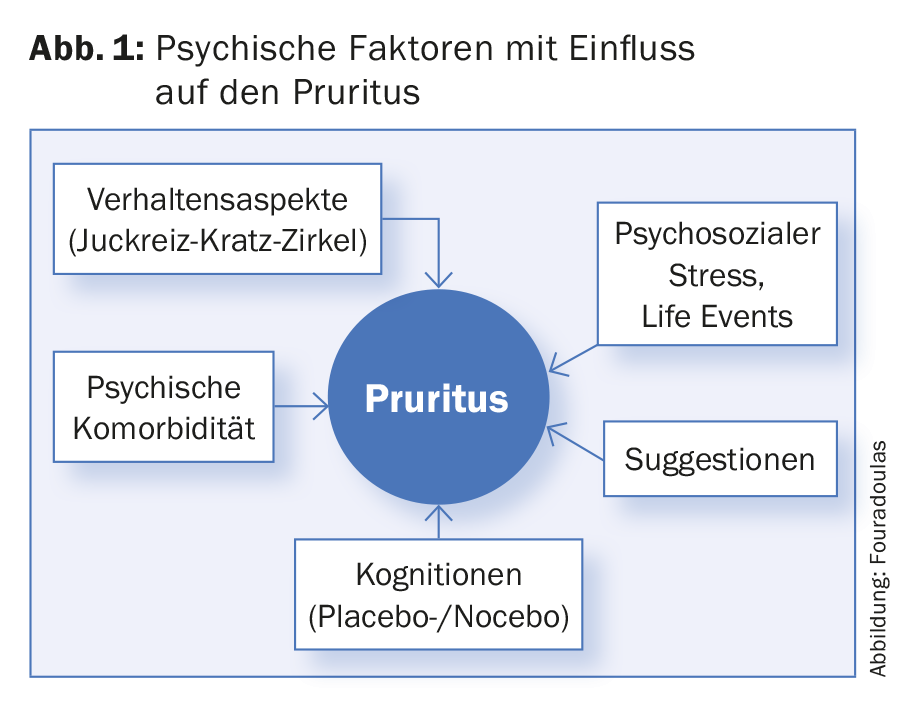

In addition to the aforementioned neurofunctional overlap, psychoneuroimmunological interactions also exist at the cellular level [11]. Basically, the immune system reacts with every stress response. Thus, receptors for stress mediators are found on every skin-derived or skin-infiltrating cell of the immune system. Cortisol, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and neuropeptides affect the humoral milieu of the skin via the three stress axes: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, sympathetic and cholinergic axis, and neuropeptide-neurothrophin axis. Chronic stress thus causes peripheral humoral inflammation and has pro-allergenic and pro-autoimmune effects. In this context, mast cells are in close contact with signal-mediating nerve fibers and can be activated by psychosocial stress. Those neurons are able to act efferently via the release of neuropeptides such as substance P (SP) and mediate neurogenic peripheral inflammation. SP systemically modifies the stress response by inhibiting the HPA axis and increasing sensitive perception and itch in the skin. In the animal model, stress thus leads to increased contacts between those neurons and mast cells with subsequent mast cell degranulation and thus histamine release. Thereby, the stress-induced SP release sensitizes the mast cells to other stimuli as well. According to these correlations between pruritus and psychological factors (Fig. 1) , it is obvious that, in addition to dermatological therapies, psychotropic drugs and psychological interventions should also be used and have proven to be effective.

Therapy

Psychosomatic treatment is based on the biopsychosocial profile of the affected person and should not only be symptom-based. At the beginning there is an extended psychosocial anamnesis. This should include the stress profile as well as evidence of mental illness and psychiatric history.

Psychoeducation: In a second step, the connections between psychological stress and pruritus or skin disease should be pointed out. This can build a broader understanding of the disease, which is what makes psychological treatment possible in the first place.

Pharmacotherapy: Based on the mentioned affective involvement in chronic pruritus, a psychopharmacological starting point can be derived. The best studied and most commonly used are antidepressants such as SSRIs (paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram) [12]. Further, tricyclics such as doxepin and amitriptyline are suitable for oral and even topical use, as they exert an antihistaminergic effect [13]. More recently, GABA analogues such as gabapentin and pregabalin have also been used because of their anxiolytic effect [14].

Relaxation procedures: If the pruritus is associated with an increased stress load, specific relaxation procedures are suitable, which should be practiced daily over a period of at least four weeks. Among the best-studied methods with similar efficacy for pruritus reduction are autogenic training (AT) and progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) [15]. In PMR, relaxation is achieved through consecutive tensing and relaxing of muscle groups. Thus, the user is active and maintains a physical sense of control. There are variants of different duration, but more important is daily practice, which allows training this relaxation response. In AT, the focus is on auto-suggestive influence on voluntary and smooth muscles. The user focuses on specific areas of the body and imagines perceptions such as heaviness, warmth, or depth of breath, resulting in relaxation over time. Regarding pruritus, skin-specific suggestions such as “the skin is relaxed and cool” can also be incorporated.

Itch control, habit reversal training (HRT): HRT is especially recommended when damaging scratching behavior exacerbates pruritus or is the main problem (itch-scratch circuit). This procedure was originally used for obsessive-compulsive disorders and aims to change the already conditioned itch-scratch behavior. HRT consists of the three steps of perception training, practicing a replacement action, and positive social feedback. The perception is deepened by a detailed description of the itch perception and scratch reaction. Subsequently, a substitute action such as fist closure or grasping an object is practiced. Finally, the social environment is included, which provides positive feedback on successful behavior.

Conclusion

The skin is functionally a versatile organ. In addition to its classic functions such as demarcation, perception and protection, it is also an organ of expression and encounter. In a broader sense, inner – and thus also psychological – processes come to the surface. Itching can thus signal increased internal tension and induce attention to this process. Ideally, this is followed by an exploration of the underlying processes. What does the body express that is not accessible to the person affected? What does he communicate through the skin that he can’t talk about? Scratching symbolizes a short-term relief action to relieve tension, which tends to do harm in the long run. Figuratively, it represents all of the short-term reaction patterns to undiscovered dysfunctional inner processes. The body thus demands attention and introspection from the conscious person with a willingness to change perspective, reflection and change.

Take-Home Messages

- Pruritus is a multidimensional experience that includes not only sensory but also affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects and can be triggered and modulated by placebo and nocebo effects.

- Chronic pruritus is often associated with psychosocial stress and affective disorders such as anxiety and depression and should be evaluated for these.

- Psychological treatment should be tailored to the underlying problem (stress levels, psychological comorbidity, pruritus control) after a thorough explanation of the psychosomatic context.

Literature:

- Lloyd DM, et al: Can itch-related visual stimuli alone provoke a scratch response in healthy individuals? British Journal of Dermatology 2013; 168(1): 106-111.

- Niemeier V, Gieler U: Observations during itch-inducing lecture. Dermatol Psychosom 2000; 1(Suppl 1): 15-18.

- van Laarhoven AI, et al: Induction of nocebo and placebo effects on itch and pain by verbal suggestion. Pain 2011; 152(7): 1486-1494.

- Darragh M, et al: The placebo effect in inflammatory skin reactions: the influence of verbal suggestion on itch and weal size. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2015; 78(5): 489-494.

- Bartels DJ, et al: Role of conditioning and verbal suggestion in placebo and nocebo effects on itch. PloS One 2014; 9(3): e91727.

- Sölle A, et al.: How to psychologically minimize scratching impulses: Benefits of placebo effects on itching using classical conditioning and expectancy. Journal of Psychology 2014; 222(3): 140-147.

- Dalgard F, et al: Itch in the community: associations with psychosocial factors among adults. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2007; 21(9): 1215-1219.

- Yamamoto Y, et al: Association between frequency of pruritic symptoms and perceived psychological stress: a Japanese population-based study. Archives of Dermatology 2009; 145(12): 1384-1388.

- Dalgard FJ, et al: The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2015; 135(4): 984-991.

- Schneider G, et al: Psychosomatic cofactors and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic itch. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology: Clinical dermatology 2006; 31(6): 762-767.

- Peters EMJ: Stressed skin? – Current status of molecular psychosomatic correlations and their contribution to causes and consequences of dermatological diseases. Journal of the German Dermatological Society 2016; 14(3): 233-254.

- Sanders KM, Akiyama T: The vicious cycle of itch and anxiety. Neuroscience Biobehavioral Reviews 2018; 87: 17-26.

- Lee HG, et al: Topical ketamine-amitriptyline-lidocaine for chronic pruritus: a retrospective study assessing efficacy and tolerability. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2017; 76(4): 760-761.

- Matsuda KM, et al: Gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of chronic pruritus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2016; 75(3): 619-625.

- Schut C, et al: Psychological interventions in the treatment of chronic itch. Acta Derm Venereol 2016; 96(2): 157-161.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(5): 6-8