Burnout has been conceptualized by occupational psychologists and, in terms of a syndromal approach, comprises the three dimensions of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization/cynicism, and reduced subjective performance evaluation, which is associated with a loss of confidence in one’s own professional abilities. The cause is thought to be a chronic imbalance between the demands of work and personal resources, which can lead to physical and mental exhaustion. Due to similar and/or overlapping symptoms between burnout and depression, but also sleep and anxiety disorders, the differential diagnostic differentiation can be difficult at first. Burnout therapy should be individually oriented to the usually multifactorial causes and take into account the severity of the symptoms.

The term “burnout” was first coined by New York psychoanalyst H.J. Freudenberg in 1974 [1]. In doing so, he described a process he had observed among volunteers at crisis intervention organizations. In these cases, mental and physical exhaustion occurred after longer phases of increased professional stress, accompanied by irritability and cynicism towards their clients and the feeling of being “burnt out”.

Conceptualization of burnout

The conceptualization of burnout goes back to the industrial psychologists Christina Maslach and Susan Jackson [2] and includes the following three dimensions in terms of a syndromal approach:

- Emotional exhaustion associated with the experience of emotional and physical powerlessness.

- Depersonalization/cynicism in the sense of a jaded, sometimes callous response to clients.

- Decreased subjective performance appraisal, which is accompanied by a nagging sense of professional failure and loss of confidence in one’s abilities.

Maslach and coworkers developed what is now a widely used instrument for assessing burnout, the “Maslach Burnout Inventory” (MBI).

Phases of burnout

Burnout is understood and described as a process [3] that develops under chronic stress in the workplace and over characteristic phases.

Phase 1: Increased commitment to work goals, overtime while foregoing recreation and overvaluing the job within the concept of life.

Phase 2: The initial increase in motivation is followed by a phase of exhaustion, negative attitudes toward work (feeling exploited; lack of recognition and reluctance to work), and withdrawal, which can extend into social life.

Phase 3: In addition, emotional reactions with irritability, impatience, bitterness, blaming, and giving up previously important life goals.

Stage 4: Work organization, thinking skills as well as motivation and flexibility are limited and actually reduce performance at work.

Phase 5: If stress continues without countermeasures, psychosomatic complaints (tension, pain, sleep disorders, cardiovascular problems, etc.) occur. The ability to relax and demand rest during leisure time is diminishing. Substance abuse for relief and attempted performance enhancement may occur.

Stage 6: onset of clinical depression to suicidality.

In this context, the syndromal work psychological concept of burnout does not represent a medical diagnosis and is therefore not included in the nosological systems in ICD-10 or DSM-IV.

Burnout etiology

A chronic imbalance between the demands of work and personal resources is assumed to be the cause of the development and maintenance of burnout. Social and organizational psychological factors as well as stress levels at work play an important role.

On the part of the affected individual, personality traits such as excessive demands, perfectionism, an exaggerated need for help, or excessive career expectations, as well as possibly also high neuroticism scores, a tendency to feelings of guilt, and low self-esteem play a role [4]. In addition, employees without sustainable social ties have an increased risk of suffering from burnout. Risk factors at the workplace are low support from work colleagues and few opportunities to shape one’s own work (“low job control”) combined with high demands [4].

In addition, favorable as well as unfavorable coping strategies were identified. Unfavorable coping strategies tend to aim at short-term relief, but in the long run they maintain or even intensify the stress situation (substance abuse, social withdrawal, avoidance behavior, escape, self-pity, resignation). Protective coping strategies include proactive elimination of sources of stress, positive self-instruction, the ability to trivialize at times, and self-regulation and humor.

Physical effects of burnout

Chronic stress exposure can have an impact on the physical condition of individuals. Since stress has an important role in the pathophysiology of burnout, some studies have been conducted on the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and the results are still inconsistent so far [5]. Thus, it has been shown that even the anticipation of stress before a workday alters the early morning cortisol response. It is assumed [5] that chronic stress initially causes hyperactivity of the HPA axis, which, however, turns into hypofunction after exhaustion of the adaptive reserve capacity and thus correlates with burnout.

Sleep for burnout

Sleep complaints are a common symptom of burnout. They also occur independently of comorbid depression and further maintain the vicious cycle of exhaustion and insufficient recovery. In this context, sleep disturbances represent another risk factor for the development of depression and also lead to a change in HPA axis regulation.

Burnout and depression

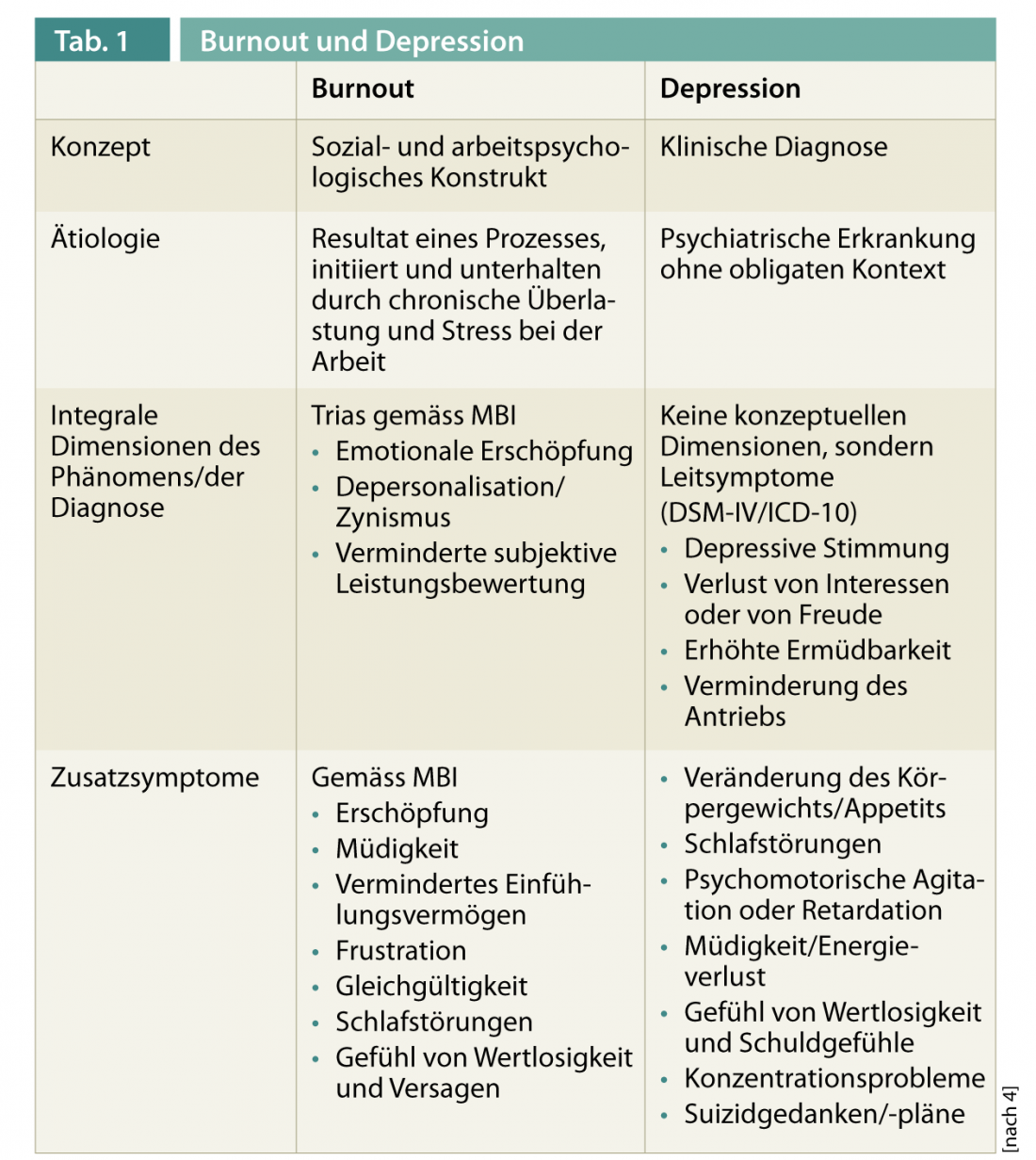

The differential diagnostic differentiation between burnout and depression but also sleep and anxiety disorders can be difficult at first due to similar and/or overlapping symptoms. Moreover, according to a Finnish cross-sectional study, as the severity of burnout increases, the likelihood of depression increases up to 50% [6]. A meta-analysis across 12 studies showed that depression and emotional exhaustion overlap. Ultimately, however, depression and burnout are considered two separate phenomena with common characteristics [7] based on different concepts (Table 1). Burnout is seen in a causal relationship with chronic (occupational) stress and does not meet any existing medical diagnostic criteria. Depressive disorders are medically defined mental illnesses that cannot be reduced to occupation [4]. The likelihood of depressive symptoms increases with the severity of the burnout and can lead to full-blown depression.

Therapy

Treatment of burnout is indicated when there is relevant subjective suffering and/or relevant impairment of important areas of life. Burnout therapy should be individually oriented to the usually multifactorial causes and take into account the specific needs of the patient as well as the severity of the symptomatology [7]. Talk therapy should always be offered and recreational spaces should be created through relaxation exercises, creative therapies or sports therapies [8]. Striking a balance between commitment and reward is the primary goal of psychotherapeutic procedures. In case of severe symptoms, additional psychopharmacotherapy is indicated.

Furthermore, organization-related interventions are important, even if they are difficult in some cases: Optimization of work processes, coaching, positive feedback from supervisors and employees, and adjustment of work schedules, e.g., in the case of shift work. Cognitive behavioral training and job-oriented training with qualified professionals are useful [9].

In moderate to severe forms of burnout with suicidality, the patient should be referred to a psychiatrist. If the course of therapy is difficult, a consultation with a specialist may also be advisable.

Treatment taking into account the degree of severity

Sleep disturbances already occur in burnout of milder intensity – even before a significant depression or anxiety component. Their elimination is often the first step in treatment. In addition to optimizing sleep hygiene, this includes adjusting lifestyle with moderate physical activity (walking, swimming, cycling, progressive muscle relaxation) and a healthy diet. If necessary, phytotherapeutics (e.g., valerian and hop preparations) or, in the case of pronounced sleep disorders, hypnotics of the benzodiazepine receptor agonist type can be used for a short time. If the symptoms require prolonged drug treatment, sleep-promoting and sleep-normalizing antidepressants should be used.

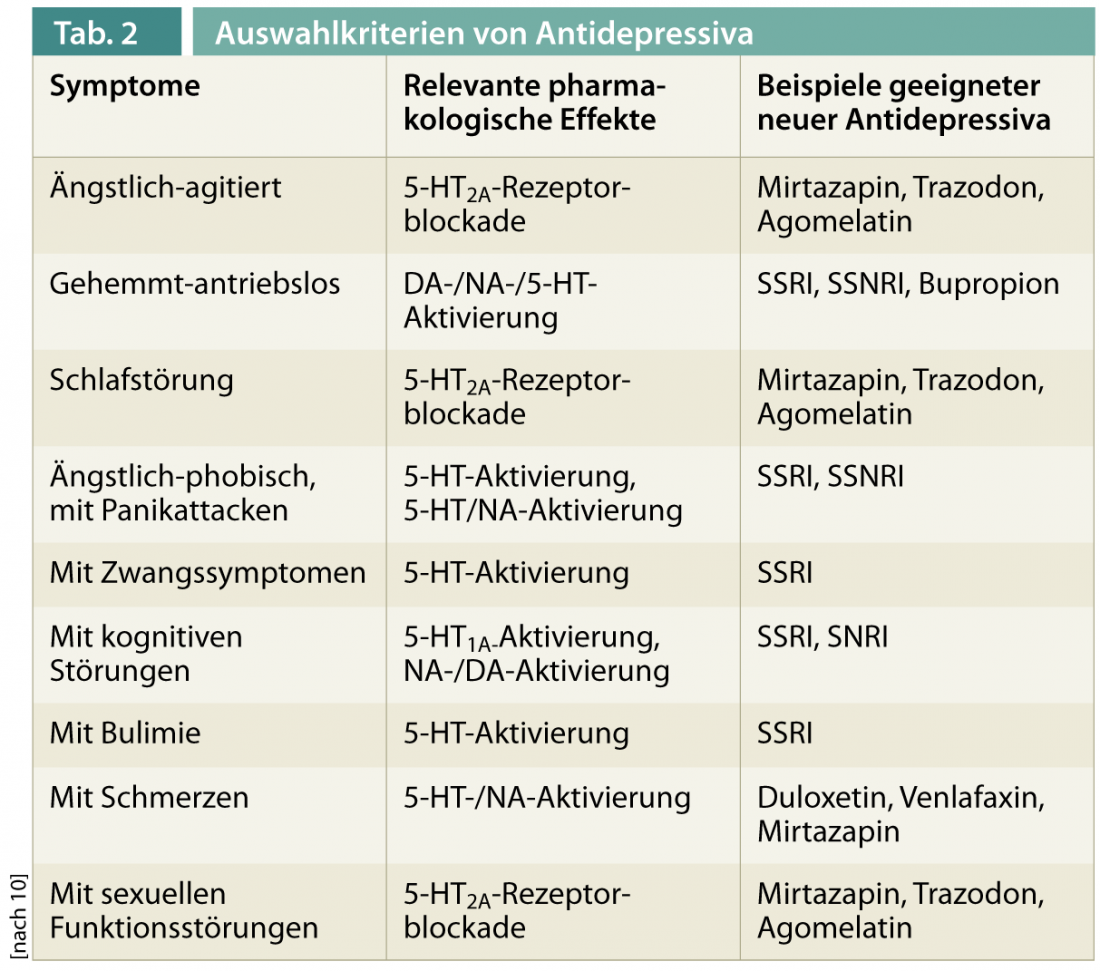

If burnout is present with significant depressive or anxiety symptoms, the use of antidepressants should be used in addition to psychotherapeutic intervention [4]. The therapy can be based on the treatment recommendations for depression or anxiety disorders (Tab. 2: Antidepressants) [10, 11]. A favorable social network of friends and family members was found to have a positive effect on health, but its extent was limited. The most effective measures for prevention and relapse prophylaxis in the case of burnout are social support at the workplace itself, support from work colleagues and understanding from superiors [12], which is why targeted interventions, possibly with employer discussions, and coaching can be helpful here.

Johannes Beck, MD

Prof. Dr. med. Edith Holsboer-Trachsler