In the worst case, peripheral arterial disease (pAVD) can lead to vascular occlusion and necessitate amputations; the risk of heart attack or stroke is also significantly increased in those affected. Nevertheless, this serious circulatory disorder of the blood vessels supplying the extremities often remains undetected and is not adequately treated. In this context, the therapeutic options are manifold.

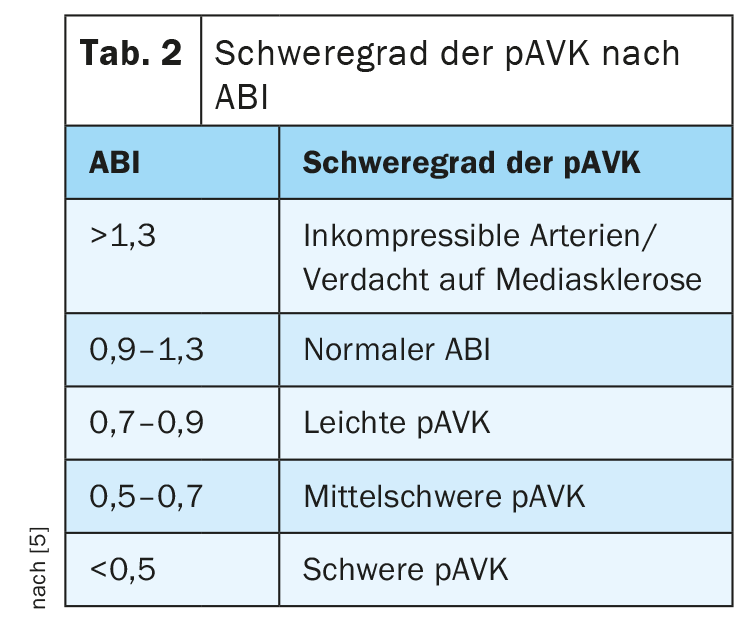

Studies show that patients with simple PAOD are undertreated with regard to their risk factors and concomitant diseases, according to Jan-Tobias Hensel, MD, Senior Physician, University Medical Center, Baselland Cantonal Hospital [1,2]. This is despite the fact that the prevalence of symptomatic or manifest pAVD in patients aged 45-75 years in the general population is 8.2% (men) and 5.5% (women), respectively [3]. Risk groups include those over 65 years of age and patients over 50 years of age with risk factors for atherosclerosis, i.e. diabetes mellitus, nicotine consumption, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, or positive family history. In addition, patients of any age with diabetes mellitus and another risk factor for atherosclerosis are included, as well as patients with known atherosclerosis in another organ, such as coronary artery disease, carotid stenosis, subclavian stenosis, renal artery stenosis, or mesenteric artery stenosis. In patients older than 65 years, 21% have an ankle-brachial index (ABI) <0.9 or manifest pAVD. In addition, pAVD is associated with significantly increased mortality, both in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients [4].

Medical history and clinical examination

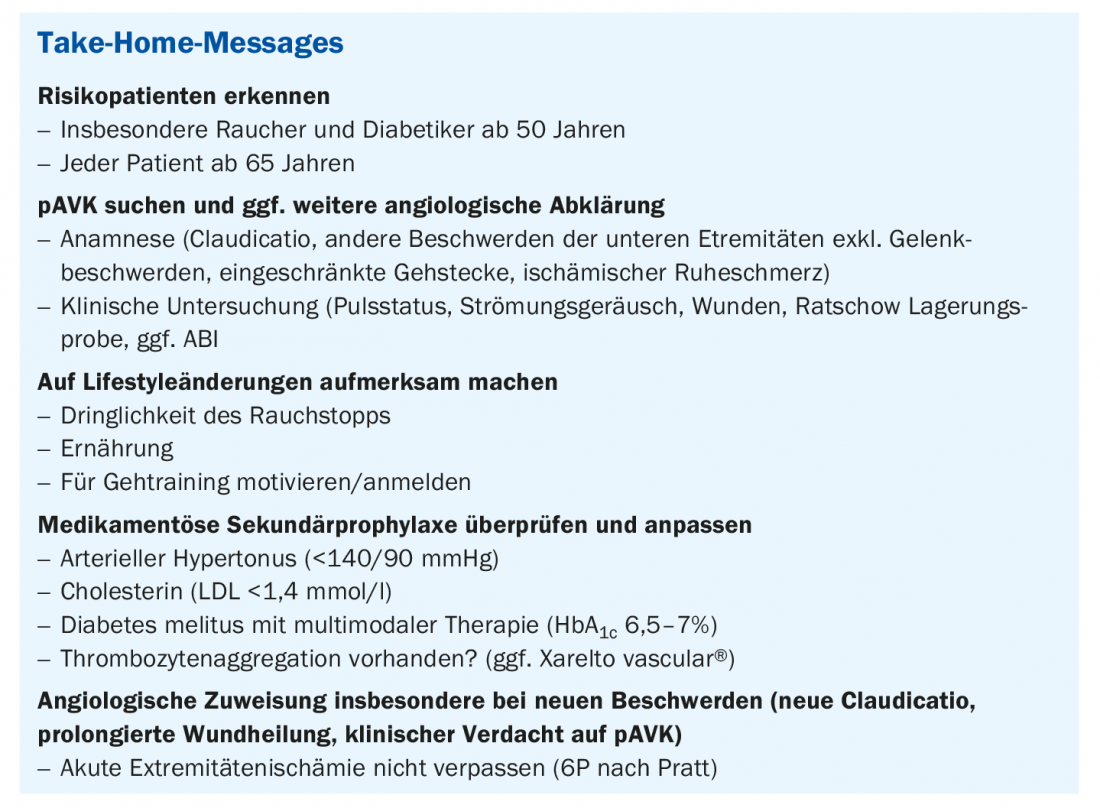

PAD results from narrowing of the extremity arteries or the aorta, usually due to arteriosclerotic plaque. A number of influences can promote these processes, such as smoking, obesity and lack of exercise. Classically, pAVD is characterized by intermittent claudication, the so-called shop window disease as a sign of restricted peripheral circulation. This results in a feeling of fatigue as well as tension, muscle cramps, or pain in the lower extremities, which are reproducible with physical exertion and improve with consistent rest [5]. Although pAVD is also colloquially referred to as “shop window disease,” it should be noted that approximately two-thirds of patients with confirmed pAVD do not have the classic claudication symptoms, but have “atypical” symptoms or are asymptomatic [6]. The classification of pAVD according to Fontaine or Rutherford ranges from asymptomatic pAVD to limited walking distance to ischemic rest pain and necrotic manifestations (Tab. 1) [7] Ischemic rest pain occurs by definition over >2 weeks duration, especially at night, which can be explained by a decrease in cardiac output and the resulting reduced perfusion of the limb.

Pulse status and flow murmur should not be disregarded during the clinical examination. Although pulse palpation alone with a sensitivity of 20% is not sufficient for the detection of pAVD, pulse status should be checked at the inguinal, popliteal fossa, tibial, and pedal vascular territories. The sensitivity of flow sounds is 75%, and the specificity is 40% in combination with pulse palpation.

A further clinical examination for the diagnostic clarification of pAVD is the positioning test according to Ratschow, which provides initial information about the functional extent of the occlusive disease. The Ratschow test can be very informative in terms of differential diagnosis, explains Dr. Hensel. During this procedure, the patient is placed on his back and asked to raise his legs to a vertical position and perform circular movements in the ankle joint for two minutes. The patient is then asked to sit up, with the legs hanging freely from the couch. In healthy patients there is no pain during movements, after sitting up the foot reddens within five seconds and the veins fill within the next five seconds. If pAVK is present, the affected leg already blows off during the movement phase. After sitting up, there is a delay in the reddening of the affected leg; accordingly, the veins fill up with a delay.

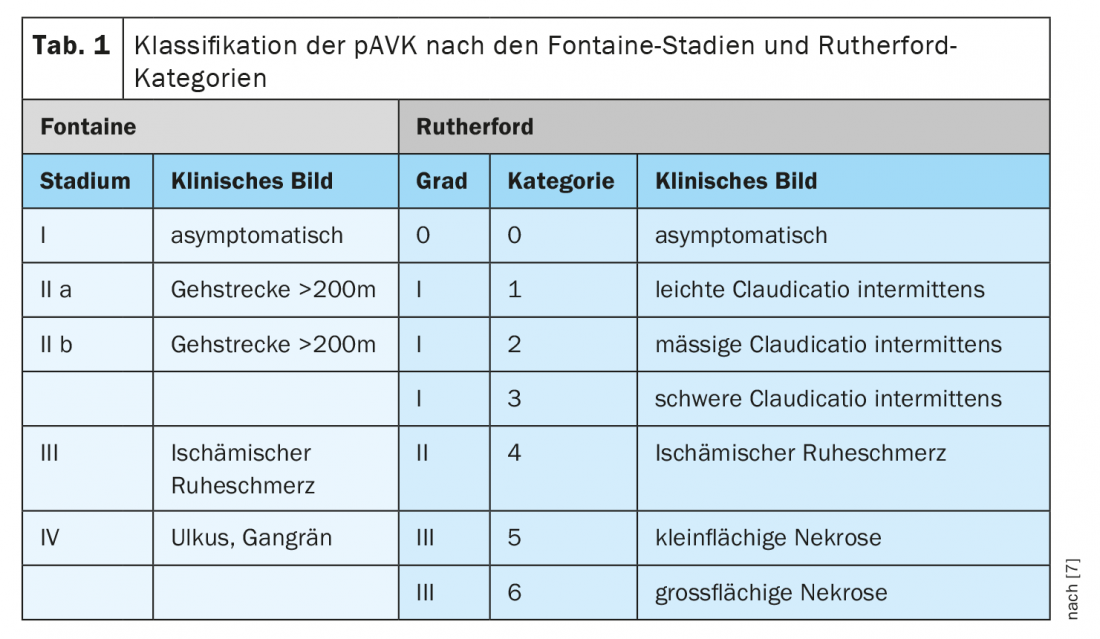

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) can also be used to estimate cardiovascular risk and assess the progression of pAVD, with pathologic values having high specificity but low sensitivity. In vascularly healthy patients, the ABI ranges from 0.9 to 1.3; an ABI value below 0.9 is pathognomonic for pAVD (Table 2) [8].

In case of clinical suspicion, an emergency clarification should be performed

Clinical signs of acute extermities ischemia include Pratt’s 6Ps: pain, paleness or pallor, pulelessness, paralysis, paresthesia, and prostration; and cardiac or arterial etiology or occlusion of arterial reconstructions. In these cases, interventional or surgical revascularization should be performed as soon as possible. Ideally, an inhibition of the progression of atherosclerosis is achieved; further therapeutic goals include risk reduction of peripheral vascular events, as well as reduction of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, pain reduction, and improvement of exercise tolerance, walking performance, and quality of life. Whereby both vascular surgery and endovascular arterial reconstruction, according to the S3 guideline, should be the result of a reasonable interdisciplinary, stage-appropriate balancing of effort, risk, and event [7].

Regular walking training brings benefits

Structured walking training is the most important non-drug therapy for the consistent treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, this has been demonstrated in various Cochrane reviews [7]. Furthermore, the long-term functional outcome of gait training alone is not inferior to vascular interventions in patients with claudication [9]. There is a significant increase in walking performance on the treadmill and a decrease in claudication after gait training [10]. It should be noted, however, that the effectiveness of daily unsupervised gait training is significantly worse than the effectiveness of a structured supervised training program.

Basic measures at a glance

Lifestyle changes: The basics of basic treatment primarily include exercise, weight loss, diet optimization, and independent or structured gait training. Furthermore, a recommendation to prompt nicotine cessation should be made at each doctor’s visit, with medication support if necessary.

Arterial hypertension: In hypertension, the target blood pressure should be <140/90 mmHg; if tolerated, intensified therapy also shows benefits, as demonstrated, for example, in the SPRINT (“Systolic Pressure Intervention Trial”) study [13]. Otherwise, ACE inhibitors and ATII antagonists [7] should be preferred.

Dyslipidemia: In dyslipidemia , the target LDL should be <1.4 mmol/l². For patients who do not achieve target LDL levels despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, PCSK9 inhibitors can be considered as another therapeutic option. [12]. However, this requires a request to the medical officer (angiology, cardiology, endocrinology, nephrology, neurology). In addition, special patient instructions for application are necessary.

Diabetes mellitus: diabetes mellitus should also have a HbA1c target range depending on age/comorbidities (6.5-7%/<7.5%). And it should be paid attention to a meticulous foot care, if necessary, pressure-relieving insoles should be resorted to especially in polyneuropathy.

Atherosclerosis: In atherosclerosis, monotherapy with aspirin or clopidogrel should be given because of platelet aggregation. In addition, Xarelto vascular® is also available (2.5 mg 1-0-1 in addition to asperine). Xarelto vascular® is a valid option when dual platelet inhibition is no longer required. In particular, younger high-risk patients <65 years benefit from this drug administration. Older patients >75 years are at increased risk of bleeding [11].

Literature:

- Hensel JT: Peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Family Physician Continuing Education Days, Sept. 08, 2021.

- Hirsch AT, et al: Gaps in public knowledge of peripheral arterial disease: the first national PAD public awareness survey. Circulation 2007, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.725101.

- Kröger K, et al: Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease – results of the Heinz Nixdorf recall study. Eur J Epidemiol 2006, doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-0015-9.

- Diehm C, et al: High All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease in Primary Care: Five-Year Results of the getabi Study. Circulation 2007.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, et al: 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients with Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary. Vasc Med 2017, doi: 10.1177/1358863X17701592.

- Hirsch, AT et al: Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA 2001, doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Angiologie – Gesellschaft für Gefässmedizin: S3-Leitline zur Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der peripheren arteriellen Verschlusskrankheit. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/065-003l_S3_PAVK_periphere_arterielle_Verschlusskrankheit_2020-05.pdf.

- Jeanneret-Gris C: Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD). The most important differential diagnosis in leg pain. Phlebology 2014, doi: 10.12687/phleb2241-6-2014.

- Nordanstig J. et al: Walking performance and health-related quality of life after surgical or endovascular invasive versus non-invasive treatment for intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.02.019. Epub 2011 Mar 11.

- Nicolai SP, et al: Multicenter randomized clinical trial of supervised exercise therapy with or without feedback versus walking advice for intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.022. Epub 2010 May 15.

- Steffel J, et al: Swiss expert report on the practical use of rivaroxaban 2.5 mg 2× daily plus ASA for the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or peripheral arterial disease. https://dreicast.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/3_Schweizer-Experten-Bericht_Xarelto-vascular.pdf.

- Gencer B, et al: Expected impact of applying new 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines criteria on the recommended lipid target achievement after acute coronary syndromes. Atherosclerosis 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.049.

- Wright JT Jr, et al: A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. SPRINT research group. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(22): 2103-2116.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(12): 26-27