Anxiety disorders can be treated well using cognitive behavioral therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy. In this context, confrontation with feared situations represents the core element of the various forms of therapy.

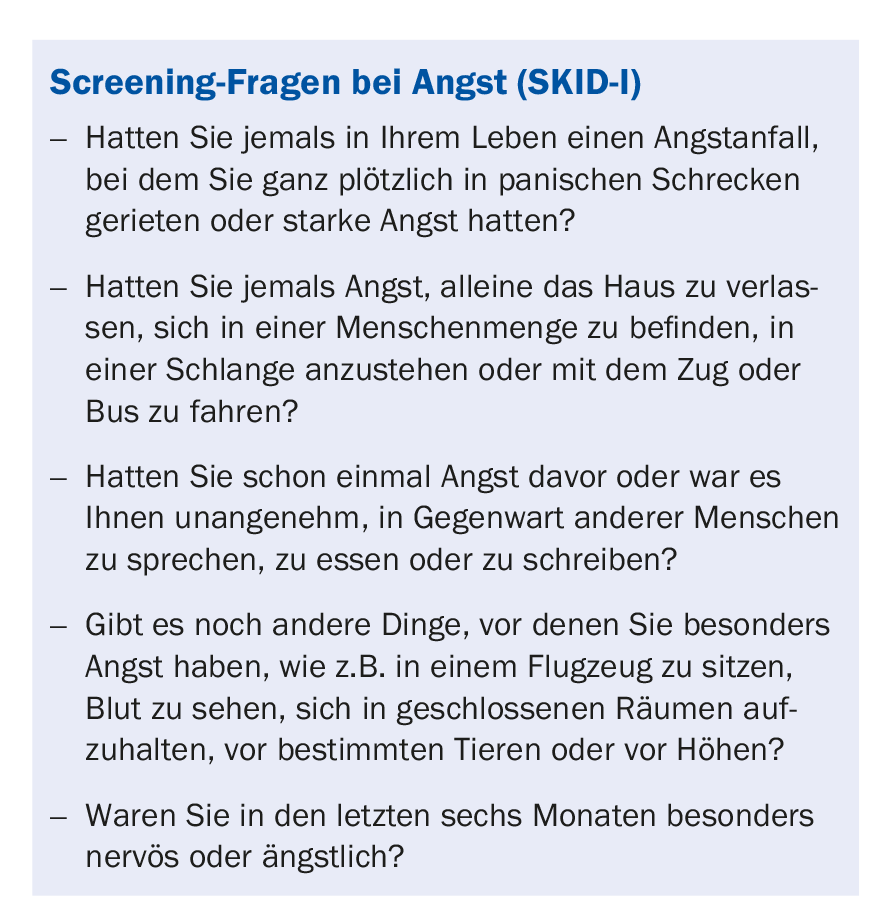

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental illnesses. About 15-20% of people suffer from an anxiety disorder at some point in their lives. In general practice, more than 10% of patients are affected. Less than 50% of cases are diagnosed (screening questions in box) and only a small proportion are treated. In contrast, anxiety disorders tend to be well and effectively treatable, especially when diagnosed early.

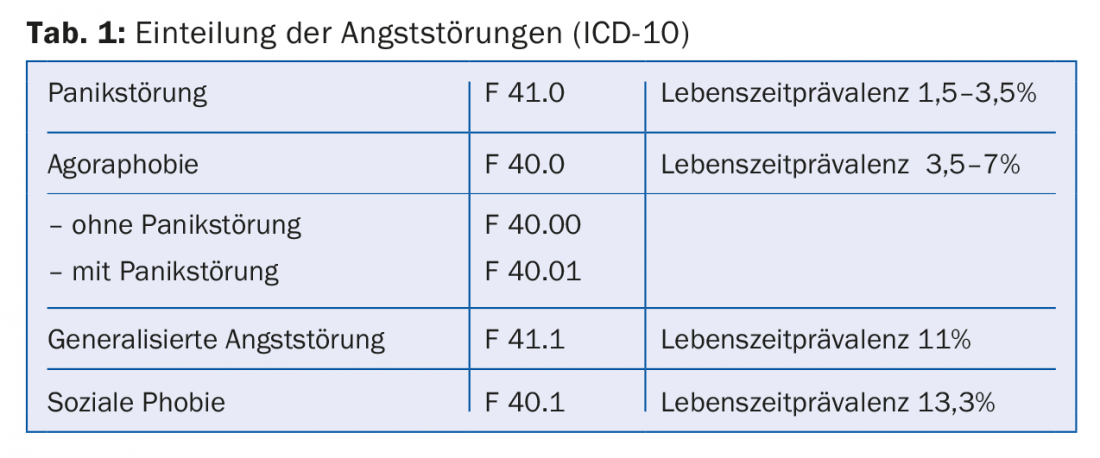

In the treatment of anxiety disorders, psychotherapy represents a central element. Results of psychotherapy research suggest that disorder-specific treatment leads to better outcomes than nonspecific therapy [1]. The combination with antidepressant pharmacotherapy, which has an anxiety-relieving effect, is likely to be useful in many cases. Meanwhile, a variety of disorder-specific psychotherapeutic approaches have been developed, manualized, and empirically tested. It is striking that the specific approaches of the different schools of therapy have similar procedures, highlighting confrontation with the anxiety-provoking situation as a common core element [2]. The effectiveness of this method was recognized not only by the behaviorists, but already in 1919 by Sigmund Freud [3]. In the present article, the main three anxiety disorders according to ICD-10 (Table 1) and their psychotherapeutic treatment options are presented.

Panic disorder and agoraphobia

In panic disorder (ICD-10: F 41.0), sufferers suffer from sudden, violent anxiety attacks with physical symptoms of fear (racing heart, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, etc.) combined with fear of losing control, going “insane” or fainting, or dying. In pure panic disorder without agoraphobia, the panic attacks occur suddenly and without cause. However, panic disorder is usually associated with agoraphobia (ICD-10: F 40.0). Agoraphobia, in turn, may occur with or without panic attacks. In agoraphobia with panic disorder, the described panic attacks are joined by fear of places where escape would be difficult or help would be difficult to access in the event of a panic attack. In the course, a vicious circle occurs, consisting of avoidance behavior and fear of fear.

Cognitive behavioral therapy: It is believed that panic attacks are caused by a misinterpretation of basically harmless physical symptoms. Therefore, patients should learn to interpret and classify physical signals appropriately and to react to them accordingly. In addition to providing information about the disorder (psychoeducation) based on psychophysiological models (e.g., “vicious circle model of anxiety” or “stress model” to explain the role of altered perception threshold of physical symptoms in constant anxiety), relaxation procedures, stress management training, and exposure are used. In addition, the restructuring of anxiety-provoking thoughts plays an important role.

Exposure is distinguished between interoceptive exposure and in vivo exposure. In interoceptive exposure, for example, physical activity increases the heart rate or hyperventilation produces dizziness. It is crucial that the patient experiences that the resulting body symptoms are harmless and can be influenced and down-regulated independently. This should lead to an extinction of the conditioned fear response. If agoraphobia is present, exposures are performed in vivo, where patients are directly confronted with the fear-inducing situation after cognitive preparation. This can take the form of flooding, in which the patient is confronted with highly anxious situations at the outset, or of staged exposure, starting with comparatively mild confrontations and gradually increasing the intensity [4].

Psychodynamic psychotherapy: In recent years, manualized treatment approaches have also been developed in psychodynamic therapy, such as panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy (PFPP) for the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia [5]. The associated psychodynamic theory postulates that panic symptoms have a specific emotional meaning related to intrapsychic and interpersonal conflicts. According to the theory, anxiety symptoms continue until the patient can tolerate the meaning of panic and the associated conflicts.

PFPP is divided into three phases: The first phase is devoted to active exploration of the circumstances that preceded the onset of the panic disorder, the patient’s thoughts and feelings during the panic attacks, and the (unconscious) meaning of the symptoms. The second phase attempts to address the emotionally significant issues that play a role in the genesis of the panic episodes and to analyze their psychodynamic connections, such as conflicts of the patient related to separation or expression of anger. Since conflictual expectations of the patient also manifest themselves in the relationship with the therapist, working on dysfunctional patterns in the transference is of particular importance. This helps the patient to realize that the fear of an emerging catastrophe is an expression of an inner conflict which has its roots in earlier, formative relationships and does not reflect the current reality. The goal of this phase of treatment is to reduce vulnerability to panic attacks by making the patient aware of the unconscious emotional and interactional style that characterizes them. In the third phase of treatment, it is important to focus on the end of treatment in a timely manner, as patients with panic disorder often have significant difficulty with separation and independence. Revisiting and working through these conflicts in the therapeutic relationship allows the patient to put into words and understand the fantasies involved, making separations less anxiety-provoking.

Generalized anxiety disorder

Patients with generalized anxiety disorder (ICD-10: F 41.1) suffer from excessive anxiety and worry related to general or specific life circumstances. The occurrence of this anxiety, unlike panic disorder, is not situationally circumscribed or seizure-like, but it is present in varying intensity almost constantly. Patients are tormented, for example, by constant worries that something bad might happen to them, such as accidents happening to them or falling ill. Patients often also worry about their constant worrying, and these “meta-worries” can be very distressing. The permanent tension leads to nervousness, concentration and sleep disorders as well as physical symptoms such as trembling, muscle tension, sweating, drowsiness, palpitations, dizziness, digestive problems or diarrhea.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy: as with the other anxiety disorders, several elements are used in the cognitive-behavioral therapy treatment of generalized anxiety disorder [6]: In addition to general information transfer, in-sensu-exposures to feared personal disasters and related worries are conducted (“worry confrontations”). In confrontations in vivo, it comes down to eliminating inappropriate safety behaviors. This may consist, for example, of not calling one’s children excessively often when staying out in the evening. For patients, it’s about learning to tolerate rather than avoid fearful experiences. The cognitive therapy component involves reassessing unrealistic assumptions about the benefits and harms of worry, as well as developing a realistic assessment of the likelihood that problems could result in negative consequences. To this end, behavioral experiments are also conducted in order to systematically test fears that are met with safety behavior with regard to their reality content. Emotion regulation techniques such as relaxation techniques and mindfulness are also used.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy: psychodynamic treatment manuals for patients with generalized anxiety disorder build on the supportive-expressive therapy (SET) developed by Luborsky [7], which includes both supportive (supportive) and interpretive (expressive) interventions. The focus is on the patient’s central relationship conflict issues (ZBKT). This refers to conflictual patterns of experience and behavior that are repeated in different relationships of the patient. The assumption is that psychological symptoms are based on a conflict that is repeated in various relationships. In treatment, again, special emphasis is placed on the development of the therapeutic relationship. It is assumed that the central relationship pattern is also manifested in this relationship, which facilitates a common recognition of the pattern [8]. Thus, in terms of content, the treatment focuses on the repetitive interpersonal conflicts: in the current relationships, in the transference to the therapist, and in the earlier relationships during childhood and adolescence.

Social phobia

Social phobia (ICD-10: F 40.1) or social anxiety disorder according to DSM-5 is one of the most common anxiety disorders. Affected individuals are afraid of situations in which they are the center of attention (e.g., public speaking). They fear acting embarrassingly or awkwardly and being judged negatively by others. Avoidance behavior usually ensues, which can perpetuate the disorder.

Cognitive behavioral therapy: psychoeducation in the context of cognitive behavioral therapy provides insight into the relationship between unrealistic beliefs about social standards, increased tension, dysfunctional thoughts, inward focus of attention, and avoidance behaviors. In the context of cognitive restructuring, exaggerated negative self-evaluations are compared with reality. Based on the assumption that social phobia is caused by deficits in the ability to communicate and interact, social skills training is used. In the process, the patient should e.g. give a speech in a role play in front of other group participants, with video feedback if necessary. Additionally, exposure exercises or behavioral experiments are used. For example, the patient should deliberately expose himself to a subjectively particularly embarrassing situation in public, observing the reaction of his surroundings [9]. In this way, feared consequences are examined with regard to their real threat and dysfunctional safety behavior is reduced.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy: The establishment of an accepting, supportive relationship with the therapist is central, as it provides a secure basis for enabling the patient to engage in exploratory behavior and self-exposure. Again, the patient is encouraged to actively confront anxiety-provoking social situations and discuss his or her experiences with the therapist. This takes into account the patient’s social limitations due to lack of experience in social interactions. The therapist’s supportive stance can correct the patient’s past experiences of being shamed in relationships with significant others. Thus, the relationship with the therapist contributes to the improvement of self-esteem regulation and impulse control. Treatment focuses on shame as a guiding affect, confronts the patient with his inflated self-demands, and explores the implicit expectations placed on the patient by previous caregivers [10].

Summary

In the psychotherapy of anxiety disorders, confrontation with the anxiety-provoking situation represents the common core element of treatment across all schools. Cognitive behavioral therapy has the best empirical evidence for its effectiveness. Psychodynamic psychotherapies are particularly important when behavioral therapy is ineffective (or when the patient has a preference) or when there are comorbid personality disorders.

Take-Home Messages

- Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental disorders.

- Psychotherapeutically, there are several empirically well-proven specific treatment options, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy.

- Confrontation with feared and avoided situations represents the common core element of the various forms of therapy.

- Avoidance behavior leads to significant impairment of the sufferer as well as maintenance of the anxiety disorder.

- If there is an insufficient response to psychotherapy, additional pharmacotherapeutic options may be considered.

Literature:

- Bandelow B, et al: German S3 guideline treatment of anxiety disorders. Status 2014.

- Benecke C, Staats H: Psychoanalysis of anxiety disorders. Models and therapies. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer 2017.

- Freud S: Paths of psychoanalytic therapy. In ibid: Works from the years 1917-1920 (Series: Collected Works, Vol. XII). Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer 1999: 181-194.

- Schneider S, Margraf J: Agoraphobia and panic disorder. Göttingen: Hogrefe 1989.

- Milrod BL, et al: Manual of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press 1997.

- Becker E, Margraf J: Generalized anxiety disorder. Weinheim: Beltz 2002.

- Luborsky L: Introduction to analytic psychotherapy. A textbook. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Rupprecht 1995.

- Crits-Christoph P, et al: Brief supportive-expressive psychodynamic therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. In Barber JP, Crits-Christoph P, ed: Dynamic Therapies for Psychiatric Disorders (Axis I). New York: BasicBooks 1995.

- Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M: Social phobias. A congitive behavioral therapy treatment manual. Weinheim: Beltz 2003.

- Leichsenring F, Beutel M, Leibing E: Psychoanalytic-oriented focal therapy of social phobia. Psychotherapist 2008; 53(3): 185-197.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(9): 19-22